One of the great mysteries contemplated by everyone from top executives in the entertainment industry, to lowly culture critics, is why people are willing to pay money for certain kinds of stories. Especially when so many of those stories are essentially the same narratives, with slight variations. In my letter today, we'll be exploring one powerful reason why people are willing to shell out to experience the same kinds of content, over and over.

In the two previous letters from this series about media studies, I introduced you to the ways researchers study media, and we explored the analytical breakthroughs made by one of the founders of the discipline, Stuart Hall.

Now we’re going to start analyzing media content, by looking at how we divide stories up into genres like “horror” and “science fiction.” We’ll take a deep dive into the romance genre, and investigate how we use fictional stories as a self-soothing device — for better and for ill. And yes, there will be a media studies exercise for you at the end!

(Spoiler alert: I’ll be talking about the movie Crazy Rich Asians, and there will be a couple of spoilers for this movie from 2018.)

Reader Response Analysis

One of the best early studies about why people love repetitious stories is Janice Radway’s 1984 book Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature. It’s a classic example of the “reader response” method of analysis. Like Stuart Hall, Radway wanted to investigate how audiences felt about popular media, and to center their experiences. She decided to focus on romance novels because it seemed that nobody would take them seriously, even though they sold incredibly well. Romances were derided as “trash” by humanities scholars, and “sexist” by feminists. They were, in short, guilty pleasures that people weren’t supposed to dignify with scholarly research.

And yet, Radway had a hunch that fans of the genre weren’t just fools or dupes. Like Hall, she believed that readers could take a negotiated or oppositional stance toward a narrative, picking and choosing what they wanted to get out of it, rather than being brainwashed.

But to learn what readers were getting out of romances, she needed to find fans and talk to them. Radway started her work in the late 1970s, long before online fandom was a thing. So she went in person to visit with a group of romance readers in the midwest who all shopped at the same bookstore, run by a woman named Dot. Dot had accumulated a small but loyal following for publishing a regular newsletter reviewing the latest romance books. Today, Dot would probably be on BookTok. Back then, she was a nice lady behind the counter at the bookstore, who knew her customers well enough that she could always recommend another romance they would like as much as the last one.

As Radway got to know Dot and her customers better, she found that they turned to romance novels for reasons that none of the critics of romance had understood. They were choosy about the stories they liked, as discerning as literary scholars would be about so-called great books. They also talked about how the books filled emotional needs they couldn’t get from their families. Over a period of several months, she interviewed several romance readers and gave them surveys about what they considered a good romance book.

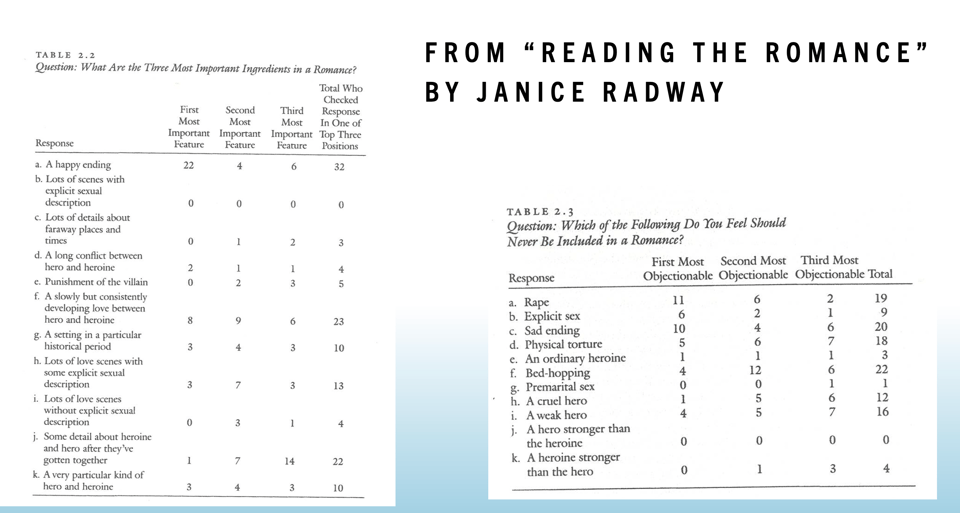

When I was teaching media studies last year, my students read chapter two of Reading the Romance, where Radway explains her research methods. Above, you can see one of my favorite charts from that chapter, where Radway lists her interview subjects’ favorite and least favorite elements in romance novels. Not surprisingly for anyone who loves romances today, two of the most beloved ingredients were “a happy ending,” and a slow-burn relationship. The least-liked ingredient was a “sad ending,” closely followed by rape. In follow-up interviews, she asked the readers to clarify how the books fit into their lives, and we’ll talk more about that below.

Once she understood what people loved (and hated) about romance stories, Radway wanted to know what made women buy books with these same plot elements, again and again. What she found gives us tremendous insight into the lure of romance. It also gives us a framework to understand the lure of all genre fiction, from reality TV to horror.

The paradox of genre

First things first: what the heck is a genre? Put simply, it’s any group of stories that share the same basic plot structures, with similar kinds of characters, tropes, and settings. Common genres include horror, drama, science fiction, romance, action, comedy, documentary, reality, and memoir. There are also tons of subgenres, like romantasy, horror-western, and comedy-drama. Even literature and fine art are essentially genres.

A genre is also a vibe: we know it when we feel it. But we know when we don’t feel it too. If you’re into romance, and the supposed romance book you just bought has a sad, rapey ending, you will likely throw that book across the room.

By definition, fans of genre consume very similar pieces of content repeatedly. Radway calls this the “paradox” of genre. Each story needs to feel different, without ever diverging from the basic formula. Together, the stories within a genre create a kind of alternate world that audiences can return to with each new piece of content. The more genre fiction they find, the more time they can spend in that world.

The question then becomes, why do certain genre worlds work for some people? What is the genre giving to those people that makes them pay to return?

Compensatory Fantasy

What Radway suggests is that genres offer a compensatory fantasy, or a fictional narrative that compensates for a perceived deficiency in reality. To truly understand what draws people to a genre, we need to understand what it’s compensating for in their real lives.

To start, it’s easy to see why happy endings would be so important to romance fans. Few people experience their relationships as perfectly happy forever. But hey — for just a few bucks, you can imagine yourself in a relationship that’s completely fulfilling. That’s the lure on a very basic level. When our lives are less than exciting, or downright awful, at least we can return to our happy places in stories.

But of course, there’s more at stake than merely wishing for a happy ending.

Let’s find out what those stakes are by applying Radway’s analysis to Crazy Rich Asians, a wildly popular romantic movie based on a novel by Kevin Kwan.

In the course of her research, Radway discovered that many of her interviewees were mothers and housewives, who spent all their time caring for other people and doing domestic chores. They told her that reading romance novels gave them the feeling of being nurtured or pampered — a feeling often lacking in a caregiver’s life. This feeling was heightened when the main character was loved by a man who genuinely empathized with them and understood them.

Crazy Rich Asians is a romance about a woman named Rachel, an economics professor in the U.S., who is dating Nick. Though they’ve been dating for over a year, Rachel doesn’t know that Nick is from one of Singapore’s wealthiest families. She only finds out when he takes her home to meet his family, and she’s suddenly plunged into a maelstrom of billionaire drama. She has to deal with the fashion demands of lavish parties, Nick’s vengeful ex, and — scariest of all — her future mother-in-law Eleanor, who hates her.

After being taunted horribly by Nick’s ex at a party, she vents to Nick. Pay attention to the way he responds in this scene.

He’s nurturing, he listens to her, and he’s incredibly sweet. Nick is the perfect romantic lead.

Still, a compensatory fantasy doesn’t work unless it also acknowledges the troubles that the audience is trying to escape. In this scene, we see Nick at a bachelor party with his male friends, one of whom scoffs at Nick’s relationship with Rachel in extremely degrading terms. With no money and no family name, he says, she’s worthless.

“Are we in some kind of fairy tale story that I don’t know about?” he asks Nick. “Did you find a shoe at midnight and jump into a pumpkin?” He’s threatening to puncture the perfect fantasy, by acknowledging that happy endings are a “fairy tale.”

Another one of Nick’s friends responds by joking that the only thing Rachel has to offer are “small tits.” This insulting comment speaks to another point that Radway makes in her book, which is that romances help women cope with misogyny, and the fear that men will be violent and mistreat them. This moment in the film reminds us exactly who and what the romantic fantasy is compensating for.

Nick takes Rachel’s side, of course, defending her to his friends and his mother. He is the perfect romantic lead, after all. And Rachel gets her happy ending.

What about the audience, though? Where does this compensatory fantasy leave us, when the movie ends or we close the book?

Radway believed that Dot’s bookstore group used romance books to escape from patriarchy for a little while, to feel nurtured, before going back to housework and child care. So women were driven to these novels to get relief from patriarchy, and yet the stories always ended with patriarchy intact. It wasn’t a bad hypothesis. At that time, in the early 1980s, nearly all romance stories ended with happy patriarchy — i.e., heterosexual marriage to a man with more power than the woman.

It seemed to Radway that the romance genre acknowledged readers’ anxieties about men, only to end by suggesting men as the solution. There was a tautology to these stories, and the only way to get relief from it was to consume more of them, to get back into the fantasy of being understood and cared for.

Narrative Containment

Media studies researchers sometimes describe this predicament as “narrative containment.” Narrative containment is what happens when a story suggests that our lives could be radically different — full of men who support independent women, for instance — only to wind up acclimating us to the status quo. Narrative containment is a way to suggest that we can’t solve systemic problems. Instead, we compensate for them with fantasies that acknowledge those systemic problems before sweeping them under the rug.

Bearing this in mind, it makes sense that people would need to return to the genre worlds of their choice repeatedly. The only relief they get is from stories. And those stories reassure them that there is nothing they can do to change reality. Their fantasies keep them contained, rather than inspiring them to act.

Radway thinks that the narrative containment in romance novels takes the form of patriarchy, but a lot has changed in the romance genre since she was writing. There are plenty of romances with LGBT2S characters (Red, White, and Royal Blue, anyone?), and female protagonists generally have jobs or other fulfilling activities outside their romantic relationships. Anyone who has ever read an Alyssa Cole or Rainbow Rowell romance knows that patriarchy does not win at the end.

Similarly, Crazy Rich Asians features an independent heroine with a great job and a full life. It would be difficult to argue that patriarchy is her main problem, though of course we did see misogyny haunting the story earlier.

So how does narrative containment work in Crazy Rich Asians? Throughout the movie, Rachel struggles to deal with threats from the women in Nick’s life, especially his mother. In a sense, she’s dealing with matriarchy, not patriarchy. But it’s more than that. Most of the anxieties expressed in Crazy Rich Asians are about class. Eleanor cannot accept that her son wants to marry a woman whose mother was unmarried and from a working class family. Nick’s friends make fun of Rachel because she’s basically a pauper compared to them. And yet Nick’s attachment to her seems to promise a world where class and family status don’t matter. He sees her as his equal. The compensatory fantasy here isn’t an escape from patriarchy; it’s an escape from capitalism.

Now, where do we find narrative containment happening in the movie? We see it in a brief scene at a party, near the end of the film when Nick has proposed to Rachel. In this scene, the focus isn’t on the couple. Instead, we see Eleanor exchange a meaningful, almost romantic glance with Rachel. It seems that Nick’s mother has acknowledged and accepted her.

And that suggests Rachel may soon have a family name and unimaginable wealth to go with it. The film deals with class anxieties by containing them in a narrative about joining the ruling class and enjoying it.

Genre stories don’t provide a solution; they just help you escape your problems for a while before delivering you back to the place where you started. That’s why you have to keep buying more.

I should note that Radway’s work isn’t a condemnation of genre, nor does she think it’s wrong for people to get enjoyment out of compensatory fantasy. I don’t feel that way either — in fact, I gave an entire TED talk about how escapist fantasies can inspire us change our real-life conditions. Still, there is value in understanding one possible reason why genre stories make us feel so good — and why we want to return to fantasy worlds so much that we’re willing to pay for them repeatedly.

A coda: Memory Editing as a Service

Let’s conclude with a slight detour into a common trope from the science fiction genre: memory editing machines. I would argue that these devices, which fuel the plot of several popular stories, are a way of dramatizing how compensatory fantasy works.

We see this very clearly in the classic 1990 movie Total Recall. Below, in an advertisement from within the film, we see shady corporation Rekall promising to implant memories in your mind, to make up for what is implictly a shitty life full of work, bills, and physical pain. A good romance novel is a bit like an implanted memory, which lives happily in your head as a counterweight to real-life troubles.

Fourteen years later, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind toyed with this same idea. Here, in another fictional ad, the pitch from Lacuna Corporation is that they’ll erase unwanted memories rather than implant desirable ones. The sales pitch is ultimately the same: we pay to change our memories, and that makes life more bearable.

The latest iteration of the memory-alteration trope comes in the series Severance, currently in its second season. In this ad from the series, below, the fictional Lumon Corporation touts a high-tech procedure that splits consumers’ personalities in two, hiding their work memories in an inaccessible region of their minds. The result is that participants, called “outies,” never remember the drudgery of work. But the Lumon process also spawns an “innie” self, a person who has no memories of anything but work.

By personifying all the memories we want to forget with the innies, Severance reminds us of the price we pay when we invest entirely in compensatory fantasy. The more we use stories to forget the hard parts of our lives, the more willing we are to subject ourselves to demeaning, horrific conditions.

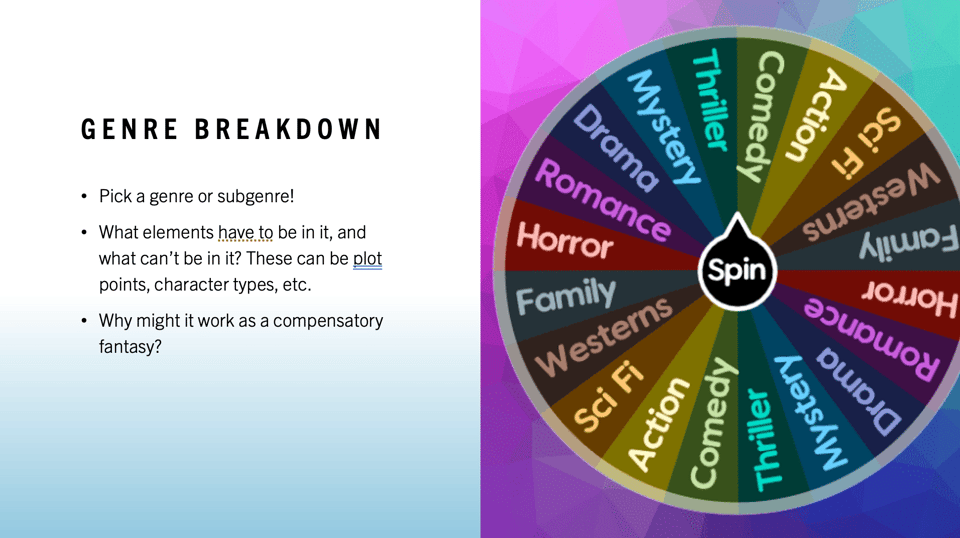

Let’s do a genre exercise!

Want to analyze a genre as compensatory fantasy? Now’s your chance.

First, pick a genre or subgenre.

Ask yourself what elements have to be in it, and what can’t be in it. (These can be plot points, character types, or anything else.)

Now, ask yourself how it might work as a compensatory fantasy. What anxieties or fears does it raise from the real world? How does it compensate for them?

Other stuff:

I have a book coming out in August! It’s called Automatic Noodle, and it’s about a group of robots who open a noodle restaurant in San Francisco after a devastating war has wrecked the city. If you pre-order now from your favorite bookstore, it makes a huge difference!

I’m writing a series of columns for New Scientist about the history and future of futurism. The first three installments are up now, and you can read them by creating a free account on New Scientist’s website.

And of course you should listen to Our Opinions Are Correct, the podcast I co-host with the luminous and brilliant author Charlie Jane Anders! Every two weeks, we talk about science fiction, science, and society, with interesting guests and weird topics. Our latest episode is about recent movies featuring forced feminization and cute robots (not necessarily at the same time).

You just read issue #37 of The Hypothesis. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.