Psyops are everywhere, but not in the way that you might think. Here is a quick-and-dirty guide to recognizing these mind-warping weapons in the wild.

As I discovered while researching my new book Stories Are Weapons, psychological warfare became a professional industry in the early twentieth century, modeled in part on the new field of public relations. The basic structure of an American psyop is cobbled together out of advertising techniques, pop psychology, and pulp fiction tropes. Using insights gleaned from these sources, the military spent the early years of the 20th century figuring out how to craft messages that can hurt, demoralize, and distract you.

Then something terrible but predictable happened. Just as military equipment was transferred to civilian police forces during the 1990s, psyops found their way into the arsenals of culture warriors today.

Unlike bombs, however, psyops can be dodged. Once you know what to look for, your brain can treat this cultural ordinance exactly the way your spam filter treats e-mails about CrYpT0 InVeStMeNt$ – it will throw them in your mental trashcan unread, so that you can focus on constructive information.

So, how do you distinguish between a psyop – a weaponized story – from other kinds of communication? Walk with me through these three simple steps.

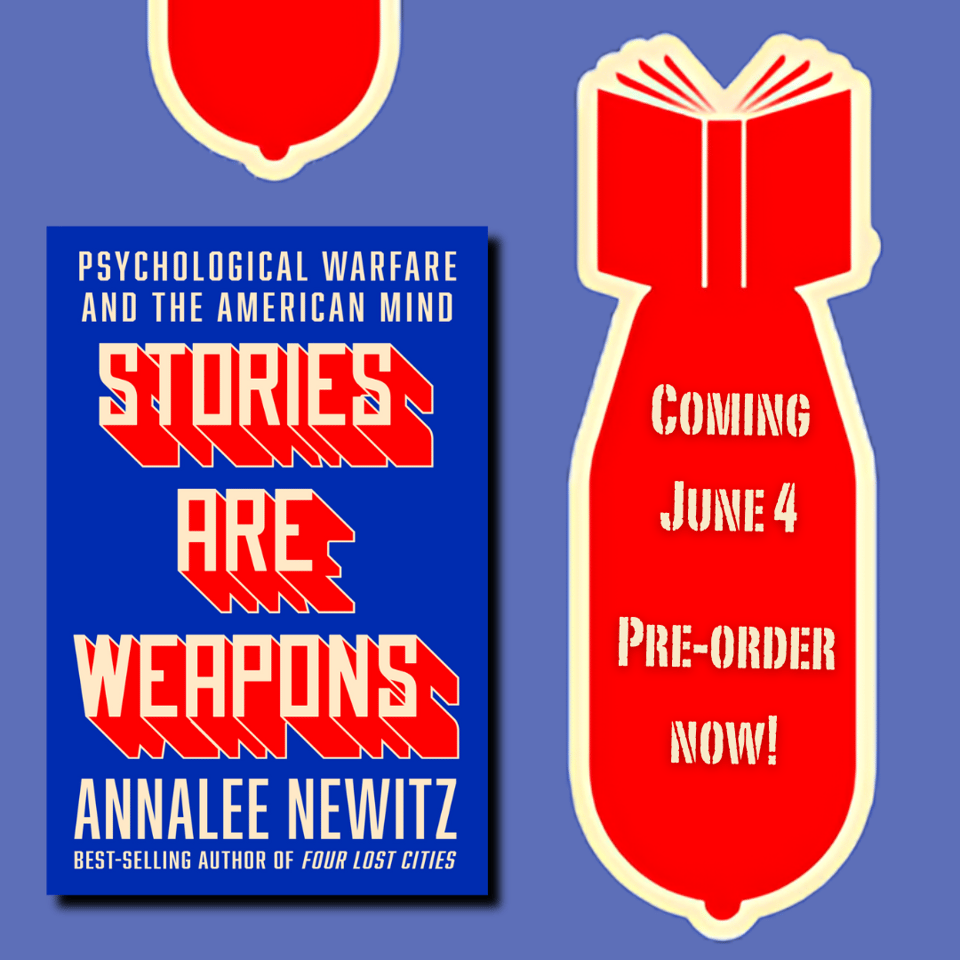

Did you know? Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind comes out in less than a month, and that means it’s pre-order season! More than ever, bookstores look at pre-orders as a way to figure out which titles they should stock – this is especially true of the monster stores like Amazon, whose algorithm promotes books based on pre-orders, but it’s also an indicator that indie bookstores look at too. So if you’re thinking of picking up a copy of Stories Are Weapons, smash that pre-order button now. You can even order signed and personalized copies from my local indie, Green Apple Books!

Step One: Did somebody say “anti-American”?

Pay attention to media messages that paint groups of American people as foreign, or somehow not quite “real” Americans. You can see this currently in stories about student protesters being “anti-American,” and in rhetoric that frames immigrants as “foreign born” aliens.

My book deals with the long history behind this rhetorical tactic. During the 20th century, the U.S. government used it to justify firing hundreds of LGBT people during the Lavender Scare. Senator Joseph McCarthy claimed that they were too easily seduced or blackmailed by foreign influences. In the late 19th century, Jim Crow laws forced Black Americans to live in what was essentially another country, with separate facilities and housing from white Americans. This setup made it easy for the government to frame Black people as threatening outsiders who shouldn’t be permitted to vote.

Even earlier, this kind of rhetoric was used against the people in thousands of Indigenous nations. Two centuries later, we still hear agitators and pundits trying to undermine their American compeers by claiming that they are not truly American.

There is a single, stark reason why this tactic is so often deployed. Psyops are weapons developed by the military, intended for use on a foreign enemy. Painting any group of people as “foreign” is a way of declaring that they are legitimate targets for psyops. Culture warriors want to pit groups of Americans against each other, inciting us to go to war with ourselves.

Step Two: Have you heard the one about deadly venomous snakes?

To recognize a psyop, it’s useful to read military manuals devoted to psychological warfare. I immersed myself in the work of Paul Linebarger, the Army intelligence operative who wrote the first U.S. guide to psychological warfare in the late 1940s. (You can read about him in my previous newsletter.) Then I worked with an Army PSYOP instructor, who shared a declassified PSYOP manual with me and taught me how special operations soldiers are trained to conduct influence campaigns today.

One of the throughlines between psyops in Linebarger’s time and now is that they are full of lies, wrapped around one or two nuggets of truth. A great example is this simple leaflet from World War II, dropped on U.S. troops in the Philippines by the Japanese. It’s designed to look like a warning from the U.S. Army about “deadly venomous snakes.”

Of course there are snakes in the Philippines, so there’s your bit of truth. If an American soldier found this leaflet, however, their commanders would deny (rightly) that it was legit. Then this soldier might start wondering if there was some kind of cover-up, and perhaps their commander was knowingly sending them into the jungle to die. Psyops-level lies are designed to destabilize an enemy, to make them doubt themselves and their compatriots, and to convince them that their country’s institutions are untrustworthy.

When psyops enter culture wars, you start to see lies structured like this snake “warning.” They don’t just misrepresent a specific situation; they aim to undermine an entire system of beliefs. When right-wing groups warn about malfunctioning voting machines, for example, the lie goes beyond the machines themselves. It is an attack on the U.S. voting system.

Step Three: You cannot communicate with someone who says you should be dead

Along with lies, psyops often contain violent threats. Again, this is an explicit part of military training in PSYOP development. That’s because the message in war often boils down to “surrender or die.” This is the easiest kind of psyop to recognize when it pops up in your everyday doomscrolling. When somebody tells you to kill yourself, they are obviously deploying weaponized language. There is no way to argue with “you should die.” It is not a political position; it is a statement of intent do do harm.

That said, there are ways that violent threats enter so-called rational political debate in more subtle ways.

Take, for example, the way reactionary politicians use the word “groomer” to describe LGBT people. “Groomer” is a term that comes out of law enforcement, and is used to describe the behavior of an adult trying to gain the trust of a child they intend to harm or abuse sexually. Calling someone a groomer is essentially calling them a criminal who should be incarcerated and have their civil liberties taken away. In Stories Are Weapons, I trace the origin of the “groomer” epithet back to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s 1930s campaign to root out “sex criminals” – his favorite term for LBGT Americans.

Criminalizing a group of people is another way of threatening them with violence and death. Calling for the imprisonment of any group — whether immigrants, student protesters, or trans people — is not the opening gambit in a debate. It is a way of shutting down discussion. It is, in short, a psyop.

Recognizing psyops is one way to defuse them. Instead of engaging with people and organizations hurling weaponized messages at you, do anything else. Write a letter, sit in a garden, talk to a friend, play a game, listen to music, or seek out information that isn’t laced with lies and threats. We won’t end this culture war by manufacturing better weapons. We must refuse to fight. We must rebuild our public sphere, not nuke it from orbit.

In Stories Are Weapons, I report on people and organizations who are trying to end culture wars by doing just that. They’re telling new kinds of stories, protecting our histories in archives, and changing the way social media connects us with each other. They’re also trying to repair the harms and traumas caused by this often-unacknowledged war. Check it out on June 4, or pre-order a copy today! Also, I’ll be on book tour this summer, so come out to see me and say hi!

Two Books to Think With

Recently, a group of rebel historians in Texas broke away from the state’s historical society to found a new organization, the Alliance for Texas History. It’s a great example of why history matters deeply in culture war, and has done for centuries. And it reminded me of one of the books that influenced my thinking a lot: Ojibwe historian Jean M. O’Brien’s Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. It’s about how New England historical societies in the 19th century produced boatloads of amateur-written books about their towns that all made a weirdly similar claim. Somehow, these histories claimed, all the Indigenous people who used to live in the area had disappeared or gone extinct (after kindly giving their land to the English, of course). Even weirder: Some of these same histories would describe groups of Indigenous people who currently lived in town. So were the Indians gone or not? Obviously they were very much not gone, but historians were trying to make them invisible.

I spoke with O’Brien early in my research, and she told me this was part of a larger cultural trend of white settlers conceiving of U.S. history as a story where Indigenous people conveniently “disappeared” — it was history as psyops, and it went right alongside actual genocides happening in the West. O’Brien made me see how culture war and total war work together, especially on the local level. These books may have been little amateur histories, but they influenced their communities and justified the United States’ ongoing wars with western Indigenous nations.

Another book that I kept thinking about as I wrote was one that strongly influenced me when I was a young cultural critic: the late UC Berkeley political scientist Michael Rogin’s Ronald Reagan the Movie, and Other Episodes in Political Demonology. He was responding a moment in U.S. history that is almost as surreal as our own. America’s first Hollywood celebrity president, Ronald Reagan, merged fiction and reality in his political rhetoric to usher in a new era of extreme conservatism. Rogin paired that event with others in the nation’s past, when storytelling became a surrogate for facts in government policy. Acerbic and well-observed, this book is a reminder that the United States has a long history of selling its policies to the public using fantasy and fabulation.

Stuff I’ve been working on lately

Just in case you need more psyops, I wrote an article for The Atlantic about how science fiction influenced psyops, and why conspiracy influencers often sound like they are regurgitating bad science fiction.

I co-host the Our Opinions Are Correct podcast every other week with Charlie Jane Anders, and our latest episode is about how stories get weaponized! Plus we answer some very silly questions from our listeners.

You just read issue #30 of The Hypothesis. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.