Notable Sandwiches #105: Lampredotto

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the feature in which my editor, David Swanson, and I track our prey through the underbrush that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, straight from Florence: the Lampredotto.

One of the great measures of what a human being can be is a capacity for wonder. I really do believe this. I’m always finding pockets of childlike naiveté in myself that have somehow survived the rigors of adulthood, and one of them is my belief that the ability to take a deep breath and marvel in total delight at some hitherto unknown beauty, or some wild and complex thing, is a capacity to preserve, one that must be protected.

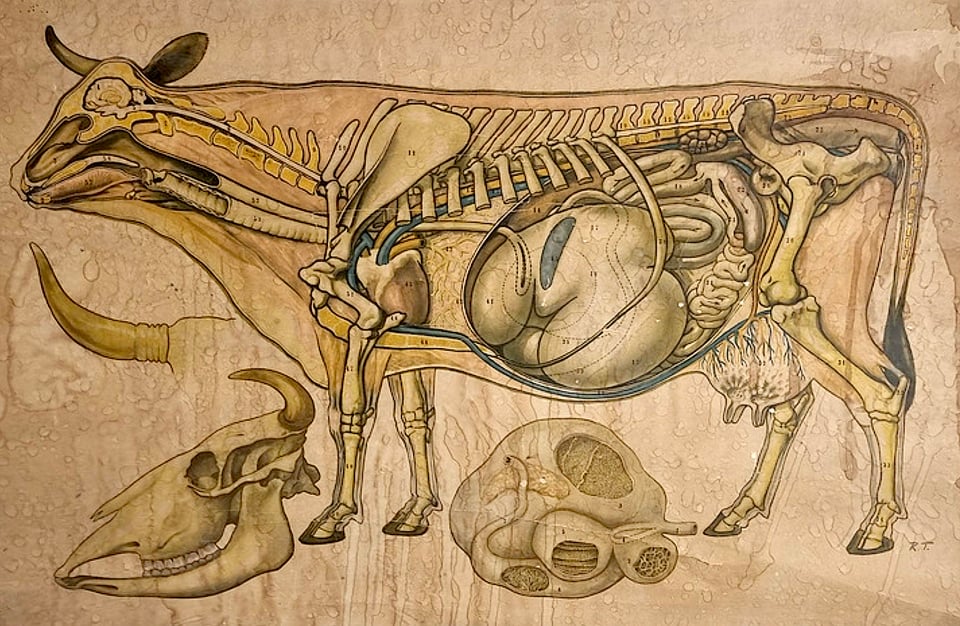

Such was my feeling when, pursuing the origins of this sandwich, I found myself studying deeply and for the first time the stomachs of ruminants—cattle in particular.

Hamlet said what a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, and he had his own designs for expressing that wonder. But there are other faculties we have, all the things that make cerebration possible, and they, too, are worthy of wonder. They are things that make for the infinite faculty, the angelic action, and the apprehension that Shakespeare lauds. They are digestion, and respiration, and renal function, and cellular regeneration—all the things that go on while we are otherwise occupied with our sour little greeds and noble pursuits alike. If they break, we break. Any illusion to the contrary is quickly dispelled by pain, by slowness, by symptoms as myriad as the systems that sustain us. The true miracle of man is not so much his noble reason, but the delicate, complex balance of chemicals and flesh that allow us the vivid luxury of thought.

The Florentine sandwich lampredotto forces one deep into consideration of chemicals and flesh: its chief ingredient, slow-cooked in vegetable broth, is the abomasum, the fourth stomach of a cow or ox. (Trippi, another Florentine specialty—dated, like the lampredotto, to the Renaissance-era masses of Florentine poor forced to eat the cheapest cuts of meat, and making delicacies of them—is made from the first stomach). The attention and elaborate structure our own bodies devote to thinking are, in ruminants, directed toward the complicated process of digestion. Eating grass is very complicated: so much fiber to break down, rigid cellulose to unravel into nutrition. (And grass with its rhizomes and its apical and intercalary meristems, its thousands of species—is a wonder all its own). The abundance of grasses renders such a complex system of digestion worthwhile: for cattle much of the whole earth is covered with a tender, edible skin.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Four stomachs! Each with its own role in the complex digestive dance, the chemical-factory, full of methane and potassium and acid, that turns grass into flesh that we, in turn, consume. It starts with the rumen, the first stomach, a vast holding-vat for food, with a capacity, in large cows, of up to 25 gallons of undigested matter; stomach two is the reticulum, a pouch near the heart into which heavy food drops. The third stomach is the omasum, “a globe-shaped structure containing leaves of tissue (like pages in a book),” which absorbs the water from the feed; “digesta” (digested matter) found within the omasum is drier than elsewhere, soaked into the folios of flesh. Finally we arrive at our lampredotto in situ, the abomasum: it is called the “true stomach” because within it are contained the digestive acids that break down the grass at last. In the abomasum, rennet—the chemical ubiquitous in cheesemaking, separating the curds from the whey—breaks down proteins, as does hydrochloric acid and pepsin and pancreatic lipase.

A cow hardly chews when it first crops grass; about a third of a cow’s day is spent in the process of rumination, named for the rumen, as the organic material is pushed from the reticulum back into the mouth and masticated again, and the digestive cycle continues its recursive course. Eructation—belching—is a key part of this process, as is the continual re-chewing and re-swallowing of plant matter.

From this complexity a minor miracle occurs: no other omnivore or carnivore can do what a cow does—turn tough stems and seed coats and dried hay into food, separating it into its constituent components, running it down through this four-chambered marvel, and filtering it through to the large and small intestines that both case sausages and make chitlins and, in live cows, complete the process of digestion. “On average, cattle take from 25,000 to more than 40,000 prehensile bites to harvest forage while grazing each day,” according to the Mississippi State University Extension. “They typically spend more than one-third of their time grazing, one-third of their time ruminating (cud chewing), and slightly less than one-third of their time idling where they are, neither grazing nor ruminating.” (This sounds idyllic, to me.)

It’s not a coincidence that “rumination,” in humans, is a metaphoric transformation of the process of cud-chewing: it means thinking too hard about something, obsessing, thinking in circles around it, the gaseous process of worry. Our omnivorous bodies lack four-chambered stomachs; we cannot digest grasses or seeds or hulls without the application of fire and time. Our digestive systems are paltry compared to cattle; their thought processes are, in turn, rudimentary compared to ours. Hence—and here I elide much evolution and much violence—the situation in which I am writing about eating their stomachs.

Tripe—the collective term for the edible stomach lining of cattle, rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum alike—is eaten everywhere humans eat cows, from French Andouille tripe-and-wine sausage to Slovenian vampi (tripe stew, simmered with paprika). Everywhere, human compensation for our limited digestive processes is in evidence; tripe must be approached as the tough strange tissue it is, cleaned and soaked and baked at length. The great food writer MFK Fisher, in her essay “The Trouble with Tripe,” rhapsodizes about the twelve-hour-baked “sealed casseroles of tripes à la mode de Caen véritable,” which “were as good as they had ever been some decades or centuries ago on my private calendar. They hissed and sizzled with delicate authority.”

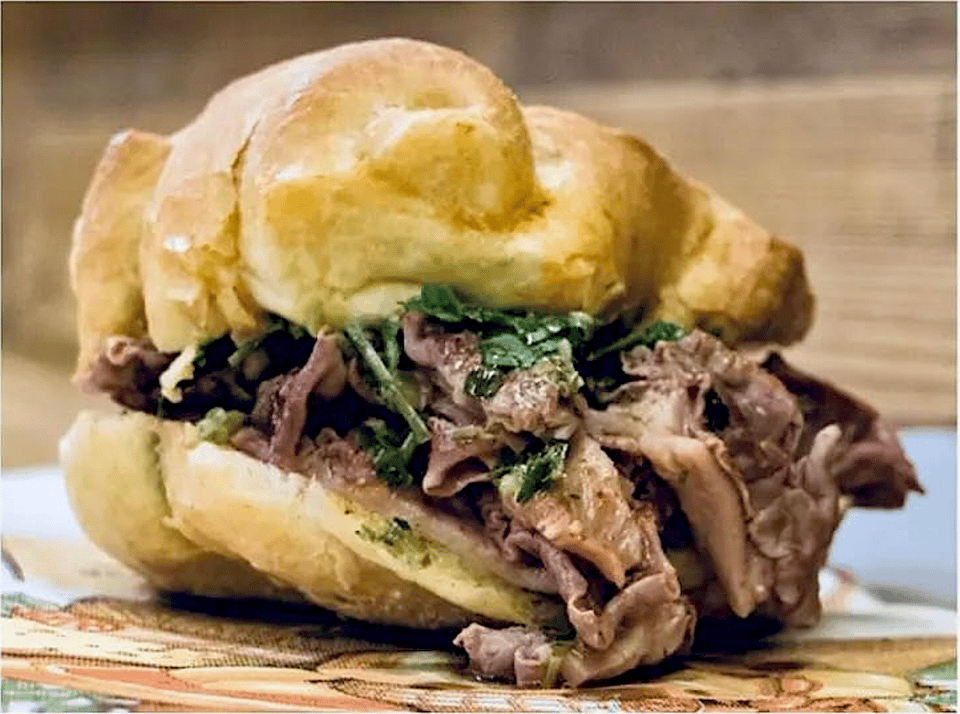

In Florence, the lampredotto sandwich is served between slices of broth-dipped bread, topped with a bright sauce of parsley, garlic and anchovy. The very name of the lampredotto, considered one of the oldest dishes in Tuscan cuisine, is a class-inflected irony: a delicacy for the rich in Italy, among other places, was the lamprey, lampreda in Italian; by contrast, the working and middle classes were restricted to offal, and the lampredotto is named for its superficial resemblance to more exotic fare.

It is treasured in a city whose ancient streets recall the rise and fall of empires and city-states, benevolent oligarchs and avaricious banditti, exceptional craftsmen and officious condottieri, their gonfalons aflutter. It is conceivable that Brunelleschi, en route to designing the cathedral of Florence, might have seen a lampredotto stand, or sampled one; likewise Donatello, Botticelli, Michelangelo, on days when they were broke (but not Leonardo; he was the rare renaissance vegetarian). From the rumination of cattle comes the rumination of the artist on his subject, the dome of the cathedral, the hand of the woman resting on her warm cheek; grass feeds on light, cattle feed on grass, we feed on cattle, and create in our capacious chambered minds a way to capture light again, on the canvas, on the page. This sequence—sun, plant, mouth, stomach, meat, hand, light—is a subject for wonder. Let the capacity for it seep back into you, let it soak in like a good broth, hold it high and sacred as a cathedral dome, humble as a pot of lampredotto on the flame.

-

A delight, as always.

-

I have no idea why my comment has replicated in this unsettling fashion.

-

Perhaps the comment section is mechanically masticating your comment!?

I, too, am delighted!

What incredible research, original analysis, and lovely prose. Another masterpiece by La Lavin.

Add a comment: