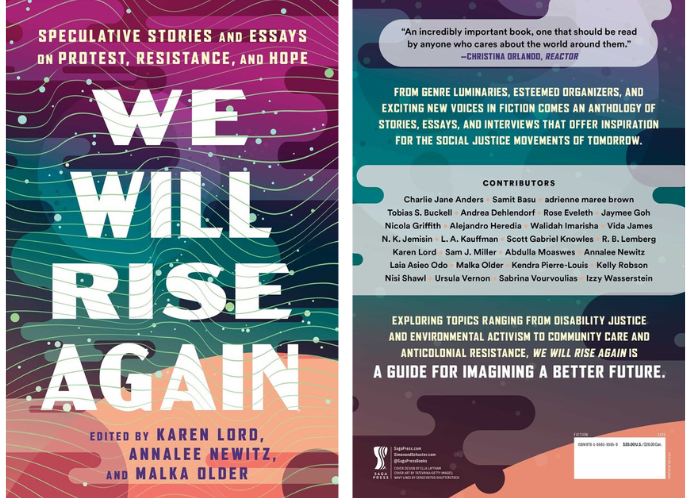

Before I tell you a wild story about a man I cannot forget, I have book news! We Will Rise Again: Speculative Stories and Essays on Protest, Resistance, and Hope, the anthology I co-edited with Karen Lord and Malka Older, will be out on December 2! Come to Booksmith in San Francisco that night to celebrate with five amazing authors and activists who are in the book. You can also read one of the stories on Electric Lit, and pre-order it from your local indie bookstore today!

In other bookish news, I have been surprised and delighted by the response to Automatic Noodle – it debuted on the USA Today and Indie bestseller lists, and has already gone into a fifth (!!) printing. You can order autographed and personalized copies of all my books from Noe Valley Books and Green Apple. Bonus: You can buy Automatic Noodle swag (designed by Lucy Bellwood) from a website (designed by Mike Monteiro) that is a facsimile of the old-fashioned HTML website the robots create in the book.

Remember: books are great holiday gifts!

A Man I Will Never Forget

Thanksgiving season always makes me think of fascism, but that’s especially true this year. One of the many things I’ve been doing to cope with my political dysphoria is to revisit classic works of anti-fascism from the mid-twentieth century. When Trump was elected in 2016, I did a deep dive on the largely forgotten sociological study The Authoritarian Personality. It’s wild how much that book has influenced our understanding of why people become fascists. But you know what they say: things can always get wilder.

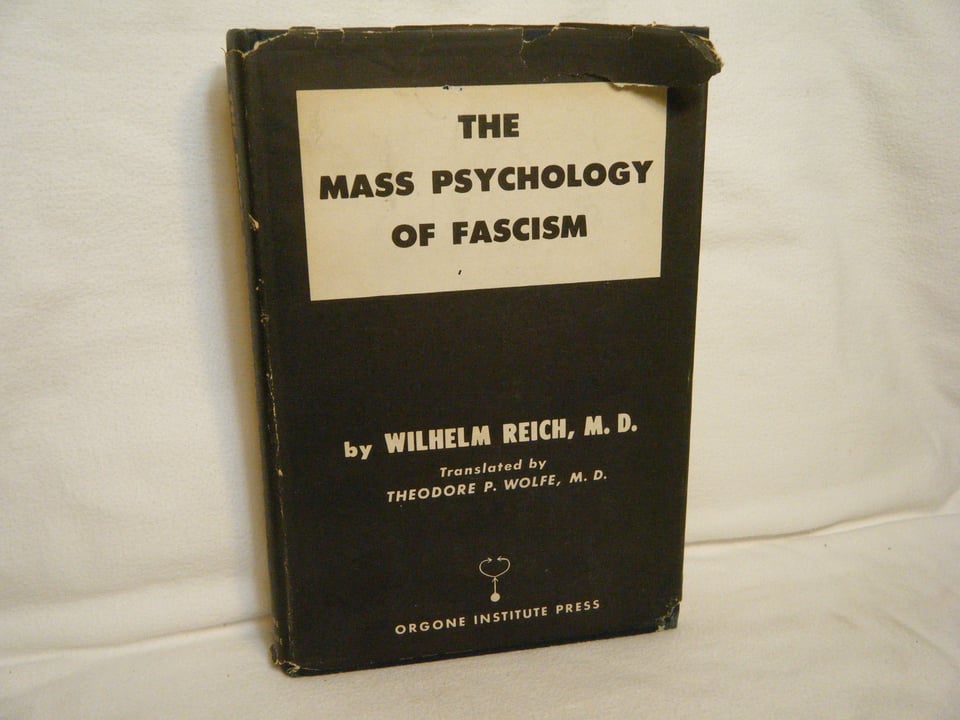

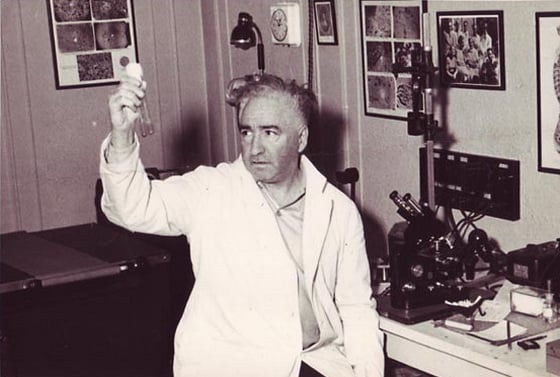

Recently, I’ve been re-reading Wilhelm Reich’s 1933 bestselling book The Mass Psychology of Fascism, written shortly before the infamous psychologist fled Nazi Germany. A keen observer of politics, Reich watched as many of his patients were radicalized by fascist propaganda. He writes about being dumbfounded when liberal women who voted for abortion rights in Germany also voted for Hitler. And he watched in dismay as his leftist friends tried to fight fascism’s “irrational” and “mechanistic-mystical conception of life” with complicated policy recommendations and warmed-over socialist slogans from the 19th century. Why couldn’t smart, rational people combat the liars and hypocrites who ran the Nazi party?

In The Mass Psychology of Fascism, Reich argued that this was the wrong question. Fascism wasn’t a German political problem to be solved with a new progressive platform; instead, it was a problem fundamental to all human psychology. Industrial civilization allowed it to erupt into a mass movement, but fascism was rooted in the contradictions of the modern psyche. Subjected to strict and sometimes violent patriarchy in the home, and shamed into “moral” behavior by religion, people had become anxious bundles of barely-repressed rage and lust. Members of the “civilized” public might say they wanted liberal democracy, but deep inside they wanted to kill, rape, and rule by force. And it was this contradiction that fascism exploited, by offering up Jews and other minorities as targets for their repressed feelings.

As he pondered this idea, Reich became convinced that the nitro fuel in Nazism’s engine was actually sexual repression. This could explain why Hitler and his cronies were obsessed with destroying the nascent LGBT rights movement in Germany, suppressing all mention of sex in schools, and forcing women to become nothing more than “child-bearers.” If the state could suppress all forms of sexual expression other than reproduction in a monogamous marriage, then it could build an army of people whose unconscious minds were basically houses made of dynamite. Or so Reich’s logic went. Even the “race theory” at the heart of Nazism fit into Reich’s model, because Hitler worried about Jews diluting the pure blood of Aryans – through sexual relations, of course.

And Reich wasn’t completely wrong. I’ve been struck by how many of his observations about sexual repression map neatly onto today’s MAGA movement. Speaker of the House Mike Johnson is proud to reveal that he has an anti-masturbation app on his phone; libraries and schools are banning books about LGBT characters; and Trump loves to demonize immigrants by calling them rapists. Reich would have no trouble recognizing the fascistic implications incel culture and the manosphere’s obsession with purity.

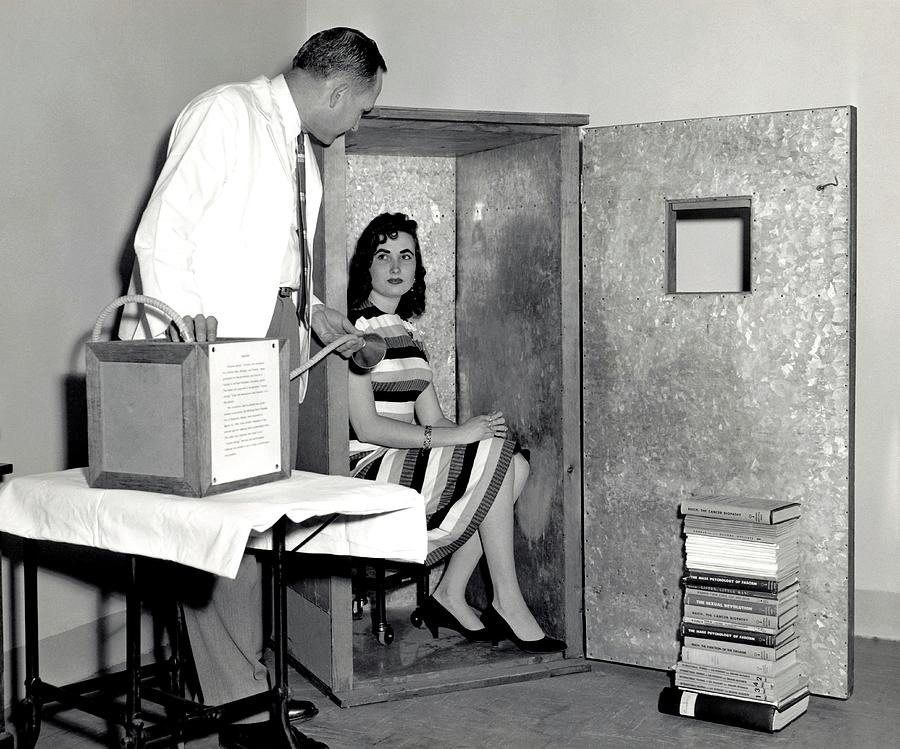

Reich would also, unfortunately, find common cause with Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Dr. Oz. In the late 1930s, he claimed to have discovered the key to fighting fascism. It was the orgone, a unit of erotic life energy that most people had lost. But luckily, if you paid Dr. Reich for one of his “orgone accumulators,” you could be cured. Orgone accumulators were wooden boxes lined with a thin layer of metal, and looked kind of like a fancy cabinet with enough room for the patient to sit on a chair inside.

After settling in the United States in the 1940s, he also grew more focused on something he had long advocated: liberating the sexuality of children. Previously, in Europe, he had organized a “Sex-Pol” group that taught “sexual revolution,” an amalgamation of Marxist and Freudian ideas that he believed would result in freedom for people of all ages. His work alienated both Marxists and Freudians. He was kicked out of several psychoanalytic organizations when he began advocating that analysts give their patients deep, painful massages – sometimes while naked.

Reich bought some land in rural Maine which he dubbed Orgonon. There, he taught classes on how to have orgasms that produced orgone energy, and promoted the idea that cancer could be cured by exposure to orgones. He also helped set up a school for youth, where many students say they were physically and sexually abused. According to Reich’s biographer Christopher Turner, Reich knew about the sexual abuse and continued to support the teachers involved. Though Reich himself was never accused of rape, his daughter told Turner that she refused to be alone with her father because “he was really a sex abuser.” After years of negative publicity about Orgonon, the FDA investigated his work and sued him for fraud. But Reich refused to stop selling his orgone accumulators, despite a court order. He was arrested in 1956, and died in prison the following year.

I often think about Reich’s grifter-abuser turn. He wanted to liberate people from fascism, to show them a world beyond the “mechano-mystical” bullshit of authoritarian propaganda. And instead, he wound up replicating it.

Despite his descent into dangerous pseudoscience, Reich is remembered with far more romantic intensity than most of his contemporary critics of fascism. Patti Smith’s song “Birdland” is about Reich, as is avant garde filmmaker Dušan Makavejev’s celebrated film WR: The Mysteries of the Organism. Woody Allen invoked him with the “orgasmatron” in his early comedy Sleeper. Even today, there are echoes of his particular brand of sexual pseudoscience in many new age practices, and his work on fascism is taught in graduate courses on critical theory (which is how I was first exposed to his work).

Reich isn’t taken seriously as a scientist, but he has become a cultural icon. Maybe Reich’s story haunts us because, in the end, he perfectly exhibited all the symptoms of the social disease he claimed to cure. He was not a doctor. He was a patient, whose foundational trauma was fascism itself. And like so many victims of abuse, he passed it on to the next generation by creating a new kind of mysticism that justified sexual cruelty to children and people with mental illness.

Authoritarianism is a powerful form of intergenerational trauma. We forget Wilhelm Reich at our peril, because he stands as a warning of who we might become.

Other things I’ve written lately

I am really excited to be writing regularly for Flaming Hydra, and I have two new pieces up. One is on the history of review bombing, and how it became a form of psychological warfare. The other is a critical analysis the original Wicker Man movie, in dialogue with the incredible author Tal Lavin. Tal wrote about the film’s aesthetics, and I tackled its politics.

My latest columns for New Scientist are about why digital ID cards proposed by the UK government are a very, very bad idea, and how the future of higher education is already being built, outside traditional universities.

Also, I’m psyched about the latest episodes of Our Opinions Are Correct, about the future of science fiction conventions and Frankenstein’s legacy. Our next episode will be our last. Charlie Jane Anders and I have been co-hosting this pod for seven years, and we need to take a break in order to dream up a new project together. We promise to keep you in the loop! I’ll write more about the podcast in my next newsletter.

You just read issue #41 of The Hypothesis. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.