A Golden Age of Conclaves

By David Swanson

The term conclave dates back to the 1268 papal election in Viterbo, Italy, which lasted so long that the fed-up townspeople locked the cardinals away with a key—“cum clave”—reduced their meals to one a day, and removed the roof of the papal palace until a decision was reached. Altogether, it still took three years. (To ensure that never happened again, the rules of the modern conclave were enacted for subsequent elections.) In total, nineteen cardinals convened in 1268; at this week’s conclave, 135 will be locked away, 108 of whom were appointed by Pope Francis. How those cardinals will act behind closed doors will remain a mystery to outsiders, and that’s the whole point. But, as anyone who watched last year’s lush, Oscar-nominated drama “Conclave” should recognize, there is still room for corruption and campaigning, power grabs, and politicking. We just won’t see it.

I’ve long been fascinated by the politics of the papacy, and conclaves in particular. So, as Francis’s health deteriorated this winter, I began to read and watch everything I could get my hands on. In just the last few months, in addition to “Conclave”, I’ve watched “The Conclave” from 2006, about the 1458 papal election. I’ve done a rewatch of “Borgia: Faith and Fear”, which devotes more than two hours to the 1492 conclave. I’ve read Behind Locked Doors: A History of the Papal Elections by Frederic J. Baumgartner, The Conclave by Michael J. Walsh, The Bad Popes by E.R. Chamberlain, and Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy by John Julius Norwich. To be perfectly honest, I may not have read all of them cover to cover; my focus was on the renaissance papacy, because renaissance Italy is my version of Talia’s preoccupation with polar exploration. I’m obsessed.

History always holds up a mirror to the past, and in the often-sordid struggles over the papacy, I see reflected many of the elements muddying the world of contemporary politics. There’s greed, nepotism, corruption, propaganda, sex scandals, conspiracy—despite the holy trappings, the whole era is as venal a lesson in realpolitik as anyone this side of Machiavelli could hope for. This may pertain more to the secular sphere than the ecclesiastical—although who knows what happens behind locked doors?—but a conclave is always the site of varied, clashing, complex interests. And it draws me in like a pilgrim to a sacred shrine.

Ahead of Francis’s death, I spoke with Dr. Ada Palmer, whose terrific new history, Inventing the Renaissance: Myths of a Golden Age, was published in March. “History can help us show what is unique right now,” she told me. Throughout the book—which manages the delicate task of being both dauntingly exhaustive (it’s over 700 pages) and breezily conversational (perfect for audiobook-philes)—Palmer draws parallels between the rise of the imperial papacy and the turbulent politics of today. She also runs a mock conclave with her students at the University of Chicago every year, recreating the 1492 papal election.

“Even the most powerful people don’t actually manage to control things enough to get the outcome they want,” she told the New York Times this week, talking about the lessons of the conclave. “And even the least powerful people, when they work at it, can affect and influence what happens in the end.” To help get a better sense of the history behind this week’s proceedings—and, inter alia, experience the peculiar pleasure of seeing the modern world's faults in history's mirror—I decided to look back on five notorious Renaissance conclaves, featuring all manner of Vatican skullduggery.

1410: The Pirate Pope

The renaissance papacy is notorious for reaching depths of depravity unbefitting the “vicar of Christ on earth.” One of the most depraved popes rose up from the chaos of the Papal Schism that lasted from 1378 until 1417. The turbulent state of the Catholic Church was marked by a series of popes and antipopes—one of whom was Baldassare Cossa, a former pirate who was, in the words of historian Johann Peter Kirsch, "utterly worldly-minded, ambitious, crafty, unscrupulous, and immoral, a good soldier but no churchman." In order to overcome this reputation and achieve the papal tiara, Cossa needed to bribe his fellow cardinals, so he turned to a wealthy but provincial Florentine banker named Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici. The cornerstone of the Medici family’s future as the premier princes of the Italian Renaissance was laid with this alliance.

Cossa won the election, though he had to settle for the title of Antipope. As for the Medici, in return for their largesse the family bank was rewarded with the incomparably lucrative papal accounts. Giovanni di Bicci realized that banking was an unstable foundation upon which to build a dynasty, so his heirs used that fortune to consolidate power both in their native Florence, and then beyond. It would take just over a century before Giovanni’s great-great grandson would be crowned as Pope Leo X, and 150 years for another heir to wear the crown of France. At that point the family was more princely than businesslike, their priorities having shifted from profit to political power.

1458: Surreptitious Consultations in Latrines

For most of the 14th century, the papacy had been exiled to Avignon in Provence, and the college of cardinals had grown increasingly cosmopolitan. In fact, it would be many years before the Vatican saw so international a group as that convened at the 1458 conclave. “The eighteen cardinals included eight Italians, five Spaniards, two Frenchmen, two Greeks, and one Portuguese,” writes Frederic Baumgartner in Behind Locked Doors: A History of Papal Elections. “This conclave was the last one until 1958 in which non-Italians constituted a majority of the voters.” Cardinal d’Estouteville was the choice of the French crown, and was considered the most papabile (pope-able) candidate in the college, thanks in no small part to the royal fortune he was prepared to distribute.

“The richer and more powerful members of the college… begged, promised, threatened, and some, shamelessly casting aside all decency, pleaded their own cause and claimed the papacy as their right,” wrote Cardinal Aeneas Piccolomini in his memoirs. “Their rivalry was extraordinary, their energy unbounded. They took no rest by day or sleep by night.” There followed surreptitious consultations in the latrines, simony, fraud, and even fisticuffs. In the end, D'Estouteville’s efforts backfired, and it was the humanist scholar Piccolimini who prevailed, taking the name Pius II. The deciding vote came from 27-year-old Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia.

1492: Rise of the Borgias

Nearly four decades would pass before Borgia’s time as a papabile candidate would come. In many ways the most emblematic of the Renaissance popes, Borgia was nephew of Pope Calixtus III—in fact, in a veritable nepo baby boom, eight of the 23 cardinals in the 1492 conclave could claim a previous pope as uncle. Corruption dominated the proceedings on all sides: Borgia used his considerable fortune to bribe his fellow cardinals with promises of property and ecclesiastical benefices; his rival Giuliano della Rovere, according to Palmer, “came to the conclave with 200,000 gold ducats for bribes supplied by Charles of France and another 100,000 from Genoa ($300 million, likely the most ever spent on a papal election).” In “Borgia”, the European series about the family, the conclave is played like something straight out of “Game of Thrones”. “I think they had three episodes devoted to the actual elections,” says Palmer. “Endless drama! So many factions trying to get so many things. If anyone in Hollywood reads this, talk to me, we could make a whole series.”

The Sword and the Sandwich is a newsletter about deadly serious extremism and serious sandwiches. Please consider supporting this work with

a paid subscription.

Borgia emerged victorious, and spent the next decade dragging the reputation of the Vatican through the mud as he tried to secure his family's power. As Pope Alexander VI, he made his son Juan captain of the papal army, wed his daughter Lucrezia off in a series of upwardly-mobile political marriages, and invoked “an obscure emergency power the pope has to appoint extra cardinals in times of crisis (such as war or surges of heresy)”—including his own son Cesare (who later renounced his cardinal’s hat), and his mistress’s brother, Alessandro Farnese, who would be crowned Pope Paul III in 1534. In total, Alexander created twelve new cardinals in a bid to secure his family’s political legacy.

1503: Give Me a Sword

As subsequent conclaves would show, he Borgias failed in that goal. The death of Alexander VI was followed soon after by that of Cesare, and then by the papacy of his successor, Pius III—who was himself the Piccolomini nephew of Pius II, and who also failed to entrench his family’s power, on account of him dying a mere month after his conclave. This meant the time was finally ripe for Giuliano della Rovere to take the papal throne, three decades after his uncle, Sixtus IV. As Pope Julius II, he immediately moved to solidify his own power, while uprooting his rivals’.

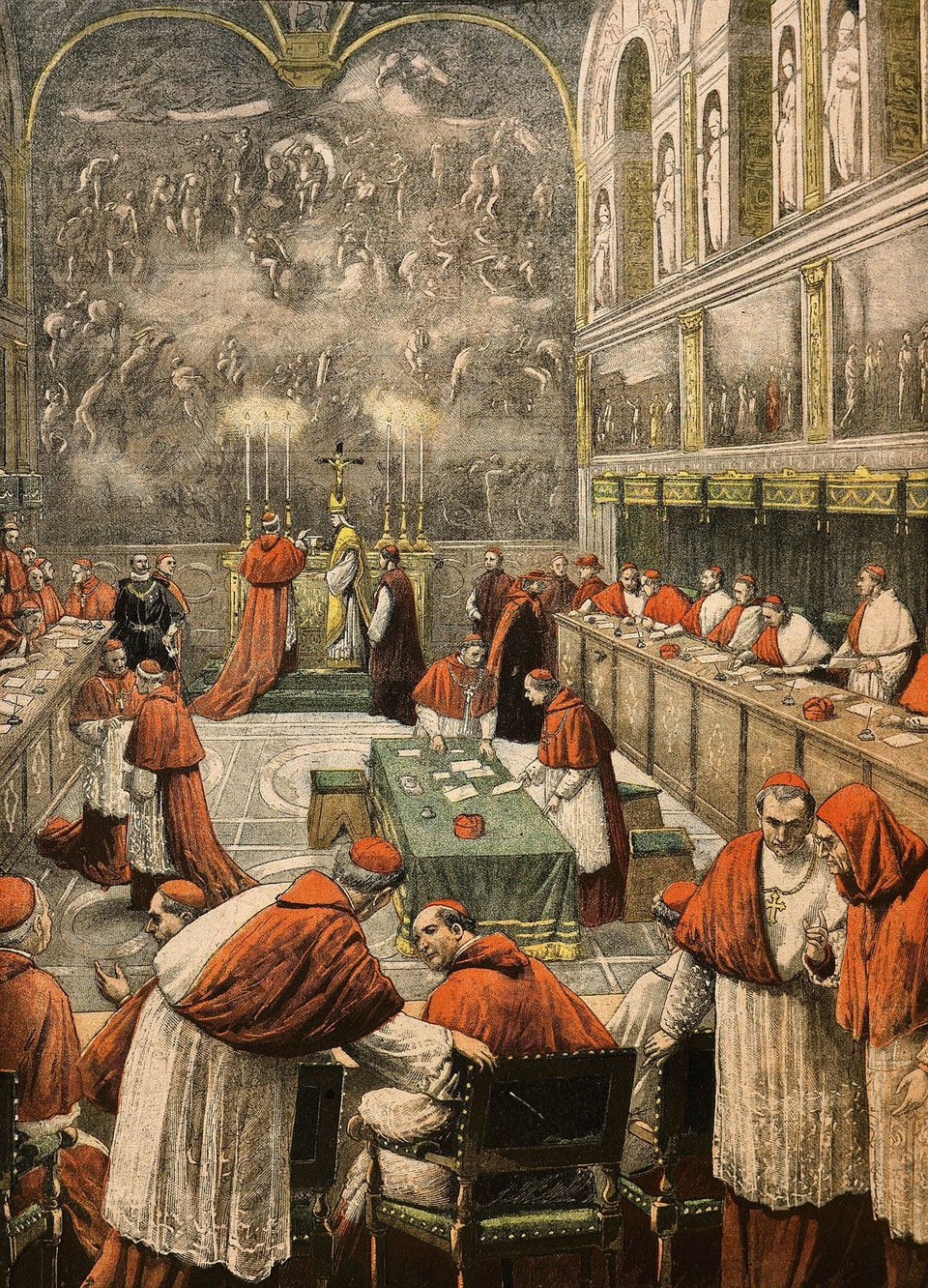

“Julius II, when he gets into power, does so largely by claiming he's going to befriend the leftover Borgia faction,” says Palmer. “They therefore don't resist him at first, and then he destroys them.” There would be a lot of destruction. Notoriously bellicose, Julius spent more of his pontificate on the battlefield than at the Vatican. According to Palmer, “when Michelangelo asked what book His Holiness wanted to be holding in his portrait statue, Julius answered, ‘Give me a sword, I’m no scholar.’” Still, his lasting legacy would be patronage, not conquest: it was Julius who commissioned Raphael to paint The “School of Athens” and Michelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

1513: The Young Pope

On March 9, 1513, the college of cardinals elected 37-year-old Giovanni de Medici as Pope Leo X. “God has given us the papacy,” he wrote to his brother Giuliano. “Now let us enjoy it.” It’s an apocryphal quote, but one that resonates today—and not just because of this week’s conclave. It also misses the context, notes Palmer. “The context is that he was dying when the papal election began. They carried him in on a litter. His intestines had ruptured, and he was lying on the ground, having last rites in the middle of the papal election. He had no hope of living, let alone becoming Pope at such an incredibly young age,” she says. “But Leo comes out the other end as Pope. He lives. So when he says, ‘Since God has given us the Papacy, let's enjoy it’ he's partly joking, but he's also indicating what he's going to do, which is focus his energies on art and culture, not warmongering and politics.”

His brush with death reinforced Leo’s sense of destiny. Raised alongside Michelangelo, he was the first pope elected in the Sistine Chapel since its ceiling had been painted. If he felt like the hand of god was hovering over his election, who could blame him? In many ways, the Vatican under Leo marks the pinnacle of High Renaissance culture, but while he was selling benefices and indulgences and commissioning works of art, discontent was stirring. Today, Leo’s pontificate is best known for underestimating the threat posed by Martin Luther and the nascent Reformation. Are the stakes of this week’s conclave as high?

-

This piece was brilliant and hilarious! I learned way more about Conclaves than I wanted to but worth the full read.

Thanks ,I'm sending it to friends who love to learn these historical details

Add a comment: