How to Not Get Poisoned in America

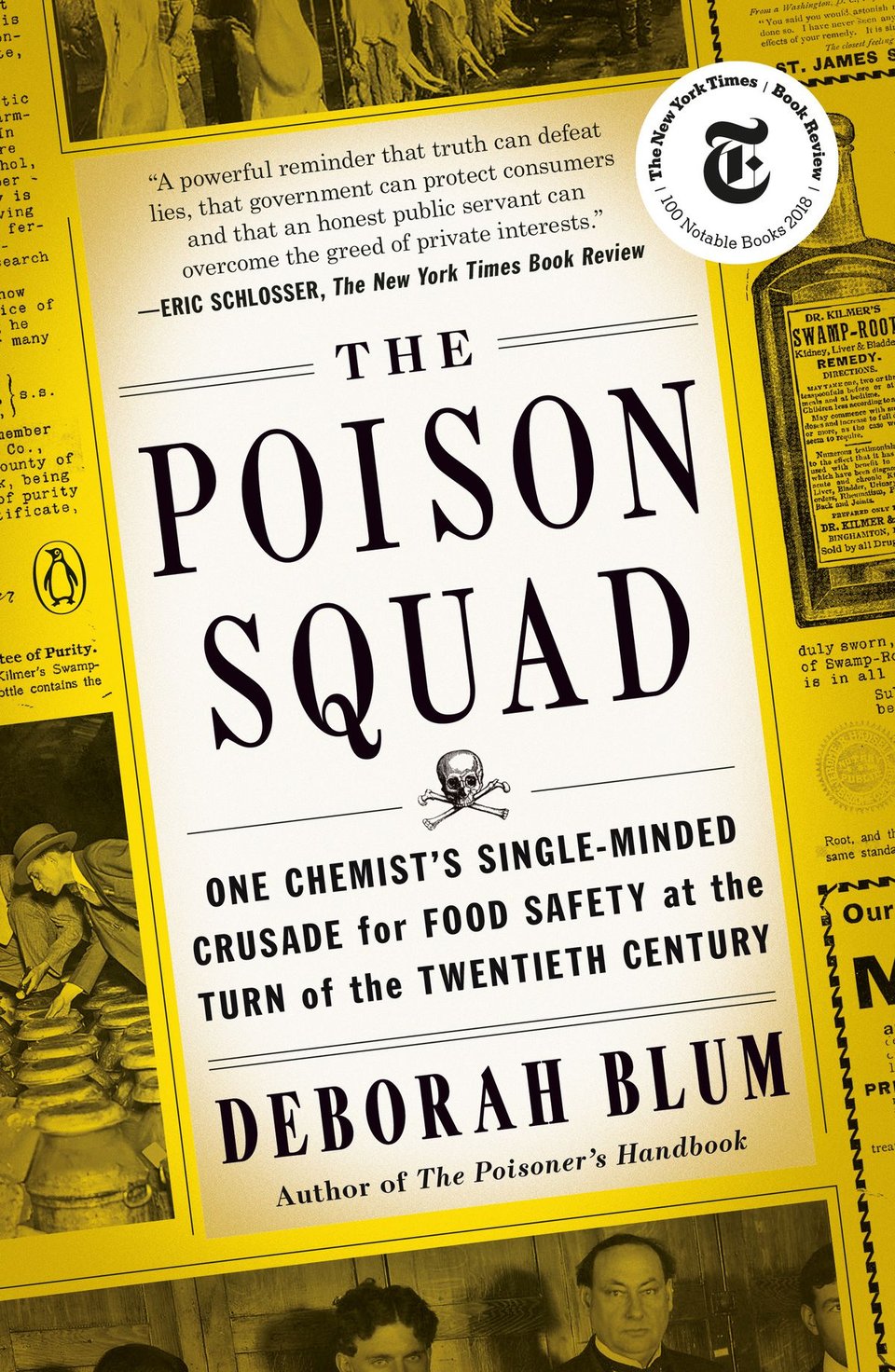

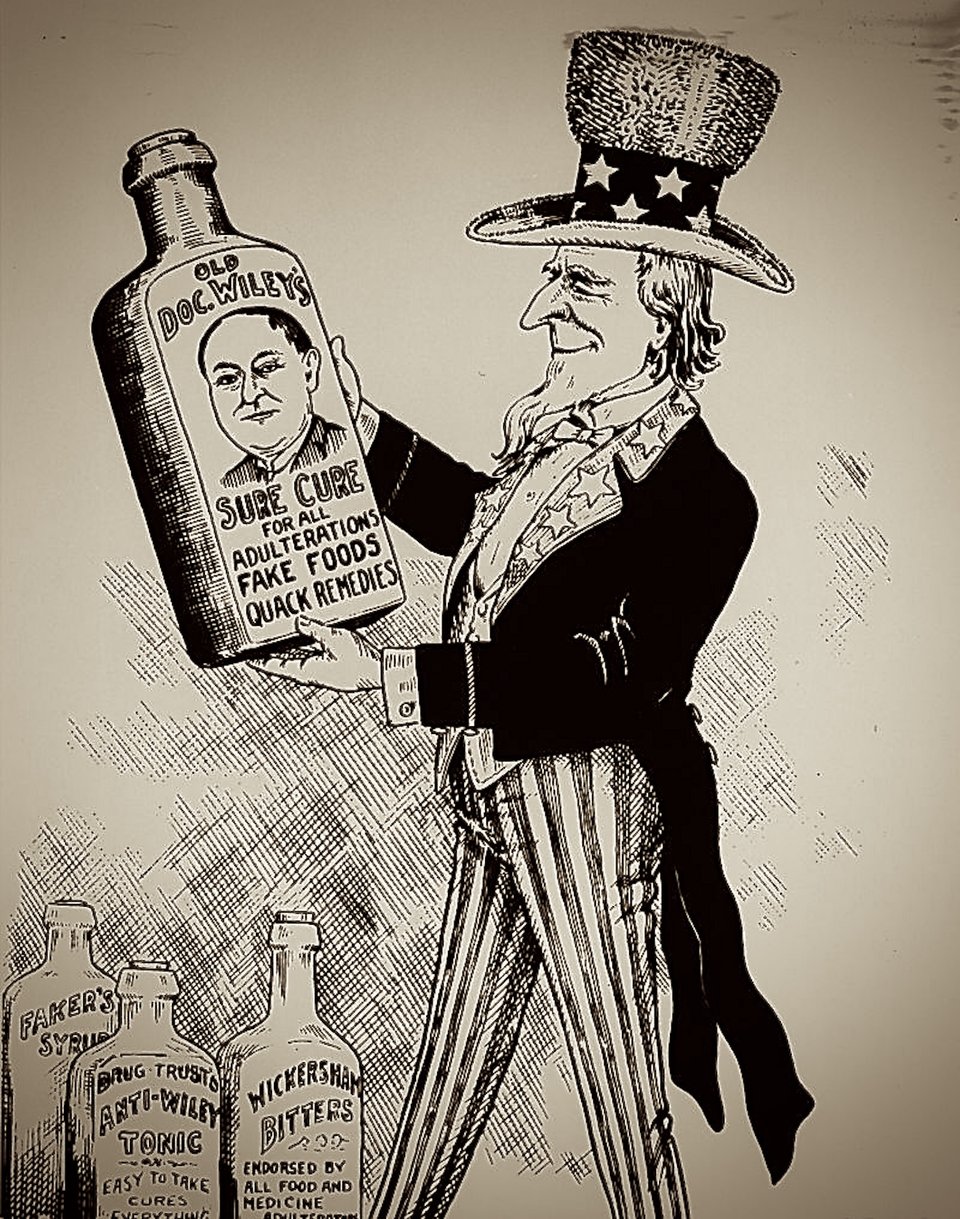

The minute I saw that Robert Kennedy Jr., a notorious disease-loving health crank, was going to be responsible for the nation’s health—and the health of its food supply—I knew who I had to call. Deborah Blum is the woman who literally wrote the book on the history of US food regulations. In 2018, she published “The Poison Squad: One Chemist’s Single-Minded Crusade for Food Safety at the Turn of the 20th Century,” a fascinating and occasionally harrowing account of how the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906—which led to the establishment of the FDA—came to pass. Blum is an expert on poison; her 2011 book “The Poisoner’s Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York” also contends with poison, intentional and unintentional, and the law.

Blum is also the director of the Knight Science Journalism Center at MIT during a particularly difficult time for science journalism. Under an administration ravenous for deregulation, which, when it comes to food safety, hits us right in the gut, I wanted to talk to Blum about how she’s processing the news; the Wild West of pre-regulation American food, and our chances of returning to that unhappy state; and what it’s like to write about science in the face of administration hell-bent on dismantling the U.S.’s world-class scientific establishment. Along the way, we touched on low-dose toxicology, attitudes in the US about money, food, and individualism, and the impossibility of being an informed consumer in an age of disinformation. It was a fascinating conversation, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity (and to fit into an email).

I guess my first question is: What does it feel like to be a science journalist right now, and to be someone who teaches science journalists?

We’re seeing a federal administration that’s spreading misinformation about science left and right. I'm thinking vaccines, or the autism crap that comes out of the administration. In general, they rely on misinformation about science, and they misstate what agencies are doing, what research projects are doing, and why they matter. They remove information about climate change. They are removing our ability to actually accurately forecast. If you're a science journalist, your job is to factually explain what science is and how it works and why it matters. We've had this kind of existential conversation about whether we’re doing the job right, and getting the information out. I would argue to anyone: We're certainly doing a first class job of educating the kind of people who read the New York Times. But they're not the audience that we need to reach. So the second part of the conversation we've had is, how best do we counter misinformation? Which is an enormous task when your government is not honest about science. How do you establish yourself as a trustworthy source when your government spends a lot of time trying to persuade the American people that journalists can't be trusted, and that scientists can't be trusted?

I think we do a pretty good job of educating people who are already educated—people inside the coastal bubbles—but it's the people that we're not reaching who are bringing us some of the problems we see today. You know, they buy into vaccine misinformation, so measles is spreading everywhere. It's frustrating, but it feels like a really important time to be a science writer because telling the story of science accurately and well—and letting people know what happens with climate change, with infectious disease, with food safety, with all of the things that we do—is more important than ever.

Absolutely, but it seems to me that the incentive structure, and what makes for prestige in the journalism world, really doesn't fit with reaching these wide audiences, people who are not news consumers in the traditional sense. That really creates a tremendous level of difficulty before you even start.

I think we particularly see that in the warping of political coverage in the United States. There are so many political writers and correspondents who are so caught up in the access-prestige game that they don't cover things in a way that might annoy people in power. I'm saying that as nicely as I can. We also have to acknowledge that we've been busy in this country destroying local journalism. Meanwhile, local journalists are often unsung heroes, doing some of the best work right now on air quality, on safety, on climate change in their communities. Some of the destruction is due to places like Alden Capital buying up newspapers and stripping them down for parts. Right now I'm gonna sound like an advocate: we have to change this. It's not acceptable. It's putting the country at risk. It's putting all of it at risk.

Going back in time a little bit, what inspired you to write The Poison Squad in the first place? What made you sit down and say, I'm gonna write a history of food regulation in America?

That's a good question, because I don't have a deep background as a food writer, but I am a toxicology journalist and that's kind of what brought me there. I've been writing about poisons in everyday life, the chemistry of everyday life, for about 15 years. The first book I did on the subject was The Poisoner's Handbook, which got me really interested in two things. One is the early history of our exposure to toxic chemicals in the United States, and the second is that I'm interested in the way very stubborn, difficult people can change a conversation. Most of the people who actually drive a paradigm shift or a change in a conversation are obsessive, obstinate, never-give-up kind of people.

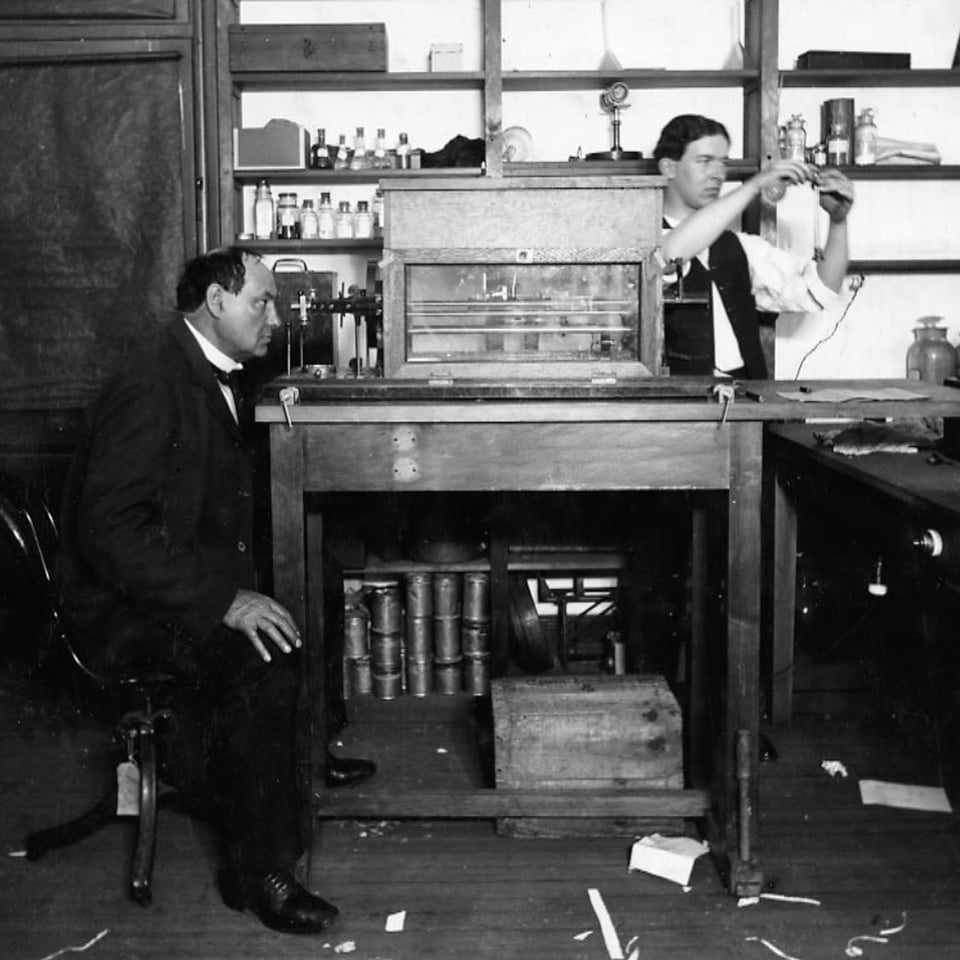

With The Poison Squad I was just sort of poking around that question: what were people really exposed to in the early 20th century? And I saw references to this experiment that the Washington Post had called the Poison Squad, run by a USDA chemist, Harvey Washington Wiley. I thought, well, what is that? That's how I started. So I went and looked at that experiment—a very peculiar public health experiment in which you have a senior chemist at a government agency poisoning his coworkers. The Poison Squad was a group of young clerks at USDA who ate meals that included food additives that Harvey Wiley thought or suspected were truly dangerous. And I thought, why would you do that? Why would you feel that the only way that you could get at a problem would be to poison your coworkers?

That led me into something that I actually had not expected to find. I started looking at what brought him to this point of desperation, because you have to be pretty desperate to do an experiment on your colleagues where you're having them eat capsules of formaldehyde. When I went back to the 19th century, I realized I had bought into this mythology of the happy, pink-cheeked Americans eating their farm-fresh food, and everything's wonderful. And you get this sometimes from, you know, super foodies. They'll be like, don't eat anything your grandmother wouldn't have touched or couldn't spell. Yeah, but your grandmother was eating crap. The food supply, the commercial food supply in the 19th century, was awful. And I hadn't realized that, so I started really getting into the subject: what was going into food in the 19th century? Really bad things, for reasons of profit primarily. And why weren't we doing anything about it? That was the other question for me.

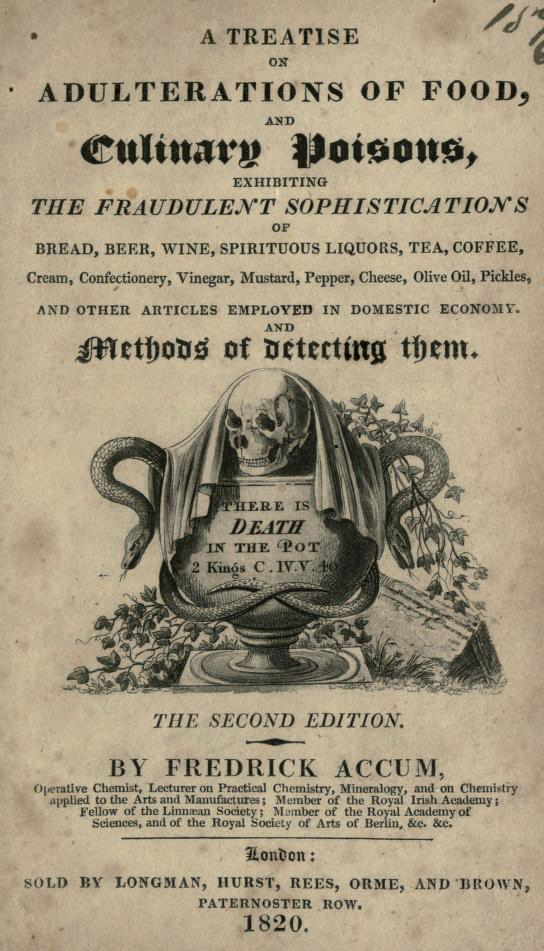

That's really where the Wiley story comes into it. You have all of these different really bad things that are going into the industrial food supply. In England, there's a book, A Treatise on Adulteration of Food and Culinary Poisons, that came out in 1820 that talks about the use of heavy metals in the food supply—arsenic as a green food coloring, copper sulfate as a green food coloring, lead as both a yellow and orange food coloring. And eventually, through that and a series of scandals, Britain passed a food safety law in 1860.

But there's nothing in the United States, and yet the same things are in the food supply. There's two things going on. One is the food supply is full of all kinds of incredible fakery. You could put anything into a can of coffee or a jar of jam or flour or whiskey, and you didn't have to label it, and you didn't have to safety-test. So when Harvey Wiley becomes a federal chemist in 1883, he starts just by investigating. He wasn't a crusader, he just launches this series called “Bulletin 13”, which consists of investigations of the American food supply. And he finds all the things I'm telling you about, really poisonous things in the food supply.

You know, as an example, red lead was used to make cheddar cheese look orange. There's no redeeming quality to eating lead, right? It is bad at all doses. And so is arsenic for green food coloring, powdered tin to make chocolate shiny, formaldehyde to preserve milk, borax going into the food supply as a preservative. A can of coffee could be coffee, but it could be ground bone, or charred shells, or dirt. Your can of ground cinnamon could be cinnamon, but more likely it’s brick dust. Your flour could be flour, but more likely it’s cut with gypsum, which is drywall. Salicylic acid, the active compound in aspirin but which causes stomach bleeding in high doses, is used as a preservative.

There was a pepper dust example where it's literally just dust.

Yeah, they've just swept the floor and dumped it in the can. It's crazy, and it's all legal, and you don't have to tell anyone. And so you see Wiley in these Bulletin 13 reports get more and more pushy: “Could we at least label this? I mean, you have people who are eating this food that has something that causes the lining of their stomach to bleed five times a day. Shouldn't they know that?” And nothing happens because basically Congress is really corrupt. The more things change, right?

On that note, I know you’ve been following the recent news about food deregulation under the Trump administration. How is it making you feel?

It's making me really ticked off. You know, no law's ever perfect. The original Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 wasn't perfect. We updated it in 1938 with the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act, which is better. We've been trying to improve those regulations ever since, and I really believe these regulations have saved countless lives. A lot of food historians will tell you that food was one of the top 10 causes of death in the 19th century. That's not true today. People get food poisoning, people die, but it's far, far, far from one of the top 10 causes of death. These rules have made us safer, so we don't wanna undo them. We don’t have to repeat every mistake we’ve ever made.

So I think, again, we should go back into history and ask: Why did we need the federal Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906? There were states that had food safety laws, and some of them had pretty good food safety laws, considering. But the thing is, when you looked at it, what you saw was that some of them had food safety laws, and some of them had none. And what you needed was a national standard that everyone got held to. So if we go back to this, where the states will take over facility testing, some of them will, and some won’t. Minnesota has a very good food safety program, for instance. Mississippi doesn't.

So then the question becomes: should you be poisoned by your food by virtue of what state you're born into?

That's exactly right. And there are things that the FDA does that the states have never done. The FDA inspects food that's imported. And they do inspections of factories that process offshore, outside the US, but send the food here, and they analyze products that come into the United States. There's no state that does that testing. And I was actually talking to one of the people who runs one of the FDA Foreign Product Safety labs awhile ago, and he said they were flagging olive oil coming from Europe–it was cottonseed oil and they were using a 19th century dye, copper sulfate, to make it green, because they wanted it to look like green olive oil. And so the FDA steps in. When we take away those labs, we don't get those safety checks. So are we making the food system less safe? Of course we are.

Is there any reason to think that corporate behavior will have changed in the ensuing hundred years, or are we looking at blanket opposition to food safety on behalf of profit?

I don't want to sound as if the whole food industry is corrupt, because I don't think that's true. And I don't necessarily think that was even true in the 19th century, although there were manufacturers in specific niches who were very dishonest, and who targeted people who didn't have very much money. And so a lot of the worst of the adulteration was aimed at the people who couldn't afford the expensive, really good, carefully maintained and packaged food that you could get when you were wealthy. I don't think that's changed. I don't think that's changed for a minute. If you look at the Boar’s Head recall, which was just last year, you saw a factory cutting all kinds of corners and that was a fairly respected national brand.

And now I can't get liverwurst anymore.

I know, it's really annoying. I love liverwurst. But, if I was gonna pick a company that I thought was gonna engage in shoddy processes to make a little extra money, I wouldn't have picked that one. So we can't just say, well, no one does that anymore because we have evidence from not that many months ago that that happened. There are always gonna be those bad actors.

You probably saw the story about the romaine lettuce investigation—there was E. coli contamination that sickened people in a number of states in the fall. And the Biden administration launched an investigation that concluded in February, and the Trump administration has refused to release the results. They won't say what happened. They won't even say what companies are involved. And so what we are seeing with this federal government is a food contamination case in which the government is conspiring to cover it up. I just...my hair is gonna catch on fire. I'm one of those annoying people who stands in the grocery-store aisle reading labels. But most people don't have the time, and the labels themselves–we have labels thanks to Harvey Wiley—but are they a hundred percent transparent about everything? No, of course they're not.

And do the labels say there were five salmonella outbreaks at this factory in 2022? Does it say exactly under what conditions this bag of spinach was produced? No one can know that at the point of consumption!

I do not think the FDA has been perfect at this, but there's no way for each of us as individuals to stay on top of it all. But an agency dedicated to food safety can do a much better job, and should.

It becomes this almost parodic, end-times iteration of American individualism where if you die of tainted food, it's your fault, but you can't know if the food is tainted. And so it begins to look a little bit like eugenics.

Well, RFK Jr. sure sounds like a eugenicist half the time, if not all the time.

Speaking of unwelcome trends from the early 19th century that are being revived. But if you die of listeria-tainted lettuce because you were trying to do something healthy for your family, that's not your fault. And you want a nice treat and there’s powdered tin in your chocolate and you get sick, that’s not your fault either! There just needs to be a mechanism in place to keep that from getting to your shelf and your table.

It's like when Wiley's department sent out guidance about how to do home chemical experiments on your food, to detect adulterants. We don't wanna go back to that. There's no way for us to keep track of all this information. I worry that we are going to see uninspected factories put out really bad stuff, uninvestigated outbreaks piled on uninvestigated outbreaks. I'm not predicting a dystopian landscape of food at this point, but I think this administration is actively making all of us less safe.

Are we looking at a future where brands are advertising being free of contaminants, and that's a luxury only affordable for the rich?

As a country, we tend to suffer from what I think of as regulatory memory failure. We don't have a sense of what things were like before regulations went into play. Most Americans don't really have a sense of what the environmental landscape of the United States looked like before the EPA, for instance. Instead, we demonize regulation, when often we're really talking about consumer protection. And when we're talking consumer protection, we're talking about protection for every American citizen. But until you have those kinds of universal standards in place, the people who suffer the most are going to be the people who can't afford the good stuff.

That was one of the things that I wrote about in The Poisoner’s Handbook: the disproportionate effect of Prohibition on people who had no money. They ended up with the really poisonous alcohol, whereas the F. Scott Fitzgeralds of the world always had the good stuff. They weren't being poisoned.

If you look at the 19th century, what you see is the worst of the food abuses are really being felt by working class families, who can only afford adulterated food. There was an example I used in the book about strawberry jam that was just corn syrup, coal tar dye, and grass seed. And the manufacturer said, Well, that's the competitive thing in that market. We can't afford to put anything good in it, like actual strawberries. It always disproportionately affects people who have no money. Some of the things we worry about in food are what I think of as low dose toxicology, right? I got really interested in the issue of arsenic and rice. That's a naturally occurring contamination, especially in brown rice products, which retain the husk. Rice likes metals, and it just pulls it out of the soil—it has a good metallic element transporter system. Anyway, the trick with something like that is you don't eat it every day, because when you're exposed to very low levels of toxic compounds, you want to give your body some time to heal. Arsenic metabolizes out of your body in two days. So you can say, well, don't eat rice every day. Eat it once or twice a week if you're worried about arsenic.

But there are people who can only afford to eat rice every day!

That's exactly the point. It’s a rich person's advice. I used to go out and I'd say, “variety is the spice of life, mix up your diet.” That'll protect you if you can afford it, but if you can only afford the box of orange-colored mac and cheese every day, that's what you're going to eat. That is why we say consumer protection is an equalizer: it protects everyone equally.

I'm out of patience with American individualism. Either we're in this together and we're a community, or we aren't. And I want us to be a community. I've been quoting Orwell recently. You know, the famous line from Animal Farm, “all animals are created equal, but some are more equal than others”? I don’t believe that for a minute. I wish we could get on the page of saying that on some level, we are in this together, and we take care of each other.

Especially in a landscape where both poverty and food consumption are so tied into these complex ideas of virtue and guilt. Are you worthy? Are you worthwhile? And if you eat the orange mac and cheese because you can't afford anything else or anything healthier, you're sinning somehow. It's very Calvinist. It's very individualistic. And it’s literally poisoning us.

I actually went to a lecture by a famous American foodie who was like, people who eat fast food just don't have the same kind of moral fiber of those of us who are eating air chilled chicken. I left. You eat what you can afford, and if you don't have any money, and a big treat is for you to take your kids to McDonald's, that's just you trying to do something nice for your kids within the budget you have. It has nothing to do with moral fiber.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

I do think there is this sort of moralizing element about food—both the types of food you eat, and poverty in general—that makes us more vulnerable to this kind of eugenicist individualizing, and dismantling regulatory structures.

Trump is forever talking about people and their good genes. You forget that when we protect the least of us, we protect all of us. Even if we don't want to be, we are actually in this together. Eugenics is just garbage anyway.

So when we look at Harvey Washington Wiley and his poison squad and his support for the Pure Food Act, it took a long time. Decades. What kind of political headwinds was he facing down during those decades, and do you see parallels to those headwinds now?

One of the things that I realized when I was researching The Poison Squad is that business had never been regulated in this way. No one had told American businesses that they couldn't put something in food, or that they had to be honest on a label. And after the law, what you start seeing is this really cozy relationship between American business and American government at the national level. There's like the secret handshake, which the rest of us don't see, because we don't have that kind of access and power and money. And that really shaped the way that the Food and Drug Act was actually implemented.

If you're in an industry that's always been able to do whatever it wanted, you wouldn't exactly be throwing your arms around safety standards. That would cost you money. When I was hanging out with the food safety people at the FDA, the staff appointees—which our president would call the deep state—would talk about all the times they had moved to do some kind of safety thing for food and been overruled by the political appointee who was best friends with someone in industry. The forces that weakened the Pure Food and Drug Act as soon as it passed–we see those same forces today. American industry has done a world-class job of demonizing the word “regulation,” as if it's something innately evil that has prevented us from being what we were until Trump came into office… which was the most successful economy in the world.

You know, I did a piece for The New York Times about food safety, where I talked to a couple of friends of mine who are more deeply involved with the FDA than I am. And both of them said, don't put in there that the FDA is perfect. They're like, there's lots of problems with the FDA. But do put in there that we need these safety standards in place. There are modern iterations of Harvey Wiley doing their best to look out for us. We should count our blessings in that.

You hear a lot that every safety regulation is written in blood, and once you dismantle a safety apparatus it takes twice as long to build it back. But at the same time, you can't snap your fingers and get rid of 100 years of people having the expectation that they go to the supermarket, buy food, and it doesn't kill them.

That’s where I think journalists and advocates really come in. You probably saw that some of the people whose children died in the measles outbreak in Texas were still explaining that they had done the right thing by their kids, because they're sucked into the science misinformation loop. It's really important that if we have a food outbreak and our federal government is taking the path of covering that up, that there are people who are getting that information out.

So the last real question I have is “if Harvey Washington Wiley was revived right now, how mad would he be?”

Oh, I imagine him even now spinning in his grave. I mean, he was completely uncompromising, and that worked both for him and against him. It worked for him because he got things done, and it worked against him because sometimes you actually have to compromise and get along with people to get things done right. But I think that he would have been pretty satisfied with how far we came leading right into the first Trump administration. When Wiley was working to try to get the Food and Drug Act passed, and it kept failing, one of the Congressman he worked with said to him, flat out, you'll never get this passed until the American people stand up and say, we want this. I'm not arguing that we should be hamster-on-a-wheel type informed consumers, exhausting ourselves, researching everything we eat and drink. There's no way to do that. But I am saying that we do make a difference when we stand together.

At the end of the day, what I'm getting from your work is this idea that all of us—rich or poor, young or old, informed or uninformed—have a fundamental right to go to the store and buy food for ourselves and for our families that won't kill us and make us sick.

When we talk about fundamental individual rights, one of them is the right to be safe and protected in your everyday life. You know, there's that clause in the Constitution, “promote the general welfare.” What does that mean? It means protect us in our everyday life. We have the right to expect our government to do that. We have the right to go out and put together a sandwich and have it not kill us. That's a fundamental right, and the country is stronger when that right is in place.

Every person matters. Our government should protect us in an every person way, and we should stand together in an every person way. I've got two sons, and my older son used to say to me, Well, why should I vote? And I say, because all the individual votes add together. It's like one drop of water. You put all the drops of water together, you get a wave. Be the wave, right? That sounds so hokey when I say it, but I think that's where our power is. This is a good time for us to know that, and to use it.

-

Quick appreciation for your bookshop.org links!

-

I think we need to have a conversation about how Liberal food moralizing/shaming (in conjunction with fat/bodyshaming) has to be called out and forsaken in order for any pushback against RFK Jr. to work. Because here's the thing... It's still going on with their cracks about Cheetos and Mountain Dew, using fatmisia to dunk on Trump and his supporters like you can determine someone's political party by their body type. Erewhon Liberals share more in common with RFK than they'd like to admit right now. But when anyone to the Left of them with a praxis around destigmatizing food choice and body type brings this up, they can't have a productive conversation. This idea that orthorexia = intelligence and worthiness had some supporters who are acting like they hate everything about this. #HonestyHour

-

So grateful for this simultaneously disgusting and encouraging column. Thanks, Talia and Deborah!

Add a comment: