TESTED: The Onion, or, Powers of Ten (Tested's Version)

Have you ever seen the Powers of Ten video1? To me, it is iconic, but I've recently learned that not everybody is familiar with it. I can't remember the first time I saw it, so it was probably in high school and it has stuck with me ever since.

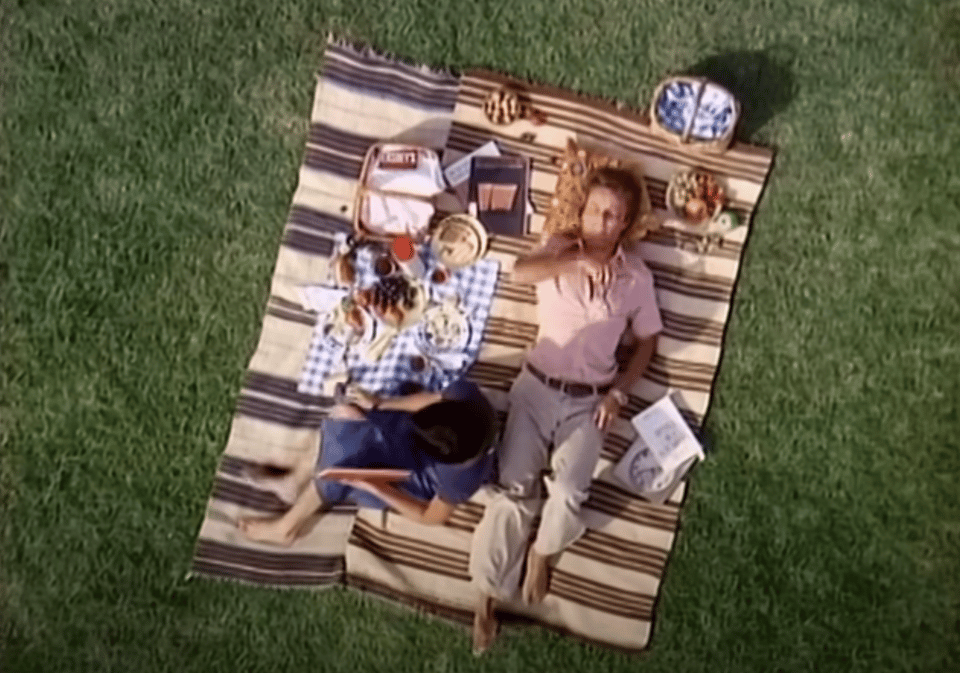

The premise is pretty simple — every ten seconds we get ten times further away from the couple on the picnic blanket. Then, things reverse, and we zoom back in and get ten times closer. Sounds kind of basic, but I promise you it's worth watching — there is something totally mind melting about seeing scale happen in real time. About zooming out and out and out and then back in. About being faced with visual representation of how we live in this tiny sliver of scale. That all around us there are entirely different sizes, ways of living, movement, concepts of time, and more2.

Powers of Ten positions scale in the realm of physics — an interlocking series of spaces, connected and yet sometimes impossibly different from one another. But I think the reason that Powers of Ten really captures me, is that this premise — slowly zooming out from the individual to other scales — is a useful way of thinking about stories too.

As journalists we tend to look for characters — individual people with complex lives and preferences who are making choices and reacting to the world in interesting ways. We center our pieces around these characters. We want you to meet them, get to know them, love them or hate them (depending on the story). But ideally our stories are about something bigger too. Ideally these characters embody something more — something that exists at the next scale.

Making this jump is really hard to do well. You don’t want to overstate how much any one person really represents the whole. Christine Mboma doesn’t represent all athletes with sex variation, nor should her case be used to make conclusions about testosterone or the impact of lowering it with drugs, or anything like that. But also, her story does lead us to bigger questions and reveal deeper truths about how we think about the world, how power works, how systems are organized. How do you make that jump responsibly, accurately, and convincingly?

The final episode of Tested was one of the most challenging ones for me, in part because of these questions. There was still so much we could have said, so many stories and angles we could have brought in. We talked through a huge number of formats and elements of that last episode. At one point, I wanted to have a chunk of the episode be a live conversation with people who agree that inclusion mattered, but might not see completely eye to eye on how to make that happen3. I resisted including the birding scene for a while, because I was worried it might be too self indulgent.

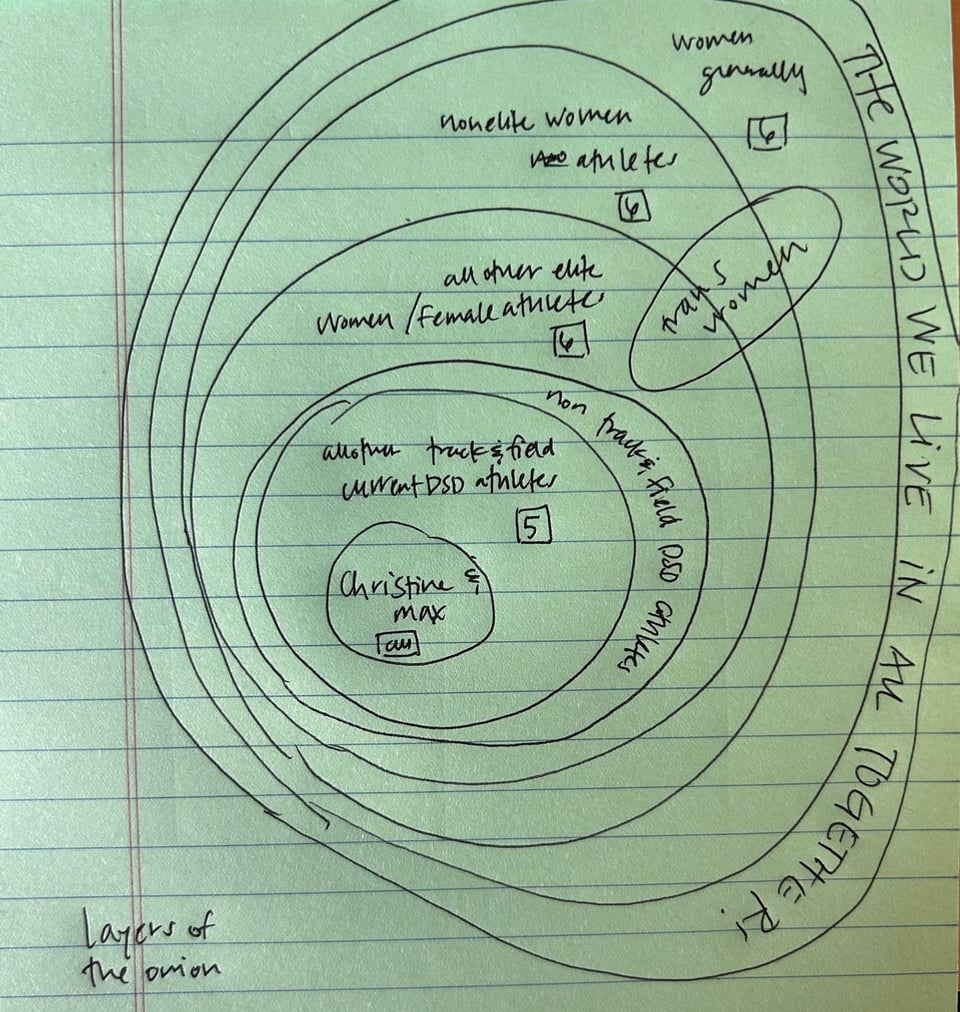

And at one point, I pitched a version of the final episode that was, basically, Powers of Ten (Tested’s Version). I called it "The Onion."

The idea was to start with the women you got to know over the course of the show: Christine, and Max. They're the ones sitting on the picnic blanket, on the side of the lake in Chicago. And then, we'd move out, and out, and out, peeling back the layers of impact and influence that these policies have on people.

The goal was to show something that, if I'm totally honest, I don't think I did a good job of getting across on the show in the end: that while these policies might seem hyper specific — influencing just a handful of women at the most elite levels of sport — the core ideas that underpin them can (and do) impact almost everybody.

And I wanted to share this version of episode six with you all, in case you were curious, because I think it still is a useful exercise or perhaps helpful way of thinking about the story.

The Onion

At the center are our characters — Christine and Max, who you've gotten to know. Who, at this point in listening to Tested, I hope you've come to care about and root for. Here we'd hear the resolution of our story — does Christine qualify4? What happened at Max’s lawsuit5?

One layer out from them, are all the other women in track and field impacted by these policies over the years. All the women with Y chromosomes told to fake an injury and leave. All the women who refused to do a nude parade, and who are still being used as examples of cheating without any evidence. The women who got surgery without realizing the long term effects. The women today who have given up on running. The dreams that were ended due to these policies.

One person we spoke with, but who didn't make the final cut, is Canadian speed skater and CBC commentator Anastasia Bucsis. I asked her to describe what it's like as an athlete to find the zone — to really hit your stride, or feel like you're performing at your peak. "It's the greatest thing you will ever feel," she told me. "I would liken it when you're at the airport, walking on the moving sidewalk, and you have a great song in your headphones and you're like, ‘no one can touch me.’ You're passing people left, right and center. It's that feeling times a billion. And you're you're doing that in something that you love. You only have to feel that moment a few times and you’re hooked forever. And I still dream of it, to be honest. I'll never feel that good. I've been retired for six years, but, if I really close my eyes and think about it, I can transport myself right back to the oval on on the good days."

I think of this quote because this moment of being on top of the world — on that moving walkway, time a billion — is often the last thing these athletes feel before they're told they have to stop. Caster, Christine, Beatrice, they were all flagged likely in part because they were in the zone. They were performing well. Then, suddenly, someone was telling them that they can't have that anymore.

I asked Bucsis what it would be like to have that feeling taken away from you. "I can't, I can't imagine," she said. "It just gives me a pain in my heart because I... It makes me emotional even thinking about it."

One layer out from these women, are the women with sex variations competing in other sports outside of track and field6.

One thing I heard from a handful of people while reporting on this topic, is that smaller federations were looking to World Athletics for a guide. Most International Federations (IFs) are small and poorly resourced. They don't have the money to fund studies to evaluate what advantage intersex athletes might or might not have in their sport, and they certainly don't have the money to bankroll a series of expensive international lawsuits to defend policies that regulate those athletes7. But World Athletics does, and so what I heard was essentially that if WA is able to successfully defend these rules, it would encourage other federations to follow suit and copy them.

And there are, of course, a handful of athletes with sex variations in other sports. Barbara Banda, for example, was temporarily removed from the Zambian national team, but eventually reinstated because FIFA doesn't have a policy in place that regulates DSD athletes. We saw after Tested aired the fracas around boxers Imane Khelif and Lin-Yu Ting (although, to be clear, we still do not actually know if these women have any form of sex variation or not).

Other athletes choose to leave the sport because they know that this will likely come up — policy or not. The golfer Kendra Little, for example, decided not to turn professional because she knew that she would face scrutiny over her body.

Zooming out from this layer, we move to the non-DSD elite female athletes, who are being told that it’s simply not normal to be that fast, that women can’t possibly be this good, or that strong. We're seeing more and more female athletes being accused of secretly being men simply because they're strong, or fast. Ilona Maher has talked about this, about how people online talk about her body and her strength as inherently not womanly. Katie Ledecky is now being accused of being a "biological male." There are so-called "transvestigations" happening into athletes all over the world simply because they are strong.

One layer out from that, are the non-elite athletes who are just trying to play a sport for fun. Women who know they’re never going to the Olympics or turn pro, they just want to play on their high school or college teams. You heard on the show Dr. Casey-Orosco Poore raise questions about when these policies begin. "I am a pediatrician, and I do think about how these elite sports spaces will inevitably affect vulnerable children,” they said. “I think about being an intersex child, getting into sports and thinking, 'wow, the worst thing that could happen to me is that they either find out I'm intersex or I end up being intersex, and I didn't know and I can't play sports anymore.'"

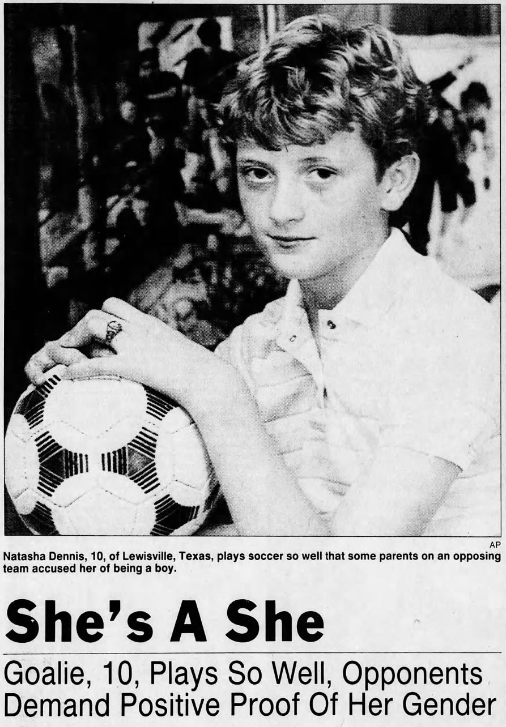

Here is where we would bring in stories about parents accusing girls of being boys, because they were "too good" at sports. The example I always think about is Natasha Dennis. In 1990, at a girls’ soccer game in Texas, 10 year-old Dennis was the star goalie. At halftime two fathers from the opposing team demanded proof of Natasha's gender. “They expected her to go into the ladies’ restroom and take her clothes off in front of some stranger,” Natasha’s mother told a reporter at the time. Fortunately, the gender check was denied, and the fathers were suspended. As for Natasha, she was quoted as saying, “I think they should go somewhere and check and see if they have anything between their ears.” A pretty sick burn for a 10 year old, in my opinion.

Moving out from there we have all women. Women who will always be subject to scrutiny if they’re “too good” or “too much like men.” This isn’t just in athletics, it’s also in art, and business, and law. There are endless studies about the ways in which women and men displaying the same behaviors are not perceived equally — women are seen as judgy and pushy and rude, where men are seen as decisive leaders.

"I think society will put women in a box," Bucsis said. "Because how could a woman be so strong and powerful and amazing? It's not my quote, but there's that sentiment that if you're an amazing man, you become Superman. And if you're an amazing woman, you must be a man."

On top of this, is the the ripple effect of the idea that women need to be "protected," and that men should be the ones doing that protecting. "Undergirding so much of this is this idea of women's inherent vulnerability," said Katrina Karkazis. "Women as victims. Women as needing to be protected. Women as inferior. Women as weaker."

All women are impacted by these ideas about what a woman is, and who gets to decide.

And finally, our last layer, is humanity. Everybody! Men are also impacted by these ideas. The flip side to the idea that women are inherently weaker, vulnerable, fragile is that men must be big and strong and aggressive. This is one of the core elements of toxic masculinity and its impacts spread far and wide. Nonbinary people (hello!) who are erased completely from this conversation. Kids who are trying to figure out who they are and what they’re allowed to be and whether those two things will ever match.

Zooming all the way out, this story makes us ask: What kind of world do we want to live in? A world where an organization that is beholden to no one, can force you to take a test, and based on that test tell you that actually they know more about who you are and what you are capable of than you know yourself? A world where you have to be a certain way, where your body must match a cartoon drawing? A world of violently imposed hierarchy that negatively impacts everybody?

I think we can do better than that.

So that was my idea for The Onion, or Powers of Ten (Tested's Version). Obviously we didn't do this! And there were good reasons not to. But I wanted to share it because it's one of the things I actually wish I had better communicated on Tested — the ways in which this topic really impacts everybody not just a tiny group of elite women.

Footnotes

The full name of the video is Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero, and it is actually the second version of the concept made by Charles and Ray Eames (yes, of Eames chair fame). The first version was made in 1968, and called A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of Things in the Universe.

Ed Yong, the iconic and brilliant author of I Contain Multitudes and An Immense World is actually working on a third book right now about scale and I am foaming at the mouth with excitement about it.

The idea here was not to have "people from both sides" debate whether folks with sex variations were really women, or something like that. But rather gather up smart people who might disagree about what should actually be done. Some folks believe a third category really is the way forward. Others argue that trans women should indeed be expected to lower their T, but intsex women should not. A conversation among these people who all have the same core goal of inclusion could be interesting.

At the time I wrote this outline, we still had no idea what would happen with Christine. In fact, we didn't know only a few weeks out from publication date. It was... very stressful. Someone recently asked me and Alison MacAdam how we felt about having a kind of "disappointing" ending to the story. Alison's answer was funny, I thought, which was basically "I don't think it was disappointing, I think it was true. We have to go with what happens."

This part of the final episode was probably the hardest for me, in the end. The fact that I couldn't (and still can't) share with you more about that moment in Switzerland kills me. But as a reporter I have to honor confidentiality to sources.

One challenge in this structure is that I couldn't quite figure out where to put trans folks. Trans athletes obviously feature in several layers, since some of the policies that exist impact them too (or, as is the case with World Athletics, there are corresponding trans athlete policies). And of course these rules and this debate impacts trans people who have no interest in sports because it serves to obfuscate and legitimize what is ultimately a "debate" about their very existence.

Another thing that didn’t make the cut on Tested is just how much money it costs to bring a case to CAS. On the CAS website, they say that “The ordinary procedure involves paying the relatively modest costs and fees of the arbitrators, calculated on the basis of a fixed scale of charges, plus a share of the costs of the CAS.” Filing a case costs 1,000 CHF, or about $1,154. There is then a table offered by CAS to calculate the cost of arbitration. This cost is evaluated before the athletes brings a claim, and athletes are expected to put down a deposit to cover that cost. All told, simply to bring a case to CAS can cost over $25,000. That number does not include the amount of money an athlete might be paying their own lawyers, which is an added expense.