The Crime Lady: A Few Questions For C.M. Kushins

A Q&A with Elmore Leonard’s authorized biographer

Dear TCL Readers:

There is so much to update you on — primarily print and digital galleys for Without Consent are now properly in circulation, and my month-long stint at an artists’ residency — but that will have to wait till later this week. Today’s dispatch is the latest in my ad hoc author Q&A series, and it’s on a new book published today that will grab the attention of most every crime fiction reader.

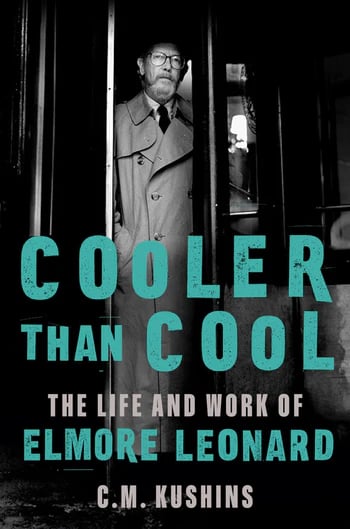

Cooler Than Cool: The Life and Work of Elmore Leonard is C.M. Kushins’ third biography and first of a writer (his earlier subjects: Warren Zevon and John Bonham.) It’s a breezy read that the Wall Street Journal’s Tom Nolan called “consistently engrossing.” It also has the blessing of Leonard’s children and mines his papers at the University of South Carolina, a comprehensive introduction to a man who kept things pretty simple: he wrote a lot, devoted himself to his family, and drank until it was no longer tenable to do so.

Leonard’s life did not have the epic highs and lows as did Patricia Highsmith, Raymond Chandler, and Dashiell Hammett, each the subject of several biographies apiece, and that is the conundrum that biographies of writers can fall into — the work is interesting, but the self-discipline required to make that work is a lot less sexy than personal chaos and self-destruction.

Which isn’t to say Leonard lived a chaos-free life. Kushins carefully documents the marriages and divorces (and the premature death of his second wife, Joan), and it is clear there was a lot of hurt to go around. (Leonard’s first wife, Beverly, was a key source, so much so that her willingness to cooperate was “a wonderful surprise”; his last wife, Christine, wanted nothing to do with the project, and at one point sued to block the archive sale, though it was later settled.) But as important as these relationships were, Leonard’s writing was the central thing, and what drew Kushins to the project.

After reading Cooler Than Cool, I had a ton of questions about Kushins’ origin story, his own working habits, and where Leonard fits in with the crime fiction canon. Our Q&A, conducted over email, was condensed and edited for clarity.

The Crime Lady: I’m going to start at the end, because in the postscript to the biography you tell a wonderful, revealing story about the correspondence you had with Elmore Leonard as a teen, and how it changed your life. It really was, to quote Richard Holmes (as you do) “a handshake across time.” I’d love to hear more about that exchange and what it meant to you, and how it planted the seed for this book.

C.M. Kushins: I’m always excited to talk about that experience, although I admit it was brief. To me, it just demonstrates the kind of person that Elmore truly was, and the patience he always displayed for younger writers who showed a genuine interest in putting in the work and learning how to write.

I have two older brothers, so I was privy to more “adult” fare when I was growing up. I was twelve when Barry Sonnenfeld’s film of Get Shorty came out and my mother went and took Elmore’s original novel out from the library for me —mainly to shut me up until the movie was released. But by the time it did, the coolest person to me had already become the little old man in Detroit who wrote all that cool dialogue for John Travolta and Danny DeVito. So, I was hooked on Elmore’s books from a pretty young age. I wrote short stories and made a feeble attempt to get one into Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine the following year, and the rapid-fire rejection slip felt something like the time my first crush told me she wanted to be “just friends.” So … I sent it to Elmore — and he responded!

It took about three weeks, but I had begged for help and guidance and, sure enough, he sent my pages back to me thoroughly proofread, along with a letter of encouragement and freshly-typed short story of his own. (That parcel was my most prized possession, and now resides in Elmore’s archive at the University of South Carolina.) I met him a year later while he was touring with the dual releases of Be Cool and The Tonto Woman, and he actually remembered me. I was beaming, and shy, but he signed both books, and what he wrote in The Tonto Woman stayed with me forever: “For Chad— Write every day, whether you feel like it or not.” So, I did.

The following year, Elmore’s wonderful correspondence got the attention of my high school English teacher, who coupled it with a letter of recommendation of his own. With those, I got my first internship at a community newspaper and then just kept writing and writing for a decade and a half. By the time my first book, Nothing’s Bad Luck: The Lives of Warren Zevon, was released, both my mother and Elmore had passed away, but I celebrated the book’s publication by dedicating it to her and then making my own trip to the University of South Carolina in order to donate my correspondence with Elmore to their incredible literary archives. I couldn’t believe that Elmore had saved my letters to him! It was a very moving and surreal experience and, after I saw the amount of exclusive material they had—all of which I knew my fellow Elmore fanatics would adore—I sent the manuscript of my second book, Beast: John Bonham and the Rise of Led Zeppelin, to Peter Leonard and asked for a blurb. He not only gave me a wonderful one to include, but that started a warm dialogue with the Leonard family that resulted in permission for me to pen Elmore’s life story just in time for what would have been his centennial birthday.

TCL: Though I am not a traditional biographer per se, I have relied heavily on archives and literary correspondence for my books. What was it like to sift through Leonard’s archive, and did having that access alter your perception of the work and of the man?

CMK: Getting to do all that with Elmore Leonard as a focus was a joy. He had also taken steps to make things a little

easier for future researchers or biographers, like saving everything, more or less, of relevance since 1951. As a lifelong fan, holding the original carbons for “Three-Ten To Yuma” and the drafts of Stick, LaBrava, and Get Shorty —all corrected in his famous blue ink — felt a secondary story was already unfolding, the words and thoughts in between the lines of exposition and dialogue that he’d put down.

I suppose I was at an advantage knowing his work so well from such a young age, but when I would notice that he’d altered character names or removed subtle lines of dialogue from famous scenes, for instance, the biographer in me couldn’t help but think, “why did he do that?” —and then begin to imagine that I’m the author making those choices. Suddenly his intentions and humor began to bubble up to the later drafts and the narrative of his inner creative life suddenly became as vivid as the fiction he was writing.

From a more playful, but equally important, angle, the idea that Elmore saved so many family photos, his old childhood homework — even his expired library cards — and, especially, years and years of detailed day planners, seemed both nostalgic and pragmatic. He saved all his personal correspondence, including fan letters, and saved anything and everything that had to do with his children and grandchildren. And, of course, he saved all of his original materials from Alcoholics Anonymous, his notes included — which was invaluable when it came time to address that topic.

The collection itself taught me so much about both the writer and the person he was: a good, hardworking life preserved in minute pieces, and an artist who refused to stop learning how to get better and better.

TCL: Cooler Than Cool certainly gets at the sheer day-to day of being a working writer, and in Leonard’s case, how that diligent work and output took years to pay off in a commercial and later, a critical way. The challenge of a life like his is that the drama - with a few notable exceptions - is mostly internal. How did you balance making sure readers knew what they needed about his work and what they needed to know about him and particularly, the good and the not-so-good about his personality?

CMK: I appreciate this question immensely. Consistently maintaining the balance you’re describing may be the only real challenge with the book — other than edit it down from its original length (another byproduct of having so much of Elmore’s wonderful materials preserved). You’re very right that in telling the life story of an author, everything is, indeed, internal. But with Elmore, it was possible to trace how his creative decisions and his personal ones all intersected each other: his stories came from the newspapers he had delivered to the driveway in Birmingham, Michigan, or from personal experiences, and his characters often began as loose variations of people he knew in real life. From that, I was able to parallel some stuff between his two worlds.

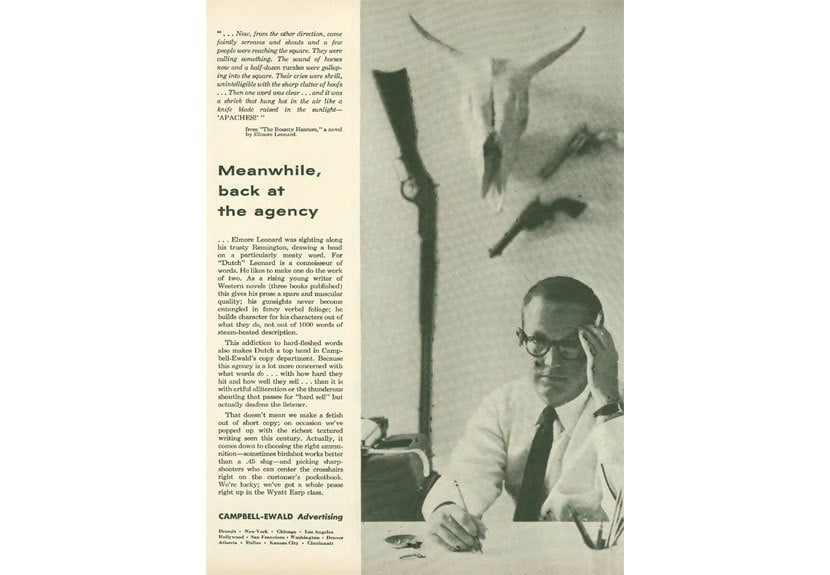

Elmore also drove himself to succeed in his two major endeavors, fiction writing and advertising. I stress that because it’s easy to forget that Elmore always had two jobs: he was active in some form of copywriting or advertising until the early 1970s, and even reminded one interviewer, “Advertising was very good to me.” He admitted that it staked his writing and, when his reputation finally allowed in the mid-1970s, he replaced his secondary “day job” with screenwriting—which was probably just was frustrating to him as the advertising work he’d left behind, although now, at least, he was independent. That certainly helped his writing—and funded it. As his biographer, his having dual work lives, as well as being a very active and “present” father during his children’s formative years, gave me three concurrent narratives in his life to keep bouncing back and forth from—kind of like one of his novels. With all that in mind, it was interesting connecting those threads and showing readers how he found inspiration everywhere—and was always amused.

TCL: I was also struck by the struggle, as portrayed, Leonard had with alcoholism, in that it took a lot longer, and more failed attempts, to first quit drinking and then eventually find a proper equilibrium. Your previous books also examined similar terrain, and I wondered if you noted any parallels or resonances between these three men, and if there is a common thread in your biographical subjects.

CMK: It wasn’t intentional but, yes, I did write three

consecutive biographies about functioning alcoholics — and all creative artists who put their struggles into the work. With Warren Zevon and John Bonham, pretty much everyone who knew them were aware of their struggles, including the media. Warren always had a support system, but he often pushed those people away and didn’t achieve sobriety until he was, more or less, ready to face it himself. When I interviewed people who had known him, it was fascinating to see that those who befriended Warren during his most chaotic years were more guarded at first, well-aware of what those addictions had done to his life and career; his post-sobriety friends, however, all claimed they couldn’t believe that the Warren they knew was the same one from all those old Rolling Stone articles—the “rock and roll werewolf” had matured into a sort of curmudgeonly, professor-type who joked that he couldn’t recall full decades of his life. John Bonham, however, was so successful at such a young age—and made so much money for so many people—that he was constantly surrounded by neophytes willing to fuel any addiction that would get him on stage, like Elvis Presley.

In Elmore’s case, none of his work associates or editors were ever aware that he’d ever had an issue with alcohol. I think he was honest about it later, when he claimed he never realized it was a real problem until marital problems escalated and a friend recommended to him AA in the late 1960s. Up until then, he had been accustomed to social circles that were all heavy-drinking atmospheres: neighborhood antics, the Navy, then the “three martini lunch” culture — although that wasn’t actually his drink. But I think he had a string of wake-up calls that he took seriously and spoke about pretty openly later on.

When I was writing about it, I made a promise to myself and his family that I would only include as much about that period as Elmore, himself, had shared throughout the years. In 1985, he wrote a pretty powerful essay entitled, “Quitting,” about how he got sober—and he would often mention the number of years he’d been sober to interviewers as he got older, or some of the lessons it had taught him about his own mortality and need for creative focus. I was good working with that.

TCL: Leonard’s later reputation vaulted him out of genre circles, but he never forgot his roots as a writer of Westerns and crime novels, and I hadn’t realized, for example, that his famous “Rules for Writing” started off as a speech at a Bouchercon. What did working on this book clarify about his relationship with genre, and the writers, past and contemporary, he was in conversation with?

CMK: With the Westerns, I think Elmore viewed that whole time period in two ways: it provided an outlet where he could develop as a commercial fiction writer, and it supplied him with a relatively dependable supplemental income that let him that education going. He also had a fantastic early agent named Marguerite Harper — a bit of an unsung hero that I hope readers will find as fascinating as I did — who discovered him and taught him how to work successfully with editors and publishers. Elmore always claimed that he wrote Westerns because he liked Western movies, but even from the beginning, Harper was telling him to push for contemporary fiction.

I think he certainly did enjoy the process of putting his research together in a creative way, but he also admitted later that there was an intimidation factor in having to write uniquely within the most mainstream genre of all—“popular fiction”—which would have required learning a while new style of writing. And just as he said about the advertising world, the Western genre “had been good” to him; he’d published over thirty short stories and five novels, two of which had been made into films. Later on, when he was really satisfied with his contemporary voice maybe 1970 through 1972—I think Elmore looked more fondly on the Western tradition because he’d learned he didn’t necessarily need it to be a writer anymore.

With his contemporary crime writing, however, I love that Elmore used Dizzy Gillespie and Marian McPartland as the jazz artists he related to as a writer. But I’d disagree, since his stance that he just wrote “what he liked” most mirrored Miles Davis, who compared listening to genres of music to pushing the vegetables to the side of plate: “Eat what you like, skip what you don’t.” He was very modest about how he worked and seemed to really dislike the over-analysis of his style, even though, intuitively, knew which rules to break for the biggest linguistic impact—something that seemed to benefit him in both fiction and advertising.

From what his archive demonstrates, Elmore shied away from talking about writing with other writers too much if it took him away from his desk for too long. Other than that, he corresponded with a lot of writers - Margaret Atwood, Raymond Carver, and Jim Harrison, to name a few — I didn’t even know he knew! And he always responded to fans seeking advice on writing, including me. What’s interesting is that, although he read a lot of contemporary fiction in his later years, no one ever seemed to affect his style or sound.

TCL: Finally, what would be one takeaway for readers new to Elmore Leonard? Should they start with the 70s Detroit novels or the 80s Florida ones?

CMK: The fun question is always the most difficult (and I hope you’ll share your answer, too)! If someone is new to Elmore Leonard, but they’ve heard of his books from a movie or television show adaptation, I think it’s safe to start there, only because I know that you’ll be hooked. Otherwise, if you read Stick, LaBrava and Glitz consecutively, you’ll probably want to read everything he ever wrote. Personally … I think Cuba Libre is a masterpiece of historical fiction, and he deserved significantly more critical attention in 2005 for The Hot Kid.

**

Many thanks to Kushins for taking the time to answer my questions. For what it’s worth, I think his answer on where to start with Elmore Leonard is the correct one, though for me, personally, it wasn’t until I read Fifty-Two Pickup and The Switch that Leonard’s writing really started to click for me (though I did enjoy The Hot Kid and said so for The Baltimore Sun back in the day.)

I also appreciate Leonard much more now, as a middle-aged person, than I did in my twenties and early thirties. Do I wish he wrote women better on balance? Absolutely. (I still prefer Jennifer Lopez and especially Carla Gugino’s versions of Karen Sisco than the written original.) But what I once took for glibness about the human condition reads now as a deep understanding of mortality’s knife edge. Sentimentality had no place in his fiction because it had no place in Leonard’s life.

Until next time, I remain,

The Crime Lady