How do you analyze something that is imaginary, symbolic, and exerts its power only in our minds? This, in a nutshell, is the question at the core of media studies. There are no scientific instruments, no mass spectrometers nor telescopes, that help us measure what happens when a narrative enters someone’s consciousness and infects them with new ideas. We have to figure it out using only the meat in our skulls.

And this leads to another question. How do you analyze something that you are emotionally invested in, while it’s running? Studying media is difficult because often it means taking apart the stories that we love, or that have shaped our sense of self. It’s hard to subject our pleasures to self-aware scrutiny.

But that is precisely what we must do. Allowing a story to define you without analyzing it — well, it’s like eating a delicious candy that a stranger gave you on the street. Sure, it could be fine. Delightful, even. Or it could be really, really toxic. Don’t you want to know before you stick it in your mouth?

In my last newsletter, I introduced you to the field of media studies. Today you’re reading the second in my series of letters about how to analyze the media during a communications crisis. We’re going to dive into the history of modern media studies, and talk about one of the founders of the field.

Stuart Hall’s work transformed our understanding of media because he did something revolutionary: he focused on the power of audiences, rather than creators.

Born in Jamaica in the 1930s, Hall described himself as growing up in the final years of colonialism. His father was the first Black man to run the accounting department for United Fruit in Jamaica, and his mother pushed her children to achieve respectability by playing by the colonizers’ rules. Hall had darker skin than the rest of his family, and he recalled in his autobiography that his sister used to jokingly call him a “coolie.”

Never comfortable with his family’s bourgeois aspirations, Hall felt like an outsider from a young age. He eventually left Jamaica when he earned a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford at the age of 19. Upon arriving in England, he found himself an outsider of a different kind. He wrote that he was surrounded by people who simply couldn’t see how colonial history was still shaping their preconceptions — not just about what a young Black man was capable of, but also about how the world should be run. He found himself constantly experiencing what he called “disidentification,” as he attempted to unshackle his identity from other people’s expectations about who he was.

And it was this experience that led to his great insight about how audiences interact with the media they consume.

Message Received

Let’s backtrack for a minute, to provide some context for what Hall did next. In the 1950s, when Hall was at university, media studies was a fairly limited enterprise. Until that point, there had been critics who studied film, mass communications researchers who interviewed media consumers about their beliefs, and theorists including Roland Barthes and Walter Benjamin who analyzed people’s psycho-social relationships with narrative. All of these efforts helped shape a modern approach to storytelling and psychology in an age of industrial media production.

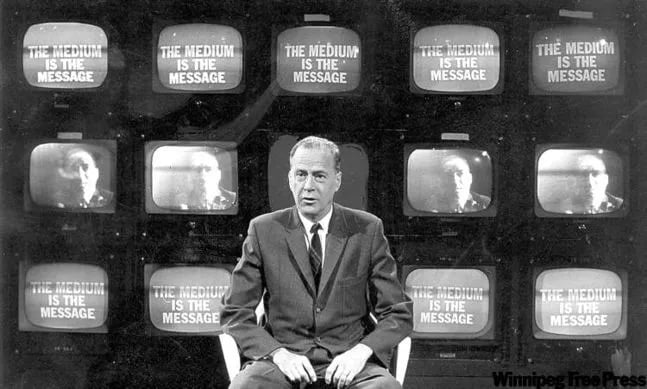

Meanwhile, outside the Ivory Tower, critics and journalists popularized the idea that media had become so ubiquitous that it influenced nearly every decision people made — whether we realized it or not. Among the more famous media analysts of the 1950s and 60s were Vance Packard, whose book The Hidden Persuaders was an exposé about manipulative corporate marketing, and Marshall McLuhan, best known for coining the phrase “the medium is the message.” McLuhan was interested in how different technologies shaped the media, and argued that television had a distinctly different effect on audiences than film and radio.

Most media analysts of the mid-century assumed that communications followed a simple model: sender → message → receiver. The sender was whoever created the media and the receiver was an audience, while the message was a sort of neutral item that passed easily between them. Pretty much all analysis of media focused on the sender, and how they could affect, control or manipulate the receiver. That was certainly what Packard was interested in. McLuhan was investigating the message, asserting that the “medium” (TV, movies, etc.) was in some ways more important than the content.

Few critics had considered the roles of receivers, other than to ponder their inability to resist manipulation and information overload.

That’s when Stuart Hall entered the conversation. In 1973, he published a groundbreaking essay called “Encoding/Decoding in Television Discourse.”

Encoding/Decoding

Before we dive into the insights at the core of this essay, we need one more record-scratch “how did we get here” moment. Hall uses the word “discourse” in the title of the essay, which is a term of art in media studies. Discourse is a collection of ideas in the public sphere that tells us who we are, what to believe, and how to act. (This is a simplification, but it works for our purposes here.) There are all kinds of discourses, large and small. MAGA is a discourse, for instance, as is skincare TikTok. Most of us are immersed in many different, occasionally contradictory discourses.

For Hall, the most important way to understand discourse was through the lens of power. He was inspired by the early twentieth century critic Antonio Gramsci, who used the word “hegemony” to describe how some discourses come to dominate other ones. Hegemony is essentially a collection of discourses that are used by people in power to keep everyone else in line. These discourses could be about religion, the state, sexuality, or any number of other things.

Hegemony always masquerades as common sense, the “norm,” the epitome of moral goodness and sanity. Gramsci wrote his key essays about hegemony from an Italian jail where Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party had imprisoned him for being a dissident. So let’s just say he knew a little bit about how hegemony exercised its power.

Despite his grim situation, Gramsci also speculated about a “counter-hegemony,” full of messages coming from dissidents like himself, pushing back against hegemony and transforming it.

Now, at last, we can talk about Stuart Hall’s ideas about encoding and decoding.

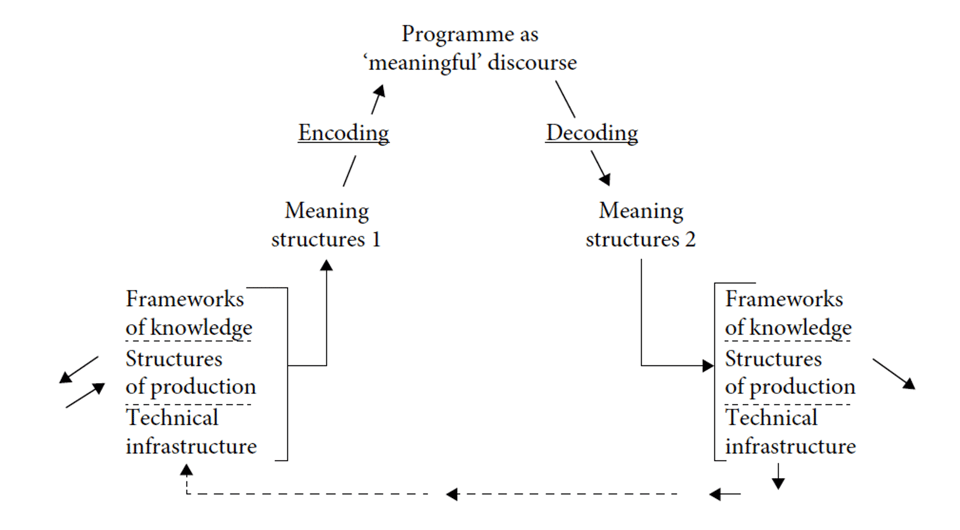

Hall wanted to demonstrate how audiences could exert agency over the messages they received. To demonstrate this, he created a new model for communication, which you can see above.

At its core, this is still a sender→message→receiver model, with major additions. On the left is the sender position. Hall emphasizes that no sender is without bias (that would be their “frameworks of knowledge”). Crucially, he acknowledges that nobody becomes a sender without access to power. In the case of television, they must have the means to purchase “technical infrastructure,” which in the case of TV would be a studio and broadcasting apparatus. They also need connections to the “structures of production,” including government permission to carried on the airwaves (Hall was in England, where the BBC ruled TV), as well as money to pay for talent and production costs.

Once the sender has all of that, they now figure out what to say by interpreting the world around them (“meaning structures 1”). Obviously, this interpretation is shaped by all those fancy things they already have as senders. Next, they engage in “encoding,” turning their ideas about the world into a slick, scripted TV show or news segment. Encoding is a complex process that involves discourse, technology, and access to the airwaves.

The message, or what Hall calls “the programme as ‘meaningful’ discourse” is the end result of this long process of encoding, which converts reality into a media product. He is careful to call this message “‘meaningful’ discourse” with those ironic scare quotes because he wants to remind us that this message is not neutral.

Here’s where things get interesting. Notice that the receiver side of the diagram is just as complex as the sender. To “decode” a message, the receiver actively discovers its meaning by subjecting it to interpretation (“meaning structures 2”). And that interpretation is dependent on their access to power as well. Are they watching it on a TV in their house, in a prison, in a school? What do they know about the broadcast topics before watching? And do they have connections to the “structures of production” to craft their own response to what they see? Answering these questions tells us something about how they will analyze the message.

No receiver is exactly the same, and therefore the meaning of every message changes depending on who receives it.

In other words, there is no clean sender→message→receiver flow. Instead, receivers will always mangle, distort, ignore, and repurpose the message. Plus, the message is not neutral; it emerges from powerful social systems and discourses that shape its encoding.

The important thing is that Hall’s model describes how we, the audience, have the power to change the meaning of the stories we receive. By analyzing the codes in our media, we gain control over meaning itself. Here’s how that works.

The Three Positions of the Decoder

In his autobiography, Hall wrote:

Identity is not a set of fixed attributes, the unchanging essence of the inner self, but a constantly shifting process of positioning…identity is always a never-completed process of becoming — a process of shifting identifications, rather than a singular, complete, finished state of being.

He’d learned this from decades of living as an outsider on two islands — England and Jamaica — always uncomfortably aware of how colonial discourse was shaping the way people saw him. But he also learned that he didn’t have to buy into their perspectives. He could see his identity in a different, ever-changing light. And he brought that realization into his understanding of how audiences decode media messages too.

Hall proposed that there are three basic positions adopted by receivers of media messages.

The first is the “dominant” or hegemonic position. This position is often occupied by media professionals, senders, and other creators. It views the messages received in pretty much the same way the senders do, as natural, inevitable, taken for granted, or legitimate. To put it in today’s terms, people who watch FOX News and believe everything they hear are performing a “dominant” reading or decoding of a message.

Most of people occupy a “negotiated” position when it comes to our media. This means we acknowledge the “truth” of the dominant discourse, but with lots of contradictions and exceptions. For example, an Amazon warehouse worker might watch a news story about Amazon’s earnings and think capitalism is great — but also believe at the same time that they should organize a union. Or a person in Minneapolis might watch a TV show about urban violence and believe that crime is a growing problem, but still assert that we shouldn’t use police to solve it.

Like I said, this is where most of us sit when we consume media. We get sucked into the story, but we still retain a degree of skepticism about parts of it.

Though Hall wouldn’t have known about this in 1973, fanfic can also be a kind of negotiated reading. It allows receivers to recast Captain American and the Winter Soldier as boyfriends, or make a version of The Phantom Menace with way less JarJar. There’s even Hamilton, which is basically real person fic about the United States’ founders, imagining them all as Black and brown. Fanfic allows receivers to enjoy a story by changing some of it to suit their interpretations.

Finally, there is the “oppositional” position. This is where Gramsci does a little dance in his prison cell, because he can feel the counter-hegemony rising. An oppositional decoding is when a receiver perceives the truth behind the discourse — the truth of power relations. It’s the moment when you’re watching a politician on TV say “freedom,” and you realize that the politician only means freedom for white, cisgender people. Or when you’re watching a supposedly wholesome teen comedy and realize that it’s incredibly racist.

In the classroom, I love to use this clip from 1980s sci-fi classic “They Live” to illustrate the experience of an oppositional reading. The premise of the movie is that lizard aliens are secretly running the world, keeping humans in line through coded messages in the media. But then, the underground resistance creates special sunglasses that reveal the truth about what our media is saying. Our hero, played by none other than wrestler Rowdy Roddy Piper, has just been given a pair of those glasses, and he goes for a stroll through Los Angeles.

His discovery — that the advertisements and news magazines in his mediascape are telling him to obey, to be heterosexual and make babies, to buy things — is ripped straight from the pages of a Stuart Hall essay. This scene represents Hall’s greatest hope: that through the use of critical theory and discourse analysis, we will see the codes and power relations that shape our media.

Hall teaches us that we don’t just absorb media without question. The audience has power, more than it realizes.

Hall connects the bottom of the receiver side of his diagram back to the sender side, creating a circuit that shows how media consumption feeds media production in a never-ending process. Implicitly, however, that process can be interrupted. An oppositional position can inspire people to exit the dominant media vortex and protest their political leaders, go on strike, or write stories that help build a counter-hegemony. Put in contemporary terms, an oppositional reading can stop the doomscrolling and inspire you to resist hegemony in the real world.

In one of his 1983 lectures, Hall said:

People have to have a language to speak about where they are and what other possible futures are available to them. These futures may not be real; if you try to concretize them immediately, you may find there is nothing there. But what is there, what is real, is the possibility of being someone else, of being in some other social space from the one in which you have already been placed.

Here he was talking specifically about the struggle for Black liberation in the 1980s, but he was also explaining how oppositional readings work in practice. Oppositional positions emerge when we look to the future, imagining different identities and communities for ourselves — ones that aren’t allowed or represented in the current hegemony.

We don’t need to burn the entire system of media codes down to build our opposition, though. As Hall says, there is no meaning without codes. The goal is to build new meanings, flexible ones that can change the way we do, and to replace the old discourses that imprisoned us.

Let’s do a media studies exercise!

Want to get started on your quest to ruthlessly critique the codes in everything existing? Let’s give it a whirl. First, pick a piece of media that you want to analyze — it could be a TV episode, a podcast, a song, a movie, a book, whatever. Now, try to run it through a Stuart Hall encoding/decoding diagram. Here are a series of questions to guide you.

The Sender

Who created this media?

What kinds of biases and preconceptions did they bring to the project?

What kinds of technologies and social connections did the sender need to get their message out there?

If the sender put it out on social media, think about who owns the social media platform and what their biases might be, too.

To think about encoding, ask yourself how the message is presented and packaged. Is it fictionalized? Are there intense edits? Is it described talking-head style like a news show? Are certain kinds of people or brands used to sell the message?

The Message

What does the sender intend for the message to say?

Can you identify any discourses that are contained in the message?

The Receiver

Now it’s time to tackle the receiver side of the diagram. This is where you think about how you, the audience, perceive the message.

What does the message mean to you personally, or as a member of a specific community?

Are there parts of the message you agree with or enjoy, and parts you’d rather ignore?

What kind of technology did you use to receive the message? Did it affect the way the message looked or felt? (You can discuss image/sound quality, sure, but also consider how comments, ratings, or other social interactions change your perception of the message.)

Did you bring any special knowledge to your understanding of the message (i.e., are you a fan of the sender, or an expert on some aspect of what the message is about)?

Would you change the message to make it better, more accurate, or just more fun? How?

Is there anything about the message that strikes you as simply wrong or unjust?

Go forth and decode wisely!

Stay tuned for my next media studies newsletter, where we’ll talk about media genres. If you’d like to prepare, please watch the movie Crazy Rich Asians, which I’ll be discussing in some detail.

You just read issue #36 of The Hypothesis. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.