Into the Arctic

If I had to come up with a metaphor for my mind over the last few months, a wooden ship bound in pack ice would be a good one: wracked by pressures that heave and push at its hull, locked in for an unknown period of certain darkness, and outside a void of howling, hostile whiteness. It’s an analogy that suits the degree of paralysis and despair I’ve been feeling, and the concomitant inability to put pen to paper—an act that, in a less turbulent mental environment, is as natural to me as any natural function. This has been the longest creatively destitute period of my adult life, spanning two months. Into the declivity and utter emptiness where words once flowed freely a mass of inner ice insinuated itself, blank and unyielding, to the furthest horizon.

This sounds dramatic, I’m aware. But I’ve always been prone to dramatics, and, to me, a duration of two months in which I could not write was a catastrophe. Throughout this interim period I was—as suggested by the elaborateness of this metaphor—drawn to stories of Arctic calamity. Specifically, to the long, strange, tragic, and occasionally mysterious stories of explorers, sailors, and whalers who, having set out to conquer the ice, found themselves and their ships consumed by it. In this weird blank stretch of paralysis and anxiety, brought on by political cataclysm and the profound inadequacy I feel about my little words in the face of it, I keep reading true stories about men and ships and ice.

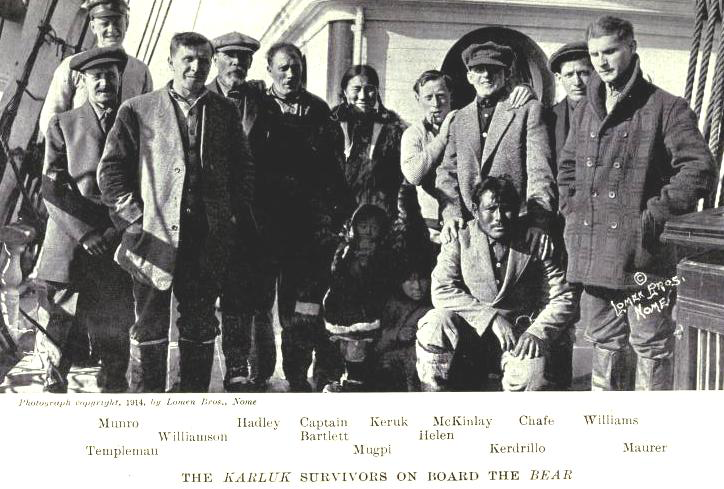

In 1880, several hundred miles northeast of Russia, ice trapped the USS Jeanette, a ship commanded by a self-taught explorer named George Washington DeLong; he died after a long and perilous journey over the shifting sea ice, southwards, to Siberia. More than three decades later, in 1913, the ice trapped the brigantine Karluk at roughly the same position, in the seas near the desolate Wrangel Island, where she drifted, like the Jeanette, until she was crushed and sank. This time its captain won through to Siberian settlements, and led an international relief mission to save the men stranded on Wrangel’s desolate shores. By the time he returned, half of them were dead.

Throughout the bizarre and pyrrhic history of the search for the Northwest Passage are the bones of many such vessels, scattered on the seafloor. From the Erebus and the Terror, the flagships of the lost 1845 Franklin Expedition which claimed 129 souls in the Canadian Arctic, archaeological divers have recovered artifacts both practical and tragic: scientific instruments, belaying pins, nails, a shoe, a spoon, a plate, a fossil, an eyeglass lens. These ships, too, were beset by ice for more than a year, immured in the floes that would swallow their inhabitants, until water won out, as it always will, over wood.

I keep returning to the image of the icebound ship to explain what’s happened to me. It embodies hubris and hope and horror. The endless night, the unsought pause, the long cold curl of the wind off the ice, which grinds out its restless consuming song. I keep turning to the news—grim, grimmer. A country devouring its most vulnerable. A country that willingly put itself in the hands of predators. That sailed into the heart of the icepack, to have all its life and goodness smashed. Then I turn back to where the ice isn’t a metaphor. I am hungry for these stories in a way I can’t fully explain, even to myself.

It’s been a strange, lurching self-education via an erratic curriculum. Often, waking up desperate to fall asleep again and sleeping with no desire for waking, the only thing I could summon up the energy to do was read, if even that. I’ve read nearly twenty books about Arctic and Antarctic exploration, plus a few related maritime disasters, and come out, among other things, knowing a great deal more about the varied textures of ice and its habits.

There are icebergs and brash ice and floe ice, growlers and bergy bits, sea ice and shore ice, pressure ridges and sastrugi, leads and polynya. Ice is not alive, but, collectively, it acts as a living thing. It will split under your feet; it will split under your sled; it will open its mouth as if it hungers for you; it will shift and weave and stun and bombard you.

I know about the progression of scurvy, the many uses of seal-sinew rope, and the causes of pemmican nephritis. I’ve looked up a portrait of Adélie Dumont d’Urville, a French explorer’s wife and the namesake of the Adélie penguin. I know about the bodies at Beechey Island. And I need to—I must—know more and more.

In the land where eternal dark and eternal sun take turns, it is, for the unaccustomed, always hard to sleep. The eyes play magnificent tricks when confronted by a superabundance of ice and sun: ice blinks, water clouds, sun dogs, parhelia, and Fata Morgana. The aurora borealis (or australis) dances in the black sky of the polar winter, and in the brief summer it’s always noon, the sun rolling like a marble around the sky without ever retreating entirely. Compasses play tricks at these latitudes too: so close to the origins of north or south, they cannot tell their direction.

These climes were uncharted, or badly charted. An island being an island versus a peninsula—difficult to tell when the sea is a field of ice and so is the land—can determine the fate of an expedition. A hunted seal can stave off scurvy for a day or a week, if you know how to find it, and how to wait at an air-hole for five hours, or six, or a day. And all the while your beautifully-outfitted ship, on which you relied so utterly—your home and your mistress, whose every inch you know so well—cannot move, and is being crushed, and is drifting slowly, so slowly, you know not to where.

There are heroes. There are blackguards. There are ordinary men struggling to survive, the elements of the self in extremis mirroring the freeze and the gale. A man repairs a leak with mashed ship’s biscuit. An Inuit seamstress chews boots to repair them. The English perform drag pageants on the ice. A man clubs a seal with a ski. They eat the sled dogs, unless they didn’t bring any, in which case they were probably doomed from the start. Men warm their frostbitten feet under each other's parkas. They find scurvy-grass, with its little white blooms, growing on a grey gravel hill, and they collect it in their bruised and tender hands. They learn to share their catch, or else kill over it. They hold each other for warmth. Even in death, they embrace their comrades. They are gentle or cruel or mad by turns, but surviving in the Arctic is a matter of cooperation as much as luck or will.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

The explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson, who wrote a book called The Friendly Arctic, abandoned his charges on two separate expeditions, resulting in the deaths of fourteen people. This place is indifferent, but you are an aberration, and on balance it would like to see you dead.

The wind can kill you. The ice can kill you. The water will kill you quick. The bears can kill you. The food you brought can kill you if improperly tinned or stored. The lack of food can kill you, too. The night can make you mad. The daylight on the snow can make you blind. If you survive you will always want to return. You will go to war to try to forget it, but you will never forget it. Part of you will always long for it.

As to the less compelling and entirely metaphorical inner ice looming over me—the longest period without writing of my adult life—the whys are complicated; chiefly the ascent of Donald Trump and his regime to power on January 20th, and the attendant, slow-and-fast mixture of abominations that have rolled out thereafter.

Since 2017 or so, I’ve been writing about the ascent of these forces—first the Internet-poisoned crypto-fascists embodied so neatly in the persons of Elon Musk and his marauding band of DOGE minions. My second book covered the legions of the Christian-right, whose gleeful and unrelenting attacks on women, trans people, and queer people are enabled by the ascent of their declared divine messenger, Trump. The dual nature of these ideologies does not preclude their cooperation, since the ultimate end goal—power, and domination, and degradation of the public good—is largely agreed upon. And both agree that no matter what else is cut to the bone, the punitive force to annihilate enemies—both enemies perceived as such by dint of identity or class, and those who muster up the courage to mount real opposition to the new regime—must and will be preserved.

I wrote about these forces as they grew. I watched them win. I am watching them winning. I feel spars inside me break and crush, and know my hull wasn’t hard as greenheart.

John Franklin’s lost Arctic expedition of 1845 was for a long time one of the world’s great mysteries. Two of the Royal Navy’s prize bomb-ships vanished with all their men, and a great larder of tinned food, and the final hope for the Northwest Passage. Theories about lead poisoning, cannibalism, and murder float around the scant documents that have resurfaced. Into the void left by the absence of diaries and letters, ghost stories—including Dan Simmons’ clumsy, misogynistic doorstop of a novel, The Terror, which posits that a monster ghost-bear ate John Franklin—rise up out of the fractious ice. It’s one of the most epic tales of hubris imaginable, and its leader embodies the futility of man pitting himself against ice.

John Franklin, emblem of Britain’s star-crossed chase for the Northwest Passage, had already been knighted for the 1818 Coppermine Expedition, which sought the Passage’s entrance overland in Canada, a fiasco raddled with death. It was a bad year, and natives called the route of his expedition “The Barren Lands” for a reason. The English fur companies serving as Canada’s de facto government were at war with each other, and did not adequately supply the mission, needing to keep their resources available for slaughter. Even so, Franklin did not turn back when he could have, even as his food ran out in treeless Arctic Canada, and eleven men died, most of starvation and two by murder.

In addition to his knighthood in the service of abject failure, Franklin was granted the sobriquet “the man who ate his boots.” Of course, he ate worse on the Coppermine Expedition. The chief dish (beyond rumored cannibalism) was a gastric disaster called tripe de roche—rock tripe—made of lichen, the most survival-adapted of all forms of life. Somehow, Franklin too survived, and went on to even greater failure.

Still, it’s a good time to think about lichen, in all its colors, in all its quiescence, in all its ability to adapt, to fire and freeze and rock and salt. It will perhaps even outlive the ice of the Arctic. When all else fails, there is tripe de roche; when all around you is failing, there is the ice to return to, the wild white waste of it, the howl and gnash of the wide, wide frozen sea. I turn my eyes to the past and the expanse of living ice. It’s a temporary lodging, but a firm one: a ship in the heart of a floe. I am letting this current take me for a while.

-

Wow. Once again I am blown away by the power of your prose. I am sorry about your dark spot, but goddamn, it's good to have you back and creating again, no pressure, of course. Thank you.

-

♥

-

This was really good. I'm glad you were able to break through the ICE and share it.

-

Very beautiful, and I was eating a delicious turkey and cheddar sandwich while reading it.

-

Breathtakingly well written, as always. And I've always loved lichen.

-

One brighter example to look to among these wastes is Fridjtof Nansen, who fucking designed a ship to be trapped in the ice, and then stranded himself amidst the floes on purpose, to try to ride the current to the pole.

It seems like absolute madness, but it was brilliantly planned and executed, adaptive to the environment and based on constant experimentation and improvement, and he and all hands lived to tell the tale.

And he then went on to fight for Norwegian independence, and be a pioneering advocate for refugees in the aftermath of the Great War, and finally a Nobel laureate. The way out is through.

-

❤️❤️❤️

-

Enjoyed reading your article. We live in a little town called Opua, in the Bay of Islands , New Zealand. Every street is named after that tragic expedition . Locals have often commented why.

-

I really identified with this article. I’ve felt very frozen and numb since the election and especially in the horrific aftermath of the inauguration. And the horrors just keep escalating. I’m having trouble finding pleasure in my usual hobbies and activities. It’s time to channel my inner lichen, I suppose.

-

This resonates, completely. and your writing is excellent.

Add a comment: