Notable Sandwiches #129: Pan Bagnat

Welcome back to Notable Sandwiches, the movable-feast where my editor David Swanson and I pull up a chair at the strange table that is Wikipedia’s List of Notable Sandwiches and invite you to dig in. This week, a personal favorite: the pan bagnat.

But first, some news: There is going to be a Book of Notable Sandwiches! I’ve sold the idea of collecting these essays, and adding to them, and not incidentally finishing the alphabet, and making a book of the whole thing, to Simon & Schuster. I couldn’t be happier to work on a project that’s already brought me such joy, and the collection may differ substantially from the already-published essays, but it started here. It started because of your faith in me and your support, and I couldn’t be more grateful. Today’s essay is deeply personal, part of the story of just how much you can write when you set out to write about a sandwich. And there’s so much more to come. I can’t wait to share this book with you all.

This is a love story.

You’re nineteen, and you come from a religious family. You’re doing your best to eggshell your way out of the faith, pecking at that nacreous hold of laws and customs with your soft little beak of new freedom. You’re just out of a year’s seminary study, a year of Talmud and commentary; just out of eighteen years of religious education, eighteen years in a town so full of piety your mother got texts if you wore a tank top on the street; you are meeting people, for the very first time in your life, with Christian names, with names of all ethnicities, in fact. You want to dress like a secular girl, the secular girl you are going to be for the rest of your life, but you don’t know how yet.

Only a month into your secular education you meet a boy—he’s still a boy then, just as you’re still a girl—with the most luminous dark eyes you’ve ever seen, and a lush mess of dark curls. He has no notion of how lovely he is. Those eyes. He, too, came from a very religious family. He, too, is in a certain process of discarding it. You are in the same dorm because it has a Sabbath entrance you can open with a manual key. This is the last person you want to feel stirring feelings for. Much of a muchness with all your life before, when you want to break that chain so badly. And yet… He’s a foot taller than you, and broad with it, and those dark curls—and he listens to all the things you say, and lights up when you come into a room.

It’s only October; you are playing a ridiculous prank on a friend. This is your friend Paul—who is also the first person you’ve ever met named Paul—who is tiny and towheaded, came to college ridiculously early, has Harry Potter spectacles, and you’ve decided to play a series of very gentle pranks on him, declaring that he is the Prince of the Woodlands, has come into his inheritance, and all the squirrels and wood-animals of New England are his to command. You’ve enlisted the help of new friends with calligraphy skills to write the formal letters. For this prank, you and the boy are gathering acorns in an absurdly green field. You’ve bought a gaudy dollar-store ring with a purple gem to bury in the bottom of the box.

The pranks have been going on for a week and are very silly, and probably ought to stop with a confession that you just thought it was funny, but here you are gathering acorns. Maybe your hands touch, maybe there’s something intimate about putting those ripe-to-bursting glistening brown seeds in the little cardboard box. He musters his courage, says he’d like to spend time with you. There’s something in the air along with the burnt-pitch-and-leaf smell of autumn, the light is golden-hour good, his lovely face betrays some anxiety, and of course you say yes. You hold his hand walking between the lemon-yellow and mauve houses, walking on good old New England brick.

Somehow it’s four years later and you’re still with him; you’re a woman now, more or less, he’s a man now, more or less, and there’s been a great deal of philosophy and languages (you) and biochemistry (him) learned, and other learning, too. How to sum up four years? He held you when you had your first night terror. When you’re ill and in the hospital, he’s by your side, every minute. You made him a scavenger hunt for your anniversary, and it ended with the two of you kissing in your favorite, climbable tree. He shows you movies you never knew existed. You drink hot chocolate from the good shop that melts real chocolate into it.

And there are less-good parts, many less-good parts, because you’re not formed yet, you’re angry and amorphous and figuring out so much, and you didn’t expect to wind up with someone whose background rhymes so closely with yours, let alone so quickly, or for so long. And whom your parents manifestly approve of: he’s going to be a doctor, after all. You make mistakes. He forgives them. You break up with him. He takes you back. You’re always sick; you’re always wrong. He always forgives you. You can’t figure out why you keep acting so wrong, when he’s steady, stolid, kind, and so smart, and his eyes still astonish you. You don’t know why you’re a mess, or why there aren’t sufficiently descriptive terms for how beautiful brown eyes can be, how changeable they are, teak, mahogany, shades of blondwood in the right bright light. Why you don’t love this perfect man as he deserves.

A year later he visits you, in Kyiv, where you’ve gone on a grant after graduating. This is before the revolution and the war, and it’s a big bustling city with the most astonishing churches, with a hundred-foot statue of the Motherland rearing up for war. It’s November; he asks you about the locks on a certain bridge people put up for love; you buy a lock. He takes out a necklace, studded with diamonds, shaped like a key. He asks you to marry him, with that little nervous tremor that melts you. You’re in a red coat, your cheeks flushed with cold, and you look at this man who’s come thousands of miles for you, and you say yes, yes, yes, yes, and let him clasp the chain around your neck.

You marry in front of a whole congregation of friends, family, family friends. It’s a huge event, in a wedding hall. You’re the first of all your college friends to be wed. (Most of them won’t marry for a decade or longer, still.) You look like a cruise-ship in your wedding dress, big, white, and carrying many passengers: all the selves inside you, the one that’s delighted to be taking such a well-trodden path, the one expected of you, the one that pleases your families; the one that loves him desperately, this boy-man who looks at you with a fondness so intense it makes you buckle at the knees, or feel ashamed, because how could anyone love you while they know you as well as he does? (Later you will look at him smiling so hard in his wedding suit, so happy in all the photos it looks like light crept under his skin, and you will cry.) And a part of you that you haven’t acknowledged, deep under the wedding corset, screaming that this is too early, this isn’t right, you’ve never been with anyone else really, you never got to kick your feet out and be wild, you’re too young, you’re terrified, and you are going to mess this up burn this down because you’re not ready not ready at all—But you take his ring in solemnity under the chuppah, and he breaks the glass.

And there is a little time, after. He’s going to med school next year. You’re writing for pennies. He’s working, making good money with better-than-decent hours. You live in a beautiful apartment in a beautiful Brooklyn neighborhood. And there’s this store a few blocks away called the Mermaid’s Garden.

It’s an absurd little place. Bougie beyond bougie. The Mermaid’s Garden isn’t a symptom of gentrification; it’s a signal that this place has been so gentrified there ought to be baronets popping out of the bushes, lords on every corner. The place offers absurd things for sale: a lump of monkfish liver for forty dollars, on a bed of ice. A single huge scallop. A postage-stamp-sized lump of sea bass, its coal-black skin clinging to that rich flesh. Tiny containers of sauces. Twee books, related to fish.

They also offer pan-bagnat: a sandwich of the South of France, of Nice and Provence, once cheap fare for workmen (not cheap here, but just now you can afford it); French bread, wetted with water (now the juice of fresh tomatoes, and the bread doesn’t have to be stale). Inside, perfect slices of hard-boiled egg—the yolk sun-yellow—capers, olives, lemon, tomatoes, and decadent oil-drenched tuna, flaky and fine, blending with the lemon into a sheer perfection. Coming from such pristine environs, it’s a surprise. It’s a whole loaf, pressed into submission to contain its mass of contents. It is the perfect sandwich to take into the park, one hand on the sandwich, one hand on his warm hand, to devour together.

To love and be loved. You don’t have it every day. You shouldn’t court perfection every day. You have it—say—once a month, or a little less. It’s perfect every time, and at this distance, to your memory, it was warm every time you sat on the grass and leaned on each other, and his eyes were still fond and deep and dark and gentle, and his arm around your shoulders, when all the crumbs are brushed off your dress and all you have to do is sit together sated, is so warm, so upholding, and life tastes like capers and lemons and good bread. He’s the good bread of your life: perfect in himself, and holding all the acid colorful restive bits of you together, and together you’re a pan-bagnat of a whole, a good thing, a necessary thing.

And then.

You are not a good wife. You are less and less of a good wife. You are a terrible wife in a med-school dorm with a two-hour commute. The other good Orthodox couples have babies already. The elevators never work. He takes you to the anatomy lab and you run out feeling faint, formaldehyde clinging to your nostrils. You live too high up and too far and are far too alone, and he’s busy becoming a doctor. There are good sandwiches in this neighborhood—excellent, in fact—but no pan-bagnat, no Prospect Park, no time to sit in the sun. The parts of you held tight under that wedding corset are breaking out.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

He’s studying to be Dr. Jekyll. You’re apprenticing as Mr. Hyde, and you can’t stop. You’re cruel and self-indulgent and unfair. The more he keeps you together, sets you right, the worse you act, and the more you fall apart. Oh, you act badly, badly, badly. And he weeps when, finally, long after he should have, so much longer than he should have waited, he tells you to leave. And you beg, because part of you really thought you couldn’t find the limits of his forbearance. But you go.

Your divorce is laughably simple. The marriage hardly lasted two years. Neither of you owns anything worth noting. You take the pitcher shaped like an elephant he hated and you insisted belonged on the wedding registry. You take too many of the dishes. You leave too many of your books. You get divorced in front of a rabbinical court, which demands nothing of you but silence as you’re renounced, just as the marriage required nothing but silence as you were claimed. You’re supposed to walk backwards out of the room. You moonwalk. And then you cry, in the adjoining room, like you’re the first person who invented crying. The first person to feel regret or heartbreak. How could anyone feel these things and not fly apart? How can people walk down the streets of this city and have felt this, and lived?

Finally you have time to have the things you thought you wanted. The reckless and stupid nights. The ill-considered passions. Experience with people of different backgrounds, of different names and genders. You have as much time to be stupid as you like. But you’re afraid you’ve been stupid enough for a lifetime. You’re twenty-six, and you’ve picked out a spot for weeping on the stairs at work. You weep a lot. You linger with cruel men longer than you should. You learn to live without him, in time. Not well. Or elegantly. But you do. For a long time it feels like your skin is raw with humiliation. Or that divorce is a brand on your skin. But it isn’t. Your years with him are like a dollar coin in your fingers, smooth and lovely and outmoded, surely unnecessary, surely better spent than kept. It’s stale bread. It’s crumbs. It’s over.

But something more than a year later you ask for your books, because you miss them. Just the books, mind you. And he drives you back to his med-school dorm, and you take them back.

And then he asks you to dinner.

And you go.

For years it’s sub rosa. Something between other entanglements. A floor over the abyss of loneliness. Nothing that means much. Except his eyes are still perfect. And you keep returning. You can’t have him back, not fully, not after all you’ve done to him. But still: No matter who else flits through your life, with what unlikely constellation of tattoos or what alluring hair or what sweet words they say. There is a man you want to keep returning to. The one you gathered acorns with. The one whose heart you broke. The one who tolerates your company. Who shows you the works of Akira Kurosawa, and makes you laugh. You’ve been with men and women and people who are neither but this is the one you keep coming back to. Seven years together, two years apart, and more years in this in-between, arms-length state of loving. No promises. No chuppah. You tried that. It didn’t work.

And then there comes a time when he needs you. More than you ever needed him, for all that you made him run around after you to prove some point that seems incomprehensible and cruel to you now. He really needs you, for a little while. And when he does, you open your home to him, your life to him, all of it. You delete the dating apps from your phone. You stop having one-night stands (frankly with some relief). You’ve had enough empty nights for a lifetime. You kicked over the traces and you ran rampant and some of the demons that drove you are gone, worn down by experience. You faced the worst crisis of your life without him. And he needs you now, and you are there.

And you want to always be there.

This time you ask him to go steady. And he hesitates before he says yes. But he does. And there’s an electric fizz in your step.

Both of you are centuries older than the people you were when you met. Different than the people in the wedding photos. More ready to compromise. More ready to forgive. More ready to find out why you feel what you feel. Slower and more temperate.

Sometime recently in a cab after you’ve done something forgivably stupid, you say, You’re going to leave me.

And he says, Like I’ve done such a good job kicking you out of my life.

And even as an exhausted resident he summons up that smile for you, like summer but better because summer in this city is awful, but that smile has all the warmth and light you need.

And someday you’ll go back to the Mermaid’s Garden, the silliest shop in the world. You’ll get that pan bagnat. You’ll sit under the trees. The sun will touch your face like his hand: warm and reassuring and necessary.

It’s the perfect sandwich. You’re not perfect yet. Now you know you’ll never be. But the dark-eyed boy you loved is now the man you love, so much it has elasticated your heart, filled it beyond capacity. You don’t need to be perfect to taste a perfect thing. Even you, sinful old you with your maundering floundering path back to the place you started from, can have lemons and capers, tomatoes and sunshine, and this man, with his impossible forgiving heart, his pale shoulders and dark curls, he can love you back.

-

You are such a wonderful writer. This is heartbreaking and beautiful.

-

Beautiful beautiful beautiful! So very well thought and written. And congratulations on the book!!!

-

That may be the most wonderful love story I've ever read. Thank you Talia.

-

wi

-

Beautiful! I am excited about the book: congratulations! And so glad that I follow you and get to read exquisite pieces like this!

-

Gorgeous. Thank you.

And, congratulations! I look forward to reading the version of these essays contained in your book.

-

Wow, that's well-written!

-

Thank you for having lived the life and telling the world about the experience which, thirty years on, I still cannot tell about mine. You have set a standard for us all. May we all work on it.

-

Holy buckets, such beautiful writing! (sigh) Thanks for that.

-

I could not love or need this story more. Please finish the sandwich book, and then get on the novel/screenplay of this blissful moment in our messed up world. So happy for you and your beautiful brown eyed boy.

-

I love this story (and not only because I also met a boy one month after leaving home, played pranks with him on a friend named Paul, and can’t quit him [redacted] years later). Very excited for the book.

-

Such writing! Congratulations on the book deal (which I absolutely cannot wait for), and for being a beautiful person. You deserve your brown eyed boy.

-

'You all' seems uncomfortable. Maybe it is time to embrace "y'all". I have learned to do it even though as a Canadian I instinctively avoid USisms.

-

Perhaps some of your finest work, and that's saying something. What a beautiful gift, to have someone prove to us that our foibles, our human failings, and our inevitable stupidities are indeed forgivable.

Congratulations on the book, which I'm sure I'm not alone in saying I cannot wait to pre-order!

-

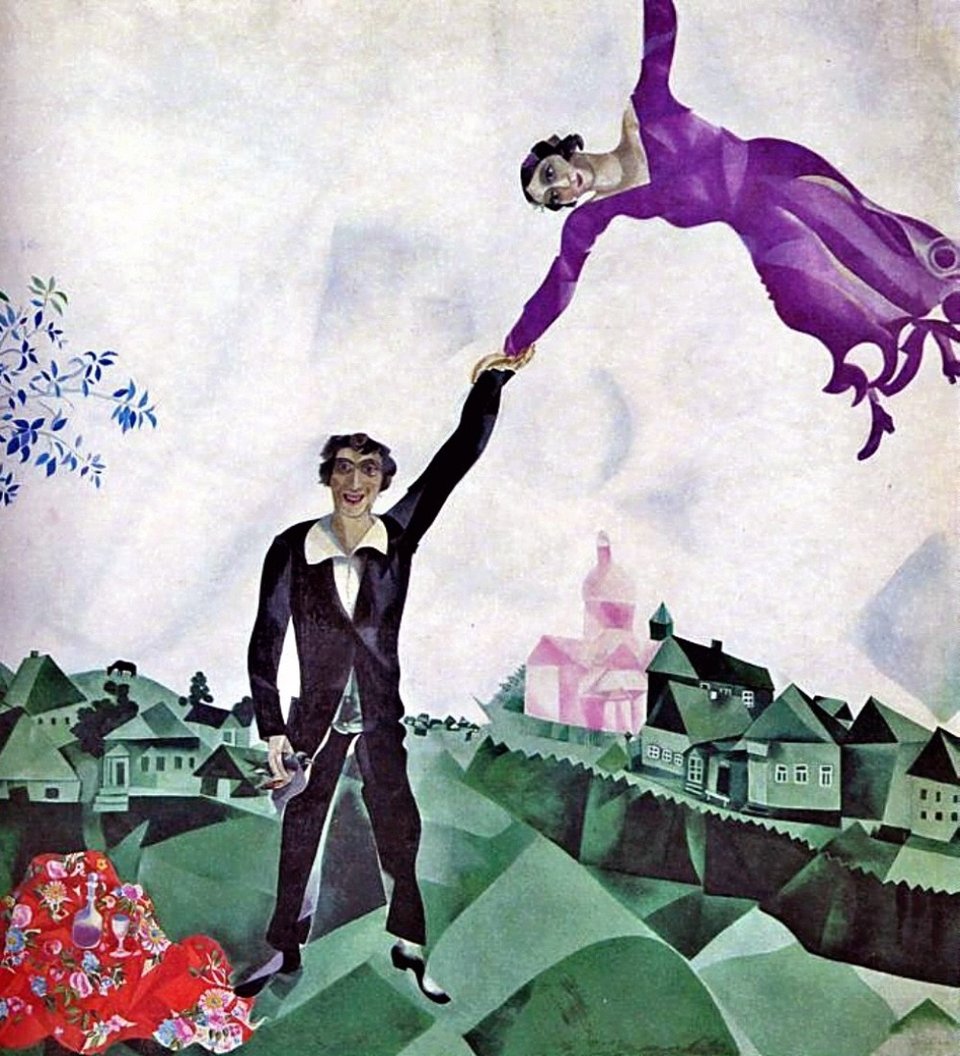

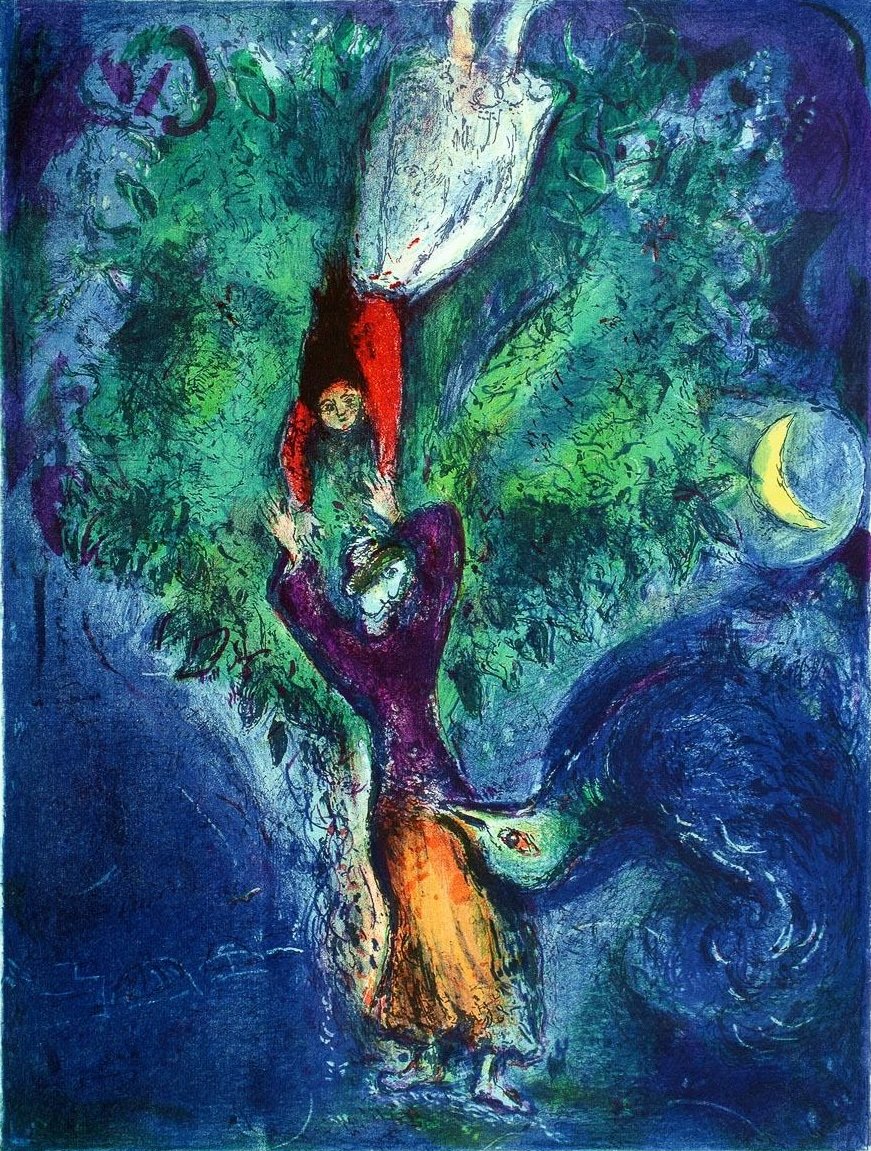

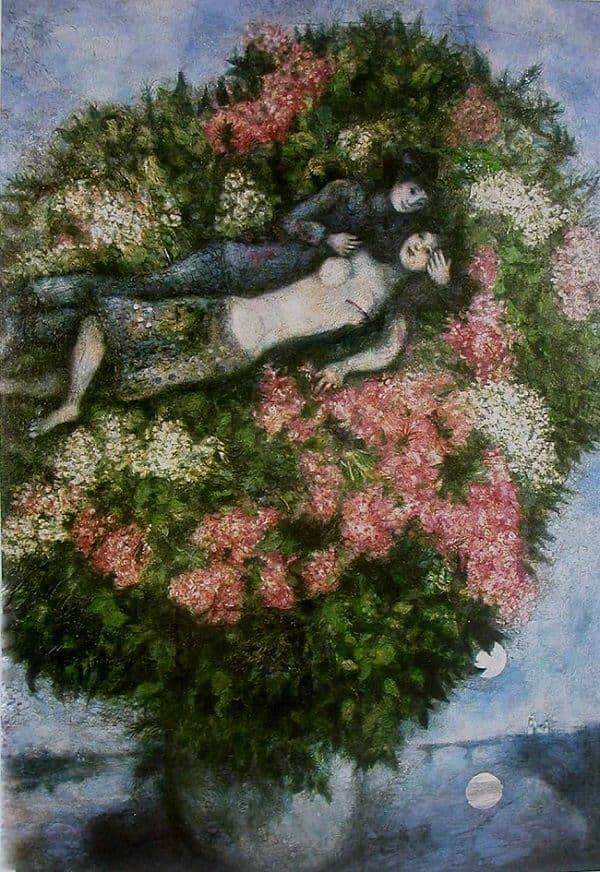

Wowowow . . . this is so beautiful. I am weeping with understanding at being "that girl" myself. And pairing it with Chagall is perfect. I cannot wait for your book.

-

thank you for writing this. it made me cry a little into my breakfast burrito and orange juice as i think of a girl with dark eyes and warm hands that i loved in a part of my life that can't be returned to, and those memories are good and worth keeping but still make my heart cramp. i can't wait to read the sandwich book. thank you

Add a comment: