The Crime Lady: Watch Out, Buford

Dear TCL Readers:

The door on 2025 is about to close. It was a hard year for most everyone, and there were plenty of ups and downs for me, too. But I’m especially proud that Without Consent published to consensus acclaim (including best-of-year nods from Elle and Library Journal), and that I was able to fit in some personal milestones — a monthlong trip to Europe, singing Handel’s Messiah at Carnegie Hall — in the mix. 2026 promises equal or greater tumult, so might as well hunker down, slow the roll, and make art, the weirder the better.

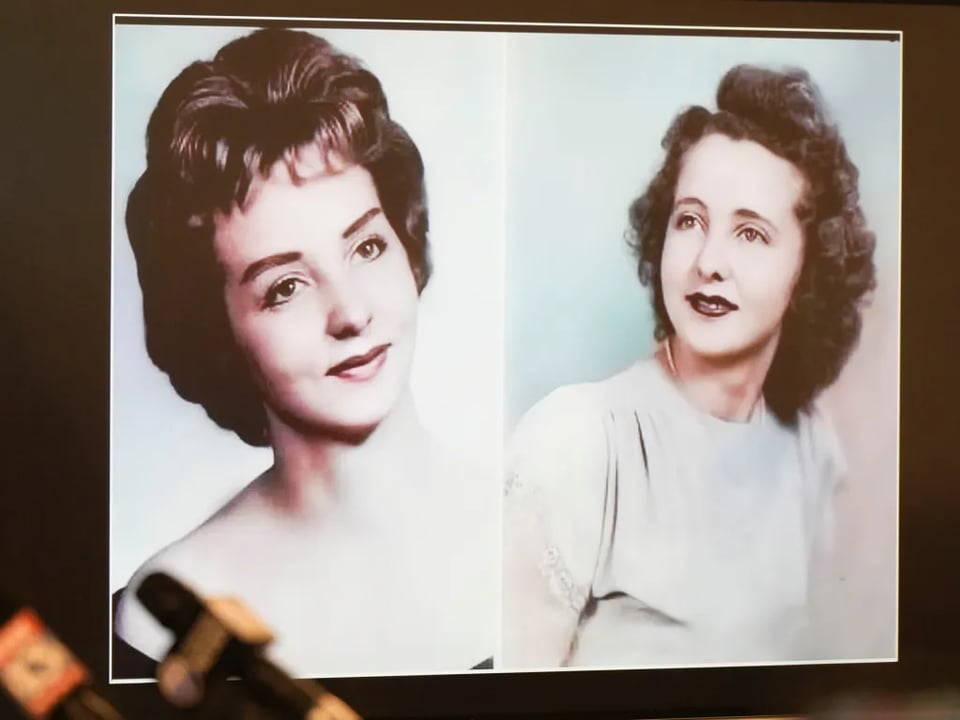

Before the year ended, my latest feature story ran online at Rolling Stone, on the legend of Buford Pusser, McNairy County sheriff and the basis for the 1973 film Walking Tall (and subsequent sequels and remakes, as well as albums), and how seemed to be upended for good when the area’s district attorney announced last August that he was, in fact, the prime suspect in the murder of his wife, Pauline.

Though other people have told this story very well since the revelations — I highly recommend Jessica Pishko’s story for Slate and the two bonus episodes on Gone South, hosted by Jed Lipinski — I had different questions to probe, namely: how did this myth get made? How soon did people know that Pusser’s exploits, and his version of what happened to Pauline, were anything but the truth? And how did this unresolved tension affect his family over the course of several decades?

For answers, I traveled to McNairy County, Tennessee, a three-hour drive from Nashville, to talk to locals, visit the Buford Pusser Museum (yes, it exists, and will stay open), consult a 2,300-page file from the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation, go on a bus tour with law enforcement, and visit a dive bar on the Mississippi state line. I learned a lot by being physically present, but I learned even more, as I expected, from the paper trail, be it investigative documents, memoirs and books, or old newspapers.

I also talked to Patterson Hood, co-founder of the Drive-By Truckers (which included three songs about Pusser in their 2004 album “The Dirty South”), who had the best reaction:

“I said all along that he was a piece of shit!” Hood says. “It was also pretty common knowledge back in those days that he was no better than the people he was fighting — and maybe even worse, because he had a badge and that made him extra powerful.”

But my favorite source was Cammy Wilson, a Corinth, Mississippi native who was working for the Dayton Daily News as a reporter in 1973 when she got assigned to look into Buford Pusser. She spent weeks in the area and the story she produced ruffled a lot of feathers — largely by puncturing the myth and painting a portrait of a dangerous figure. Pusser wasn’t happy, to say the least. Wilson, not eighty, had lived in Vietnam for two years during the war and later said that McNairy County was nearly as scary. But she always hoped the truth would emerge: “I waited over 40 years for someone to fully tell the Pusser story,” Wilson told me after the story published. I’m glad I could tell it as it really was, and not as so many others wish it to be.

Here’s to more truth and less myth in 2026. Until then, I remain,

The Crime Lady