Abortion, Underground

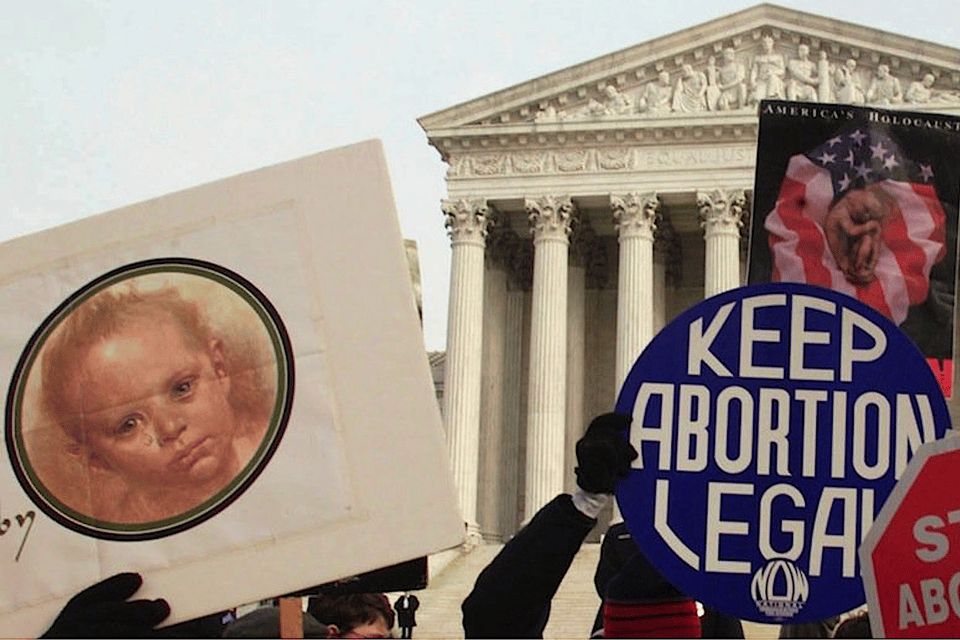

Yesterday saw the shambolic and somewhat parodic Iowa caucuses; despite the lavish media attention devoted to candidates with minuscule percentages of the Republican vote, it was Trump, as it was always going to be. Knowing his allies and their goals, it was also another step towards something that once would have been unthinkable, and now has a stench of the inevitable about it: a national abortion ban. I grew up under the protective shadow of Roe; blinking in the harsh light of its dismantling, the landscape is bleak, bans cropping up everywhere, and everywhere women dying.

But women don’t stop terminating their pregnancies when abortion is made illegal.

There are instructions for abortifacient herbs, and methods dating back to the earliest written records; the “illegal operation,” as it was euphemistically termed in pre-Roe America, is also one of the most consistent and necessary medical interventions in the history of reproduction, which is the history of humanity. There are always—and have always been—times when women cannot bear a child: times of hunger, times of war, times of privation and want; times when a woman is physically unable or mentally unable or socially unable to bear a child. There always will be, and always have been, times and situations where the needs of the grown and born woman supersede those of the bundle of cells in her womb.

As abortion is banned at progressively earlier points in the pregnancy in more and more states, and women are being prosecuted under these laws, the once-again “illegal operation” has returned to the underground. Legitimate medicine is either forced to cooperate or eagerly cooperates with state enforcement; in a recent, hideous prosecution of an Ohio woman for having a miscarriage at home after being denied proper medical care, she was turned in by a nurse. Catholic hospitals stand at the center of a wildly spiraling maternal mortality rate. In lieu of these doctors, either fearful or zealous, people seeking abortions have to turn elsewhere—if they have anywhere to turn at all.

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with a paid subscription.

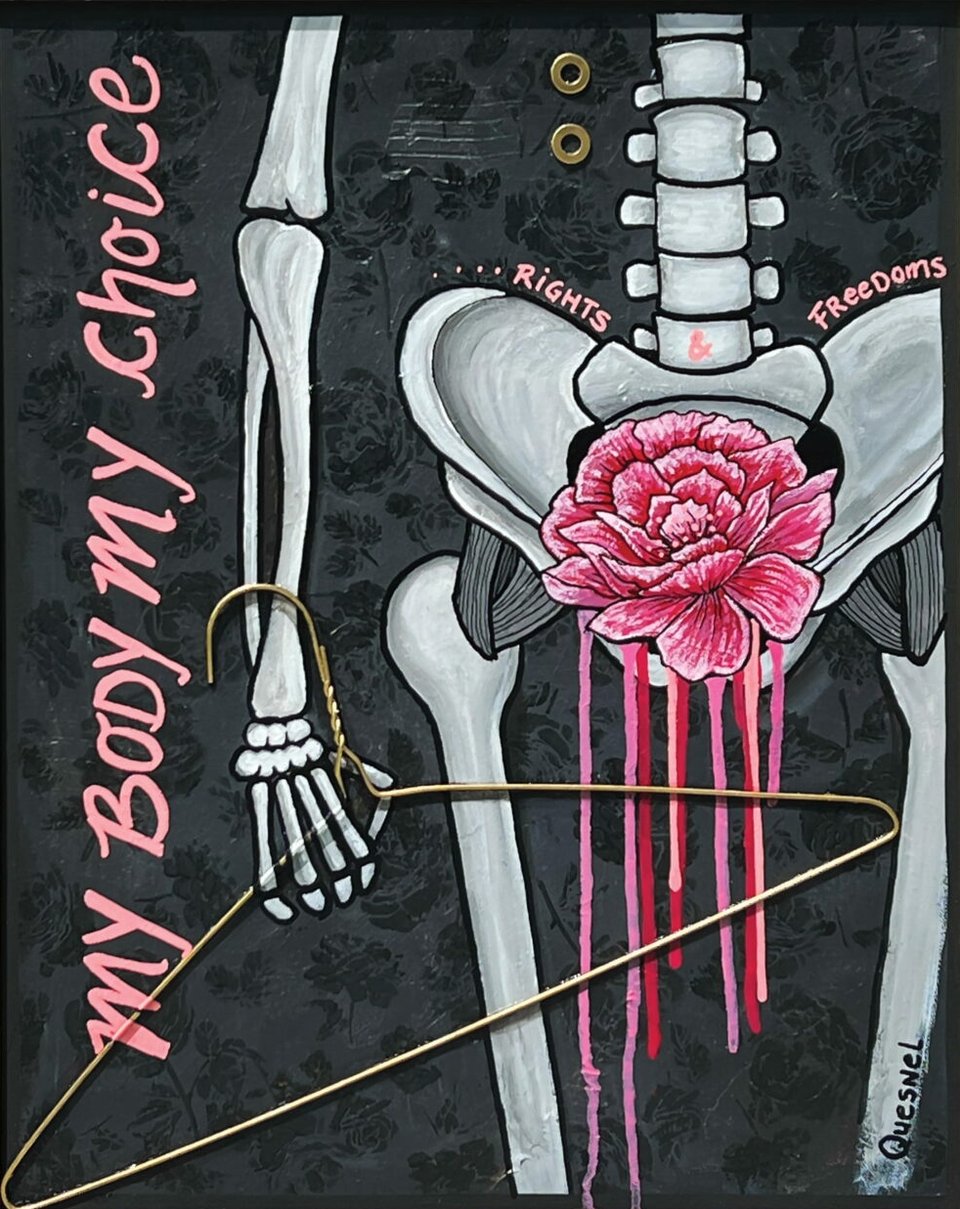

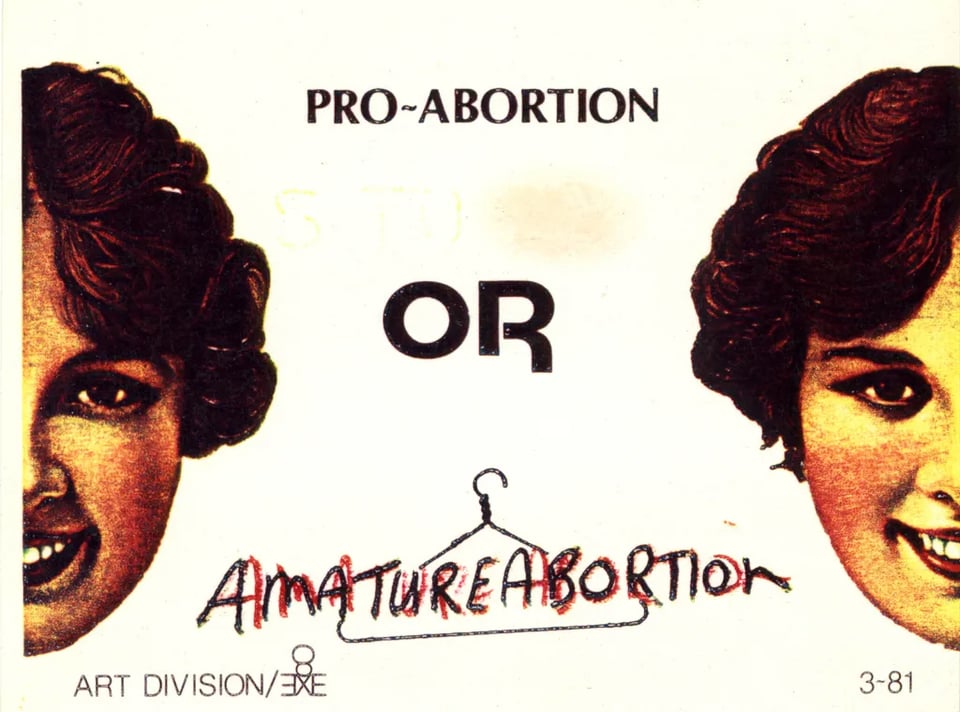

The “back-alley” abortions and self-induced abortions that made coat hangers a feminist symbol loom over the mid-twentieth century, grim relics of a bad past dragged from the grave by legislative zealotry. In power today are people who believe a woman’s chief role, should her life be imperiled by a fetus, is to die a martyr—like the Catholic saints who suffered, like the Protestants in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, a staple of many evangelical childhoods—and that such a death is meet, just, even sacred. (Abortion was initially made illegal in the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century, by the newly-minted, all-male American Medical Association, which sought economic benefit from the bans: they squeezed midwives out of the economy, made doctors in charge of all obstetrics, though their mortality rates were significantly higher than those of midwives. See below for more.)

In the interim, certain technological developments—chiefly abortion pills, misopristol and mifepristone—have made illegal abortion access easier and safer, even if women are still being prosecuted for accessing treatment. There are many people who have reacted to the past decade’s surging spate of restrictions by learning the techniques of dilation and curettage themselves, or the cannula, trained by others with knowledge of the art. Still, in the gray ground in which pregnant women find themselves in much of the States (and perhaps all, depending on which way the election goes), there is ample room for both the generous and pure of spirit—like the feminist Jane Collective of the twentieth century, who presided over safe illegal abortions, risking themselves for the safety and sanity of others–and for those who are not so well-intentioned.

By pushing abortion underground, into the murk, women, and particularly those without resources—meaning, inevitably, women of color and immigrant women and poor women—can find themselves preyed upon brutally, in ways they cannot report to authorities. Back at the fin de siecle, notorious serial killer H.H. Holmes used abortion as a pretext to lure several of his victims to their deaths. In the 1963 novel The Expendable Man, by Dorothy Hughes, the abortionist Doc Jopher is a drunk, stripped of his medical license, who performs abortions on his “battered couch” while actively intoxicated; his is, Hughes says, a “butcher’s business.” Tens of thousands of women died in the American midcentury of botched or self-induced abortions, and those who did not die faced prosecution. In the sources below, we’ve gathered the stories of women caught in the abortion underground, in an effort to demonstrate why this malediction will not stop abortion—only create more needless death.

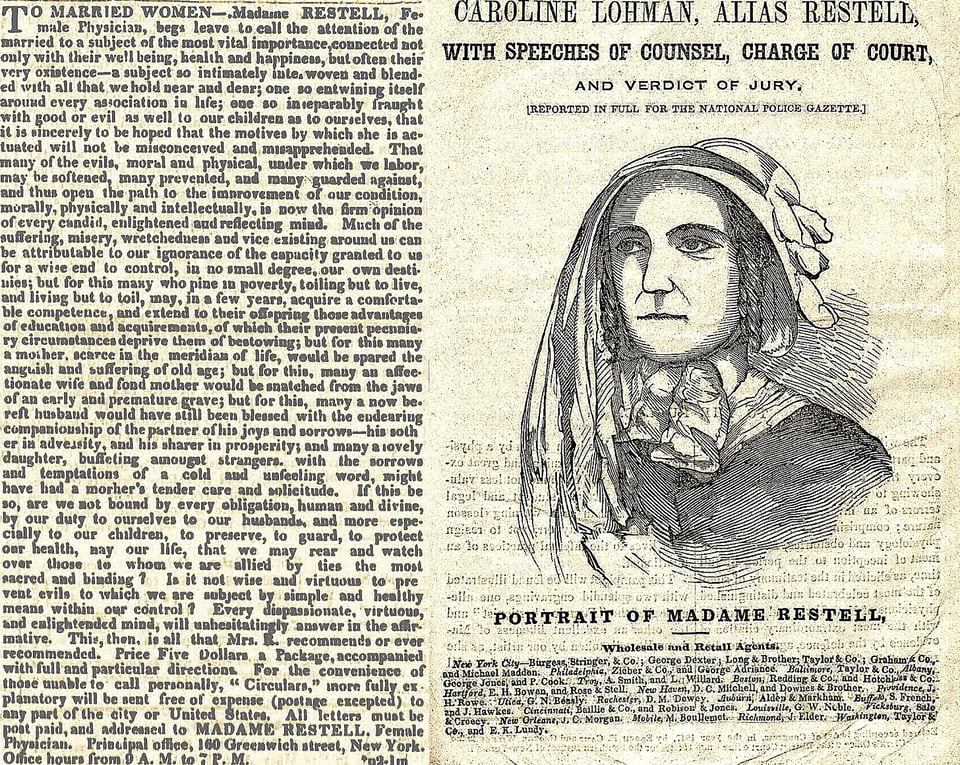

The Notorious Madam Restell

By Robert Sneddon

The New Yorker, November 15, 1941

Madam Restell’s maiden name was Ann Trow. The facts of her origin are somewhat obscure, but it is probable that she was born in England, in a Gloucestershire village, in 1812. (To the end of her days, in spite of the veneer of culture which she eventually acquired, she dropped her “h”s in moments of excitement.) Her family was poor, and she was shipped off to London to be a serving maid in a wealthy butcher’s house. Then, while she was still in her teens, she married a journeyman tailor named Henry Somers, who was afflicted with wanderlust and a liking for strong drink. When Ann was nineteen, she and her husband came to New York; two years later he died of excessive drinking, leaving her and an infant daughter penniless. The young widow was not long in finding a way to support herself and the child. The story goes that her room on Chatham Street (now Park Row) was near the shop of a friendly herbalist, who taught her some useful secrets. Perhaps, as Madam Restell later claimed, they were taught her by her grandmother in England. At any rate, she was soon started on the career that was to win for her the title of the wickedest woman in New York.

The Abortionist on the Circuit of Fear

By Marlene Nadle

The Village Voice, August 18, 1966

It is because of the ever present risk which increases as the skill of the abortionist decreases that Rappaport wants even the best of illegal abortionists put out of business by hospitals given the freedom to deal realistically with abortions and the determined women who insist on having them.

Ideally, he would like to do away with all laws limiting hospital abortions because he considers these laws no more relevant or necessary to a medical problem than laws dictating tonsillectomies.

Practically, he wants the laws in this country liberalized at least to the Swedish or Danish level. And maybe even to see abortions covered by Blue Cross.

Abortion Comes Out of the Shadows

LIFE, February 27, 1970

Women who can afford it flee the country, seeking legal abortions in Japan, Mexico and Puerto Rico. Recent English reform has made London particularly popular, partly because it seems less "foreign."

Those who stay at home find it is possible to get an illegal abortion in virtually any sizable city in the U.S. Many of these operations are performed by competent doctors in antiseptic quarters, often in undercover clinics operated specifically for that purpose. The fee varies from $200 to $1,500 or more, often depending on the patient's ability to pay. For these doctors, the risk is high: performing an illegal abortion is a felony in most states and a conviction can cost a physician his license. Still, many physicians find themselves unable to turn down requests. "If a girl is determined to end her pregnancy,” says an Ohio doctor who has performed 500 abortions, "she may as well survive."

For in the desperate, emotionally charged search for an abortionist, hundreds of thousands of girls find their way to quacks and charlatans who are the frightening models of abortion folklore. Some women attempt the job themselves. Last year 350,000 women needed hospital care after botched abortion attempts.

More than 8,000 of them died.

Abortion in Texas

By Martha Hume

Texas Monthly, March 1974

"I was raped. I guess it was my own fault in a way, but I was passed out when it happened. It was my first time and I didn't even know what was happening. I still feel bad about that…

"My brother told my parents and they took me to a doctor who said the baby would be deformed. My father took me to a place in Mexico City. It was really insane. We had to go from one hotel to another and they picked us up on a street corner in this big car. They tried to induce a miscarriage but it still wouldn't work.

"What was supposed to be a two-day stay ended up being two weeks. I finally miscarried naturally.

"I was screwed up for two years after that. I had a nervous breakdown. I was taking drugs—speed and the whole bit. I'm all right now, but it's taken a long time."

On Abortion

By Ellen Willis

The Village Voice, March 5, 1979

We live in a society that defines child rearing as the mother’s job; a society in which most women are denied access to work that pays enough to support a family, child-care facilities they can afford, or any relief from the constant, daily burdens of motherhood; a society that forces mothers into dependence on marriage or welfare, and often into permanent poverty; a society that is actively hostile to women’s ambitions for a better life. Under these conditions, the unwillingly pregnant woman faces a terrifying loss of control over her fate. Even if she chooses to give up the baby, unwanted pregnancy is in itself a serious trauma. There is no way a pregnant woman can passively let the fetus live; she must create and nurture it with her own body, in a symbiosis that is often difficult, sometimes dangerous, always uniquely intimate. However gratifying pregnancy may be to a woman who desires it, for the unwilling it is literally an invasion—the closest analogy is to the difference between lovemaking and rape. Nor is there such a thing as foolproof contraception. Clearly, abortion is by normal standards an act of self-defense.

The Morning After

By Brett Harvey

Mother Jones, May 1989

In the late 1960s up to 1.2 million illegal abortions took place each year, and that at least five thousand women a year died from criminal abortions. But these are abstractions unless you lived through them. It's hard for today's young women to imagine abortions in dark, dirty rooms that smelled of Clorox, done by doctors who breathed bourbon fumes and copped a feel before they got to work, and warned you not to scream or they'd walk out and leave you alone in the middle of nowhere. Or self-aborting alone in your college dorm room, scared to tell anyone, watching your metal wastebasket fill up with blood, flushing the fetus down the toilet, terrified that it would clog the plumbing and you'd be found out. Or being rushed to the hospital hemorrhaging from a perforated uterus, only to be interrogated by police officers demanding to know where you got the abortion. But that's just the dramatic stuff. What's even harder to convey to people who haven't experienced it is the fear, the guilt, and the humiliation involved in even an uneventful illegal abortion, or the common experience of having to convince a review board of male doctors that you'd commit suicide if they forced you to have this baby.

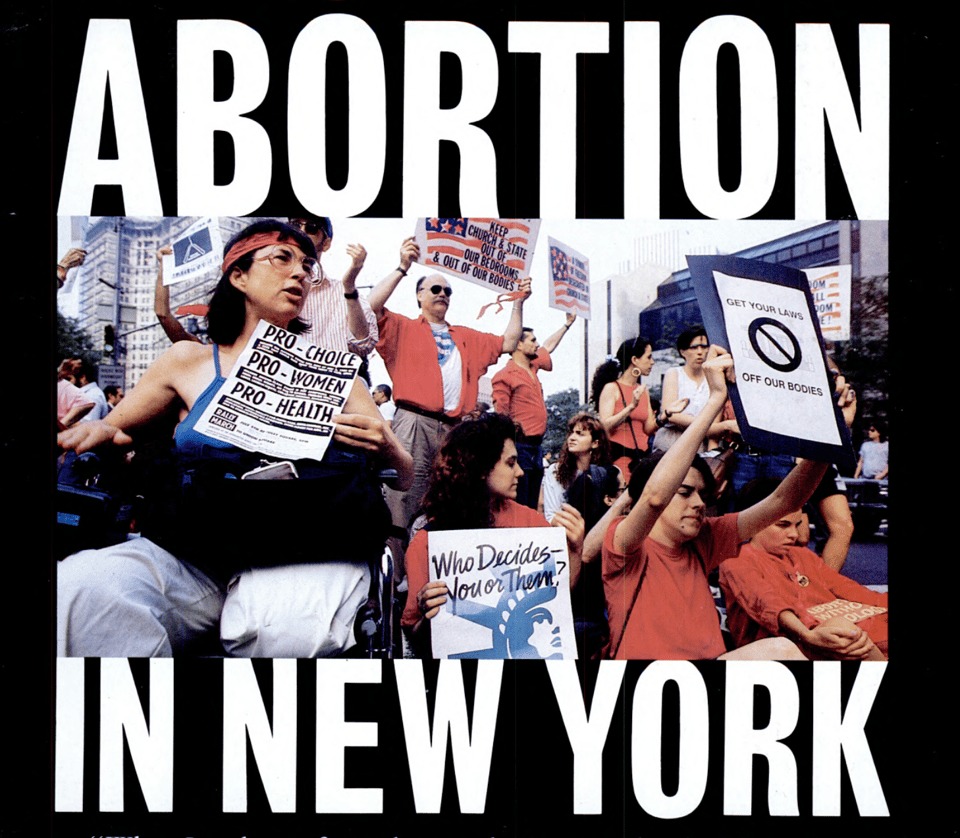

Abortion in New York

By Jeanie Kasindorf

New York, September 18, 1989

"I had an abortion in 1951 on the kitchen table in my boyfriend's apartment in Brooklyn. And if you've ever experienced an illegal abortion, you want to make sure abortion stays legal forever." Evelyn is a 60-year-old counselor at one of the city's largest abortion clinics. "It's a terrible, terrible experience, an illegal abortion; it's designed to make women feel less than a human being. I was living with my parents in Brooklyn at the time I had my abortion. I was 22 and single and working as a secretary in Manhattan. I became involved with a young man about the same age.

"I knew immediately that I would never continue the pregnancy. Just having sex at that time was such a no-no for a single girl. At first it was frightening because I didn't know if I could find someone to do it. I spoke to a girl at work who knew another woman who told me who to call to set it up. I called this man in Brooklyn. He had a foreign accent. He might have been a doctor in his country; I never knew. He said, 'You tell me where to come, and show up with $250.”

Abortion Mills Thriving Behind Secrecy and Fear

By Robert D. McFadden

The New York Times, November 24, 1991

It is a shadowy business, the unregulated world of abortion mills, shabby clinics operating behind the facades of doctors' offices, often in poor neighborhoods. Its victims are women who know little about legal rights or medical options, who have seen an ad or heard a tip and come to this—driven by fear and loneliness or fates beyond invention—to risk butchery on a table.

No one knows how many such fly-by-night surgeries there are in New York City or how many abortions they produce. But law-enforcement officials and medical experts say dozens of these clinics are believed to be tucked away behind storefronts and in more ordinary-looking doctors' offices and they are believed responsible for scores or even hundreds of illegal or incompetent abortions annually.

And beyond the numbers, experts say, lies the suffering of women who seek illegal abortions—those in the last trimester of pregnancy with the mother's life not in danger—or who are victimized by incompetent abortionists because they are poor and uneducated, do not speak English or do not know how to find a good clinic, evaluate medical treatment or file a complaint if things go wrong.

The Abortionist

By Tom Junod

GQ, February 1994

Doc lost one once. A young woman, college aged. On the poster John Burt made of him, advertising his sins, there is this information: "Britton is directly responsible for the death of at least one woman. [The woman] died... from complications stemming from a SAFE, LEGAL ABORTION performed by Britton. Does Doc remember? Sure he does. How can he forget? "She was sort of a runaway type, living in a crash pad... She had a double uterus, so there were complications... I couldn't stop the procedure; I had already broken the barrier, and it was improper to quit... She started vomiting a day after. She went to the emergency room—maybe she had haphazard treatment, maybe she stayed at home too long—but she did get admitted. She was in shock. She was sick. I tried to get through to the doctors, to tell them what I knew, but they wouldn't talk to me. They treated me like a criminal! Like talking to me would taint them! They ended up operating on her and she died after surgery. But why operate? They did it to prove I did something wrong! They took out her uterus, but they didn't treat the girl. If they had treated her shock, she'd still be alive.

The Rise of DIY Abortions

By Ada Calhoun

The New Republic, December 2012

Techniques for terminating a pregnancy can be found in the Bible, on Egyptian papyrus, and in Chinese records dating to around 500 B.C. There are too many to list, but women have attempted home abortions with mercury, quinine, pennyroyal, iron sulfates, and a mixture of camel saliva and deer hair; Hippocrates once advised a prostitute to jump up and down.

Before Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in 1973, American women inserted knitting needles and other sharp objects into their cervixes to end unwanted pregnancies. They put dangerous drugs like the tissue-destroying potassium permanganate into their vaginas, which typically failed to terminate pregnancy but sometimes caused hemorrhage. Elihu Sussman, a retired New York City pediatrician who was working as a medical student at Boston City Hospital in the 1960s, says, “There were thirty beds, and some of them were always filled with women who came in because of septic abortions—four, five, six at any given time.” His wife, Geraldine Sussman, was a student nurse at Bellevue in New York during the same period. “They’d use coat hangers, laundry detergent products,” she says. “A lot of them would rupture their uteruses and end up with hysterectomies. People now don’t realize what it was like. It was awful.”

“Whatever’s Your Darkest Question, You Can Ask Me.”

By Lizzie Presser

California Sunday Magazine, March 28, 2018

After the American Medical Association formed in the 1840s, it launched a campaign to make abortion illegal at all stages of pregnancy. The AMA’s campaign painted abortion as immoral, and by 1880, it secured criminal abortion laws in nearly every state, granting doctors the authority to decide when the procedure was acceptable. The effort grew, in part, out of physicians’ interest in limiting competition from midwives and homeopaths. Pregnant women, especially the poor, continued to seek the care of midwives, many of whom were immigrants and women of color; medical journals began referring to midwives as abortionists, describing them as dangerous and ignorant. Although studies established that midwives had better maternal mortality outcomes than physicians in the early 20th century, the overwhelmingly male AMA almost succeeded in driving them out. States began writing new laws restricting midwifery, and the share of births that midwives attended dropped from half in 1900 to 15 percent by 1930.

The Criminalization of the American Midwife

By Jennifer Block

Longform, March 10, 2020

The story of the outlaw midwife begins... with patriarchy and the church and colonialism; in the United States it begins in the 1800s, when the white, male profession of medicine claimed authority over what today we call health care, and midwives were an obstacle. They were also an easy target—the majority were immigrant, Indigenous, and black women. At first states outlawed abortion partly as a means of limiting midwives’ practice. Then state after state erected statutory barriers for midwives, first by licensing and supervising existing midwives and later by denying licenses in all but a handful of states, so that by the 1960s hardly any midwives existed in North America. “The question was not whether midwives should disappear but how rapidly,” wrote historians Dorothy and Richard Wertz.

Doctors swiftly transformed childbirth from something women did in upright positions with social, skilled support to something doctors did to them with medical technology, though what happened was far from what today we would call evidence-based medicine. By the 1920s, the majority of laboring women were isolated in hospital wards and given morphine and scopolamine, an amnesiac.

Caught in the Net

By Leslie J. Reagan

Slate, September 10, 2021

The doctor’s examination in search for evidence required each woman to remove her clothing, spread her legs, and allow the doctor to touch and look at her genitals, and physically invade her vagina with a medical instrument—a cold speculum—through which he viewed her cervix and uterus. In the name of collecting evidence of a crime, the doctor performed a coercive exam. And even if he was polite and kind, these were humiliating, voyeuristic, and frightening procedures performed not for the benefit of the woman, but for the police. Prenatal care and annual gynecological exams included pelvic exams, but at that time, many patients found them uncomfortable and avoided them in order to avoid exposure and embarrassment. We can imagine the horror of captured women forced to undergo such exams. We also now know that such exams can be particularly traumatizing for people who have been sexually abused.

Of Course They Want Us Dead

By Jessica Valenti

Abortion Every Day, January 3, 2024

How many more ways can they make it clear that they want us dead? And I mean that literally. As I wrote in 2022, it’s not just that Republican lawmakers and the anti-abortion movement see women dying as an unfortunate but acceptable consequence of making abortion illegal. To them, the most noble thing a pregnant woman can do is die so that a fetus can live.

There’s a reason that anti-choice groups have spent the last year and a half valorizing pregnant women who decline cancer treatment or other medical care. In part, they’re spreading these stories because they know maternal death rates are rising in the wake of Roe’s demise—they want to turn horror stories into martyrdom success stories. They need to make our deaths more palatable.

Add a comment: