Entangling Quantum-ly

Entangling Quantum-ly

It's been quite the month, what with a cold winding its way through our household and a slightly-less-new, slightly-less-puppy-ish Corgi refusing to take our illness into account, but we're still trucking, and then my friend Alex White1 asked me about quantum entanglement and how writers use it for faster-than-light communication, so this newsletter is entirely their fault.

My explanation is long enough that I'm breaking it into two parts2. This first newsletter covers what quantum entanglement is and why people want to use it for FTL communication. Next week's will break down why that breaks down. If you're an SF writer and just want the teal deer, quantum entanglement won't let you communicate faster than light, but go ahead and pretend it does if it makes your story go3.

Also, since explaining quantum mechanics can get boring, and because stock illustrations of quantum entanglement are buck wild, I'll intersperse my favorites throughout to entertain both of us.

What Even Is Quantum Entanglement?

Take two particles. Prepare them in a special way. Measure an attribute of one particle, like its momentum, or polarization, or spin4. Then you know what the other particle's attribute is, even before you measure it. That's quantum entanglement. Simple!

Okay, maybe that's too simple of an explanation. Let's start with what "measuring an attribute" means. In quantum mechanics, a particle's aspects like position, momentum, or spin are encoded in its quantum state. Wave functions are how we describe quantum states using math. "Making a measurement" is interacting with the particle to determine the information captured in its quantum state.

We're used to the classical world, where objects have consistent states. The coffee cup next to me is in a single location. It's not moving. I'm certain about both of those things. But when it comes to a quantum system, that certainty vanishes. A particle can be in superpositions of states, where its wave function is two or more pure states added together. Imagine an electron that can have a spin value of either spin up or spin down5. It can also be in a state where it's a little bit spin up and a little bit spin down. When we measure its spin, it'll be either up or down, with a probability described by its wave function, but until then, it's neither up nor down. Its spin is uncertain.

In special circumstances, you can arrange for two or more particles to have wave functions that are correlated. The wave function of one is related to another. Take two electrons that can have spin up or spin down, and entangle them so that, combined, they have a spin of 0. That can only happen if one electron's spin is up and the other's is down so that they cancel out. We don't know which electron has a spin that's up or down. But if we measure the first electron and find that its spin is up, then we know the other one's is down without measuring it.

Now for the buck wild part. Entangle two particles. Carefully separate them so they're not next to each other. Measure one's spin. If it's up, the other one's will be down, even if they're separated by, oh, say, 1,200 kilometers.

Oh, yeah, and that appears to happen instantaneously.

That was a lot. Let's take a break and enjoy another stock illustration of quantum entanglement. Oh, and if you've made it this far and aren't a subscriber, consider subscribing! It's as free as a free electron!

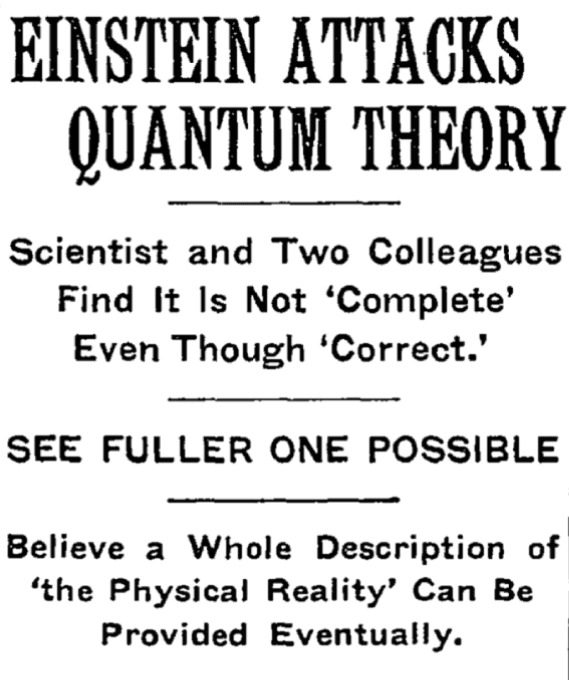

You can measure one particle and the other particle's measurement matches? Instantaneously? Faster-than-light instantaneously? That can't be right, can it? Like, doesn't that violate general relativity? Famously, Einstein, along with Podolsky and Rosen6, published a 1935 paper explaining how entanglement was possible under quantum mechanics and therefore the theory had to be broken. As proof that click-bait science headlines long-predate the internet, the New York Times ran an amazing article that Einstein hated.

Anyway, Einstein also wasn't happy with the idea of entanglement, famously calling it "spooky action at a distance." But a series of experiments groundbreaking enough to earn a Nobel prize showed that quantum entanglement is real. Quantum mechanics isn't broken. Entanglement describes an actual phenomenon.

If quantum entanglement means measuring a particle in one location immediately determines what will be measured for a second particle in another location, no matter how far separated, then we've done it! Faster than light communication, everyone!

Alas, no. I'll break down why that is in next week's newsletter, along with the clever schemes people have come up with to try to make FTL comms happen, to no avail. But even if science has ruined our plans, why quantum entanglement doesn't mean FTL communiction is still really interesting. And in the end, it's okay if you want to (mis-)use it in a science fiction story.

Okay, one more amazing stock photo.

What's Up With Stephen?

As mentioned, it's been a month of illness in my house. But there's good news! After having not much happen writing-wise in 2023, I've got two short stories coming out very soon, one about a train spirit and leaving the small town you grew up in, the other about uploaded humans figuring out gender. I can't wait to show you them.

Also, and this is wild to me, we're more than halfway through the first year of publishing Small Wonders magazine. Issue 7 is coming out on the website right now.

What I'm Vibing With

- This person made a Nintendo Playstation with a soldering iron and angle grinder and I cannot believe the build didn't involve people dying.

- Hi, Barbie!

- In the '90s, I spent a semester at a UK theatre school that didn't cost much and had students from all over England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. One student had a very RP accent and got gently ribbed about it. That school shut down in the 2000s. Anyway, here's Peter Capaldi talking about the dearth of support for working-class actors in the UK.

- Loving the books no one else knows about.

- Tom Scocca writes about his medical mystery keenly and with harrowing insight.

- The Washington Post published a survey of American reading habits.

- I saw a lot of bonkers takes about that Post survey, but thankfully Lincoln Michel's was as excellent as you'd expect.

- Lookit this very good Capybara meeting some tiny cousins.

Finally, I know y'all want more Feferi updates, so here she is meeting snow for the first time.

-

Whose books are awesome and you should buy them. ↩

-

Unless it's 2004 and you're writing mundane science fiction, in which case, god bless and good luck. ↩

-

Particles have angular momentum built in. Since spinning objects have angular momentum, we call a particle's intrinsic angular momentum "spin". The particles aren't actually rotating, even though they act like they are. Like, for an electron to rotate fast enough to have the right amount of angular momentum, it would be rotating faster than the speed of light. So, you know, it's not doing that. Think of spin like mass: a number that describes how particles behave. ↩

-

Remember how spin is angular momentum? You can describe it as a vector, an arrow that points along the axis that the particle would be spinning around, if it were actually spinning like a top. "Spin up" and "spin down" mean that the vector can point in one of two directions. ↩

-

Why, yes, these are the same Einstein and Rosen whose general relativity papers suggested wormholes, and are the source of so-called "ER bridges" (sometimes "EPR bridges") that show up in fiction and more speculative papers on the arXiv. ↩

Add a comment: