I've spent the past three years researching and writing a book about the history of psychological warfare in the United States. It’s called Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind, and it comes out on June 4. The subject crept up on me, and not for the reasons you might think.

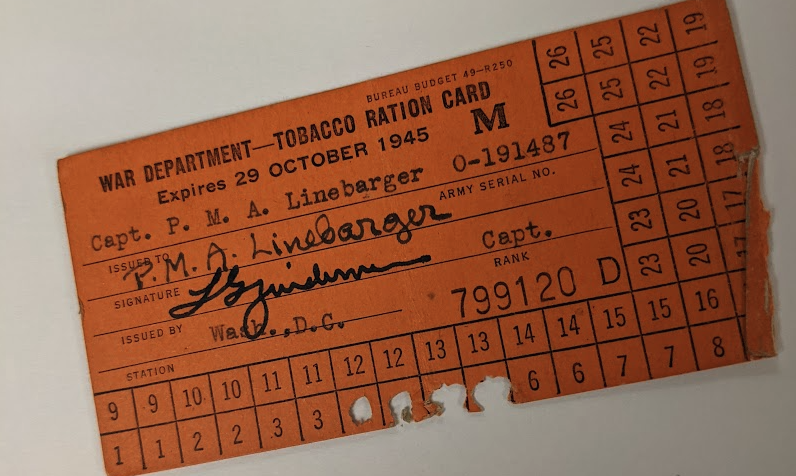

It all started over a decade ago at a science fiction convention in San Diego. I was talking to the writer Eugene Fischer about obscure writers that we loved. He mentioned Cordwainer Smith, a mid-twentieth century author who had written about human-animal hybrids of the distant future who led a revolution against their cyborg masters. It sounded amazing and weird, and I made a mental note to pick up some of Smith’s work. It was only later that I discovered that Cordwainer Smith was the pen name of Paul Linebarger, an intelligence operative who wrote the first Army manual devoted to the practice of psychological warfare in 1948.

I had to know more. So I started digging, and what follows is some of what I found. I was only able to cram a few of these gems into my book, so I've got a treasure trove of stuff here that I've been dying to talk about.

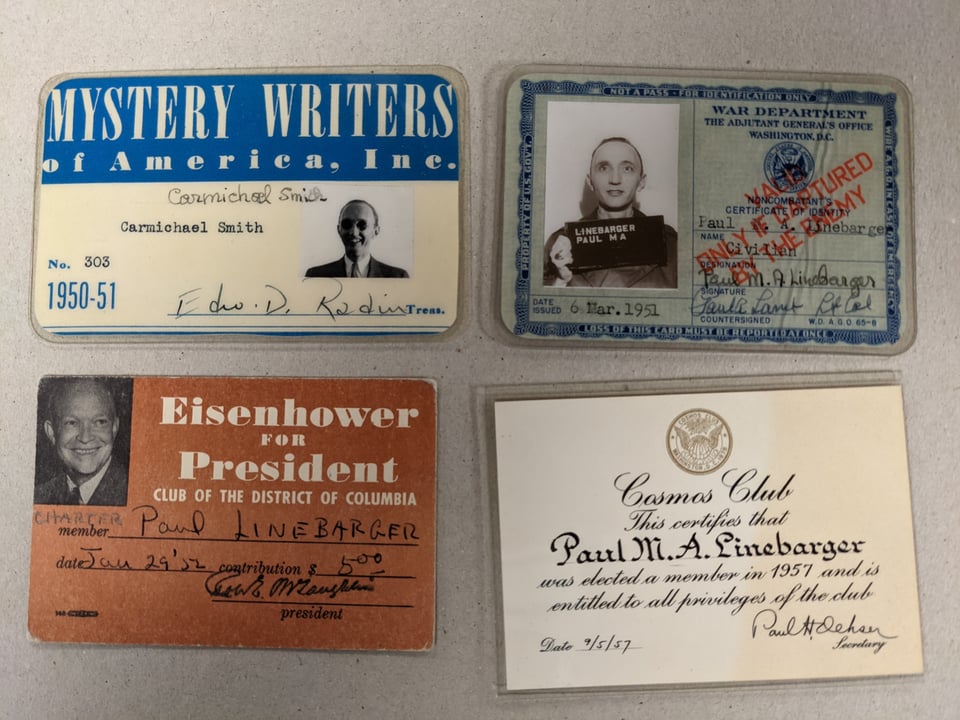

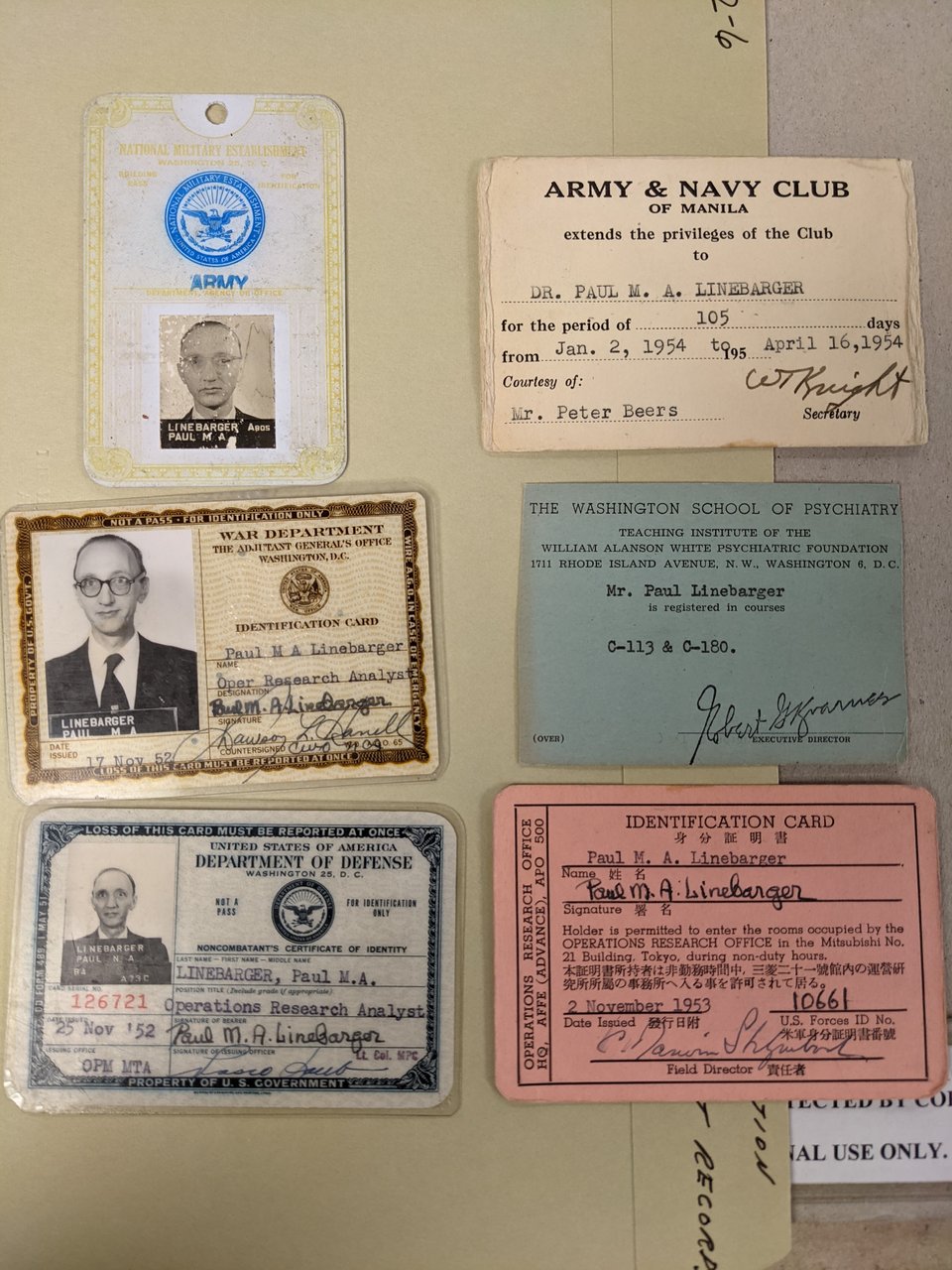

Linebarger’s father was a judge in the Philippines who became a devoted follower of Chinese nationalist Sun Yat-Sen. As a result, the young writer spent long stretches of his childhood under the tutelage of his godfather Sun Yat-Sen in China, learning statecraft from his father’s circle and Mandarin in school. He grew up with two names: 林白乐 (Lin Bai-lo) and Paul Linebarger. As an adult, he published science fiction as Cordwainer Smith, realist fiction under the name Felix C. Forrest, as well as a spy novel and an unpublished pop psychology book under the name Carmichael Smith. As a professional psywarrior, he worked to overthrow the Communists in China – not for the glory of America, but to continue the nationalist project of his mentor Sun Yat-Sen.

Now declassified, Linebarger’s Psychological Warfare is available from a number of print-on-demand publishers. I ordered a copy online, and read it alongside a collection of Cordwainer Smith stories called We the Underpeople. I couldn’t believe the same person had written them. This guy who wrote about subversive cat women and robot cities and weapons made from angry psychic weasels and mind control sex between people who are literally floating naked inside a chamber of flames – he had also codified the U.S. military’s approach to psyops at the dawn of the Cold War? Really??

I’m not the first person to ask this question using italics and lots of question marks. A miniscule cottage industry of writing about Linebarger’s life explores whether he was secretly delusional, or perhaps dropping subversive messages in his stories. Gary K. Wolfe, a literary critic who has written quite a bit about Linebarger’s fiction, told me that some fans thought the author had to be a time traveler because his futures felt so vivid and bizarrely detailed. There are even questions surrounding the people who study Linebarger. Alec Nevala-Lee, author of Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, said that he’s heard a lot of wild speculation about UC Davis psychology professor Alan C. Elms, who spent decades writing a biography of Linebarger, but never published it for mysterious reasons.

My point is that Paul Linebarger was a psyop specialist whose life history reads like a psyop. It makes you want to do your own research, as the conspiracy influencers say. I couldn’t stop thinking about Linebarger, but it wasn’t because I thought he was some kind of time traveling superspy. His work made me realize how much American propaganda strategies owed to science fiction.

Eventually, I followed my curiosity to the Hoover Institution Library & Archive at Stanford University, where Linebarger’s papers are kept alongside his father’s.

This and the image below are from Linebarger’s personal diaries, which he kept between the ages of 10 and 16. Above is a note from October 17, 1926, when he was 13 years old. “I love Shanghai. Paradise!!!” he scrawls. “I don’t want to go away. Never! Never!! Never!!!!!!” He had just spent two years in China with his family, and was very enthusiastic about travel.

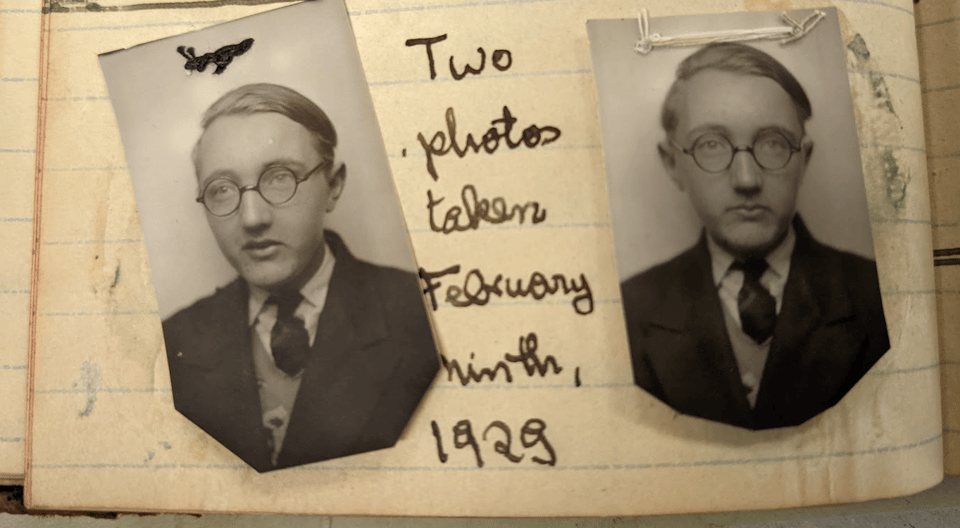

Two photos taken February ninth, 1929. Linebarger was 15 years old, and was in his first year at George Washington University.

These are some slips of paper and pictures he kept tucked into the front flap of his teen journal: Chinese language practice, a picture of himself on a ship with a group of his father’s compatriots and Sun Yat-Sen followers, a picture of the Horsehead Nebula cut out from a magazine, and a list of women’s names (likely girls he’d had crushes on – his journals are full of urgent romantic commentary). It was wild to peer into the baby mind of a psywarrior, to see how closely his childhood interests aligned with his adult profession. He approached science fiction and international policy as two strands in the same project: Both were about explaining alien civilizations to each other, with a very specific goal in mind.

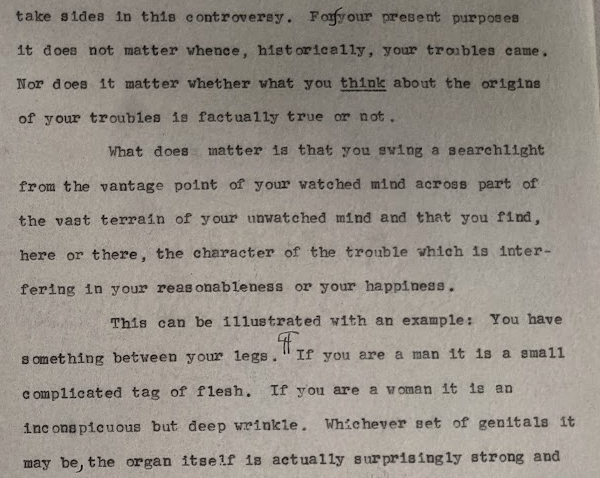

The fragment of typewritten manuscript above is from a book called “Conversations with Sun Yat-sen,” which he co-wrote with his father in the early 1930s. It’s from the introduction, written exclusively by the younger Linebarger, when he was both a college student and an his father’s secretary, helping with policy and intelligence analysis for the Chinese nationalist government. He wanted to sow empathy for China among Americans, especially at a time when racist immigration policies and political ignorance had distorted many people's understanding of what was happening across the Pacific.

He writes: “China the Nation, in the mind of Sun Yat-sen, is the most difficult of all his principles to interpret to the Western understanding. Nationalism is so simple and intelligible a phenomenon when preached by Hitler and Mussolini that is seems impossible that any other doctrines should be nationalistic and yet run counter to the chauvinisms of the modern world.”

Linebarger goes on to describe Sun Yat-sen as something of a science fiction writer, teaching his people about alien worlds beyond China. “It was the duty of Sun Yat-sen to persuade a world that it was no world, but a nation; to persuade his fellow-countrymen that their customs and traditions were not the universal laws of reason, but only the peculiarly fine development of one civilization; to teach them that their world, whence patriotic and religious wars had long been banished, had to contend with a narrowing universe which had brought forth other worlds, fantastically different, upon the same globe.”

I had to know more about where this overlap between genre fiction and psychological warfare began. So I delved deeper -- reading histories, interviewing experts and practitioners -- and I found examples of U.S. psyops going back to the nation's earliest days. Two hundred years ago, propagandists were using narrative techniques borrowed from many kinds of popular storytelling: tabloid journalism, fantasy, cowboy stories, adventure tales, comedy, horror. This was a tradition that Linebarger had inherited from generations of Americans before him. In the nineteenth century, for example, popular Western dime novels inspired pundits who pushed "manifest destiny" as a policy. Newspaper accounts justifying the United States' wars on Indigenous nations often read like cowboy adventures set in an unclaimed, virgin land. Using the tropes of popular entertainment helped pro-expansionists sell settlers on the U.S. government policy of coercively relocating hundreds of thousands of people.

In World War II, Linebarger and many of his colleagues advised psywarriors to make their products resemble movies, pulp fiction, radio, and other forms of popular entertainment. They also studied advertising for hints about how to persuade reluctant adversaries, and imitated the language of scientists to make their lies sound trustworthy.

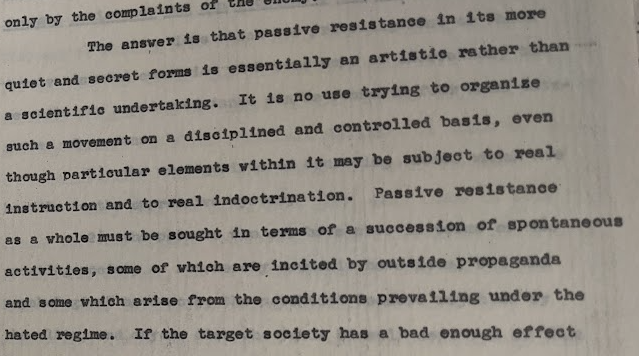

I think psyops specialists are often cast as secret agents who suppress dissent, cover up the truth, and push mindless conformity. But most of Linebarger's work focused on fomenting revolutionary movements. He wanted his work to inspire ordinary people who feared their struggles against Nazis and dictators were doomed. In 1950, he wrote an unpublished monograph about how to encourage "passive resistance," which he described as "obstruction to authority" that doesn't involve an organized military force. People in such a movement don't plant bombs, he wrote, but "their hostility to authority outweighs their fear of authority." He credited this form of resistance movement with challenging tyranny in Ukraine, China, Japan, and India.

He also compared it to art. "Passive resistance in its more quiet and secret forms is essentially an artistic rather than a scientific undertaking," he wrote.

He was right. Psyops are an unsung speculative art. Some are brilliant, and others are duds. But they are all attempts to create compelling, emotional stories that offer audiences a new perspective – and inspire them to take action.

Psyops are also, fundamentally, lies -- often with violent overtones. Still, the original 1948 version of Psychological Warfare concludes with a section about "psychological disarmament," where Linebarger imagined a world of psychological truths and peace. Border controls would be abolished, and the government would fund education and public parks, while also guaranteeing a free press.

As the Cold War escalated, however, he abandoned this serene vision. In the 1954 edition of Psychological Warfare, he explained that he had replaced the disarmament chapters with a section on the future of psyops. His implication was that psychological warfare would be permanent, with no ceasefire or peaceful resolution. And, as propaganda production grew more sophisticated, he predicted that more authors would join the cause. "The artistic and cultural aspect of writing is readily converted to propaganda usage," Linebarger wrote in the book's new conclusion.

Throughout his life, Linebarger kept journals of his travels. Often, he would jot down a sentence or two, describing the sounds of aircraft carriers or the way light glinted on the Nile at sunset. And sometimes, those notes showed Linebarger realizing that the United States had its own set of oppressive systems that ought to be resisted.

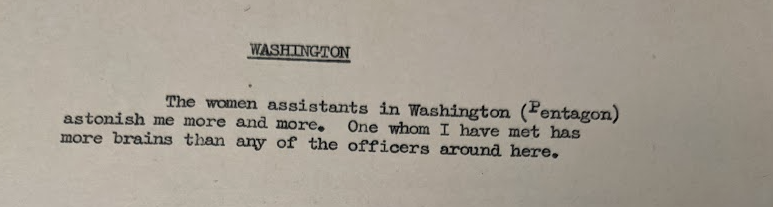

In an undated note from the 1950s, Linebarger noted: "The women assistants in Washington (Pentagon) astonish me more and more. One whom I have met has more brains than any of the officers around here."

Unlike most men in his profession at the time, Linebarger frequently acknowledged the contributions of women. Many of his major fictional characters are women, too -- including the heroes C'mel and D'joan, who lead resistance movements against the dictatorial Instrumentality, an interstellar government that looms over much of his work. According to his biographer Alan C. Elms, Linebarger had hoped to use the pseudonym Lucy Estes on his first two books, but his publisher convinced him to use a man's name.

I spoke to Linebarger's daughter Rosana Hart, who maintains a website devoted to her father's work. "I think he thought that women were superior to men," she told me. I wondered whether this feeling -- so out-of-step with dominant ideas about women in the 1950s -- might have fueled his urge to generate new identities for himself through writing. Maybe he was searching for a way to express an identity that was more fluid than the one the world allowed him.

After I talked to Hart, I kept thinking about Linebarger's fiction as a wrathful exercise in frustrated self-fashioning. There is an undeniable streak of cruelty in Linebarger’s sci-fi stories – he revels in describing intense mental and physical torture, and many of his characters die in gruesome ways. Hart told me that her father believed people should see the ugly side of humanity, in order to understand the truth about the world. When she was a little girl, he made a point of telling her about the horrific things people had done to each other in the wars he’d studied and experienced firsthand. “He would go into more detail about suffering than a child should have had to listen to,” she said.

No matter what Linebarger did, he was always trapped in a cold, liminal space between the worlds of China and the United States, propaganda and art. If he couldn't inhabit the world as it was, perhaps he could use his words to bash a better one into being.

With his book Psychological Warfare, he codified a form of creativity whose purpose is to persuade, but also to intimidate, demoralize, and mislead. He described psyops as an opportunity to aid the oppressed, but also a way to hurt adversaries.

This is the paradox at the heart of all propaganda. Unlike wild storytelling, psyops have a specific purpose: to become a weapon. Perhaps it is forged with the intention of bringing justice to the oppressed. And perhaps its emotional ammunition is aimed at the minds of the vulnerable. Either way, it is a weapon whose power cannot be contained. Like a gun or a tank, it can be transferred from the military into civilian life, exploding our domestic policies, school board meetings, healthcare access, and employment opportunities. And that is what Stories Are Weapons is about: how psyops designed for use against national adversaries became weapons in a culture war between people who live in the United States.

Pre-order Stories Are Weapons now!

You can pre-order Stories Are Weapons now from your local indie bookstore! If you'd like a personalized and/or signed copy, you can order it from Green Apple Bookstore (just write in the "info" field how you would like it personalized).

Pre-orders help tremendously, by sending a signal to stores and my publisher that people are interested in the book -- and that can lead to more exposure for Stories Are Weapons.

See me on my west coast book tour!

Mark your calendars and get your tickets now! Here's the schedule (more dates may be added later):

6/4: 7pm, Powell's Books in Portland (w/Dave Miller, host of OPB's "Think Out Loud")

6/6: Seattle Town Hall (w/Lindy West) -- ticketed event (link coming soon!)

6/13: Mechanics Institute in San Francisco (w/Alexis Madrigal)

6/18: 7pm, Berkeley Arts & Letters at the Hillside Club in Berkeley (w/Ed Yong) -- ticketed event

What I've been working on lately

I reviewed two fascinating books about surveillance for the New York Times: "The Sentinel State," by Minxin Pei, and "Means of Control" by Byron Tau. Comparing the high tech (and low tech) ways that China and the U.S. spy on their citizens is extremely instructive.

I have a new short story out in the glorious Uncanny Magazine! It's called "The Best-Ever Cosplay of Whistle and Midnight," and it's about what happens when the biggest worm cosplay convention on the planet Sasky loses its venue. Get ready for interspecies dramas, last-minute costume decisions, and a lucky encounter with a very silly cat who works as a bartender at THE TONGUE FORKS. This story is partly a response to the many people who read The Terraformers and asked me, "What happened to the worms after they were able to speak?" But it's also a standalone tale about what it's like to celebrate your body, no matter what form it takes.

Also, if you are feeling saddened by the rise in Comstockery in the States, just remember that I wrote a novel about time traveling feminists fighting Comstockers across the timeline to restore reproductive rights in America. Hell yeah!

My New Scientist column comes out monthly, and is now outside the paywall! Check out some recent columns on new ways of analyzing UFO sightings, why the Taylor Swift psyops stories are more dangerous than you think, the unregulated Utopian city that billionaires are secretly trying to build on Northern California farmland, and why trust and safety is the most important tech job you've never heard of.

And the amazing podcast that I co-host with Charlie Jane Anders, Our Opinions Are Correct, comes out fortnightly! Check out our recent episode on queer horror with guest Chuck Tingle, and our evisceration of the Turing Test with the help of AI researchers Alex Hanna and Emily M. Bender!

You just read issue #29 of The Hypothesis. You can also browse the full archives of this newsletter.