The Crime Lady: A Few Questions for Kate Summerscale

Dear TCL Readers:

Kate Summerscale is one of my true crime touchstones. She knows how to turn real-life historical mysteries into engaging narratives, and ever since she established her reputation in the US with The Suspicions of Mr. Whicher back in 2008, Summerscale has delivered consistently excellent books like The Wicked Boy (2016) and The Haunting of Alma Fielding (2020).

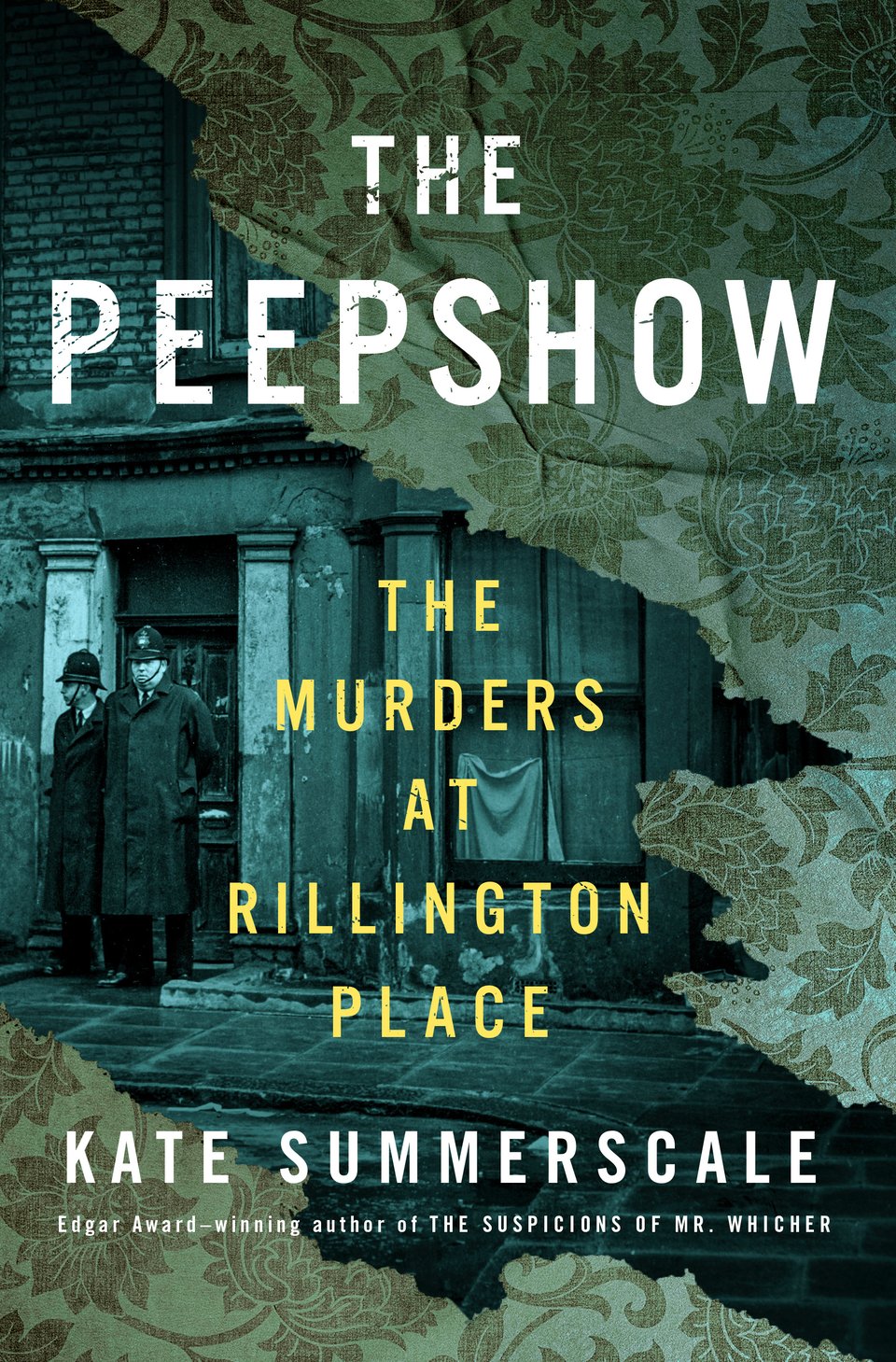

Her latest, The Peepshow, publishing in the US this week (and last fall in the UK), surprised me because it focuses on a case that crime aficionados know well — the murders at 10 Rillington Place in the late 1940s and early 1950s — but with a slightly askew perspective, chiefly through the lens of two very different writers, the tabloid journalist Harry Procter and the crime writer F. Tennyson Jesse. Their struggles and foibles feel startlingly contemporary, as is the meditation on what true crime continues to get very right and very wrong.

Oh, and Summerscale finds some documentation that suggests exactly how the Rillington place killer, Reg Christie, bore responsibility for the murders of Beryl and Geraldine Evans, for which Beryl’s husband, Tim, was hanged.

As soon as I finished The Peepshow I was full of questions for Summerscale, who answered them over email. This Q&A is edited for clarity (though British spellings are preserved) and does contain spoilers for the book, so fair warning on that.

The Crime Lady: The murders at 10 Rillington Place are not exactly unknown, and in fact have been covered quite extensively. Why did you decide to make this case the subject of your new book?

Kate Summerscale: Christie became the most notorious British serial killer of his era in 1953, when the bodies of six women were discovered in his tiny apartment in Notting Hill. His notoriety lasted for decades, not least because some suspected that he had also committed a double murder in the same house in 1949, a crime for which another man had hanged. The apparent miscarriage of justice bolstered the campaign to abolish capital punishment in England.

I turned to the case in 2021, after reading news reports of women in London who had been killed by men they did not know. I wondered why some men chose to kill women who were strangers to them, and I hoped that Reg Christie’s story might help me understand. I wanted to trace the origins of his sexual violence in his personal history, but also in the world around him, so I tried to reconstruct the case through the eyes of those who were there: the women who met Christie, the people who knew him and his victims, and the detectives, pathologists, lawyers and writers who became entangled with the case.

TCL: I appreciated that The Peepshow highlighted different perspectives, particularly a tabloid journalist and an author. Let’s first talk about Harry Procter and how he went about reporting his stories -- what set him apart from other Fleet Streeters, and what did the case ultimately do to him?

KS: Harry Procter was a working-class man from the north of England who had become a star crime reporter in Fleet Street. He was quick-witted, charming, ambitious, and ruthless in getting scoops. But in covering this case he also had a moral mission: he wanted to clear the name of Tim Evans, the young man who was put to death after the bodies of his wife and child were found at 10 Rillington Place in 1949. Harry believed that he had missed the true story of these murders when he interviewed Christie about them at the time, and he was determined to correct his error.

In 1953 he struck a secret deal with Christie, agreeing to pay for his legal defence in return for an exclusive on his story. Harry was desperate to get Christie to confess to having killed Beryl and Geraldine Evans. He became tormented by the case, and afterwards pleaded with his editors not to assign him to any more crime stories. They insisted he carry on. Harry suffered a breakdown and died young.

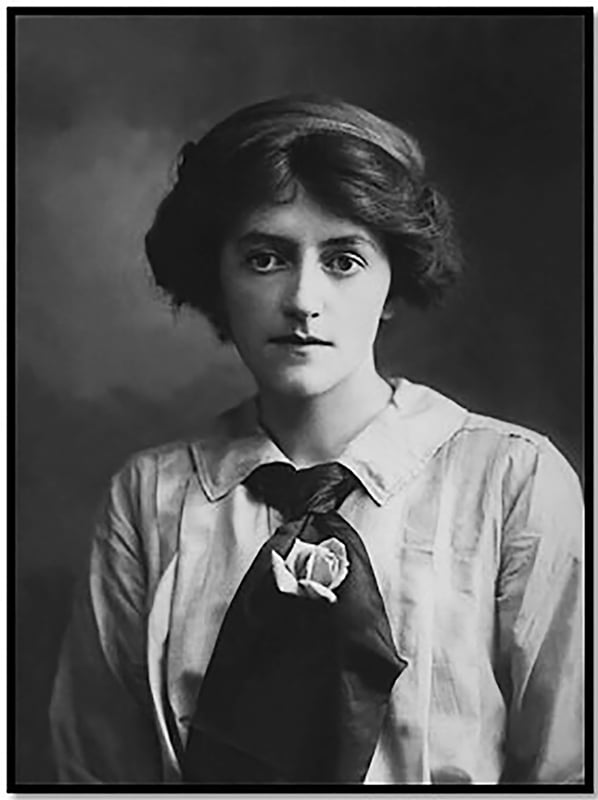

TCL: F. Tennyson Jesse is one of my favorite vintage true crime writers, and I also really enjoyed reading her novel A Pin To See the Peepshow. So I was delighted, and surprised, how prominent a character she was here. How aware of her were you before embarking upon The Peepshow?

KS: I knew of her, but hadn’t read any of her books. I started with her true crime essays and A Pin to See the Peepshow, which was inspired by a famous 1920s murder. My book’s title, The Peepshow, is an allusion to her fascination with crime, and also to Christie’s voyeurism, to the British public’s hunger to see him, and to our own appetite for crime stories.

I learnt that Fryn Jesse had led a very troubled life. By the time of the Christie case, she was 65 years old: her reputation was fading, she was going blind, and she was addicted to morphine. Gripped by the Rillington Place story, she battled to get a seat for Christie’s trial at the Old Bailey. She went on to write an influential essay about him and Tim Evans, a work of detection that was also a pioneering study of a murderer’s psyche.

TCL: Procter and Jesse seem like avatars for the way writers did true crime then, and both an example and warning for the way it’s done now. Do you see either or both of them as a cautionary tale for how to approach this genre effectively (and ethically?)

KS: They did serve as my avatars, and my companions. Following their investigations helped me to imagine myself back into their time, and to reflect on what I was doing in writing this story. I thought about their attitudes to the killer and his victims, the assumptions they made, the prejudices that leaked in to their work, the constraints on what they could say, their motives.

Harry, as a tabloid reporter, was required to sensationalise the killings, but he was also driven by a guilty conscience. He saw himself as a crusader for justice. Fryn brought a detached, chilly tone to her analysis: she was appalled by Christie and disdainful of his victims. But her arguments were sharp and nuanced, her observations astute. She said that working on the essay saved her from despair. Harry and Fryn both helped me think about the feelings that crime stories arouse and dispel.

TCL: This may get into spoiler territory, but you also found some documentation that points at a definitive way that Reg Christie, the Rillington Place killer, was connected to Tim Evans, the man hanged for the murder of his wife and child. What was it like finding this documentation, and generally, when new-to-you details emerge in the research process?

KS: I came across a document in the archives that suggested a new explanation for the killings of Beryl and Geraldine Evans: a confession that Christie made to a prison guard in July 1953. At first, I half- dismissed it as another of Christie’s lies and misdirections, but I slowly realised how this statement — made immediately after he’d been sentenced to death — might make sense of the contradictions and confusions in the story.

At such moments, the old documents can seem so fresh, as if you’re tuning in to voices that have not been heard before. In another file, I found an exchange of letters that showed how the guard’s memo had been suppressed by the British government. It was thrilling to think I had come across a hidden solution to the mystery. I had to try to make sure that I didn’t believe it just because I wanted to.

More generally, I loved scouring the huge archive for material about the women killed by Christie. There were details of their lives scattered through the files, in letters and statements by their friends, employers, landladies, families and lovers. Not much of this information found its way to the newspapers or to the courts, and it was exciting to piece it together.

The women gradually became distinct to me: the Jewish refugee from Nazi Austria who hoped to become a nurse; the sex worker who drank heavily and slept in an underground lavatory near Paddington; the Irish woman who worked in a café but dreamt of becoming an artist. The archives of a crime can give you access to details of daily life, especially among women and the working classes, that are rarely recorded in official histories.

TCL: The Peepshow is the most “contemporary” story you’ve pursued, taking readers into the 1940s and 1950s. Is this as present-day as you are going to get, or are there more recent stories that you are looking at for future projects?

KS: I prefer to write historical stories, partly because the distance makes it easier to see the connections between individuals and their society, and partly because retelling such stories is less likely to hurt people who are still alive.

Having said that, when I was researching a book about a boy who killed his mother in London in 1895, I discovered that he had grown up to rescue an abused child in Australia in the 1930s— and that this child, now a 95-year-old man, had apparently known nothing of his guardian’s crime. When I went to interview him ten years ago, in a care home in New South Wales, I had to decide what to tell him. Violent crimes can have a long afterlife.

**

I’ll be back next week with some more updates on projects, books I’m reading, and the like.

Until then, I remain,

The Crime Lady