How to Stay Alive and Horny Under Authoritarianism

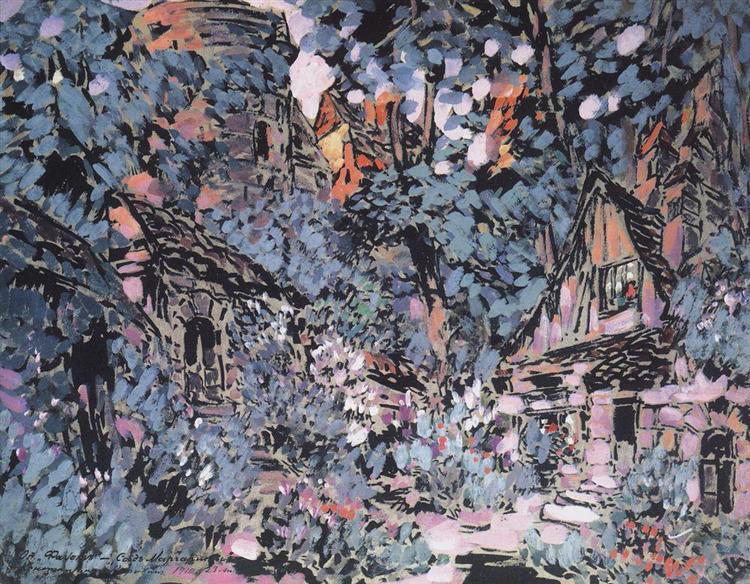

Sophia Parnok (1885-1933) was born in Taganrog, Russia—Anton Chekhov’s hometown, on the sea of Azov—two decades or so before her country exploded. Born into a hyper-educated, assimilated Jewish family, she grew up to be a hyper-educated, assimilated Russian Jew, and, by the age of twenty-one, had dedicated herself to the vocation she would spend her entire life following: writing extremely horny lesbian poetry.

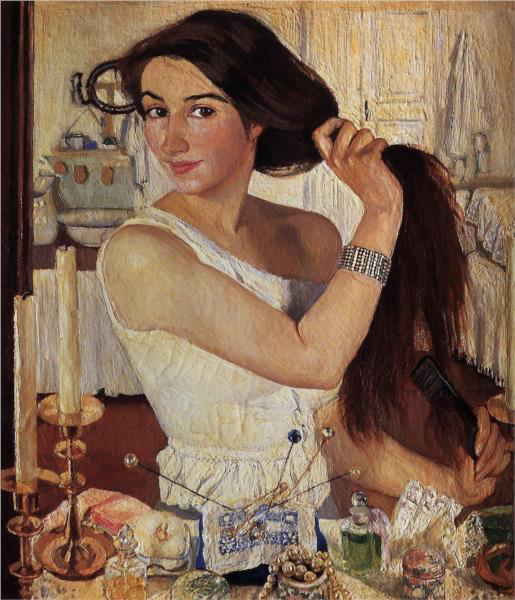

Parnok was the gayest voice of Russia’s Silver Age. She had freaky, luminous, magnificent eyes, and often wore suits. She was married to a man so briefly that, after leaving him in 1908 to take up with one of her many female lovers, she told him, “I know that my leaving you won't bring me anything good in the sense of public opinion, but I also know very well that as soon as I have my first real success, everyone who has turned their backs to me will turn again and acknowledge me with polite smiles on their faces. Therefore, I really don't care whether I see their backs or their faces."

Thanks to an extraordinarily thorough account of her various liaisons—and how they corresponded to shifts in Parnok’s modes of expression—by the scholar and translator Diana Burgin, one thing is clear: Beginning in the decades leading up to the Russian Revolution, through World War I, the Civil War, the New Economic Plan, and the rise of Stalin, Sophia Parnok was unapologetically—and unceasingly, and reverentially—horny for women.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

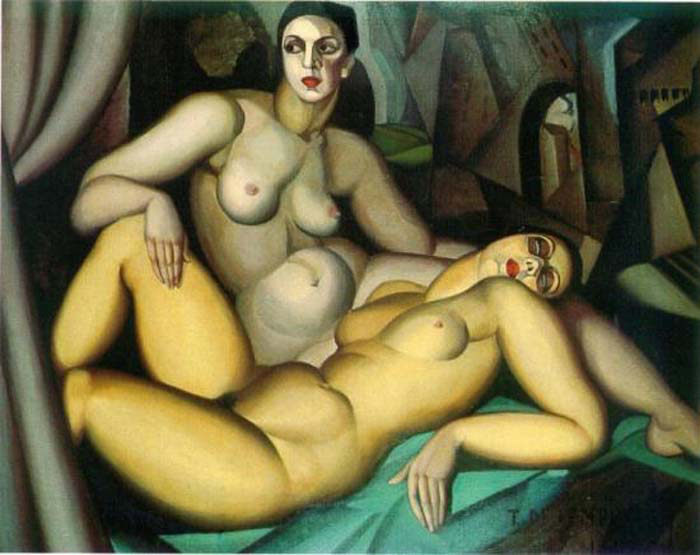

She bedded Marina Tsvetaeva, a tragic poet whose flirtations with more existential and political topics led her to exile and suicide. She dallied with minor literati, with doctors, with composers, with older women in particular (her mother died when she was very young): actresses, widows, teachers of mathematics. These were not casual encounters. Her poems thrum with a love so deep it embodies agony, ecstasy, and earthy sensuality at once. As the Russian Civil War ignited she was writing an opera, and she kept writing it as fighting reached her town. She planted a kitchen garden during the war, in Crimea, and fought the dry earth for her sustenance. But her real sustenance was love. And her love, by virtue of being outlawed, was as revolutionary as even the most ardent revolutionaries.

I am thinking of her now because she succeeded, throughout one of the most strife-ridden periods of a strife-ridden country’s history, to retain her questing and loving soul. Her poems are not about revolution or hunger or exile or suffering. But they could hardly be any more dramatic, with their focus on love in a time of carnage. Parnok managed to keep her libido and capacity for love intact without the buffer of wealth or station or political affiliation to bulwark her safety. And she loved and lived with a passion so enormous it is worth resurrecting and recalling, even as she has faded into history.

I think of her now because we are once again living in an age where to be who you are, for many people, will become a crime. No one embodied being who you are more enthusiastically than Sophia Parnok, who was seducing women until the day she died, and mocked Stalin’s Five-Year Plans by saying she only approved of five-year plans for kissing. She kept writing, even when, after 1927, she knew she could only write for “the drawer”—the place for poems that threaten authoritarianism. But she kept on with her florid and defiant paeans to the broken heart and the inflamed heart alike.

I think of her and remember that sometimes just being—being, joyously, all that you are, despite injunctions against that being—is enough. But for a lagniappe, she happened to write about it, with transporting joy and eloquence (and horniness). So I’ve translated a few of her poems for you, to keep my hand in (it’s nice as a translator that Parnok doesn’t employ the elaborate internal rhymes that other Russian poets do). And to pay tribute to greatness in all its forms—little and large and loving.

Kitchen Garden

The insatiable salt-soil’s eaten everything.

I pulled out the gnarled roots

Of curling vines that grew here once—

This humped, dry, scabbed earth

Like a hospital patient’s lips…

A calloused foot rests on a shovel

Under a torn sole…

Hands run through with heavy fire

Like a skull crushed by irons.

She, the earth, resisted me

With some ancient vengeance, but I

With a pickaxe, pickaxe—just like that, like that

I will outstubborn your stubbornness!

And frisky peas will raise their frills

And trunks of corn rise steeple-high,

And a monstrous potbellied pumpkin

Will fling out its serpentine braids like a Gorgon.

Ah, no snowdrop or crocus smells so of spring

As the first cucumber from the garden!

In the sun my sharp pick glitters like a fang,

Around me earth-clods bob up, crumble,

And a sea-breeze runs down my neck

And the sweat froze in a thin chill snake

And never, never has the pride of possession

Burned so with bliss unclouded through me;

And away in the valley the almonds were fading

And the peaches bloomed in their place.

Огород

Все выел ненасытный солончак.

Я корчевала скрюченные корни

Когда-то здесь курчавившихся лоз, —

Земля корявая, сухая, в струпьях,

Как губы у горячечной больной...

Под рваною подошвою ступня

Мозолилась, в лопату упираясь,

Огнем тяжелым набухали руки, —

Как в черепа железо ударялось.

Она противоборствовала мне

С какой-то мстительностью древней, я же

Киркой, киркой ее — вот так, вот так,

Твое упрямство я переупрямлю!

Здесь резвый закурчавится горох,

Взойдут стволы крутые кукурузы,

Распустит, как Горгона, змеи — косы

Брюхатая, чудовищная тыква.

Ах, ни подснежники, ни крокусы не пахнут

Весной так убедительно весною,

Как пахнет первый с грядки огурец!..

Сверкал на солнце острый клык кирки,

Вокруг, дробясь, подпрыгивали комья,

Подуло морем, по спине бежал

И стынул пот студеной, тонкой змейкой, —

И никогда блаженство обладанья

Такой неомраченной полнотой

И острой гордостью меня не прожигало...

А там, в долине, отцветал миндаль

И персики на смену зацветали.(1924)

Give me your hand, and let us enter our wicked paradise

Give me your hand, and let us enter our wicked paradise!...

In defiance of the plans of celestial industry and finance,

For us, May has returned in the midst of winter.

The green meadow is blooming,

The apple tree is all in blossom,

The fragrant boughs fan the earth, inclining

Towards an earth that smells as good as you do…

And butterflies make love in the air…

We are a year older, but it doesn’t matter, —

Old wine is a year older too!

And even more delicious are those dishes that mature…

My love, my gray-haired Eve! Farewell!

Дай руку, и пойдем в наш грешный рай

Дай руку, и пойдем в наш грешный рай!..

Наперекор небесным промфинпланам,

Для нас среди зимы вернулся май

И зацвела зеленая поляна,

Где яблоня над нами вся в цвету

Душистые клонила опахала,

И где земля, как ты, благоухала,

И бабочки любились налету…

Мы на год старше, но не все ль равно, —

Старее на год старое вино,

Еще вкусней познаний зрелых яства…

Любовь моя! Седая Ева! Здравствуй!(1932)

Let Us Be Happy at Any Cost

Yes, my friend, happiness came into my life!

Now fatal weariness closes my eyes and soul.

Unrebelling, unresisting,

I weaken, and the bond slackens

That once cinched us so tightly.

The wind, unfettered, blows free and high, and higher,

Everything blooms and all is quiet —

Goodbye, my friend!

Can’t you hear?

I part with you, my distant friend.

«Будем счастливы во что бы то ни стало…»

Да, мой друг, мне счастье стало в жизнь!

Вот уже смертельная усталость

И глаза, и душу мне смежит.

Вот уж, не бунтуя, не противясь,

Слышу я, как сердце бьет отбой,

Я слабею, и слабеет привязь,

Крепко нас вязавшая с тобой.

Вот уж ветер вольно веет выше, выше,

Все в цвету, и тихо все вокруг, —

До свиданья, друг мой!

Ты не слышишь?

Я с тобой прощаюсь, дальний друг.(1933)

Yes, I am Alone

Yes, I am alone. At the hour of parting

You predicted orphanhood for my soul.

Alone as the first man in the universe

on the first day of creation!

But the vain oath of your anger

Is fated not only for me —

Those who are pure of soul confess

Orphanhood, too, do they not?

There is no one better and higher

Who would not, if only once, and grieving

Wince at that line of Tyutchev’s —

“How can another understand you?”

Да, я одна

Да, я одна. В час расставанья

Сиротство ты душе предрек.

Одна, как в первый день созданья

Во всей вселенной человек!

Но, что сулил ты в гневе суетном,

То суждено не мне одной, —

Не о сиротстве ль повествует нам

Признанья тех, кто чист душой.

И в том нет высшего, нет лучшего,

Кто раз, хотя бы раз, скорбя,

Не вздрогнул бы от строчки Тютчева:

«Другому как понять тебя?»(1915)

-

Damn girl, I'm feeling stronger now. I'm going to pick around in my kitchen garden, eat a grilled cheese and live. Beth

-

Having listened to your exquisite reading of your latest book I'm here begging you to read these for us in English and Russian. Please? Pretty please?

-

This!!! I second Beth’s comment, this is making me feel alive again. It was what I needed today. Thank you, for this and so much more. Going to share this around with all my queer friends now!!

-

Thank you so much for this <3

-

oh damn this is some really lovely poetry/translation. I need to drink some wine and roll in some dirt

Add a comment: