Three Subjects: Huysmans / Araki / Religion

Like my work? Donate what you can: paypal.me/langdonhickman1

*

Huysmans

I've been reading J-K Huysmans for about the past year or so. I realized at a certain point that despite circling it in college and my interest in the Decadents, especially the effect they had on the world of poetry, I had never actually read A rebours, or Against Nature. People have some feelings about that translation of the title; it admittedly comes across more strident and almost Germanic than the definitely-French novel really calls for, but it does at least capture the thrust of the book, which is a man retreating into an increasingly monastic life surrounded by books and plastic plants and photo prints and fine furniture rather than, well, the natural world. It's position in the Decadent canon is fascinating in part because the entire ending of the book hinges upon the unlivability of that kind of life; his health declines rapidly and suspiciously and so, under doctor's advisement, he returns to the world. Me not having read it was especially strange given it is literally the book that Dorian Gray, the main character of the titular Picture of novel by Oscar Wilde, cites as his inspiration for doing all what he did with the evil and whatnot. Wilde is, for obvious reasons if you peruse his biography, a secular saint both of queerness and of literature. He represents Dionysus crucified in a lot of ways. But anyway.

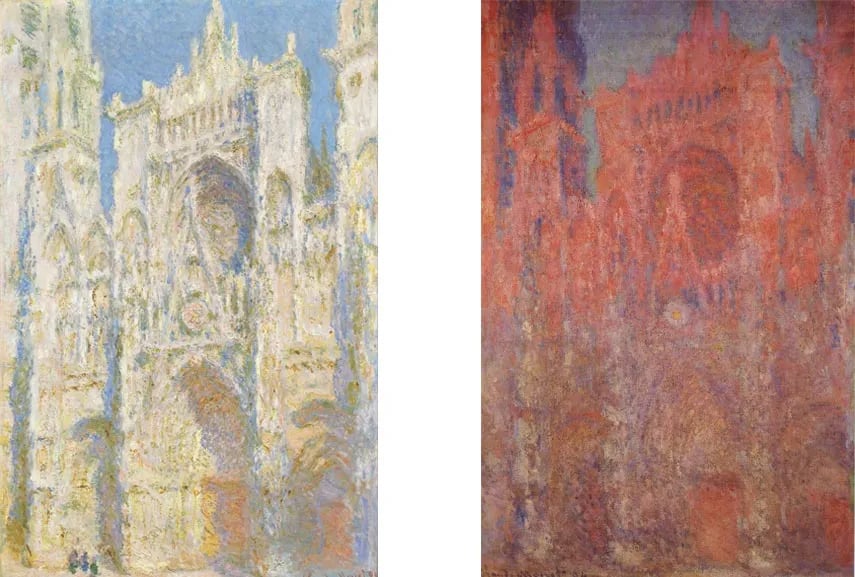

I learned from the introduction of the Penguin edition of the novel I picked up I believe from a library sale but maybe just the bookstore that A rebours was followed by four novels, all hybrids of fiction and autobiography starring the stand-in character of Durtal, mirror to Huysmans. Fascinatingly, these books chart Huysmans bottoming out in the secular and quite voraciously godless world of the Decadents, themselves quite taken with the rising and increasingly imperious scientism of the late 1800s, only to find himself semi-spontaneously converting to Catholicism. The first novel, La bas or Down Below, concerns Durtal writing a biography of Gilles de Rais, the famed killer of children and presumed Satanist, and for whom the character attends a black mass for research. The next novel, En Route, concerns the character's conversion for no clear reason (though, given the previous book, it's not hard to piece together) and eventual trip to a monastery for a week or so of life there in order to strengthen his faith. The next, The Cathedral, is the one I'm reading now; the character journeys with the Abbe of the previous book to the new church he will serve and contemplates writing a biography of Venerable Jeanne Chezard de Matel, founder of the Order of the Incarnate Word. In the last novel of his life, The Oblate, the character lives as an oblate, or layman who nonetheless lives by monastic rules.

I wanted to read this sequence because the emergent natural structuralism of it caught me immediately. There is a movement from one extreme to the other, with the center novel being precisely one of the moment of inversion. It also charts a really catching shift in a person's mindset. The main character of A rebours, as parodically intense as he's presented, was based in part on Huysmans himself, an autocritical means of looking at the influence people like Emile Zola were having on his life. By the end, Huysmans was writing about his own very real experience of being an oblate for a period, one of the more extreme means a layperson can take their faith, akin to retreating to a Buddhist temple for several months. I'm not religious, as I've written before, but certain stains of the life don't clean easy from the soul, and regardless one's faith is an intensely personal and inward thing often resistant to reason and rationality. I've written a good bit about ineffable grace and its necessity; other religions differ on these points obviously, but the draw within Christianity of a god of infinite mercy seems immediate and intuitive, where a sober-minded adulthood brings to bear on the mind a number of unresolved sins and grievances which weigh down anyone with an iota of a functioning conscience. In order to not collapse fatally under that weight or descend into ultimate suicidal despair, we invented a light at the bottom of the ocean, a sliver of light that can nourish you even in bleak pits. Viewing religion as invented by man makes this more beautiful to me, not less; the intensity of our grieving and dolorous desire to be loved and protected and just given a chance despite how ugly and wretched and without hope we can feel gave birth to an entire religion, as well as aspects of several other faiths. Even the violence done by faith and the churches of the world gets transformed when thinking of it in this way, an ugly tragedy where the desire for deliverance and the safety of our soul, a thing we feel even if it's not strictly real, allowed or at times encouraged the exact violence it seeks to deliver us from, completing its own myth of the original sin and the sin-nature of all humanity, thus indeed the necessity of a savior. It's bleak but poetic.

As a writer too I was fascinated by Huysmans resolute refusal to have events occur. A rebours is a man describing rooms he is in with intense detail while absolutely nothing happens inside of them. The black mass Durtal visits in La bas comes only very near the end and is present for a single chapter; otherwise, it is him talking to his friends, writing letters to a lady, and a brief sex scene. En Route can be split in two, the first half where he is in a church obsessing painfully about his newfound faith and his temptation to go back and fuck the Satanist and the second half where he prays inside of and walks around the monastery. The Cathedral, which I'm only 100 pages into so far, promises to be mostly him thinking about a pastoral town and its church. While I haven't read The Oblate, it is hard to imagine that it contains much of anything in terms of eventness.

As a writer, this is one of my soft spots. It feels often to me like writers use eventness and plotness to cover up a paucity of character. People like to trot out this line that novels are characters make choices and the ramifications of those choices, but this to me strictly focuses on only one aspect of life, which is the direct agency we have on our own existences. Even something as simple as feeling helpless in the face of controlling forces of politics and economics suddenly can't be talked about in that form, but Kafka and Pynchon existing tells us you not only can but you can do so and be one of the best. Likewise, there is a tired truism about poetry that it is about moments and where strict narrativisation is frowned upon. Again, this falls apart pretty quickly if you survey the world of published poetry. There can be novels about stillness, which takes up so much of our life, those moments of sitting in a parking lot before you had a cell phone, waiting for something without a way to tell the time, pacing around and kicking rocks under cars and watching people in the distance mill about. Likewise, there is poetry about motion, the arc of history, the flesh of the world.

There are times in life where absolutely nothing is happening or going anywhere but you feel so fucking much. That's not a particularly literary sentence but it's not meant to be; speaking plainly, there is a common poetry in dumb experience, as in mute or without words. If anything, prose that hinges itself on actions and their results feels at a certain point safe and easy. You can built out a story from just an event without setting or character; it begins to ask to occur somewhere, to someone, or be witnessed by someone, be responded to, on and on, and so a narrative kind of naturally emerges from the ether as you tug at the semi-transparents structure. Working within protracted stillness is different. You have to really stretch your use of language. It's not just about large words or just about small words, not just about short concrete sentences or long mossy winding overgrown ones. You are a catalog, an index, a painter, given a still life and asked to make it feel like something. In short, you have to act how a poet would but within the expanse of prose and, for a novel, do so for a long fucking time without it feeling utterly lifeless or pointless. This is a very exciting challenge to me, especially as someone who's spent a decent amount of my life in hospital waiting rooms, lobbies, the passenger seat or back seats of cars, on couches waiting for people to get off of work, in bed as night ticks past while no one else is awake, staring out onto blank fields. Literature for many people has always been a way to reclaim a life and declaim its value to the world, even if it is a negative value.

I plan to write more extensively about the five books once I finish them but already I've seen some interesting structural events occur. For instance, in that span of five novels, the character at the center is writing a biography in the second and fourth, the same positions against comparative median of the third novel. In the former, it is a deeply Satanic figure, the wicked Gilles de Rais; in the fourth, it is a Venerable, a respected church figure two or so steps down from sainthood. Likewise, the first, third and fifth novels form peaks of monasticism, from the worldly cloister of the rich man's well-decorated home in A rebours to the substantially more spare but no less isolated spiritual man's cloister in The Oblate. The third, En Route, breaks this pattern of monasticism but only slightly: it is about his ascent to a monastic life, one not yet achieved. This means that it is only in the spaces between monasticism that we see the central figure writing biographies, exploring lives that are not his own. That these pursuits and monastic isolation do not ever coincide with each other and seesaw back and forth is a fascinating one especially to have inadvertently nurtured over the course of a career in letters for roughly a decade.

We also see a fascinating component of the reversibility of the order of the texts. Certain elements would need to be slightly reconfigured, but if you start as an oblate and then move to life about a cathedral, taking another stab at spiritual life that leads you back to Paris where you meet a woman, a woman who takes you to a black mass and shakes you of faithfulness until you shut yourself up in your room surrounded by books and plants to get away from the world, this too is a coherent arc. In some sense, obviously, any historical arc can be reversed and so on the surface this isn't much of an observation, but the bidirectionality here survives in a way other types of progressions of life or history do not. We can't really imagine un-inventing copper or the atom bomb or the automobile, nor can people start divorced before getting married and then unmarrying to merely dating as they grow younger. An emperor cannot spring to life from the dead by having the knife slide backwards out of them. A bidirectionality of narrative obviously isn't impossible and this isn't the only bidirectional historical arc in literature, but it's fascinating to find one that still feels coherent as the progression of a character based on their experiences in the world and not merely events read backwards.

It's fascinating as well what elements stay the same across this span. We see Huysmans inserting himself as a character drawn always to monasticism as the peak of life, that he must abandon the world entirely whether it is to pure atheistic aestheticism or to the lord. In fact, it's fascinating even more so if we read A rebours as parodic of that kind of figure emergent in Decadent writing, that what he once jeered as silly and over-committed to the bit becomes exactly who he would be later in his life. Likewise, the resolute attentiveness to indexing and cataloging all of his surroundings and his understanding of their aesthetic history in painstaking detail never once leaves him; whether in faithless drugged stupor or in fidelitous spirituality, he remains precisely the same, focused substantially more on the image and affect of the materiality of the world than of its people, per se. This in turn makes those two biographies much more fascinating; they read suddenly as a man striving to understand life as something shared and occurrent within people and not just something outside of himself, to make contact with something he doesn't seem to naturally feel.

My thoughts on all of this will get richer, obviously, when I finished The Cathedral and then The Oblate but I'm already excited by what I've found. It reminds me of another long-form reading project I'm in the midst of that has yielded similar results albeit from a very different source.

Araki

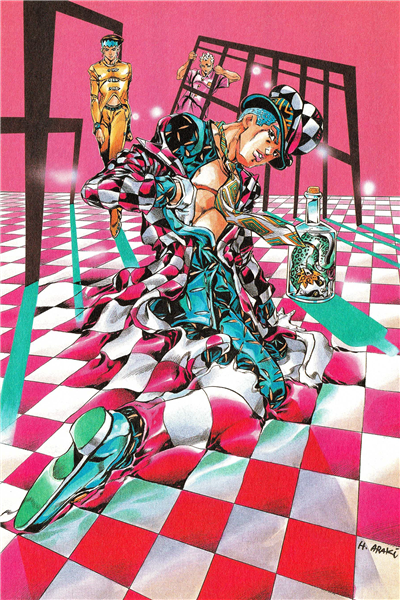

I'd heard of JoJo's Bizarre Adventure obviously, given I've been surrounded by weebs my entire life (plus I jocked heavy with that Dreamcast fighting came based on it), but I'd never sat down to read it, let alone watch it. It just sort of sat in my periphery, hovering due to the shared interest of friends but moving it felt slowly away from me as my interest in comics shifted direction and I began digging more and more into literary and avant-garde fiction. Eventually though, maybe about a decade ago, I caught some episodes of the anime adaptation of Part Two and later Part Four over the shoulder of my roommates and was obviously impressed with David Productions work and what it implied about the quality of the source material. In truth, the inventiveness of the material never was what turned me off of it. Instead, it was the perniciously weeby way a lot of anime fans would talk about it, with catch phrases like "Araki forgets" referring to what they saw as plot holes or gaps in logic, or gestures to how cool and crazy the battles were, something that has become less immediately interesting to me the older I get. I sat and watched a chunk more of the material, finally picking up on the truly obscene amount of music references seemingly tailored specifically to someone like me, what with the constancy of progressive rock and 80s hard rock that has since fallen largely out of favor. Eventually, between how frankly fucking cool what I was seeing was, the liminal literary elements I could see burbling beneath the surface with its particular almost post-Dada hypnagogic dream logic plus my adamant and never-disproven thought that weebs are functionally illiterate, I set out to read the source material, convinced deep in my soul they missed something that would be obvious to me on picking it up.

(When I want to be condescending, I can be condescending.)

I was told to start with Part Four or perhaps even Part Three, because that's when it "gets good". This was, to me, yet another tip off that I was being advised by illiterates. Add on top of this my deep and long-set interest in watching a work or artist develop over time, to see what minor elements that perhaps go unmarked early on recur later, transform, cross against one another, and the idea of starting anywhere but Part One (you know, the start) was anathema to me. Thankfully, Viz had recently, due to the success of the anime or maybe the other way around, picked up the rights to the recent hardback JoJonium editions that had come out in Japan and were steadily releasing them in English, so I had before me not just well-translated versions but also ones with good paper, good ink, good binding, etc. Realheads of the reading world will understand.

Without belaboring you too much with several years of releases spread out over six parts totalling something like 45 volumes, five spin off volumes over two series and one non-fiction book about drafting shonen manga by Araki, I wound up having precisely the kind of edifying time I expected. For instance, Dio, the main villain of the series who bears a striking resemblance in many ways to the character of A rebours (a fact I absolutely neither knew nor expected), appears as a primary force primarily in odd-numbered volumes, being the clear villain in parts 1 and 3 and his progeny being the main character of part 5. Meanwhile, even-numbered volumes featured one-off primary antagonists which served primarily to fill in an understanding of the world per Araki's vision. Part 5 again becomes curious here, and 6 as well, because part 5 features a one-off antagonist but with Dio's role given to the protagonist, while part 6 features the shadow and influence of Dio as an explicit and quite major component despite never personally appearing. These kinds of structural elements of the work, the bones upon which the flesh of story is hung, was never mentioned to me before. I'm certain some people picked up on it; I don't believe I'm the first to see it. But to walk in without any of that fascinating sense of structure mentioned at all just felt silly.

Likewise, the logic of the work immediately betrayed to me that it was not, in fact, semi random bullshit. His work is driven by an aesthetic logic, one of visual symbolic development over strict narrative. That said, the fundamental underpinning of the arc spanning those first six parts is a generational gothic horror, the progression of a curse over time, and, as any great visual artist will find themselves drawn to, a tale of alchemy. That Dio, ever the vampire, is pitted against a family whose powers always seem to revolve around life, from the growing of vines to the restoration of broken objects to the bringing to life of non-living matter to the unspooling of DNA to even the raw perennial potentiality of life itself, is openly alchemical in its conceit, as in driven almost explicitly by The Chemical Wedding, the quintessential Rosecrucian text of alchemy. This is paired against the symbology of the Tarot in the third part, including its progression as mapped out by Crowley. These things can be read as occult, sure, but even when they were spiritually infused by occult practice, they were first and foremost a way of encoding meaning in visual iconography that can then be manipulated by visual means. It's not hard to find writing by Araki where he describes his intense thought process regarding the designs of characters and all the fine details dotting their clothing; it's not a hard leap to take from there that the wielding of powers against each other forms something closer to a visual dialectic, an alchemy, rather than being driven by common banal logics.

For instance, something I noticed was that the main character always seemed to have power related to circles or spheres, and that this shape was associated with perfection and goodness. Likewise, we have a curious symbolic motif that recurs across several parts where a reptile of some sort is imperiled only to be aided by the main character for no particular reason and no gain. The only time this is violated is in part 6, where Jolene instead antagonizes an alligator by throwing a rock at it from a moving car again for no clear reason; this is also the only time that the main characters "lose", at least in a certain view, with the world taking at least one if not more resets before the conditions that lead to the defeat of Pucci are achieved. I plan at some point to sit down and do a more thorough close-read to catalog this stuff and map it out, but those are little bits I can recall off the top of my head regarding structuralisms that I just genuinely didn't see much of anyone talking about regarding the work.

I mention this all because those sublimate structures are honestly some of my favorite parts of art in general. We naturally generate structure to forms; without boring you with tedious neuroscience and metaphysics, we tend to want not just to understand an object but to have a system with which we might anticipate future objects and have some form of understanding to them. Obviously, the nature of the world challenges this sentiment, but that's also what the process of expanding awareness and learning is; it's as much about updating our systems of knowledge, rubrics of understanding, as it is about the specific thing we are trying to understand. That in art these structures hang against the more immediate aestheticism, the line level or specific image or frame of the film or tone of the instrument, is a perennially fruitful dialog. Once you learn to think toward those things, it's hard to stop.

Religion

What draws me toward the nearly Ur-Catholic works of latter day Huysmans isn't just the narrative form of intense stillness nor the shocking (at least seemingly) reversal of a mind and life or of the emergent structures that come from it. Any who follows my work knows I have a long and deep fascination with the divine. Theology was more practically my inroads into philosophy, which in turn became my road out of spiritual faith. But while there is a surge of people who are "spiritual but not religious", I often find myself somewhat counter, or inverted: religious but not spiritual. I am not, admittedly, beholden to one religion, but I think especially when you strip them of the theological substrate of absolute truth you can begin to see them as what they are, which are complex nests of interwoven threads of philosophy all sharing a common note which is our human situation among the eternal. The eternal in this case doesn't need to be divine; it can be the immensity and scale of time and the universe's scale, the intense vertigo when we think of those infinite gulfs before life and after death, or even just our interrelation to a large and complex world that certainly values more than just us. Once you learn to get over your own religious trauma to see past the symbols, you can begin to see the symbology; religions and faiths unfurl themselves into nets in the mathematical sense, nodes of thought with connective edges making system-graphs within which you can find either parallel geometries or Hamiltonian paths but also note the interest specific and semi-unique shapes that come up.

I am not shy either about my struggles with apeirophobia, though I don't always use that particularly granular word for it. I don't just think about my place within the eternal; it becomes this intense vertigo-inducing overwhelm for me where I think about everything. Breaking this pencil means it will not longer exist ever again; throwing a toy in the garbage removes from the lattice of conjoined histories every history involving this touching lives, whether they be human children or grass and weeds in a field or animals looking at it with puzzled expressions from afar. It's hard for me not to see any given action as choosing one and foreclosing an infinity, which produces the dual affect of amor fati in me, the wild embrace of fate, but largely because that's the only way I can seem to act at all through that paralysis. I do a lot of things that embarrass myself, but it's either that or freeze up and approach that same stillness.

So texts of the deeply, wildly faithful struggling within their faith often move me not because of the specific spiritual matter, of which I am more or less ambivalent toward, but because of the kinds off architectures of being people enraptured in that way pull out of life. I don't think it's fair to say that these struggles are deep in the sense of better than another kind of struggle; they are deeper, certainly, but the same way an aquifer is deeper than the grass, but paranoia about the state of an aquifer can sometimes lead to you destroying the land to chase something that may actually have been fine all along, to follow that metaphor to it's end. Granted, sometimes you do find a problem. I don't think comparatives within that world, which of the problem-vectors of life and being enraptured us with paranoia and passion, make much sense at all. If anything, the diffuse and decentralized network inherent in living systems and ecosystems writ large means we can specialize without worrying really that something is going unattended. You need bricklayers and farmers to have a world, but if your world only has bricklayers and farmers, they have done a very bad job building something enduring. (We do not have that problem; the proletariat is nothing if not capable of enduring feats.)

Granted I see people like me online, who I'm not going to name but you could find on Twitter pretty quick if you poke around, who seem to take this and undergo frankly a puerile religious psychosis. It's one thing, I think, if someone devout in a faith through life falls into one of those fits; the root ordering systems we use to make the semiotic relationship between us and the world understandable going haywire and burning our minds is literally one of the oldest stories in the book, the fundamental epiphany of every madman or saint in history depending on the quality of the breakdown. It's another though if someone emerges from a faithlessness and undergoes those open and radical stretches of religious psychosis. You are watching a mind melt like a candle. This isn't the same, to be clear, as someone simply finding faith over time. One's faith is fluid, like water, and changes to fit the shape of a life; I've become more fond of Islam over time, especially with how syncretic it is to Buddhism, specifically in the interpretation of Allah as the lord of all, not just the lord of goodness and peace but of every possible and actual thing in the world. This more comprehensive view of lordliness makes more fundamental philosophical sense and, using images of god as semiotic ordering mechanics for thinking about other things a bit more concretely and less overwhelmingly, it works substantially better than bizarre irreal dualism. (Can't me not being a non-dualist; you can't.) But you can watch some people tug at philosophical strings, whether they are loose in the field or just loose in their minds due to naivety and lack of reading in the field, and then watch them utterly dissemble. It's embarrassing.

This is, in a nutshell, the sorcerer's dilemma, a thing I've found myself talking and writing about a lot. The underpinning aspect of cosmic horror is a kind of cosmic pessimism, that the world, the universe, its systems, its totality, its potentialities and its actualities are beyond the scale of human comprehension. This can sound flippant, but it's also maybe simpler to say that it extends beyond what any given mind could comprehend and for a few simple purely mechanical reasons. First, the Planck length exists not so much as a fundamental limit to space but a limit to measurement of space; any energy used to ping a space smaller than that would be sufficiently large to fuck it up, meaning we can't reliably see anything beyond that scale. Continuities and waveforms (ignoring the perplexing dual-state of wave-particles) tells us we should expect an infinitely extendable domain, that we can zoom in more and more forever and not reach an end. But we can't. It doesn't mean what is there is necessarily mind-blowing, but it does mean we can't look at it, not really. We extend this in other directions; we are incapable of measuring what may have generated the Big Bang due to fundamental laws of time and causality emerging because of the Big Bang; if there is some dimensionality beyond us with which to pop out and look at things differently, we can't access it and do not have a sensorium equipped to experience it nor a mind evolved to process its information. This made scientists in the mid to late 20th century so paranoid we did a bunch of tests to see if there are hidden dimensions hiding in plain sight effecting physics. (There don't seem to be, but definitionally we might always just be looking for them wrong. Who knows.) We can extend this further and further in other domains, but that gives a pretty good snapshot; cognition, ultimately, is limited by our sensorium (our means of taking in data about the world, like heat, texture, color) and our minds (that complex meta-object emergent from our brain and connected bodily systems which crunch all that data, synthesize it in lots of different simultaneous and concurrent ways, which then gets filtered for distribution to our conscious mind). Cosmic pessimism simply says it's probably pretty likely our limits there mean we are missing something. It's probably not a tentacle monster, but those serve as a pretty good visual metaphor for "weird shit we would not expect".

But moreso, when we encounter these weirding vehicles, which in a very Freudian sense challenge our fundamental assumptions about the operation of the world much like the doppelganger he pinched from the German novel Siebenkas, they make us panic. Suddenly, when one fundamental assumption is disproven, we realize maybe everything is wrong. It likely isn't, but it suddenly could be, and the possibility of our entire body of perception since birth, or perhaps all of humanity's perceptions and cognitions since we began, all being wrong is a heavy thing to reckon with if you aren't ready. The sorcerer's dilemma is that conflict between the desire for expand knowledge found at a certain strata, using that language instead of depth to avoid ascribing a value to it positive or negative, but not only genuinely not being ready for what it might do to us when we learn it but sometimes not even being able to be ready. This is what every story about the over-eager mage who finds themselves destroyed by their own ambition, from Faust to Frankenstein to Odin in the tales of Ragnarok and on, is premised on. We made those big mythic images of it because it happens all around us. Hell, it happens when deradicalizing a red pilled friend or family member; you can see the moment they realize what they had built as their base perception to understand the political shape of the world is fundamentally wrong in an irresolvable way. It's crushing and disorienting. Hell, most people experience it when becoming socialists and further as well, that moment of reckoning with the liberal order of the world you were presented versus the sudden awareness of its current and historical atrocities.

I don't do lessons in essays like these, because that's condescending and arrogant, and I similarly don't like theses. Good work, I think, is thinking out loud as best you can and people in return thinking back toward you, or each other, or themselves, or just thinking you're a dummy who needs to work some thoughts out but shouldn't be engaged with. As for an ending? If there wound up not being a theory of everything in the sciences, whether that is one we could map and comprehend as people or not, the result would be so shocking and bizarre we wouldn't know what to do with ourselves. Similarly, religions are systems of networked thoughts; once you have a bone-deep sense that there are no angels or gods, you can see them as encoded means of generating bodies of texts to be iterated on over generations rather than purely real theological supposition. This is helpful. It opens up much more of the world, its history, and the inner lives of its people.

*

Like my work? Donate what you can: paypal.me/langdonhickman1