Seeing Past the Trees

There's been Nobel prizes for illuminating how electrons move and quantum dots, as well as 21,000 to 23,000 year-old human footprints. Jon Fosse won the Nobel for his plays and novels. Sure, a new issue of Small Wonders magazine is coming out, but the important news from last month is all about my puppy. Never fear, I have a new picture of Feferi the Corgi puppy at the end of the newsletter. But first, let's talk lidar.

Finding Traces of Humans' Earthworks Thanks to Old Data

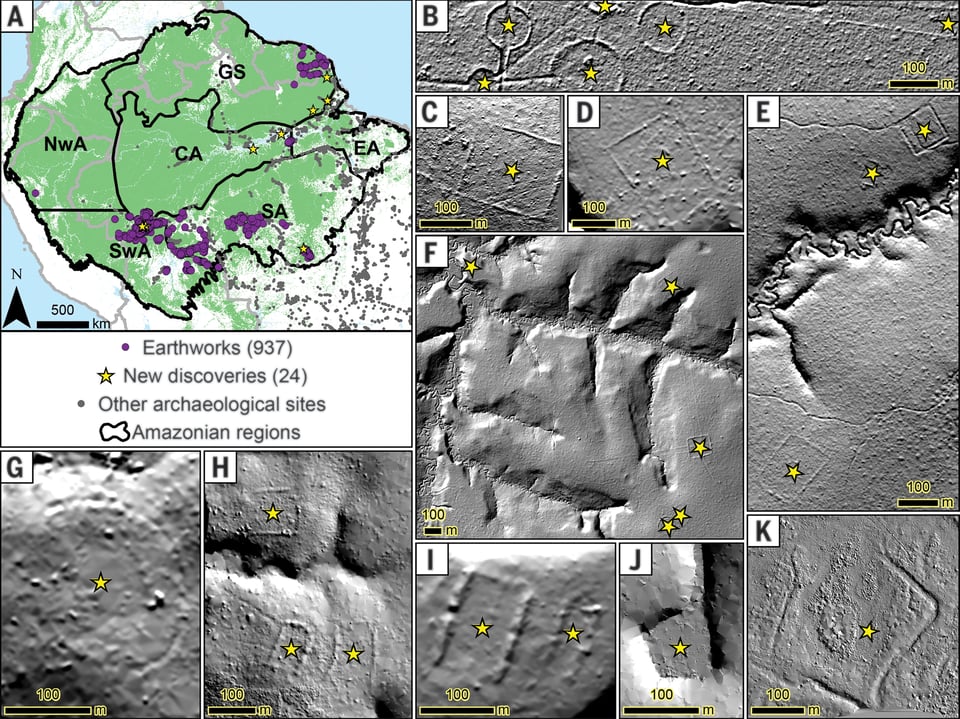

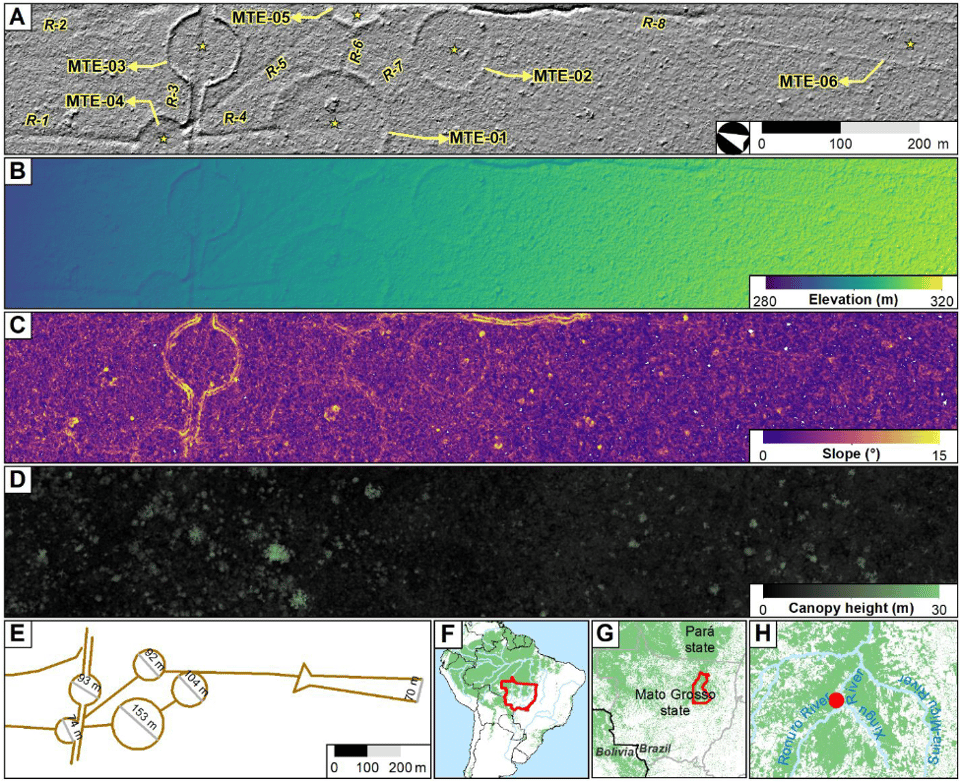

When humans build settlements, they move dirt around, mounding it up into walls and digging out ponds and ditches. As humans have cut back the Amazon rainforest, we've discovered pre-Columbian earthworks through a mix of on-the-ground and high-resolution satellite terrain surveys. Even after a thousand years, with the ruins covered by soil and grass, evidence of the indigenous peoples' settlements remain carved in the earth.

That's just in the part of the Amazon we can easily see from space. What about under its thick forest canopy? Lidar lets you measure distances by sending pulses of laser light and timing how long they take to return. It's incredibly precise: you can measure distances with centimeter accuracy given the right set-up. You can use it to create terrain maps by flying over the Earth while shooting it at the ground. In fact, you can create terrain maps even when trees hide the ground. Once you have a terrain map, you can look for geometric patterns that indicate human earthworks hidden beneath the dirt. Now, researchers found new earthworks hiding in ten previously-collected sets of lidar data. Based on their results, the researchers estimate that tens of thousands more earthworks may hide across the Amazon.

This is deeply cool. It adds to previous evidence of human habitations in the Amazon, which in turn can impact indigenous peoples' efforts to assert land rights. It may help slow land grabs and deforestation. All of that is very important, and also subjects I can't speak authoritatively to. What I can do is explain how you can see through forest canopies with lidar.

The secret is that lidar can't actually see through leaves. Instead, it sees through holes in the canopy. When you bathe a tree in laser light, a small amount of the light reaches the ground and scatters back up. Some of that scattered light sneaks back through the leaves and to the lidar to be measured. It's hard to see the ground, though, because the laser light doesn't have much of a chance to reach the ground and then come back to you, and even if it does, it'll be overwhelmed by the light bouncing off of the leaves.

To get around that, you need two things. One, you need to shoot a lot of laser light at the ground, over and over and over again, to boost the chance that the light gets past the canopy. Two, you need a detector operating in geiger mode. Lidars use detectors that turn incoming photons into electric current. Normal lidar detectors operate in a linear mode, where doubling the number of photons that reach the detector doubles the current. Below a threshold number of photons, though, the detector won't register any light because of its noise. It's like trying to hear a song in a restaurant over the sizzle of the grill. Geiger mode detectors, however, create so much current when any number of photons reach them that they can detect single photons.

The researchers still had to do a lot of data processing to find the earthworks in the lidar data. They had to find the points that corresponded to the ground, throw out noisy points, and then stitch them together into a digital elevation model. But when they were done, they had images that humans could look at to identify potential earthworks.

What's even wilder to me is that the researchers didn't collect any data themselves. They used three separate datasets, one of them with seven data collections going back to 2008, to find earthworks that had previously been overlooked. I'm a big proponent of keeping data available for other researchers to evaluate. Researchers solved the Pioneer Anomaly, in which the Pioneer space probes appeared to be slowing down more than they should have been, by combing through old data, some of it literally pulled out of dumpsters right before it was hauled away.

In short, a new sensor combined with sophisticated methods of data analysis let researchers re-evaluate data and further demonstrate indigenous peoples' claims to land, pushing back against the narrative of the Amazon as an unspoiled forest untouched by people. It's a great example of how science can impact not only our understanding of the world but also the narratives we tell about it.

What's Up With Stephen?

Oh, hey, the magazine Podcastle reprinted my story "The Sigilist's Notes on the Fell Lord's Staff," this time with narration by yours truly. It's your chance to hear me be an arcanist pining for his evil lord. If you'd like to hear me talk in person, I'll be at Multiverse Convention in Atlanta on October 20-22.

What I'm Vibing With

- It's Fat Bear Week!

- Yes, I know, I should ignore annoying Tweets, but it's hard when someone is wrong on the internet.

- It makes me sad to see old sites becoming less useful, often ahead of a possible sale. Discogs, the 22-year-old site for vinyl and CD info and sales, is the latest example.

- This profile of Dr. Katalin Karikó, who just won the Nobel prize for her work on mRNA vaccines, is superb.

- Let's hear it for the Writers Guild of America!

- Dan Olson did an unsurprisingly-great deep dive on the GameStop meme stock craze and, more critically, what came next for the r/wallstreetbets community.

Finally, as promised, a picture of Feferi, who's taken to sleeping on us.

Add a comment: