Identity Sprain

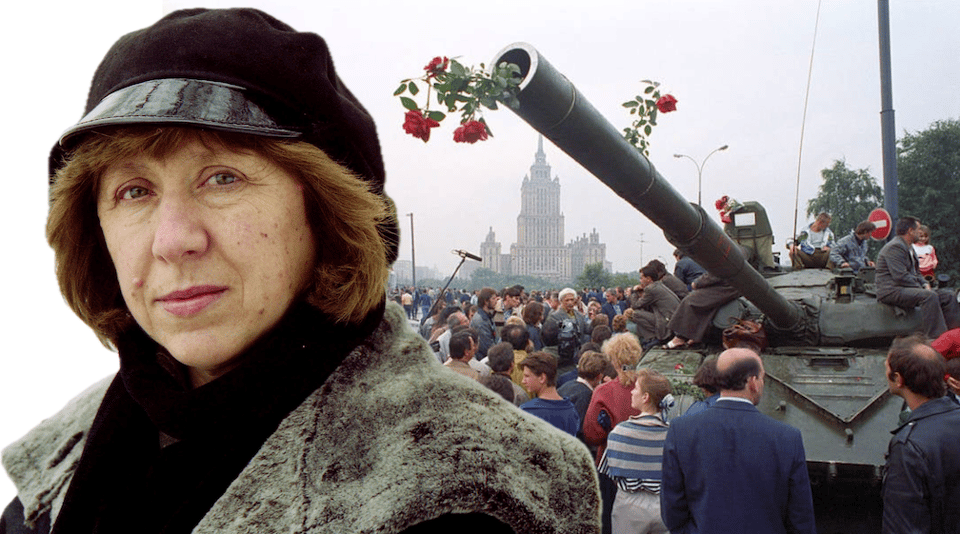

In her masterpiece Secondhand Time: The Last of the Soviets, the Nobel-Prize winning author and oral historian Svetlana Alexievich pieces together a mosaic of identities, interviewing former party apparatchiks, newly-minted millionaires, doctors, surveyors, members of the intelligentsia, and people hanging around beer kiosks, about the collapse of the Soviet Union, and what that meant for ordinary people.

Chiefly, she examines the phenomenon of the dedicated Soviet—the sovok, to use a pejorative term for someone unquestioningly invested in Bolshevik ideas—who wakes up and suddenly finds that their country does not exist, nor the ideals that upheld it. There are a range of reactions in her interviews, from wild relief to suicide. Alexievich’s stated goal in her books (which examine the Chernobyl disaster, the role of women in Russia in World War II, the Soviet war in Afghanistan, among other subjects) is to illustrate how history occurs through “this miniature expanse: one person, the individual. It’s where everything really happens.”

In history, there are few neat parallels. You cannot, for example, make ironclad predictions about the progression of fascism based on Germany in the 1930s and 1940s; there was Italian fascism too, and it looked different; you have to take into account national contexts and paradigms. The Soviet Union’s abrupt collapse in 1991—along with its iconography, the rapid breakaway of its vast territories, and its load-bearing national mythos—was the first time since World War I that an empire had dissolved so rapidly. “I still take pleasure in writing ‘USSR,’” one of Alexievich’s interlocutors tells her. “That was my country; the country I live in is not. I feel like I’m living on foreign soil.”

Part of the reason for the identity crisis that struck Soviets so hard during perestroika, the years immediately before the collapse, was the unsealing of records that had remained hidden since Stalin’s time: the truth about the purges and the gulags, the revelation of informants’ reports (one subject tells Alexievich about discovering that his “beautiful aunt Olga” had informed on his father. Her answer when he asked why: “Show me an honest person who survived Stalin’s times.”) This made the myth of a utopia even harder to sustain; that and the empty grocery-store shelves dissolved the Soviet Union, crushed the putsch that wanted to unroll all reforms.

In America we have access to all sorts of historical atrocities; while there are surely ones still hidden, the facade is sullied, has been sullied for a long time. And so, again, the parallels are imperfect. Still, reading Alexievich, this passage struck me like a bell hitting the precise point of resonance:

“On the eve of the 1917 Revolution, Alexander Grin wrote, ‘And the future seems to have stopped standing in its proper place.’ Now, a hundred years later, the future is, once again, not where it ought to be. Our time comes to us secondhand.”

We Americans, too, are living on secondhand time, watching our government mutate into an autocracy, the way gangrene forms in a wound. The evidence is everywhere: political assassinations, extrajudicial kidnappings, masked goon squads tackling opposition politicians, reckless, open, naked graft. Yet the iconography and territorial integrity of America are intact. So is its national mythos: the land of the free and the home of the brave, the nation of immigrants, the land of opportunity, equality, the American dream.

These are powerful concepts, a form of civic religion no less potent nor propagandistic than Soviet shock-worker medals or the “conquest of the harvest” ever was. American realism, all too vivid in our films and our novels and our songs, forms a genre livelier than socialist realism, if only because its creators and consumers often don’t realize that what they’re producing and consuming is propaganda. We even share the notion of having beaten the fascists as a point of national pride, of self-mythology.

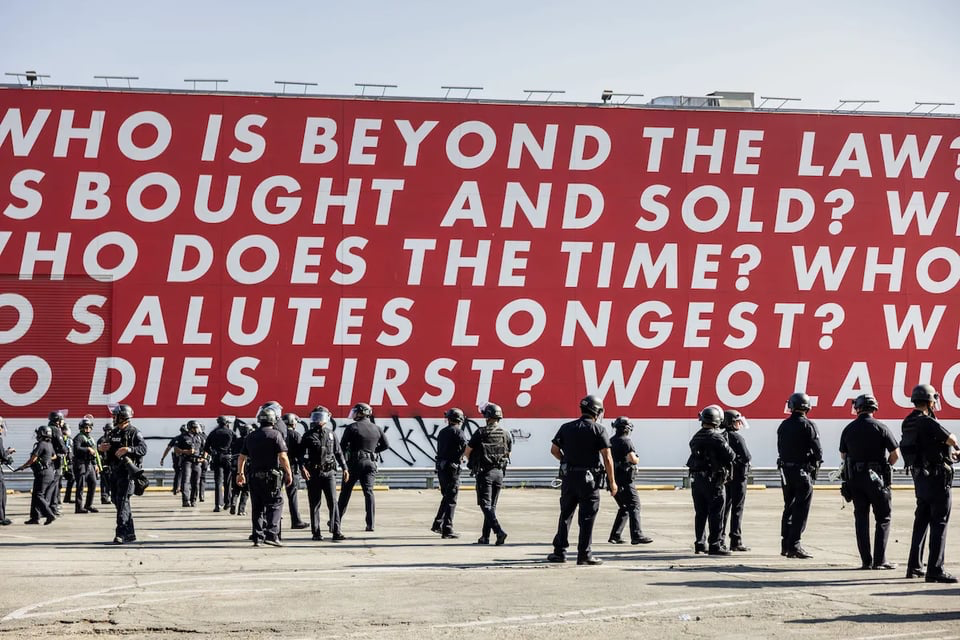

It’s telling that the latest round of resistance—relatively feeble as it has been in the face of murders and kidnappings—has been precisely on the grounds of national identity. What does it mean to be American? To be America? On Saturday, the president threw a $45 million military parade through the capital, with ranks of tanks and smiling Marines, for his birthday. This is an dictator’s fantasy: a parade of his might, a celebration of him. It was, reportedly, lackluster, though poetically convenient thunderstorms failed to materialize over the Washington skies.

At the same time, millions attended “No Kings” protests across the country, from tiny towns to our biggest metropolises. There, like post-Soviet communists bearing images of Lenin, we returned to the roots of our nation’s mythos: we cast off kings in a revolution, a tax protest that snowballed into independence for the colonies, and protesters celebrated that rebellion with painfully earnest fervor. That we had to reach so far back speaks to the strain on our national identity right now: the pain of dissonance, of the dissolution we see before our eyes.

So: Though millions voted for a self-proclaimed strongman—one who openly seeks and is currently amassing unassailable authority—millions more chose to bring the battleground to the story of the country. To recall the story of casting off autocracy, and cast it in sacred terms. Underneath the homemade signs and the smiling selfies and the clouds of tear gas slightly later on in the day, the message of the protest was this: to submit to the rule of a despot willingly, to forsake democracy, would be a violation of our national story. It would be an undoing, a collapse as thorough as the Soviet Union’s in 1991, though the shell would remain, as would the armaments.

It’s hard not to be cynical about these ideas, knowing how thoroughly they are stained. Right from the beginning and before, the original sins of slavery and indigenous slaughter weave through the sacred documents of American history; atrocity after atrocity committed on soil foreign and domestic pulses through every element of the nation’s self-image.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

The knowledge of the gulag, of the millions who died shot at Lyubyanka and Burtovo and in some anonymous Siberian field, undermined the Soviet project, because the Soviet project was always about striving towards man’s perfection and perfectibility. It is easy to roll one’s eyes at the American Dream, its cheapjack promises of little more than material satisfaction. Even our anthem is wonky and notoriously difficult to sing. It is also about bombs. The famed kickoff of our national self-determination was a cosplay against tea pricing. Our nationalism has demanded blood prices of those who could least afford it over and over, in every decade of every century since its inception.

And yet to surrender it all to the self-proclaimed “patriots” who dream of becoming secret policemen, and, in lieu of becoming them, support them with a burning ardor, would be an error, I think. There’s power in a story. There is virtue in saying not so much “This is not America,” or “This is unAmerican,” but rather: “This is not what America should be,” or “America can be better.” There is a reason to recoil at the autocrat’s parade. There is a reason to fight the masked goons. To do so in the realm of the stories we tell ourselves about who we are—who we should be, the ideas that underlie this vast knitted-together terrain—is an important battle to wage.

A country needs an idea to be great; thus the notion of equality, however little we’ve ever lived up to it, is worth preserving as an aspiration. As one of Alexievich’s interlocutors says: “Nobody even attempts to explain what country we’re living in. What is our national idea now, besides salami? What exactly are we building?” (Another responds: “Hating the underdogs, the people who haven't made millions and don't drive Mercedes… That life is nothing but pyramid schemes and promissory notes.”)

In a vacuum of higher ideals, the most venal and cruel notions will prosper. Embracing a hokey kind of civil religion and populating it with real flesh-and-blood humanism, with the zeal of those who seek to defeat a tyrant—this battleground is worth putting boots on and stepping onto. If these ideas—freedom and democracy, opportunity and equality—have rung hollow for two hundred and fifty years, that doesn’t mean they need to be hollow forever. At gunpoint, under the runner of the tank, under existential threat, millions have decided these notions are worth fighting for. That there will be no kings here, on this soil. It’s worth stepping into the ring, into the unknown future, to reset the clock on our secondhand time.

-

Thank you, Ms. Levin

I believe the President was the motivator for the particular tone of last weekend's protests. He had a few months ago trolled us with that fake Time cover showing him as a king. Seems to me that in this single case, responding to a troll turned out to be more powerful than the troll itself.

Add a comment: