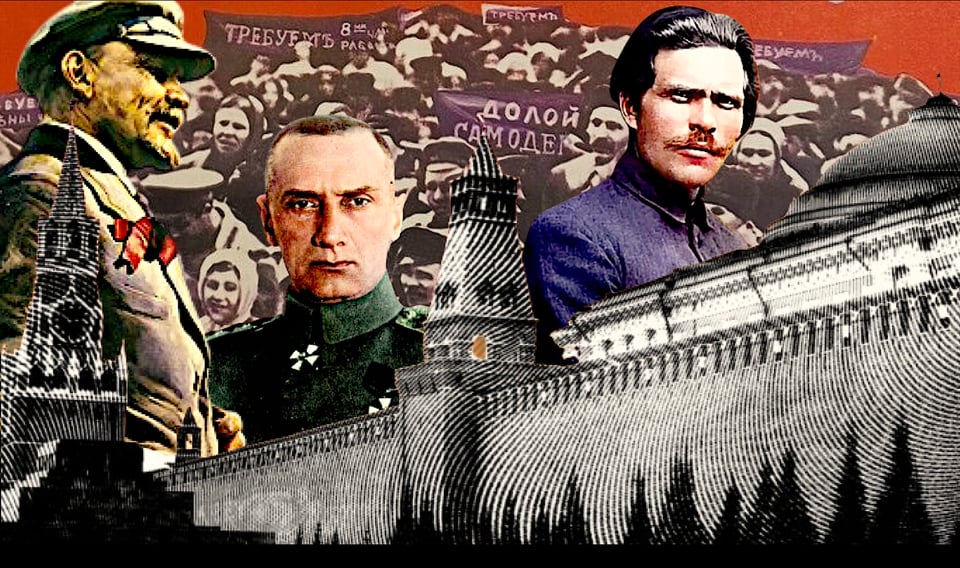

Children of the Revolution

Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers.

Want to read the full issue?

Welcome back to Culture Club, a feature where David and I write about what we’ve been reading, watching, playing, and listening to, for paid subscribers.