Notable Sandwiches #103: Kottenbutter

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the series where I drag my long-suffering editor David Swanson through the bizarro, shifting sands of Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches, in alphabetical order. This week, a workingman’s lunch from rural Germany: the Kottenbutter.

I’m just gonna say it: rural Germany kind of freaks me out. I mean, there are tons of woodlands and handy crags to hide bodies, and half the villages’ names literally start with “Bad.” On the one hand, I know that I’m being totally unfair to those who sensibly want to live by green pastureland, mature forest and alongside the banks of the many tributaries of the Rhine. On the other, I’ve read the Brothers Grimm. I love lakes, forests and rivers; I feel alive with the lap of water around my big buoyant body; but sometimes, in my imagination, the countryside feels more Wicker Man than All Creatures Great and Small. Especially in Germany. Especially when the region in question is most famous for making knives. (I’m trying really hard to fight my innate, Holocaust-survivor-granddaughter prejudice on this, guys. Bear with me.)

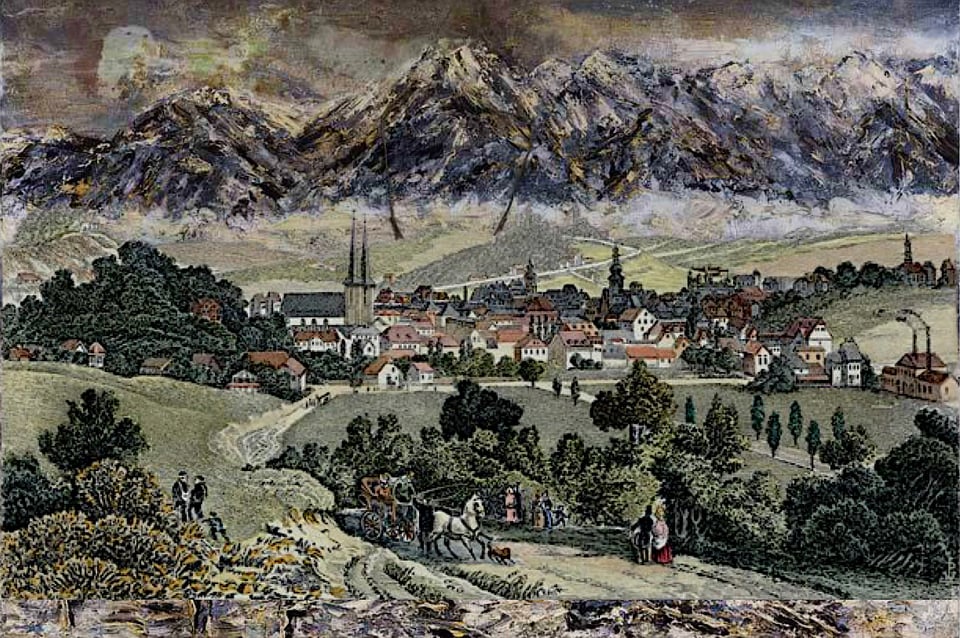

All of this is a roundabout way to get to the meat of the sandwich in this column, the Kottenbutter, a regional specialty of the Bergisches Land, a farmhouse-and-meadow region of low mountains between the Rhine and the Ruhr. Specifically, the sandwich—buttered brown bread filled with regional smoked-pork or pork-and-horsemeat sausage, onion, and spicy mustard—is best known in the three cities that form the Bergisches Land Triangle, Solingen, Wuppertal and Remscheid. Wuppertal is the largest of the three, with preserved sites relating to its long and storied history as a bastion of the working class; Friedrich Engels, coauthor of the Communist Manifesto, was born in Wuppertal, and his ideology was influenced by the textile mills and blacksmith shops that then lined the streets, teeming with the proletariat. (Speaking of me being kind of a jerk in the paragraph above, this region isn’t even that rural—Wuppertal has over 300,000 residents, Solingen over 100,000).

It was blacksmithing that made the Bergisches Land famous—the region has a history of specialized knife-making that dates back to before the Middle Ages—and Solingen, in particular, is still the knife-making capital of Germany (check out these sweet blades for corroboration). In the 14th century Solingen earned its extremely awesome nickname, “The City of Blades,” as blacksmiths and knife-makers (also known as cutlers) settled in the region en masse. One company, WKC Solingen, claims to have operated continuously since 1573, and offers over one thousand sword models, with shipping to 130 different countries.

The Kottenbutter served as a crucial staple for these craftsmen. Before the twentieth century, knife-making and blade-grinding in Solingen was handled, in large part, by independent two-man teams, working as subcontractors for big companies. According to a backgrounder on the Kottenbutter provided by Naturpark Bergisches Land, the water-powered workshops these cutlers worked from were known as “kotten,” a German word meaning “little cottage.” The work was both complex and arduous, involving lots of complicated steps, grindstone work, and immense time pressure from the large companies the workers served. As such, the cutlers were supported by “Liewerfrauen”—women who supplemented the workers’ home businesses by delivering lunches and taking away finished knives in trademark large wicker baskets.

As often as not, the lunch in question—nourishing, easy to eat, and quickly demolished—were Kottenbutter sandwiches, the bread and meat handily sliced by the incredibly large supply of knives on hand. (There’s also—I have to mention this—a quite nice-looking sword called the “Solingen” on offer from one of my favorite sword sites, Albion Swords, which is a replica of a Solingen-forged sword on display at the Deutsches Klingenmuseum in Solingen. It even looks sharp. And it’s not often that a single city offers both a sword and a sandwich.)

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Most of the towns in Bergisches Land were bombed to hell and back by the Allies during World War II, due in part to their status as manufacturing centers—Wuppertal, in particular, fabricated adhesives used in German aircraft during the war—and most of the industrial heritage of knife-making was destroyed in the process. One of the largest manufacturers in Solingen, Alcoso, was founded by the German Jew Alexander Coppel in 1821, and spent the subsequent century manufacturing items from cutlery to scissors to steel tubes to blades. In 1936, it was “Aryanized” by the Nazi government, stolen from its Jewish proprietors. Its current manifestation still boasts an 1821 founding date and the initials of its founder: Alcoso is an acronym for Alexander Coppel Solingen.

A few relics of Solingen’s prewar knife history remain, such as the Wipperkotten, on the banks of the Wupper river, the last remaining original Solingen grinding mill. The Balkhauser Kotten, a museum with a wildly impressive array of grindstones, mill wheels and other blade-making equipment, is also in Solingen, rebuilt in the eighteenth-century half-timbered style, and offering an array of blade-sharpening demonstrations and workshops. These are, however, for the benefit of tourists alone: after the war and economic collapse of Germany, the home-based, subcontracted knife-making system that made Solingen famous—and the concomitant system of Liewerfrauen who brought them Kottenbutter sandwiches—was dead and gone.

Since then, Solingen has acquired a certain infamy. In 1993, an arson attack by neo-Nazis against an apartment building with a large population of Turkish immigrants killed five women from the same Turkish family and injured twenty-one others, in an incident that set off demonstrations across Germany. In March of this year, another arson attack, also against immigrants of Turkish origin, killed four, although the perpetrators have not yet been apprehended. Industrial decay and violence against immigrants go hand in hand, and Solingen’s sharp and gleaming past is a dark contrast to a present marred by racist violence.

None of this, of course, can be blamed on the Kottenbutter, a sandwich innocent of any violence, as sandwiches tend to be. Nor is the industry of knife-making—the hard, precise work of creating a good blade, the beautiful tang of a sharp sword, the runnel and the pommel, the spark and the quench of the forge. The smithies and mills that gave rise to Engels were once here; the Wupper runs wide and blue and beautiful under the trees in Wuppertal, Germany’s greenest city. A river, constantly renewing, is always forgetting itself, even as it runs through the same bed; a city rebuilt after a bombing is not the same city precisely. But the undercurrent of menace along the Rhine remains, rancid as a spoiled onion in a Kottenbutter. Luckily, no region is better equipped with the tools to excise it.

Add a comment: