Just in time for a massive transformation in the way we use and consume media in the United States, I’ll be sending you a lot of letters. They’re based on an introductory media studies course I taught in the spring of 2024 at the University of San Francisco.

I owe a lot to my USF colleagues and students, who taught me how to teach media in the twenty-first century. My students asked unexpected questions and spurred me to rethink my approach and the topics I covered. They also introduced me to pop culture and perspectives I never would have discovered on my own, outside the classroom. With these letters, I hope to extend that classroom experience to you, my reader.

Each letter will be loosely based on a lecture from my course. I’ll also include some in-class exercises we did, to suggest ways you might explore media analysis on your own. In today’s letter, I’ll introduce you to the big themes of this series, and give you a fun introductory exercise.

Media studies gives us insights into what media is, and where it comes from. But most importantly, it teaches us how to challenge and change the messages that our media carries.

The Communications Crisis

Let’s start with what’s happening right now. We are neck-deep in a communications crisis in the United States. From century-old newspapers and magazines, to brand-new social media platforms, our information sources are trying to reach audiences who no longer trust them. Their owners — often conglomerates and oligarchs — are trying to make money by controlling “content products” that don’t behave like any other kind of commodity.

The media landscape is shifting under our feet, and sometimes it’s impossible to know what’s real.

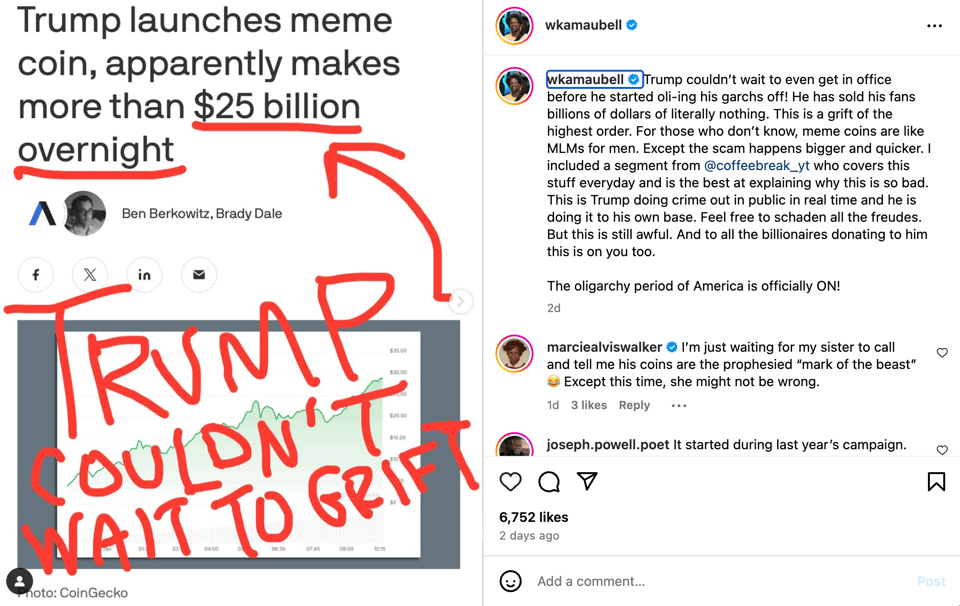

The signs of our communications crisis take many forms. They include things like Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos’ decision to prevent his newspaper from endorsing a presidential candidate in 2024; but they also include the ubiquity of AI slop and conspiracy theories about the California fires, as well as the maelstrom of confusion around the Congressional TikTok ban. If you’ve been upset or confused by any of these events, that’s not because you’re “too online” or are “taking it too seriously.” It’s because what happens to our media affects us personally as well as politically.

Studying media is, in a sense, the study of our everyday lives. The stories we share, create, and consume shape our identities. The good news is that we also shape our media, and we can reshape it.

Media is Everywhere

Where do we find media? Obviously it’s in our phones, televisions, and theaters. Less obviously, we encounter media in street signs and advertisements, public statues and graffiti. Wherever people live, media messages are everywhere — they are written on walls, posted in windows, blasted from speakers, and pinned to people’s lapels. Even if you hike into the deep bush, you still carry it with you in the form of maps and tags on your gear. Media is ubiquitous.

Because you live in a mediascape, you’re already an expert in some kind of media. Whether it’s music, games, a streaming series, sports, news, or books, there’s some kind of media you could probably lecture me about for hours — or days. That means you already understand how some media works. If you like classic romance stories, for example, you know the characters always fall in love at the end. If you like American football, you know there are always over-the-top ads during the Superbowl. If you listen to pop songs, you know they always have a hook. To a large extent, you know what to expect from the media you enjoy.

But there’s another side to this expertise. Consciously or unconsciously, you’re internalizing a ton of messages from the media you consume. You’re picking up ideas about small things, like where to buy the best clothes and how to talk to strangers. You’re also inundated with messages about more fundamental issues, like what kinds of jobs are good, how to educate children, and whom you should date.

We aren’t always aware of all the ways our media affects us. And yet we depend on it to tell us who we are, and how to navigate the world.

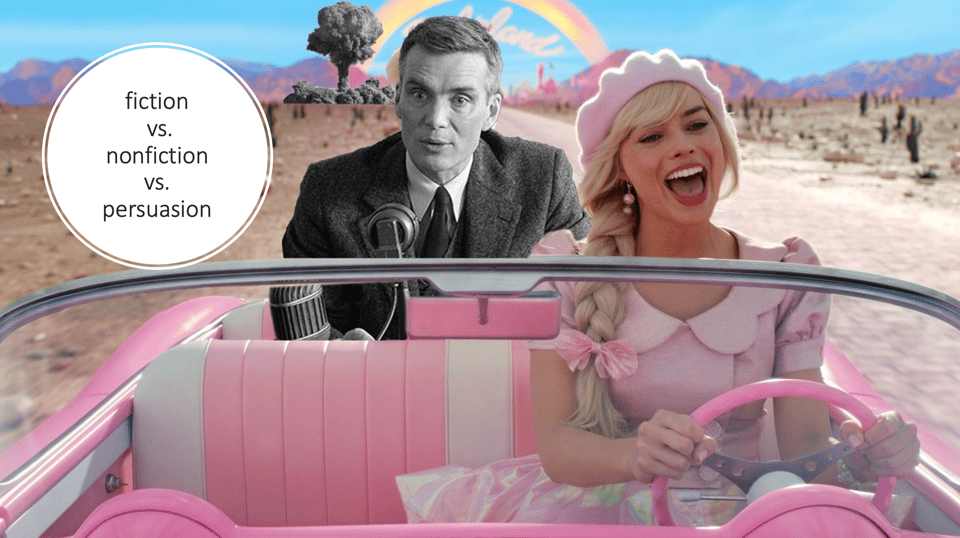

That’s because media is one way we create a public sphere, an arena of shared stories that includes fiction (made-up stories), nonfiction (stories based on facts and evidence), and persuasion (stories intended to change our behavior).

Why do we spend so much time swapping stories in public? One basic reason is that we do it for pleasure, to entertain each other and escape from boredom. But we also do it to share important facts about safety, to consolidate a sense of shared purpose and identity, and to mobilize people to do something. We’ll talk more about all of these in later letters.

The public sphere is often messy, with one kind of story standing in for another. We can use seemingly frivolous stories about celebrities to spark conversations about deeper social issues. Consider the wave of stories last year about how pop star Taylor Swift might be a psyop deployed by the Biden Administration. This sounds weird until you think about how powerful and influential Swift is in the public sphere. She’s become a de facto political force. Plus, she has spoken out about a few political issues – she’s against Trump, and she’s pro-abortion and pro-LGBT. As a result, she’s become a icon we can use to debate topics in the public sphere that have nothing to do with the Eras Tour.

This is just one of many examples of how complicated and multi-layered the messages can get in our mediascape.

Culture + Tech = Media

The study of media is always also the study of technology. Indeed, you might say that culture plus technology equals media. Famously, the printing press was the first technology that transformed media access, allowing thousands of people to read the same book at the same time.

During the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, people have developed countless new media technologies, from radio to AI. That’s why we’ll be focusing largely on these centuries as we look at what media is.

Once you start thinking about your media as a function of technology, you’ll discover that tech has always influenced the content that’s available. A book can’t do what a movie does, and vice versa. Tech also changes the way media is disseminated. Movie theaters made it possible for millions of people to watch the same stories at the same time. Broadcast TV and streaming video allowed millions of people to bring theaters into their living rooms. And social media allowed us to share our living rooms with the world.

Importantly, state regulations and corporate rules affect media tech as well. Laws shape what we can communicate using media. Companies control the technology that allows us to share media.

We cannot ever analyze media without also thinking about the tech that makes it possible.

Welcome to Media Studies

I’ll end this letter by giving you a glimpse of what’s to come in this series.

We’ll start by exploring various methods of media analysis, or methodologies, which include ideas borrowed from philosophy, legal studies, and critical theory. Then we’ll turn to media history. Get ready for some deep dives into radio and pulp fiction, as well as classic movies and TV, early twenty-first century memes, social media, and large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT.

Finally, we’ll conclude with a series of letters devoted to the question we must always ask when looking at a piece of media: What is real? This is when we’ll talk about persuasion, propaganda, and how to tell the difference between fiction and non-fiction (hint: it’s much messier than you think).

I hope you’ll join me on all or part of this journey, deep into the heart of the mediascape. Remember, the public sphere belongs to us, the public. We may not control the media in it, but we can control how it affects us.

In my next letter, I’ll introduce you to a brilliant researcher whose breakthrough discoveries in the 1970s utterly transformed the way people understand media.

Let’s Do a Media Exercise!

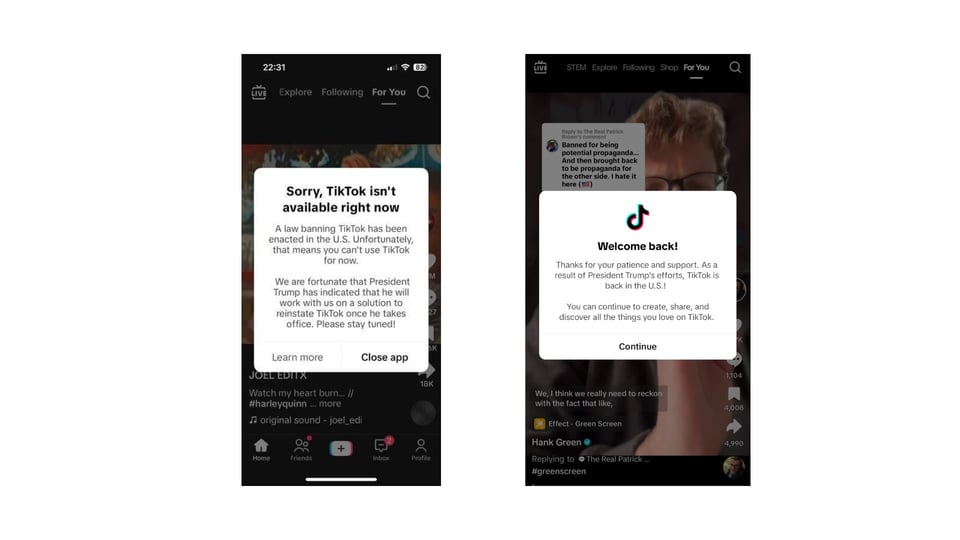

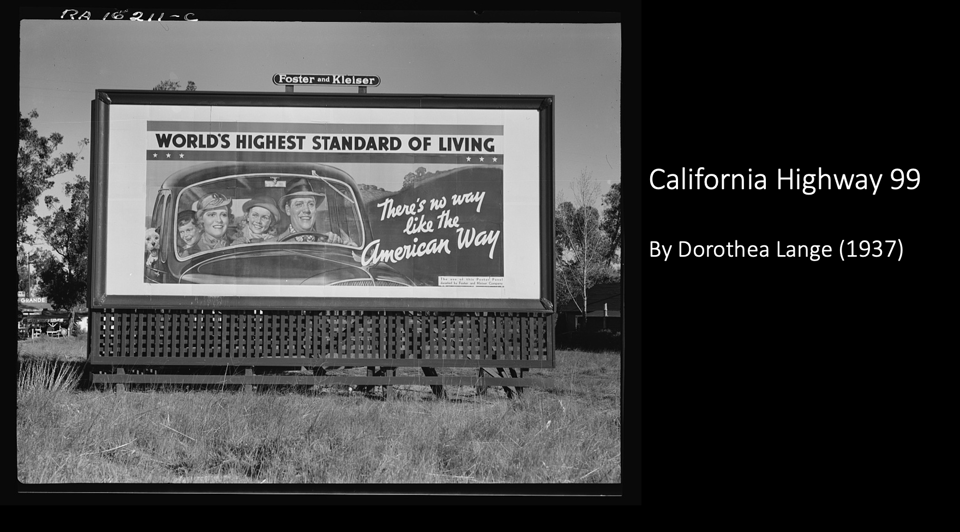

Sit down with some friends, or just relax by yourself, and look at the following pieces of media. Try answering the three questions below about each one. (There’s a key at the bottom if you’re desperate to know the answer to the first two questions — the third you have to figure out for yourself.)

- Can you identify who or what this is?

- What kind of technology created this piece of media? (I realize these are all digital images and video, but what kind of tech created the original piece of media here?)

- What messages are being communicated?

Figure 6

Key:

Figure 1: This is a billboard advertisement for cars, and it’s a photograph taken by Dorothea Lange.

Figure 2: This is a recent post on Instagram by media critic W. Kamau Bell. The post depicts a news story from online outlet Axios.

Figure 3: This is an advertisement for McDonalds, featuring K-pop superstars BTS.

Figure 4: These are two editions of The San Francisco Chronicle, a print newspaper.

Figure 5: This is a really hard one! It’s a screenshot from Streets of Rage, a 1991 Japanese videogame for the Sega Genesis. But it’s actually a meme from the 2010s. The phrase “only trust your fists police will never help you” was added later. It’s a reference to the way players could call a cop car, but only rarely, so maybe it’s better to use your fists. Clearly it has other meanings, too. 😀

Figure 6: This is a clip from the opening scene to the 1985 movie Brazil. You decide what kinds of media technology it’s representing, and what messages it’s trying to parody.

You just read issue #35 of The Hypothesis. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.