Anatomy of a Pogrom

How does ethnic violence start, and how does it spread? Who uses it, and for what purpose?

The past few weeks have provided an object lesson in the durability and utility of blood libel in the United States, as first vice-presidential candidate JD Vance and then his oleaginous boss promoted a baseless lie about Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, eating cats and dogs. That the story was false in the first place—hearsay sourced from a Facebook post about third-hand rumor and denied by city authorities—was never particularly important.

In recent weeks a hateful jacquerie has been inflamed by the far-right media, particularly since Trump repeated his dark fantasy in a debate watched by 67 million Americans. The fact-check was swift, but irrelevant: the existence of the lie, its provocative quality, mattered far more than the particularities or truth of the matter. As Vance told CNN this weekend, defending his continual spraying of the body politic with this shit, “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do.”

In other words: the details don’t matter—hence the proliferation of AI slop memes of Donald Trump riding a cat into battle while wielding an AK-47, the widespread adoption of kitten posters by such pustulous figures as Ted Cruz. The story was always the point, and it’s always the same story: they—whoever “they” are—are not like us, they are inferior, and they demonstrate that inferiority through violence. (This was illustrated quite piquantly by the National Review’s editor-in-chief Rich Lowry, who, in a discussion of Haitians in Springfield, used a racial slur while discussing the false animal-eating stories.)

We have names for this kind of deliberately seeded provocation, whose particulars matter not in their truth but in their form: the sinister picture of a disfavored outgroup—in this case the roughly twenty thousand Haitians living in Springfield’s environs, engaging in grotesque acts of violence—in clandestine gatherings for the purposes of perverse pleasure.

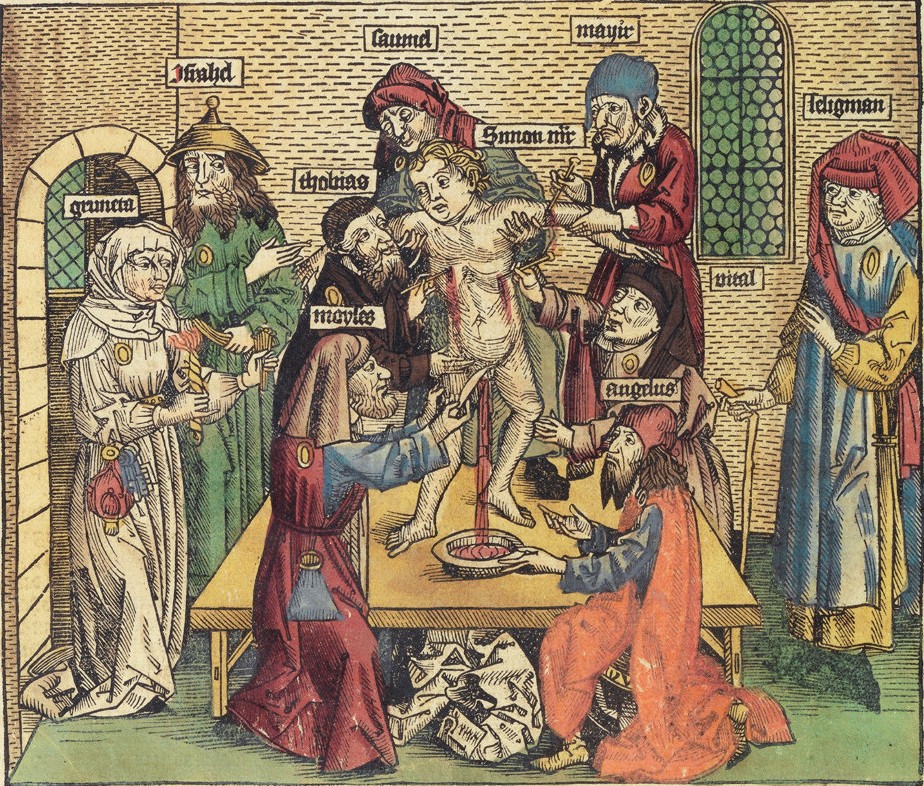

One is the term “blood libel” (blut-bilbul in Yiddish), most closely associated with Christians accusing Jews of murdering innocent Christian children. This millennium-spanning myth is often married with a religious perversion of some sort—from early 1100s accounts of Jews drinking the blood of Christian children in a satanic inversion of the eucharist, to the subsequent, and more durable, myth of baking blood into Passover matzoh (which anyone who has eaten matzoh at any point can attest is false).

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Another term, more broadly applicable in this and other cases, was coined by the historian Norman Cohn as the “nocturnal ritual fantasy,” a typology of thought that he traces from the second century BC onward in the West. "The essence of the society was that there existed, somewhere in the midst of the great society, another society, small and clandestine, which not only threatened the existence of the great society but was also addicted to practices which were felt to be wholly abominable, in the literal sense of anti-human," Cohn wrote. It was employed by Romans against Christians, by Christians against witches, by Catholics against Protestants and vice versa, and, always, by Christians against Jews.

In this contemporary instance, the blood libel employed against Haitians involves not the slaughter of children, but a different incursion into white domesticity—the kidnapping, ritual butchering and consumption of household pets. As Chaucer wrote of the Jews in The Prioress’s Tale: “A murderer they found, and thereto hired/Who in an alley had a hiding-place;/And as the child went by at sober pace/This cursed Jew did seize and hold him fast/And cut his throat, and in a pit him cast.” The secrecy of the violence is the essence of its sinister nature.

The Springfield blood libel is an appeal to sentiment and to disgust, and an overt incitement to violence. Over the past two weeks, according to Ohio governor Mike DeWine, at least 33 bomb threats have been called in—to local hospitals, to college campuses, to aid organizations—prompting daily police sweeps of the town’s schools. On Monday, the Ohio state house was placed on lockdown following a bomb threat. Proud Boys and Blood Tribe members have marched through the city; the Ohio Klan have distributed fliers capitalizing on the lie, calling Haitians “beasts of the field.” All of this is part of the same story, the same threat: you have harbored those we find abominable, about whom we have told a violent lie, and we will follow our imagined violence with real violence.

There are many motivations for a meretricious campaign of this kind: distraction (in the case of tsarist autocracy seeking to dispel discontent, for example, or to draw attention away from flagging poll numbers); greed; the desire to shift and displace blame for economic or social conditions. None of these explanations are exculpatory. To create a blood libel is to invite violence. There is no other consequence. To wield this sort of calumny is to ready the ground for the destruction of innocents, and there is no escaping the moral stain of its promulgation.

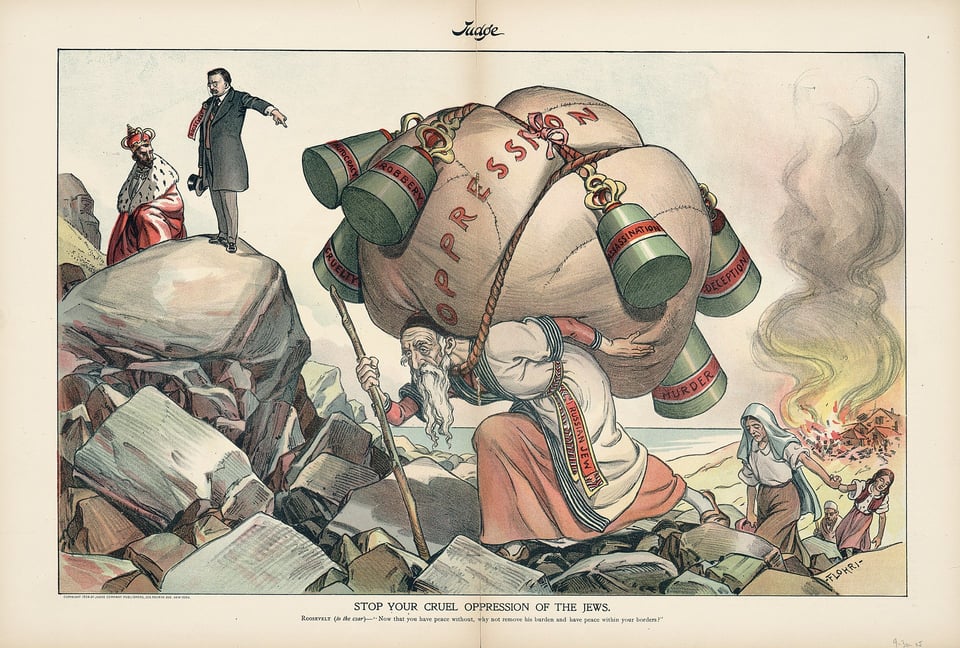

A third term for this evil is “pogrom”, which itself comes from the Russian verb pogromit—to destroy through violence—and its root, grom, is “thunder.” The terrifying crack precedes the catastrophe. The lie booms before the strike. This was the case in Kishinev over a century ago, in a pogrom that drew worldwide condemnation, and resulted in the widespread introduction of the word “pogrom” into English. Some fifty Jews were murdered, Jewish women were raped en masse, and roughly 1,500 homes were destroyed. It was Easter Sunday, April, 1903. In February of that year, the popular newspaper Bessarabetz, led by rabidly antisemitic publisher Pavel Krushevan, reported that two Christian children—a Ukrainian boy and a Christian girl who died in a Jewish hospital—had been murdered by Jews for the ritual use of their blood. The thunder took a time to roll over the city, but by the time of the Easter celebrations, the rumbling built to a bloody downpour.

There are many Pavel Krushevans in America right now. And just as many who will happily watch what unfolds as a result of these vile and familiar stirrings: those who, in one account of the Kishinev pogrom, gawked and spectated. According to the account in Yehudei Kishinev: “The streets filled with broken furniture and feathers from the bedding. The rest of the curious population among them intellectuals, priests, clerks, seminary students, old people, women and children did not stay idle; they participated to the ‘cleaning of the streets’ and ‘picked up’ all that was valuable. They robbed the jewelry, clothing and shoes and everything they could grab. The authorities cared that the mobs be entertained and ordered the military band to play in the centre of the city as usual and disregarded what was happening a few meters away.”

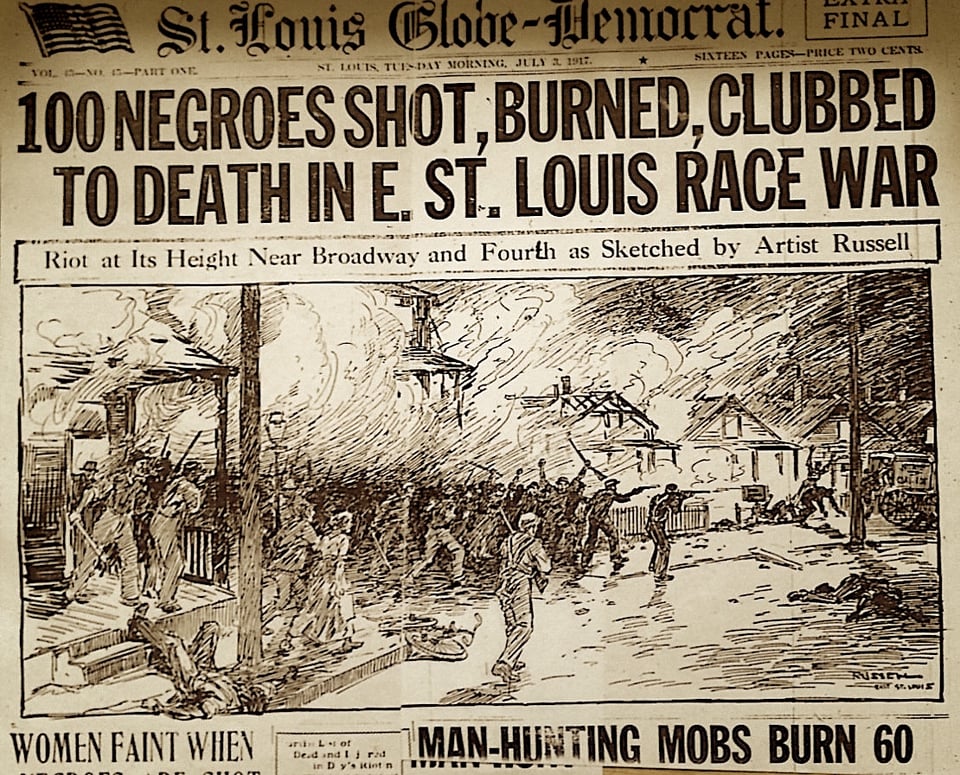

By 1917, the concept of the pogrom had become widely applied to the American habit of sudden and violent racist attacks. That year, the East St. Louis massacre—a race riot in which white men poured into African-American neighborhoods, murdering hundreds and burning homes—offered a picture of an American pogrom. Like the current odium against Haitians, the East St. Louis massacre was prompted by the movement of people, migrants who had come north seeking factory jobs in the booming war economy of the Great Migration. A shifting economic landscape, and a racist lie—in this case the familiar one that Black men were fraternizing with white women in clandestine unions (a form of “abominable” behavior in that moment, and a signature example of the role sexual paranoia has always played in American racism).

Later that year, the Yiddish Forverts, in New York, called Kishinev and St. Louis “twin sisters.” United by pogrom, and its consistent anatomy: the drumroll of the lie, the buildup of pressure, the storm. It is happening now, that terrible static electricity, the boots on the march like a hard rain. Only through a relentless solidarity—as strong as a wind to sweep thunderheads away—can we keep this well-known and relentless beat at bay, avoid being sisters of the storm, and instead earth and disperse its cruel lightning.

Add a comment: