Q&A: North America's backyard tropical fruit

It's somewhere between a mango and a banana, and for one writer, its a bit of joy when it comes to food

(Paw Paw by JoLynne Martinez on Flickr)

Coming across a truly joyful climate story is unfortunately rare, but coming across one that has local relevance is even rarer. Which is how I felt when I saw journalist Whitney Bauck’s short feature on the paw paw, a tropical-tasting fruit that grows in eastern North America that’s starting a bit of a comeback. As she writes in the story, pawpaws grow from northern Florida and western New York to eastern Kansas, and “boasts a soft, custardy flesh with a mild flavor somewhere between a mango and a banana.”

But these native fruits aren’t a regular staple in North American homes, in part because they are pretty resistant to the way we get most of our fruits and vegetables: at the grocery store. I wanted to talk to Bauck more about why I’ve had mangos but not paw paws, and the potential climate benefit of the fruit. This interview has been condensed (it was an exciting subject!)

What got you interested in paw paws?

Whitney Bauck: They first stuck out to me when I was walking around in New York City with a friend who works for the New York Restoration Project. She showed me some paw paws trees and said they were going to fruit later this year.

I was super interested in fact that there’s just these fruit trees growing around Manhattan — that’s something I associate with other parts of the world. In California there’s lemon and orange trees; where I grew up from the Philippines you might see a papaya tree growing in an empty lot. It’s one thing if someone has a backyard and they plant things they are lovingly tending. It’s another thing that this is just growing in a park. You could not even know its there and its going to bear fruit that you can eat if you wanted to.

When paw paw season came around this year, it was really interested in tracking some down myself and you know, learning more about this native fruit and why so few people know about it.

Paw paws have a very broad native area and has a history of being eaten as food in North America. Why has eating them become so rare?

Well, a lot of that has to do with the fact that they’re kind of big ag[riculture] proof: they have a really short shelf life. They’re pretty hard to ship or to store. So that means that you just don’t see them in grocery stores. And if you think about it, that’s how most of us encounter food and fruit these days. If we haven’t ever seen it in a grocery store, there’s a good chance that we’re not going to know that it exists or what it is.

There are still people who really love pawpaws and they have kind of a cult following. But the fact that no one has really figured out how to commercialize this fruit is a big part of why it’s not better known and not more popular with Americans even though it grows native here. This is where it’s meant to be.

It feels like it should be a farmers’ market thing?

They do get sold in some of these places, but it’s not like apples or pears where they are at a farmer’s market during every weekend in their season. You have to just kind of catch it when they happen to be ripe and when you people might be selling them.

Something that I remember within my lifetime is suddenly avocados appearing in grocery stores — but that was a big commercial effort. Do you think paw paws need their own marketing campaign or is that something that it wouldn’t even work because of the short shelf life?

I mean, I can buy figs in New York City that are insanely expensive — but they’ll come in a plastic clamshell, where they’re each cradled, [despite fig trees growing in the city]. My current theory is that if there was more demand and or investment in paw paws, that someone could figure out a way to domesticate them. There was a time in American history when there was a question whether blueberries or paw paws were going to become the next big thing. Because at the time they were both these fruits that you could only find in the wild. Figuring out how to commercialize these things is the challenge.

So how can people spot paw paw trees in the wild? What are you looking for?

They have these really big, kind of dark green, glossy leaves that grow in a straight line out from each other. They’re not like a big central trunk, as much as they kind of go up almost like bushes. They can grow really huge: there’s 100 year old plus paw paw tree in the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. And it’s huge, but it’s not like it has a big central trunk. Honestly the best way is to look at pictures.

What kinds of areas do they grow?

So when they’re young, the saplings need a lot of shade. Once they’re older, they prefer more sun. They also prefer to be pretty wet. Often they’ll be near a river or stream, in low lying areas. I heard a few growers who didn’t even make it into my piece saying, you know, they have this land and everything else got flooded and it was a really poor crop that year. But the paw paws were fine because they really liked having a lot of water.

What’s the season for them actually bearing fruit?

This depends a little bit on where in the country you are. I was talking to a grower in Ohio, who heads up the Ohio Paw Paw festival – the biggest in the world – which they do in late September, because that’s sort of the peak of ripeness there. Whereas like here in New York City, I think that into the first or second week of October this year, you know, there were still sort of ripe.

Are these being farmed in addition to being in the wild? How long does it take from putting the seed into the ground to actually get trees that are bearing fruit?

Five to eight years – right now there’s no one growing paw paw commercially at an orchard-like scale. The biggest grower in the country, which is essentially the biggest grower in the world, grows paw paw that’s he’s planted and cultivated on his land. But he actually sources a lot of the paw paws that his operation processes through paying neighbors to forage in the area. There are a lot more farmers who are planting a little parcel of paw paws on part of their land.

I mean, it also sounds like a something to plant in your backyard

Absolutely. And it’s such an incredible sort of investment in the future. It takes a bit for them to start fruiting, but then once they do it can be a source of food for generations of people you’ll never even meet. To some extent that can be true with a lot of different kinds of crops, but it’s a it’s a very beautiful idea to me that you could plant something that your grandchildren could be eating from 100 years from now.

One of the people quoted in the story says they see paw paws as a potential climate solution— it’s a local food that could replace tropical fruits that are being transported long distances, without the emissions that entails. What other sorts of similar local agricultural efforts have you seen pop up?

There’s been sort of a growing re-interest from the public in foraging, and so much of that is about learning to see food where it already exists around you. I wrote a story last year about Alexis Nikole Nelson, who is an Ohio-based forger who makes a lot of foraging content for Tik Tok. She walks down the street in Ohio and it’s like a grocery aisle: she sees food everywhere in a way that I wouldn’t know how to see.

I think a lot about fungi and mushrooms in particular, just because I’m also a mushroom nerd. There are a lot of mushrooms that also resist that commercial agricultural model, but they’re really beautiful foods. And really, the only way to access some of these is to go foraging. Like we haven’t figured out how to grow chicken of the woods at a commercial scale. You’re probably only going to find it if you learn how to spot it and harvest it from the woods yourself. And there’s something that’s kind of beautiful about that and the way that it forces people to reconnect with the natural world. A lot of people are hungry for more of a sense of connection to where their food comes from.

Thinking about eating with the climate in mind can feel really overwhelming to people and and can become about this individual action thing of: Am I doing the right thing? Am I being as sustainable as possible? But what I would like to see more than that, is for people to see that there’s a lot of joy in it.

I think the paw paw story for me has been just this really joyful thing of like finding that there’s just foods like growing out of the concrete here. Food can be all around you, if you learn to engage with it that way.

Thanks to Whitney for talking to me. I’ll be on the hunt for paw paws next year.

(Paid subscribers make this newsletter possible, from the technology costs to the coffee I consume writing it. Become a paid subscriber here. Enjoying this newsletter? Forward it to a friend!)

More Local Climate Stories

Power to the People: Could New Orleans take control of its power utility? | The Latest | Gambit Weekly | nola.com

Going public could come in many forms.

Climate change threatening ‘things Americans value most,’ report says - The Washington Post

The latest National Climate Assessment also finds that the United States has warmed 68 percent faster than the planet as a whole.

Aguirre-Torres details resignation from Ithaca sustainability leadership, fears over Green New Deal - The Ithaca Voice

ITHACA, N.Y.— In his relatively brief time as the City of Ithaca’s Director of Sustainability, Dr. Luis Aguirre-Torres put Ithaca, a city of little more than 30,000, on the international […]

Piquette, a ‘wine tea,’ is becoming popular in California

Piquette, made at the end of the wine harvest, is made from upcycled grape skins.

:focal(0x0:3000x2000)/static.texastribune.org/media/files/20d7a4466e39e116908a592bcc99f7ec/Port%20Arthur%20PYH%20TT%2006.jpg)

Port Arthur pollution fight shows how Texas blocks citizen protests | The Texas Tribune

A local activist went before a judge, arguing for lower pollution limits on two new liquified natural gas facilities. The judge sided with him, but the state environmental agency sided with the companies.

City of Durango to undertake nearly 30 solar, water and power projects all at once – The Durango Herald

Durango City Council approved an energy performance contract this week that will advance work on a package of nearly 30 energy, water and solar efficiency projects at city buildings.

Low-flow wa…

Native-run solar firm aims to lower heating emissions and costs.

Solar thermal panels are a lesser-known sun powered heating option. A northern Minnesota nonprofit is working to install them across tribal lands.

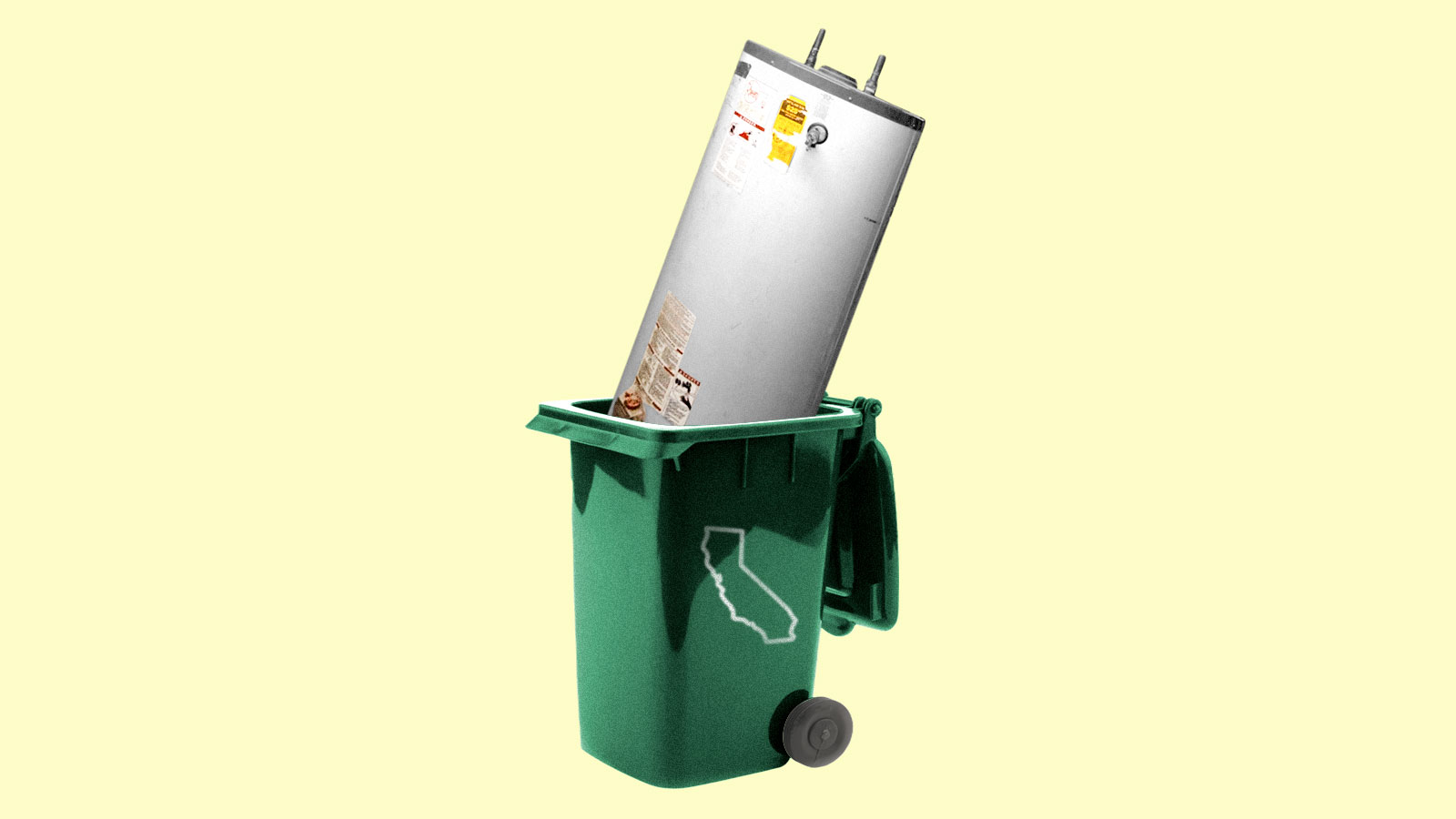

California’s 2030 ban on gas heaters opens a new front in the war on fossil fuels | Grist

The first-of-its-kind plan will purge gas from existing buildings, not just new construction.

Low-income households’ residential solar adoption is rising, but a stark income gap remains the U.S. norm | Utility Dive

More residential solar adoption in middle- and lower-income states like Texas and Florida has helped close the national income gap, according to the report from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

A Very Special Clothing Swap with Avery Trufelman of Articles of Interest Tickets, Wed, Nov 16, 2022 at 6:00 PM | Eventbrite

From Radiotopia & Articles of Interest

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/adn/K22J2AJTQZEWDDFEI6NYIRMUEA.jpg)

Add a comment: