The Superman

1

I think often about the strange and strangulate emergence of Superman as a character into the form he has now. I saw the film recently with my good friend Gabe, who is like a younger brother to me. We have made a habit of seeing the DC movies as they come out, that being one of the things that quickly bonded us to each other, the other being communism. I met him at the coffee roastery that I worked at and briefly managed; his sister, one of six in his very large Irish-Dominican Catholic family, was working there at the time and described her sole brother as a depressed and useless lazy layabout with no drive to better himself as she handed us his application that she had filled in. It turned out this was missing a few key details, such as how his diagnosis and suffering of thyroid cancer both derailed his college plans shortly after high school and squandered all the money he could have used to return, leaving him adrift and bereft of elements of his voice after the surgery, a particularly deep thorn given his dream had been to pursue a career in radio broadcasting. It was on his first day that by chance our other coworker on that day happened to mention USSR famines, which caused both me and Gabe to twirl about like dancers to shout at him about Nazi propaganda, thereupon realizing we both were communists, a fact his sister had not seen fit to mention. We became fast friends after. He had long been into manga but had struggled to seriously get into western comics, finding he preferred DC's more mythic and abstracted approach compared to Marvel's more often grounded and science fictional approach, a sentiment I likewise shared. And so began the great data dump from my head to his, regarding comics, novels, film, heavy metal, progressive rock, and all sorts of other topics, like a big brother to a previously-estranged younger sibling.

Superman, James Gunn's film, fared significantly better for us than The Flash, the last DC film we saw together, a film so bad it caused us to skip Blue Beetle entirely despite both quite liking that character and being excited that they went with the Jaime Reyes version of the character rather than the more obvious Ted Kord. The issues with The Flash are plentiful and so deep they often fill my mind; previous attempts at this same essay saw my thoughts on the film expand and contract erratically during drafting until I decided I needed a totally different structure. In short, in the trifecta of baffling and god awful DC films, Man of Steel made me the absolute angriest, Batman v Superman was delirious and delightful, and The Flash was such a clusterfuck it felt somewhat like laughing at a cancer patient in hospice care with their family gathered around. We, like most people, have grown deeply fatigued with superhero cinema, despite both still being very big comic fans, and so we entered Superman more with a weary sense of duty than excitement. Thankfully, this cynicism was proven unwarranted; it wasn't a great film in the way the peaks of cinema are, but it was refreshingly unashamed of the character of Superman both in terms of his interior qualities and his external actions and made no move to apologize or tone down the character. It feels strange sometimes to laud a work for adapting a character or story and not also acting like they are ashamed of the source material, something you'd think would be a prerequisite for spending that much fucking money and time on something, but I'm neither a capitalist pig nor a coke-addled film executive listed in Epstein's book, so what do I know? James Gunn did good by Superman, good enough that as I was sitting in the seat, I began to ruminate on the character again.

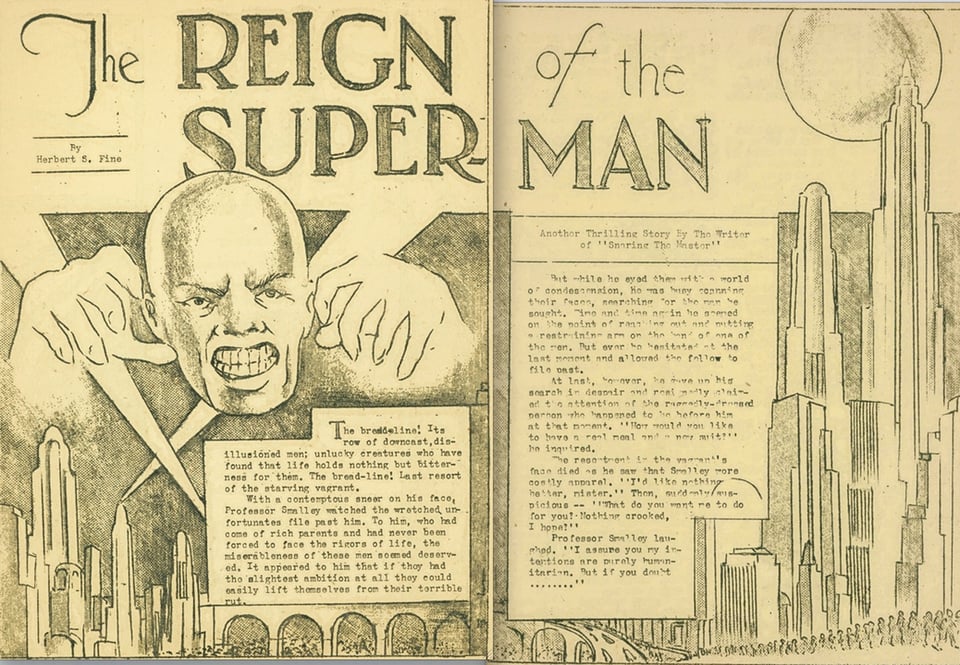

The origin of Superman is a particularly strange one. The Superman was initially debuted in a short prose piece by Jerry Siegel titled "The Reign of the Superman", illustrated by his friend Joe Schuster in a two-page story. The drawing was simple and evocative and, for later Superman fans, especially curious; a bald and scowling man, the Superman himself, hands raised nefariously over the city his target. This image is obviously shocking because, well, that's Lex Luthor, not Superman. The text of the story leans even further into this muddled characterization (or, at least, muddled to us in retrospect); the main character, a vagrant named Bill Dunn, is given a potion of super intelligence by a mad scientist which causes him in turn to develop incredible psychic powers. He sets about using these to take over the city with plans of the world, disposing of the scientist when he attempts to thwart Dunn, only to realize too late that the potion was wearing off and the only man who knew how to make it was now dead. These elements within the story largely feel like what would later come to define Luthor himself, from being a mad scientist (as in his earliest incarnation), bald, attempting to use his incredible genius for evil, and being, well, a superman.

Siegel and Schuster would later confide they were unaware of the Nietzschean angle when making the Superman, at least directly. The term had entered into public consciousness in the late 1800s and early 1900s, aided in part by Nietzsche's sister's notoriously edited versions of his works, particular the false work The Will to Power made up of lingering fragments of his work rearranged and often split between inserted fragments, constructing a false-work espousing a direct racialized fascism that Nietzsche himself was, to be blunt, too politically incoherent to endorse himself. Chewing over this question of the emergence of a superman, which we shall return to later, caused a lot of differing social discussion, including George Bernard Shaw's work Man and Superman, one of his great plays, which analyzed the potentialities of this question in his typical socialist methods albeit filtered through a largely social realistic framework (sans, of course, the third act, which is a philosophical debate staged within Hell). Culture had not yet decided on the merits of the notion of a superman or even what that type of thing might be. While the notion was argued in philosophical and political spaces in the very early 1900s, alternating between a Stirnerian individualist sense of eruptive self-becoming, a Schopenhauerian tragical self, a proto-existentialist inspiration and mocking figure to the modernists embodying both the ability to transcend generational systemic evils while also exemplifying them in the Great Man theories that led in part to World War I, and the proto-fascistic notion of a social Darwinian push toward not just producing strength but genocidally eliminating weakness as it was viewed. These questions, you might have noticed, are ones we still struggle with. Is the socialist project incompatible with self-becoming? Is it recoded liberalism to engage in self-care or is this a nourishing of the necessary vehicle of all willed political action? What is strength and what is weakness? Somehow these often metaphysical abstractions become the kernels which generate the intensities of political vectors, thought, actions. As it is now, so it was then, with these thoughts even trickling through the pulp adventure stories slowly positing their often eponymous lead characters as supermen, which in turn inspired the early caped and masked heroes of the 1930s we now see as the origin of the superhero.

Siegel clearly saw, at least in that early prose piece, the alien evil limits of this thought. Dunn seks to dominate the world based on his own notion of self-superiority, one buffeted by notions like intelligence, will and power. It is not merely these notions, however, but also how he defines them. Intelligence is a raw capacity, something one had or does not have. It is not process-driven; in certain language, it is an arithmetic object, not an algebraic or calculitic object. Those other forms of mathematical identity are engaged in the question of the generative function or process, the entirety of the range of values of a line or emergent geometry. Arithmetic thought is obsessed instead with monostatic essentialism; an Object exists or does not, with little additional information considered save at times for intensity, which is portrayed as transformative but rarely deeply considered as such. As Dunn's intelligence grew, he suddenly developed psychic powers, a clear eruptive transformation emergent from the increased intensity of his intelligence. However, this act is not viewed by him or the scientist as a threshold of transformation as much as something retroactively justified by the intelligence itself. Power does not emerge from processes but simply is or is not, and thus Dunn's possessing of it meant he already always possessed it and as such could not misuse it. It is then his will, this steely and malevolent engine of action, that becomes the final driving element of his deeds. Will to him is self-justifying; as one wills, so too do acts emerge. In a certain quite literal sense, this is undeniably true; the physics of the world do not punish or prohibit a deed based on its intentions or results but merely accepts and allows them based on both will and brute capability. This fundamental amorality of being and action is a problem that often, to be frank, people refuse to consider, instead seeking to encode morality or ethics into the fundamental metaphysics and indeed even raw physics of the world, despite the horrors of history and the present being indicative that this simply, tragically, is not so.

It's worth noting that in the story itself, this outlook is shown as farcically tragic and short-sighted. The overly venal and preening Dunn sees his power slip away from his grasp; fittingly, it is a power that can only come from another person, the one who makes the potion, and so the self-obsessive tendency of Dunn-toward-power is in fact precisely what alienates himself from power. If power be an object, then yes, he possessed it, but if power be a process, he broke it. We could argue that this doesn't strongly challenge the views of inherency given that the scientist who makes the potion is shown himself to be smart in that way, but it's worth noting that he does not administer the potion on himself. There is a communalist aspect to his sharing of the potion, even if it was short-sighted and led to his death. But more importantly, in the hands of the one receiving that power, the one who should be most aware of the communalist nature even of a potential superman, that these eruptive leaps are communal efforts, this notion is so far out of sight that he kills the scientist when provoked with no second thought at all. Both of these figures seem to outline Lex Luthor as we would come to know him, imbued with this tragical sense of the superman or the man beyond man, without denying it to be true of him.

Interestingly, however, is the lingering undiscussed trait of Dunn: that of being a vagrant. His homelessness and humility is the one lingering element that we would see later be incorporated in the Superman we know, Kal-El, Clark Kent. There is a maudlin aspect to this homelessness. In Kal-El's case, it is home being stolen from him by calamity, leaving a haunting image of a home he never knew overlaid on each instance of home he might find. Writers' usage of this potentiality varies; some choose to ground him within his adoptive parents in Smallville, others have him attain the typical adult homelessness where we move where needed for life but rarely feel permanently at home in any given location, while others linger on the haunt of that old home. We can see this in part on how often then invoke the eponym "the Last Son of Krypton", a title that hinges its impact on the sense of burdensome legacy acquired through chance and fate rather than will and deed. Regardless of the tilt writers take, however, that sense of homelessness is mirrored in Dunn for the same effect; a tabula rasa, washing away the origins so to speak of the character so that they are defined by their deeds and selfhood rather than circumstance.

This last element is necessary or any rigorous investigation of egoism. One of the primary faults of it as a philosophy, at least severed from contextualizing grounds, is how it requires in its bootstraps mentality a kind of acausality that is not granted to us in the world really ever at all. Everything that emerges into being does so within a contextualizing framework; this same problem is one that has vexed philosophy since we were able to enunciate the notion of being-in-world, that we have no tools with which to abstract something from worldness and all that contains, from history to materiality to causal relation to even relation to laws of physics and chemistry. As such, every will is attenuated. Some element is inherent, in that the contexts of our creation, upbringing, etc. contribute elements that we don't control, while some are within our active control, even if their relation to the final component of will is not always immediately apparent. For instance, who in adulthood looks back on youth and can rightly expect why this schoolyard conflict or that exchange of headphones at the back of the bus so radically dictated the shape of future life? It is not every small action that impacts us that greatly, but some certainly do, and what differentiates them from any of the other million little acts we encounter is cryptic at best. This high-sensitivity set of social, historical and psychological variables is heavenly rich soil for novelists and a nightmare for historians. To test in a pure sense the suppositions of egoism, we would need a cognizant and active will severed from causality, bursting into being uninflected so we might measure the supremacy of its might without either preexisting limits or assistance via the circumstances of birth. This simply is never afforded to us.

This doesn't mean that the notion is utterly without value, however. All political polemic, for instance, is hinged upon the notion of the power of concentrated and driven will against material conditions, as is all revolutionary politics. We may not be able to take will out of the world, but we can direct it within the world; in this way, it can be seen as force vectors within the ocean generating the specifics of the fluid dynamics of currents and waves, the "active" component within any physical system compared to the "passive" components of, say, the viscosity of water, the pressure of the atmosphere downward on the water, its chemical tendency toward forming a tense skin, etc. The Superman of this story, Dunn, is measured by taking a common man and imbuing him suddenly with enough power to make all of his will attainable if he so chooses. In so doing, we get an image not just of the wisdom of the character, how far ahead they think and plan and account for, but also a depth of character. Most times in life, our desires, noble and ignoble both, are checked heavily by our capacities and awareness of our limits. You might fantasize about extreme political violence, but the reality of being killed before doing much of anything keeps you at home on your phone, where similarly your desire to end hunger in your community is likewise thwarted by how overwhelming the idea of building out effective structures to consistently address the issue is. It is wrong to say that limitless power gives us a clear image of the moral character of the will because, again, at all times will is attenuated by circumstance, and capability is one of those circumstances. We don't know within ourselves, in a true sense at least, how many of our passing idle whims and fantasies would be gainfully taken up if we knew they could be achieved and which would remain in the mind. The shift in amount of power tips the equation so thoroughly that we inevitably are only seeing an abstracted image rather than a deep insight into character. We may as well be considering the same you but born with billions of dollars in wealth; we have changed only one variable, sure, but the knock-on effects are so profound we may as well be considering a wholly separate person. Especially when we link this with the little paradoxes of the continuous consciousness and the question of whether the us we are now is strongly identifiable with the us of ten or twenty years ago.

This view of the Superman within "The Reign of the Superman" is a cynical one, one that takes the easy and oft-repeated position of the corruptive nature of power. It is less that this notion is wrong as much as it is uncomplicated and presents a very simplified view of the depth of the issue of power, will and the superman, finding the first difficulty of whether the person who receives it would do good or not and surrendering to the easy cynical impulse. But it is one that would, in less than a decade, be invested with a great deal more activity and internal complexity.

2

There is a brief stopover before we reach the iteration of the Superman we are most familiar with. There is a period between the prose piece "The Reign of the Superman" and the debut of the proper Superman of roughly five years where the young Siegel and Schuster were hard at work within the comics world. While they developed the rough elements of Superman as a character and even drafted a number of daily strips for papers to shop around, they had little luck finding a publisher for years. In the intervening time, a bevy of elements that would come to be folded into Superman as we know it were laid out by various other creations of theirs. They created a character named Doctor Occult, occasionally repackaged elsewhere as Doctor Mystic, a mystic detective of sorts that went on adventures dealing with the spiritual realms. This plays off of the then-fifty year obsession with spiritualism that had kicked off in the late Victorian era which saw in turn the resurrection of the ghost story and the gothic novel as formal structures. Someday I might enjoin my pen with those like Adorno who have commented on how this intrusion of the deeply immaterial upon materiality primed the world for the fascism of the 1910s and onward, which couches itself in a hybrid of highly-contradictory worker grievances and grievances of capitalism wrapped in heavily racialized and supremacy-minded identity politics imbued with supernatural heft, but not quite at the moment.

The intrusion of the supernatural into the metaphysics of the Nietzschean superman is a wickedly ironic one given Nietzsche's own strident stance against the immateriality of the spirit as envisioned by religious faith. His oft-quote, oft-misunderstood sentiment of the death of God has less to do with a theological reality shift per se and more a commentary on how religious law had for centuries if not millennia been the fundament of the ordering of society and personal ethics, at least in a nominal sense. The rising wave of scientism, brought about in large part by figures like Kant, Descartes and Hegel despite all three being devout Christians struggling in vain against the atheistic tide of their interrogative creation, meant the clear and inevitable erosion of the metaphysical truth-value of first Christianity but later most religiosity in general as a metaphysical underpinning of the world and with it the justifications for the moral, ethical and societal frameworks we had built up. Cowards, idiots and fools would cry about this for centuries afterward, including up till now, saying that we can't assemble a morality or ethics without an ontological ground. This is stupid and not worth more comment. Nietzsche, however, predated a great deal of later modern and post-modern struggles against this collapsing star around which we had set our world in orbit, with his strident argument for the supremacy of will and power being deliberately amoral, as in outside the ken of morality as a structure, but also something that fundamentally and obviously did exist. God may not be real, but our presence and power and will and action within the world, its history and its materiality, are real, and from that fundamental reality we can build our a world. As Nietzsche saw it (at least in part; he, the system-breaker, was confoundingly and frustratingly contradictory, even if this same element is what redeems his worst and dumbest thoughts and provides a powerful precursor to post-modernist logics), the fixation on external ontics to ground the world as a fundamental nihilism that had to be overcome. This was a weakness of the heart, a cowardice, that we seek not to active pursue and forge will, good, evil, might from ourselves but have to and can exclusively receive them from outside. It presumes that the human life and the material world has no value whatsoever and that all value arises from and is exclusively stored within the spirit. This provides both the chains of abuse of every religious structure that engages in it as well as the abrogation of all human power, be it the revolution against oppression, the becoming of self or even acts of evil and wickedness; that those things exist means by its nature that the will of heaven cannot be so ironclad and potent as to preclude it. Fascists seize up both the image of the radical self of Nietzsche and their spiritualism as again one of their many cryptic contradictions which, rather than generating potent sparks, here just dissolves into chaotic foaming nonsense.

It does, however, show that such things were on the mind of Siegal and Schuster. It was through them, in fact, that they put to pen the character Zator, a minor character in the mythos of Doctor Occult/Mystic who, nonetheless, was potentially the first caped superhero to take flight. This is a pithy imagistic element perhaps, but an important one; Superman did not fly in his earliest incarnations, but it is Superman in flight that is a key element in completing the picture of Superman in a sense of symbolic function. The airborne god, hovering before our vision, cloaked in the corona of the sun, is an image of heft that extends beyond the obvious Christian world. We can't assemble the complex myth-figure of Superman without it. Likewise this encounter with the magical would come to bear upon Superman as well in years to come, nested within the symbolic weight of his weakness against and susceptibility to all magic. We will return to this, obviously, in due time.

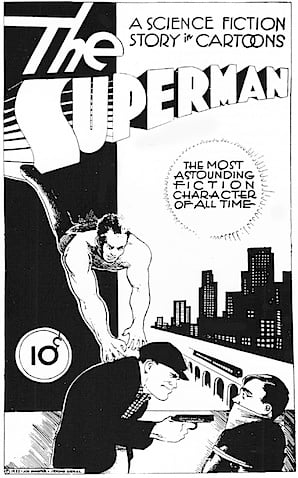

In the midst of this period, S&S also leaned in to creating a series the then-popular genres of heroes, such as the detective Slam Bradley, the pirate Henri Duval, the police book Radio Squad, and the super-spy Bart Regan. In the midst of this, however, they also penned a full-length issue of an original hero, a shirtless and musclebound genius detective known as The Superman.

This iteration of Superman is a crucial missing link in the evolution from the character's past as a hybridized form with his later villain Lex Luthor interrogating the failures of the Nietzschean concept of the ubermensch especially in a vacuum of ontological grounded morality and the later much more philosophical brave and robust character. Frustratingly, we know little of this middle form. The book, in which the detective known as The Superman clad in a dark cowled cape stalks rooftops as a detective of incredible mind and strength, predating Batman (their creation Spy also was published in Detective Comics #1, beating Batman to the punch in the book where he debuted) by a number of years, featured a more complex view of the Nietzschean question. Being interlaced with the worlds of noir and crime fiction of the day, The Superman likely, must as in their other detective work, straddled the line in terms of an objective morality. All that survive of the book is one completed cover sans colors and one sketch of a potential cover; on the sketch, The Superman is proclaimed as "a genius in intellect, a Hercules in strength, a nemesis of wrong-doers." It was common for these types of tales at the time to feature a character often on the wrong side of the law working to do what was right even against a system that often seemed agnostic or even vicious in its treatment of the common man, allowing or in some cases causing and encouraging wrong-doing and criminality. This is a somewhat more complex vision of the vigilante than the common libertarian dream of hyperviolence, predicated not necessarily on a cynical view that society cannot adequately answer questions of societal distress, crime and restitution but that its current iteration, powered by plutocrats and imperialists and the political class, simply doesn't care to, often wielding these self-divisions to maintain their position. It is thus the role of the super detective often to find restitution not only for those wronged by criminals but also for the society failed by its police, its politicians and its communal structures. This iteration of Superman was turned down by a number of publishers; in a fit of rage, Siegel burned the completed pages, with only those covers surviving.

The connection between this character and the Superman was know, let alone the previous villainous interpretation of Superman they put to paper, is not an abstract one. The lettering for the name of the character is a near duplicate of the one later used for the Superman we know, with the sense of dimensionality to the letters and the way they seem to be pushed further back the further along the word you get. Experiments with lettering as a design and artistic element had begun to be explored around this time, culminating eventually in the "big boom" of diagetic/non-diagetic design elements of Will Eisner, for whom one of the major comics awards is named. Schuster's design in this time period makes the connection clear by means of that early position; in a void of other competing approaches to the design of a character's name along with its clear mirror in the later character, the correlation between the two becomes obvious. Likewise, S&S had begun at that point thinking about how they might adapt their earlier character, which compelled them greatly, into a heroic sensibility, feeling a great sense of potential in those waters. "Reign" was produced and published in early 1933 while this later shirtless super detective Superman was written and shopped in late 1933; by summer of 1934, they would in a whirlwind create the character we know now, along with several days work of completed strips and even more scripts, shopping and failing to sell the character until its eventual debut in 1938. This gap of conception, where the earliest work of the character predates several of their creations and iterations on moral and ethical questions while setting aside temporarily their symbolic fixations, creates a fascinating and fruitful sudden evolution in the character when their earliest work ran out and they suddenly, years later, had to create new adventures for this character whos development had been brewing quietly for years.