Before Death: An Incoherence (Part 6)

VI

The most immediate effect especially in a positive sense my unremitting death fixation brought about was a radical shift of politics. Suddenly, the notion of tolerating a little death became repugnant to the extreme. Stripped of divinity, given only the wild dark eternity of the perfect silence of death, all suffering in brief lives became torments within my mind. We were stealing the finite time away from those who could never have it returned, filling it with sorrow and deprivation rather than love and joy, and calling this political efficacious, lamentably necessary at worst and ecstatically necessary at best, or maybe vice versa. Liberalism as a structure fell away completely; its refusal to move away from the immense cruelty and modern slavery factories of the contemporary prison landscape had galled me even when I considered myself a left-leaning liberal, this ungainly sin marking us like a pox that we too hated the poor and the deprived and punished them for acts emerging from the conditions of their lives. One of the real benefits of my brother putting me in the presence of so many genuinely bad people within the drug world as I was growing up is I met so, so many who were not. People who were trapped, who used drugs to escape worse conditions in life, people who had dreams and desires they either didn't know how to fulfill or had the pathways taken away from them entirely. I had not yet had occasion to know these people to die. That would come not much later in my life. But I was still filled, even with my own traumatic and complex relationship with substance usage, unable to turn my eye away from the wounded and restrained goodness I saw in that lay humanity.

The first great political cause I took up as a child was the blood diamond trade. It was and is a horrific industry to me, one generated by the false scarcity of largely Dutch companies (or companies founded as Dutch companies before shifting their nationality in the complex Derridean mask game of corporate identity politics) wielded viciously against Africa. The intent to keep the most resource rich continent on the planet deprived of the wealth needed for it to establish itself as truly independent was clear to me even as a kid, but hadn't yet reached the peak of inward intensity I now feel regarding that topic. The immense barbarity carried out against effective slave labor, a term I had to define for a girl in my class in high school who couldn't fathom how wage manipulation and work opportunity manipulation could force someone into working conditions designed inevitably to kill them, became a burning coal in my belly. One great benefit of autism is these affects become sincerity near immediately; I am not African and have no claim to that identity, but the thought of people being mutilated for rocks that are not even especially rare to benefit nations beyond them while leaving them destitute was so obviously abhorrent that it lit a fire in me. Prison reform was the next great cause that formed an inferno in my head. This one was more personal; I have never forgotten the man in my family AA who was gunned down by the police, as justifiable as the narrow action may have been. It reeks to me of a world that abandoned that man, abandoned his family, and allowed the issue to complicate until that death was inevitable. I feel this way as well about the loss of my father. On paper, as decent to-do white folk in the 90s and 2000s, we had the means to address his issues. But a broad social coldness toward addiction, an unwillingness to face the ugliness brought on to families by it and even when able to view it, an unwillingness to bend toward any level of compassion that might alleviate sorrow rather than add castigation felt like a concommisserant element of my father's inevitable death sentence. My mother, my brother and I all had very different but equally complex relationships with the man; no matter the complexity, we were united in how devastated we were. That I could expand this to friends of mind picked up as kids and tossed in jail or forced rehab for drug possession without any interrogation as to what might have caused it, no interest whatsoever in the underlying pain, trauma and anxiety of being that was so abundantly clear to me as their friend and peer, felt willfully negligent, a way to brush the embarrassment into the corner rather than to compassionately address the problem.

This sensibility only exploded within me after my breakdown. I could not love myself. I dared not to. That was a scarred and burned black effigy of what once was a body, wrapped in the cold steel of car crashes, the ambient klonopin and alcohol floating through my blood, and the passive perpetual desire to grab a noose, a chair, a gun, and give them something to remember me by. I could not however hold this enmity toward others. That was my line. I took all of the hate that had fueled me for so long, the bitterness and the agony and the alienation and the wild sorrow, and I swallowed it up, pointed it like nuclear weapons at my own heart, because I no longer could bear to point it toward the world. I had become overwhelmingly aware of my own pain, had become increasingly conscious of its origins, and while I was trapped between being unable to forgive myself for its creation and unable to forgive others for what had produced that shrapnel in me, I couldn't bear to be part of that process outwardly anymore. Anything that reminded me of those cycles of inducement of pain had to go, burned out viciously and without remit. I was watching Occupy on my computer through Twitter, reading books like Late Victorian Holocausts and Shock Doctrine handed to me by my far-too-smart friend Justin, who himself had recently embraced communism as the only logical response to the vast structures of violence which covered the world. We already were stridently anti-queerphobic, as much for political reasons as reasons of community protection, and feminism in us was latent and struggling to articulate itself gainfully. The embrace of communism is what broke open those final doors.

I began voraciously reading as much theory as I could. Those outside of the world of theory I think can view it, understandably but wrongly, as an intellectual exercise. This is impossibly wrong. You do not approach those spaces because you are a cold abstract intellect, or at least you do not thrive in those places. It requires to some real degree a beast-nature, a serpent crawling on its belly, a dissembling madness where the world no longer makes sense to you and in your frantic quixotic quest toward sanity you must forge anew all the structure and superstructure with which one might experience and understand the world. My mind had been swept away from me by might waters and I was left with nothing save the insatiable hunger for self-destruction, following my brother and father and grandfather and the cousin of my father who'd killed himself and my great grandfather the devil, on and on. What existed to save myself was this incommunicable task, to diligently and with the mighty force of passion, the one inextinguishable force alive in my breast still construct again a means with which to understand and love the world. I bought Sartre and Lenin, Hegel and Minh, Mao and Althusser. I was chasing the ghosts of intellect and the spirit of the political across time. Judith Butler fell in my hands and presented to me a mirror of my gender, my desire, that frightened me. Angela Davis and Audrey Lorde directly challenged my notion of love, nominal love, in a means of bringing it in alignment with that greater inward love I already knew existed. I still found myself unable to re-enter my body, blockaded by trauma done, viewing us as two separate entities. But I had begun to soften on my antagonism toward the body. After all, when my mind abandoned me, encouraged me to die, it was my body that preserved me. It was my body that never gave up on me. When I could not continue, when my heart was too broken to exist anymore, when in tears I begged for the permanent quiet of the grave, it was my body that solaced me and held me close. So too was it for others. My heart was bursting open in a manner that could not be undone even if I wanted to. Feminism flowed in, as did queer theory, racial studies, anti-imperialism, anti-capitalism, and the only potential solace to those harrowing pains, communism. I was still incapable of accepting flaw and as such was incapable of accepting humanity. Those confrontations with self would come later.

Still, trapped in my cycles of self-abuse, the waves of alcohol and drowning myself with pills, I could not self-actualize. I grew in passion, the force of my mind throbbing uncontrollably behind my lids, but I was still unable to move.

It was in the throes that I returned to OkCupid. This beast inside of me, not human, wanted to go out into the world. If I was going to be burned alive within my mind and heart, if I was to succumb to the fires of the world, then I would step out and burn in daylight. I had become tender, my flesh torn away, a living bundle of raw nerves. I wept with love like a flower perpetually full of nectar; I believed myself often dry, withered and without life, but I could not see at the time that life was pouring out of me as if squeezed, like I was attempting to expel all of my selfhood out into the world in a furious burst before collapsing dead. I was sitting in bed, having shifted from my old bedroom to the guest bed, feeling a kind of mental collapse sleeping again in the same room and same bed I had during the childhood I had before my life seemed to catch fire. I was up late at night listening to goth rock, Primary Colours by the Horrors ripping through my speakers. I saw a woman named Molly appear in my search and saw that she was online, so I sent her a message. By this point, I had given up on romance, declared myself incapable of love or being loved, but my passion for art remained, and so I would read diligently the novels and films women listed and offer suggestions of potential new works before closing the tab. I recommended her some records and clicked away. She responded shortly after saying she loved them and asked if I had more. So began our romance.

It lasted on the calendar a mere month. This to me even now is an impossibility. We felt like a binary star system rotating around each other. She was recovering from traumas of her own inflicted upon her, far from her family and attempting to establish a life for herself in Northern Virginia, while I was near-dead and emaciated. We went on one date, then another. Our natural intensities were quite high; we were both creatures spat back up from the pit. So we returned to her place, intending to watch a movie, have dinner, make out. Instead, Jose Cuervo Silver came out, small glasses, and bottles of klonopin. In the midst of obliterating our minds, heaving a deathward psalm in soft suicidal indulgence, I lurched like a demon toward her bookshelf. I had glimpsed Camus, a figure that I was still unwaveringly fond of. In the depths of my post-psychotic inebriation, I was freed enough of the shackles of life to be able to lift the book, collapse to my knees in a drunken stumble and begin half-shouting "The Myth of Sisyphus" as dramatic dialog. I kept pausing to stare at her in the eyes, to convey that this was why the beast of me still moved. I could be patient. Death would come one day anyway. I had to expel this thing, unnameable, from my belly by the means of my mouth. I must have been crying because she stood up, walked to me, sank down on the floor next to me and kissed my eyes. I kept reading and weeping. The tequila and benzodiazepines eventually reached their activation in my blood and I collapsed into sleep somewhere in her apartment. That was the first time I'd slept over.

We became inseparable. I was unfunctional without her. I had to go see her, or have her visit me, see my mother, for me to feel something, like the limb waking up and returning to the throb of blood and the crispness of the cold of life. I would read the books she had stacked on her bookshelf in the corner and we would watch movies. We would make out seemingly only while blisteringly drunk; we would make dinner in her small kitchen and eat at her tiny table. It was in her apartment that I took an idea I had come up with, a great big conceptual novel sequence, science fantasy spanning the 1850s to the 2050s inspired by everything in my head from Martha Washington by Frank Miller to League of Extraordinary Gentlemen by Alan Moore to the apocalyptic prose of Crowley and the conceptualism of The Quincrux and more, just a heinously, impossibly ambitious project. She rewarded me with kisses. We would break plates on accident; I would wake up in the middle of the night and do her dishes for her as a surprise when she woke up. We only ever slept together while I was too drunk to remember, a thing I don't blame her for because we were both in the misery pit. Then, one day, she broke up with me, told me I was going nowhere in life and she wanted to go somewhere and to thrive. She'd met a chef, and he had a future, and I didn't. I didn't even have my degree.

Earlier, within the month, my uncle and godfather Thomas had sent me through my brother a leather jacket, his old riding jacket from when he would race motorcycles before his wife (wisely) made him sell the bike to preserve his life. My brother didn't fit the jacket, so it was offered to me. I received a jacket that was heavy like battle armor, thick leather black but with bronze showing through. Wearing it, I felt transformed. Gender, as I may have discussed, has always been a lingering phantom to me. Manhood certainly did not fit, felt like a bad masquerade or a Halloween costume, but womanhood likewise felt an obvious mismatch. I have worn dresses and skirts, makeup and heels, I had changed my voice and pursued aberrant desire, but none felt closer to some true sense of self. I felt alienated from Self, the fundamental concept, able to Be within the world but not able to Become and, as such, deprived of a name, remained unknowing of what I was. The leather jacket changed that. It wasn't a permanent change, obviously. But suddenly under the leaden weight of the jacket that had saved my uncle's life more than once in crashes I felt a union of the razor thin barrier between myself and death, that lingering sense of familial curse with mocking Satanic laughter, and an impervious toward the slings and arrows of the world. After all, only I will kill me, and while I know not that coming day, I know it will not be by the hand of another. In such a way I am rendered free from harm, forever.

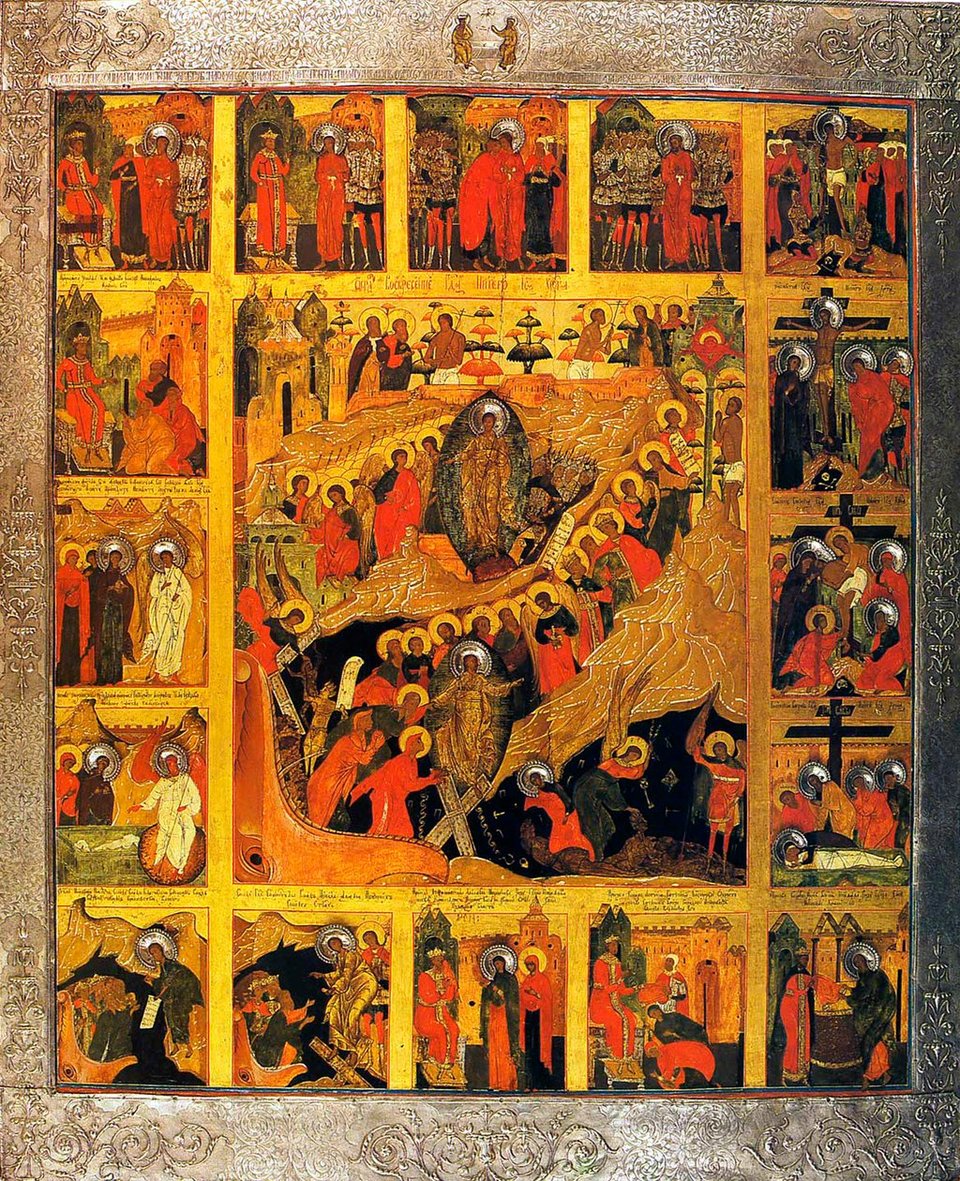

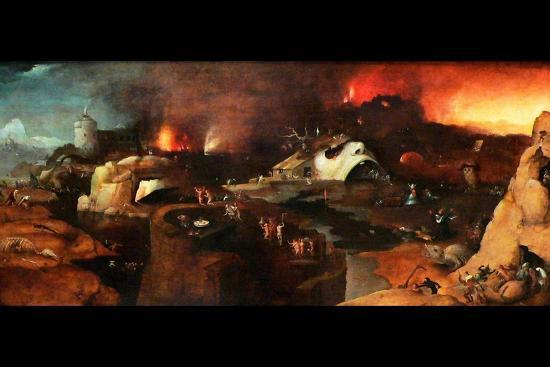

There was a window within this peaked darkness that I descended again into what I can describe as a religious psychosis. This time, it was a healing one, mercifully, against reason, one triggered by extreme alcohol and benzodiazepine usage that put me briefly into the eyes of God; or, rather, beside them, sitting on a pillow next to the divine witness itself. It was not that I thought I was becoming one with God; instead, in a literally throbbing fit, between the withdrawal symptoms of my anti-depressants and the waves crashing against my body from the inundation of wine and whiskey drunk alone at the seat of the table where my father too drank himself to death and the pulsating numbness emergent from the sedatives in my blood stream, I suddenly burst into tears. It all became abundantly clear to me: I craved, beyond any shadow of a doubt, grace, to be forgiven. I am an atheist and was an atheist then, so my notion of finding this within some divine favor was scuttled before it began, but the profound thing for me was the sudden return of understanding of the base impulse that makes people religious. Some acquire faith due bluntly to a fear of hell; others, from a more generalized fear of dying; yet more from a specified desire to go to heaven. None of these internalize the heart of faith, be it Islam or Christianity or Buddhism or Shinto or any of the other faiths that have especially that kind of hierarchical approach to the afterlife (even if several dispel that hierarchy overall). Aware of my sins, no longer written in a religious sense but instead through the secular terminologies of failure, harm, letting others down, forsaking myself, abandoning others, descending into a pit I once judged harshly and that harsh judgment itself, I now felt as though I could not reasonably be forgiven by the world. I had been rendered a wretch, a failure, vermin; the way we view the homeless and the addicted and the former or even current criminal is akin to how we see the cockroach or the invasive mouse in the wall, something to be disposed of without mercy for the betterment of the home, a sentiment that makes sense to all but the thing that is to be killed, especially when it too simply years for a dignified life. Forbidden from earthly forgiveness, I became in sharp revelation aware of the bone-deep desire for a supernatural or theological forgiveness. Alone, as abandoned as I had abandoned others to reach this point, I now understood the intense desire for someone who would always be present, in love without judgment, there to guide and aid and succor you rather than to punish and castigate. Devoid of some means of acquiring these things I so needed for my own very real earthly salvation, I became intensely aware of the necessity of grace, how the extension of grace is the first mystery, as it is given without expectation and without aim beyond itself. You see suffering and extend a hand. The rationalist will tell you to measure those moments; a heart aflame with love can no longer listen to reason, which abandoned it too in its moment of crisis, and now must extend downward the hand that at times arises mysteriously from above, be it from a friend, a neighbor, a lover, or a stranger. I called over to my house my friend Matt, who to his credit never one abandoned me in that pit, his former Catholicism having burned deep into his flesh the spirit of charity and grave, and administered my newfound sermon through the threshold of drunkenness. He took me to Applebees where we played Rush on the TouchTone jukebox and ate cheap boneless wings before he returned me to my home to sleep.

There was a spark in the darkness. Beneath the belly of all that grave dirt, amidst the mud made of my father's ashes and the wine I was using to wash them away, there was suddenly within it a seed of light. I wanted to live. This was not in contradiction to my desire to die, to kill myself. These were antagonistic forces seeking synthesis in my belly. In my awareness of death, in the fervency of my desire for my own total destruction, I had re-encountered a deep and abiding love of the world. It is one I inherited from my father and, like him, would lead me to no end of trouble.

A lingering aspect of the time as a Christian was my desire to live a Christ-like life. I feel that most who take up his name as their faith misunderstand this, looking to wield laws like cudgels and punish those they deem unfit. This is gruesome and despicable to me. We are called, if we are to believe, to not castigate but to sit with the sinner. We are to be the shepherd's crook leading them back to the flock. There is no language for when to abandon a sheep because there is no circumstance where this is allowed. The task of love, its perpetual task, is to reach out in grace to extend the mercy you yourself received, to replicate the miracle that saved you from the abysses of the world and the final abyss of eternal death but pointed toward another. There is no end terminus for this cycle. After having brought succor to one, you are not called to rest and wear laurels for your accomplishments. You are not even called to call attention to yourself to seek accolades. You search your heart, find the next in need of comfort and aid, and you help. This means sometimes sitting with people who have done awful things and doing the long, slow work of helping them amend themselves, with setbacks and remissions, with patience and love. To show love toward those who have done harm is not to deprive those victims of love as well. You are seeking actively to end the cycles of harm. A great issue with victim-oriented response is it is always by nature post-facto; there must be a crime, a wound, a victim for you to work with. We must be proactive with love and grace. We must seek to locate those who may or who already have committed harm, even great harm, and extend to them the loving mercy we would wish to receive. We must do this for them as well as for all who may have been hurt by them had we not. You can never abandon a human life and declare it deprived utterly of value. Not when you have been once declared as such. Not when you too have been abandoned to die and only by the witless merciful grace of another were you able to begin again. This is why in my life I forgive and forgive and forgive, even as friends chastise me for it, blame it not unduly on the constancy of elements of my suffering. I do not care. Genuinely, I do not. I am called to be this way because it is what saved me. I cannot turn my back on that. Even when I most wanted to die, by my own hand, I suddenly found a fire that said I could never forsake this thing within me ever, ever again.

Confronting this made me realize then as it has recurrently since that I carry God within my heart. I do not believe in spirits or souls. I do not believe in heaven or hell. I do not believe God is an extent force in the world, a creator, a judge. But this shadow is buried within myself, the fierce eye of the conscience that I can call perhaps God. People tell me, more than make sense to me, to abandon this. I cannot. I feel a burning in my heart equal to all of my other passions when I know that I can do something but have not. I refuse stridently and stringently to be a bystander to my life, to hurt I witness, to those who need help whether they are victims or perpetrators. In my heart, I can judge as much as I may like, but if I stay my hand out of this sense of malice and self-righteousness, I will lay down at night hating myself. After all, I was abandoned to die by such things. I was ejected from church, my father thrust unceremoniously from social circles and thus we as a family as well, my father inevitably laid within the grave and all the dissembling within my mother's mind and my brother's as well that would eventually lead to his own divorce all came from that same withholding of grace and mercy, whether justified or not. I could not, cannot, stand this. It is what drives my political fervor. It is why the miseries of the fascist government of 2025 do not hurl me into despair. This is as fundamental to me as thought and writing. What value would my passion be, my life, if I shortshrifted this most? What use would there be in me having clawed back toward life? I did not return from the shores of the dead idly and without purpose.