Donald Trump's Dictator Chic

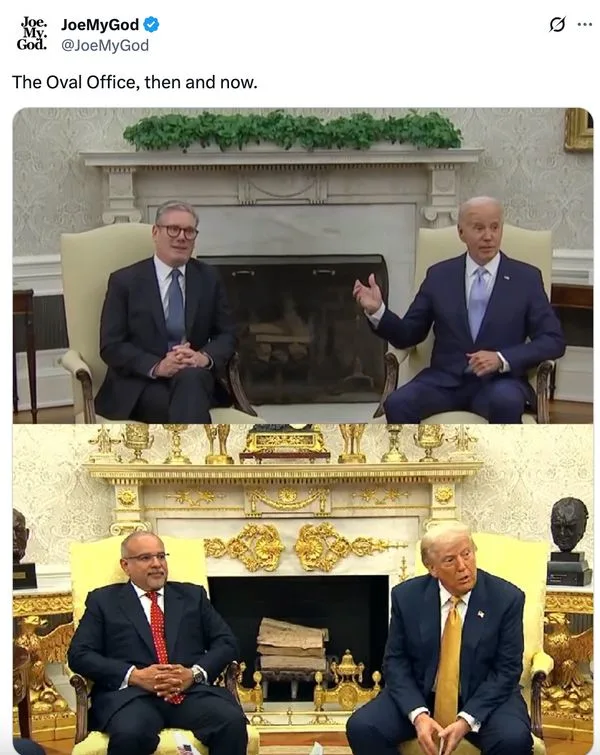

Last week, the hoax-busting website Snopes felt compelled to fact check the Oval Office. Specifically, a reader had written in, asking whether a viral photo comparing the iconic room from Biden’s tenure to its present incarnation under the second Trump regime could possibly be legitimate. Snopes confirmed that the image was indeed real: “The gold elements include historic items from the White House collection dating back to the early and mid-19th century, positioned on the fireplace mantle. Additional decorative elements included gold cherubs above doorways, gilded mirrors, gold eagles on side tables and a gold-plated replica of the FIFA World Cup trophy behind the Resolute Desk.”

If today’s Oval Office conjures images of Louis the XIV eating Versailles, and then vomiting all over the White House, we can thank Trump’s personal preferences, as well as the Mar-a-Lago decorator who the president brought in to add his rococo touch. “A cabinetmaker from south Florida who has worked on projects at Mar-a-Lago, John Icart helped add custom-made gold finishes to the Oval Office, including gilded carvings for the fireplace mantel and the molding that wraps around the most famous office in the world, administration officials said,” wrote the Wall Street Journal. “It’s the Golden Office for the Golden Age,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said in an email. Around the White House Icart is known as “the gold guy.”

But all that glisters is not gold, and today’s presidential workplace is more like the Gilt Office for a new Gilded Age. Two years ago, I wrote about the origins of Donald Trump’s faux-imperial aspirations, and looked at how it both evoked and strayed from a historically dictatorial style of decoration. Given the attention being paid to the new-look Oval Office—and because Talia is unfortunately a bit under the weather today—it seems like a good opportunity to revisit its roots.

Among the other articles I assembled was a 1988 Vanity Fair profile of Ivana Trump. In it, the first Mrs. Trump fantasized about all the improvements she could make to the White House once her husband was inevitably elected president. “Imagine a First Lady who could redecorate it more professionally than any of her predecessors,” wrote Michael Schnayerson, “And who’s to say the Oval Office wouldn’t look better in pink marble with a waterfall along one wall?” Those particular features are unlikely, but Trump does have a new White House ballroom in the works, as well as plans to turn the Rose Garden into a Mar-a-Lago-style patio. Ivana, of course, is not around to see it all.

— David Swanson

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

June 11, 2023

Among the Thugs

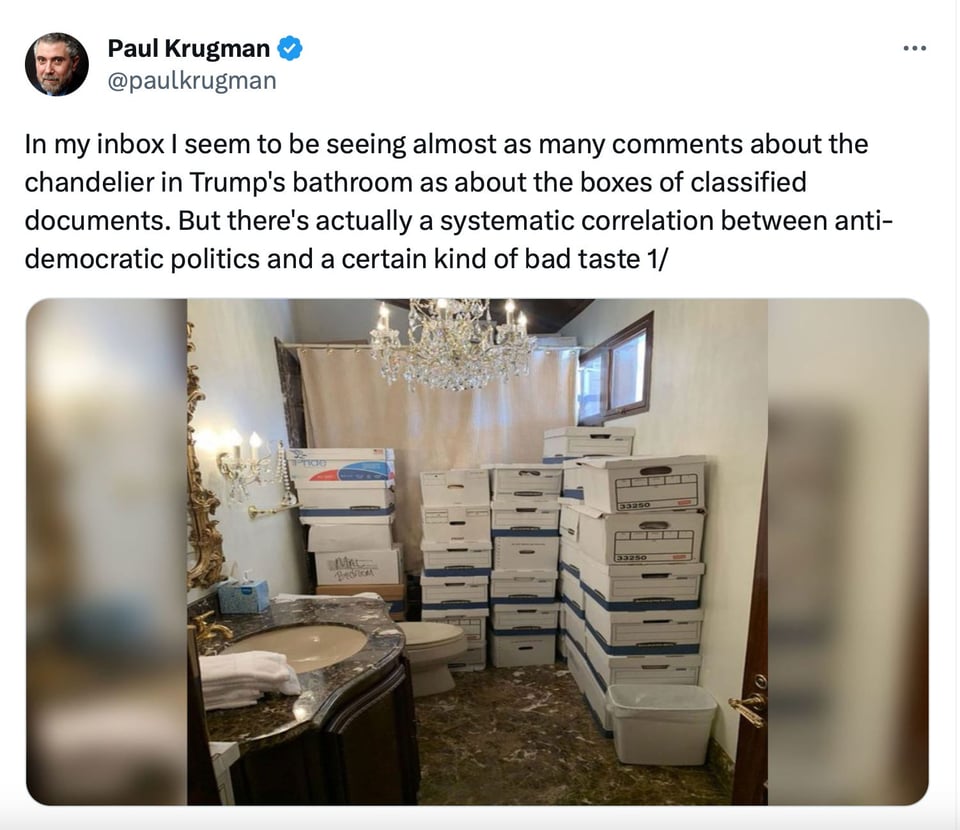

This weekend, after photos were released showing government boxes stacked in a conspicuously ornate Mar-a-Lago bathroom, the decor got nearly as much attention as the treason. Paul Krugman tweeted that Donald Trump’s particular brand of “bad taste” seemed to suggest authoritarian inclinations:

Krugman went on to share “Trump’s Dictator Chic,” a 2017 Politico article by Peter York, design columnist for Britain’s Sunday Times and author of 2006’s Dictator Style: Lifestyles of the World’s Most Colorful Despots. “At one level, [Trump’s style] is aspirational, meant to project the wealth so many citizens can only dream of,” wrote York. “But it also has important parallels—not with Italian Renaissance or French baroque, where its flourishes come from, but with something more recent. The best aesthetic descriptor of Trump’s look, I’d argue, is dictator style.”

York’s piece sent me down an online rabbit hole of reading into where Trump got his taste, and who might have inspired it. As you might have guessed by now, that rabbit hole inspired tonight’s newsletter, another dive into the internet’s vast reservoir of archival magazine content. I found a number of juicy features on Trump’s initial glass-and-brass-fueled rise and fall—including a pair by Marie Brenner, in New York and Vanity Fair, respectively—as well as two good New Yorker pieces by Adam Gopnik about the history of the modern tyrant.

When you start obsessing over the lives of humanity’s most evil specimens, it rarely ends well. But I was shocked to discover how humanely these monsters were portrayed in the contemporary press. Whether it’s the Atlantic on Mussolini, the New Yorker on Hitler, Stalin, or the New York Times on Mao, the subjects are inevitably depicted as men of the people who would gladly spend more time with their doting families—if only there wasn’t so much work to do on behalf of their devoted subjects.

These stories also suggest that the twentieth century’s worst dictators were more interested in power (and cruelty) for it’s own sake than is our current crop of would-be autocrats, whose primary concern seems to be the pursuit of luxury. A century ago, Mussolini—the original fascist blowhard—would have felt right at home in Trump’s sitting room at Mar-a-Lago … but he would have turned it into his office.

Donald Trump’s Gilty Pleasures

Trumping the Town

By Marie Brenner

New York Magazine, Nov 17, 1980

“Their house isn’t a home; it’s a stage set: platforms, mirrors, twinkly lights, a bar, black malachite cube coffee tables, shell and silver accessories from Carole Stupell, no toys on the floor for a three-year-old, no clutter, just hard-edged charm. The Trump apartment looks like one of the luxury suites at the Grand Hyatt, a place designed for the future without a thought to the past, a place designed to entertain in, impress, ascend. A place just like Trump Tower will be, a monument where out-of-towners like the king of Saudi Arabia, Sofia Loren, and Donald and Ivana Trump will live.”

Inside Ivana’s Role in Donald Trump’s Empire

By Michael Shnayerson

Vanity Fair, January 2, 1988

In the limousine, we move on to happier subjects. How does she feel about all this talk of Donald running for president? And is her own ultimate goal to be First Lady? “It’s not for the next ten years, definitely not,” Ivana replies quite seriously. “There is so much to do. We have invested in this town close to a billion dollars. We can’t just put it in escrow and go to the White House. It would go down the drain in a second. It’s too young, too new. But in ten years Donald is going to be just fifty-one years old—a young man. What he’s done in the last ten years some corporations don’t do in a hundred years. Donald is interested in politics at a certain level. But I don’t think he would run for mayor—he could do that so easily. That wouldn’t be a challenge for him.”

Ivana may also feel that the White House would provide a better showcase for her own talents than Gracie Mansion. Imagine a First Lady who could redecorate it more professionally than any of her predecessors. (And who’s to say the Oval Office wouldn’t look better in pink marble with a waterfall along one wall?) Ivana’s European perspective wouldn’t hurt, either: she speaks fluent German, French, Czech, and ... Russian. With her casino savvy, she’d be a perfect consultant on the economy. And for the all-important task of overseeing White House social affairs and the service staff, what better experience could one have than overseeing not one but three palatial residences?”

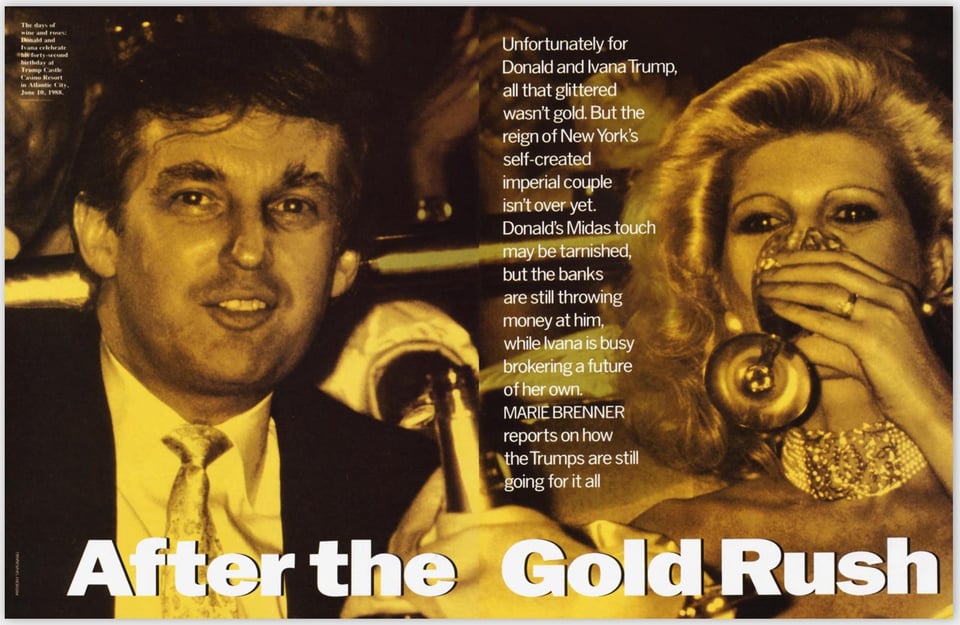

After the Gold Rush

By Marie Brenner

Vanity Fair, September 1990

“We have an old custom here at Mar-a-Lago,” Donald Trump was saying one night at dinner in his 118-room winter palace in Palm Beach. “Our custom is to go around the table after dinner and introduce ourselves to each other.” Trump had seemed fidgety that night, understandably eager to move the dinner party along so that he could go to bed.

“Old custom? He's only had Mrs. Post’s house a few months. Really! I'm going home,” one Palm Beach resident whispered to his date.

“Oh, stay,” she said. “It will be so amusing.”

It was spring, four years ago. Donald and Ivana Trump were seated at opposite ends of their long Sheraton table in Mrs. Marjorie Merriweather Post’s former dining room. They were posed in imperial style, as if they were a king and queen. They were at the height of their ride, and it was plenty glorious. Trump was seen on the news shows offering his services to negotiate with the Russians. There was talk that he might make a run for president. Ivana had had so much publicity that she now offered interviewers a press kit of flattering clips. Anything seemed possible, the Trumps had grown to such stature in the golden city of New York.

Donald Trump’s Tower of Trouble

By Wayne Barrett

Village Voice, December 17, 1991

When Trump Tower opened in 1983, its golden entrance, 80-foot waterfall, and rose-peach-and-orange-colored marble atrium quickly established themselves as the most photogenic symbols of Trump glamour. Donald launched a $2 million promotional campaign, complete with a lavish brochure promising the ultimate in luxury—hairdressers, masseuses, limousines, helicopters … all at your service with a phone call to your concierge—making the tower the place to buy. In a masterstroke of media deception, he even floated the rumor that Prince Charles was thinking of moving in at Fifth Avenue and 56th Street. But the clientele never did get that exclusive…

Your Trump Tower neighbors are as likely to be Medicaid cheats, coke dealers, mobsters, or those who may have gotten a touch too friendly with mobsters. Take, for example, Verina Hixon, a strikingly beautiful Austrian divorcee with no visible income (or alimony), who, in 1982, bought six apartments on the tower’s 64th and 65th floors for about $10 million. (Trump Tower is really 58 stories high, but Donald had juggled the floor numbers, skipping 10 flights and renumbering it as if it were a 68-story structure.)

The Authoritarian Style

Donald Trump Has a “Dictator Chic” Design Taste

By Peter York

Politico, March/April 2017

“Dictators’ homes aren’t for one’s family, friends or private self; they’re not a refuge from the world or the job. Dictators’ homes, in fact, are the job—a place to do business, harangue people and settle scores, all while one’s entourage stays nearby. They are an architectural and artistic means of establishing the power of the occupants, of intimidating and impressing any visitor…

“In late 2015, I came across a set of pictures with no identifying text. They appeared to show a gigantic apartment in what looked, from the windows, very much like New York. But I know Manhattan and its sophisticated style pretty well, and at first glance, you would think the place didn’t belong to an American but to a Russian oligarch, or possibly a Saudi prince with a second home in the United States. There were overscaled rooms, and obviously incorrect-looking historical detailing and proportions. The home had lots of gilded French furniture and the strange impersonal look of a hotel lobby, with chairs and sofas placed uncomfortably far from one another. There were masses of gold; there were the usual huge chandeliers, branded relics of famous sportsmen like Muhammad Ali, and mushroom-colored marble floors. There was relatively little in the way of paintings, but otherwise, the place reeked of dictator chic.

As it turned out, this familiar yet unfamiliar apartment—a familiar style to me by then, but in an unlikely location—belonged to Donald Trump.”

The Field Guide to Tyranny

By Adam Gopnik

The New Yorker, December 16, 2019

The difference between charismatic leadership and the cult of personality—different points in the trajectory of the dictator—is that the charismatic leader must show himself and the object of the cult of personality increasingly can’t show himself. The space between the truth and the image becomes too great to sustain. Mao, like God, could be credibly omniscient only by being unpredictably seen. Imposing an element of mystery is essential. And so most of the subjects here rarely made public appearances at the height of their cults. Stalin and Hitler both remained hidden for much of the war; to show themselves was to show less than their audiences wanted…

Donald Trump likes dictators not only because he likes authoritarians but also because they present themselves, in ways he understands, as kitsch celebrities, with entourages and prepackaged “looks.”

How to Build a Twenty-first-Century Tyrant

By Adam Gopnik

The New Yorker, May 16, 2022

Today’s autocrats tend to have a changing rather than a fixed series of villains. Anti-Semitism was always central to Hitler’s world view. Stalin, too, was a man of cemented antipathies. As the historian Simon Sebag Montefiore’s work has shown, Stalin was a genuine Marxist intellectual who believed in class warfare and the evils of the bourgeoisie as much as any student at the Sorbonne. By contrast, Berlusconi and Erdoğan and Orbán and the rest are essentially opportunists of hatred; one day their villain is the multinational corporation and the next it’s socialism. Cosmopolitan liberalism is their chief hatred, but they draw it as a monster of many faces. In general, there’s an overt quality to the new authoritarians, cynicism turned into irresistible candor. With them, what you see, and what they say, is what you get.

Lives of the Tyrants

Mussolini: The New Romulus and the New Rome

By B.H. Liddell Hart

The Atlantic, July 1928

“His sparse hours of leisure and repose are spent during the winter in a small, simple apartment in an old palace on one of Rome’s side streets. Here his equally simple wants are attended to by a single servant, a middle-aged housekeeper, and here also he snatches stray hours for his one recreation, other than riding—that of violin playing. On this instrument he is no mean performer. His wife and children still live in Milan, although they come to Rome for periodical visits. For all his cares as father of a greater family, Signor Mussolini makes opportunity to follow closely and keenly the development of his own offspring…

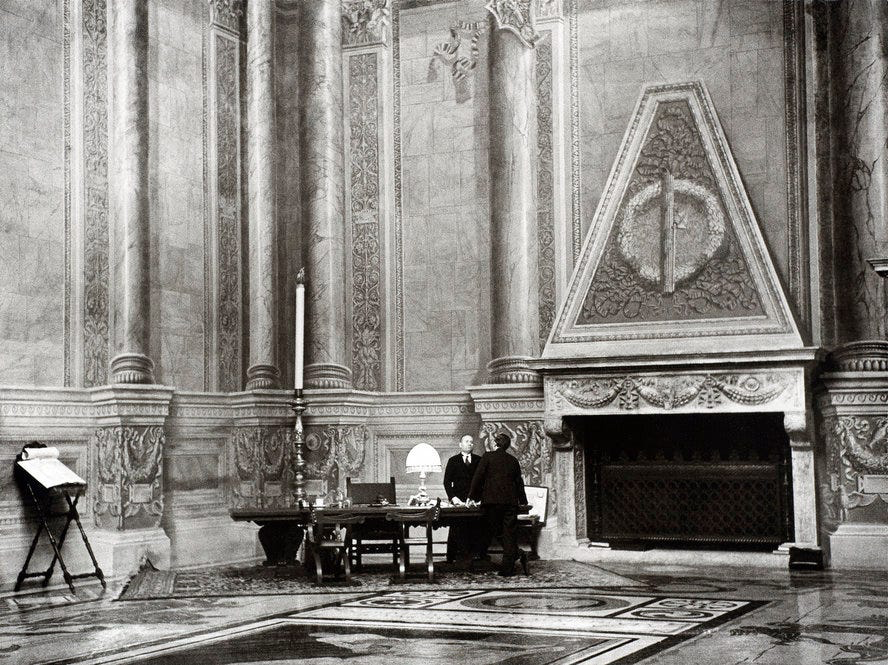

At the Chigi Palace itself the outward trappings of power are not in greater evidence. Entering from the Corso, the visitor meets a solitary doorkeeper in the gateway, sees a cluster of cars in the inner courtyard, and perhaps catches a glimpse of an unobtrusive but watchful plain-clothes man. Thence, unattended, he proceeds up a flight of marble stairs to a spacious anteroom, to be conducted through two more, with a dwindling number of people waiting in each, and finally, relieved of hat and coat, through an inner lobby into the Duce’s room. A vast tapestry-hung chamber, relatively bare of furniture, save for a statue of Victory in the centre. The door by which one enters is at a corner of the room, and diagonally across, at the far corner, is Signor Mussolini’s desk, a model of orderliness. Significantly, behind and above his chair is a bust of Julius Cæsar, and on the desk lies a heavy, finely wrought Egyptian chain, given him for luck by an admire

Hitler: Fuhrer I

By Janet Flanner

The New Yorker, February 21, 1936

Dictator of a nation devoted to splendid sausages, cigars, beer, and babies, Adolf Hitler is a vegetarian, teetotaller, nonsmoker, and celibate. He was a small-boned baby and was tubercular in his teens. He says that as a youth he was already considered an eccentric. In the war, he was wounded twice and almost blinded by mustard gas. Like many partial invalids, he has compensated for his debilities by developing a violent will and exercising strong opinions. Limited by physical temperament, trained in poverty, organically costive, he has become the dietetic survivor of his poor health…

Herr Hitler, by reason of his high offices, occupies the building in the Wilhelmstrasse in Berlin which was called the Reichskanzlerpalais until recently the Nazi government, to avoid any monarchical implications, renamed it the Haus des Reichkanzlers. Devoid of appetite for luxury, he inhabits the palace in agitated simplicity. His physical wants a few; he dislikes servants, and maintains only a skeleton domestic staff of five. Four of them are friendly, political comrades of earlier days who now serve him as chauffeur, chef, major-domo, and aide-de-camp…

In redecorating the Berlin chancellery palace for his use, Hitler’s artistic ameliorations consisted mostly of a few daily modernistic rooms, plus some Nordic mythological tapestries for the Great Hall which depict Wotan Creating the World.

Stalin: Man of the Year

Time, January 1, 1940

Joseph Stalin has gone a long way toward deifying himself while alive. No flattery is too transparent, no compliment too broad for him. He became the fountain of all Socialist wisdom, the uncontradictable interpreter of the Marxist gospel.

His dry doctrinal history of the Communist Party is a best-seller in Russia, just as Hitler's turgid but more interesting Mein Kampfoutsells all secular volumes in Germany. He goes in for Nazi-like plebiscites. Hitler won his 1938 election by 99.08% of the voters; Stalin polls 115% in his own Moscow bailiwick. Stalin's photograph became the icon of the new State, whose religion is Communism.

But Joseph Stalin is not given to oratorical pyrotechnics. Only two or three times a year does he appear on the parapet of Lenin's tomb in Red Square, wearing his flat military cap, his military tunic, his high Russian boots. He attends Party meetings but rarely public gatherings. He has made only one radio speech and is not likely to make many more. His thick Georgian accent sounds strange to Russia.

His life is mostly spent inside the foreboding walls of that collection of churches, palaces and barracks in Moscow called the Kremlin. His office is large and plain, decorated only by the pictures of Marx and Engels and a death mask in white plaster of Lenin. His private apartment, once the dwelling of the Kremlin's military commander, is only three rooms big.

Mao, at 70, Tries A ‘Big Leap’ in the World

Richard Hughes

New York Times, February 2, 1964,

He is, as he himself would be proud to proclaim, a typical tough Chinese peasant, and his stamina and durability, after a life of hardship, exposure and battle, remain formidable. Even if his gay splashing across the Yang‐tse, inside a devoted circle of lifesavers, is now gone with the yellow wind, the intense ferocity and driving dedication of his challenge to the Moscow “revisionists” will doubtless help to keep the flame of life burning…

He has become more and more of a recluse, staying close to his apartment inside the rose‐red walls of the Forbidden City. He still receives very important visitors—very much in the imperial manner—and presides at Politburo meetings. But he spends most of his time at his cluttered desk...

He avoids long speeches now, even at ceremonial occasions. One theory is that, as a voracious chain‐smoker, he is subject to prolonged fits of coughing if he speaks loudly. His voice, it is asserted, has never been recorded. At home, he is indeed the Great Silent Face.

-

Incredible. It really is just like you took excerpts from one single piece and occasionally switched names.

Add a comment: