TESTED EPISODE FIVE: UNFAIR ADVANTAGE?

Episode Five: Unfair Advantage?

A battle over science and ethics unfolds. World Athletics releases and then tweaks multiple policies impacting DSD athletes, while critics cry foul. In this episode, World Athletics doubles down on its claims, Caster Semenya challenges the rules again, and we dig deep on a big question: what constitutes an “unfair” advantage on the track?

→ → → LISTEN HERE (or wherever you get podcasts) ← ← ←

For each episode, we’ve published a full, annotated transcript with sources and further explanation for all the things we’re saying. You can find those here.

The Tested website also features a few other goodies, including this timeline of the entire 100+ year history of this topic.

BEHIND THE SCENES

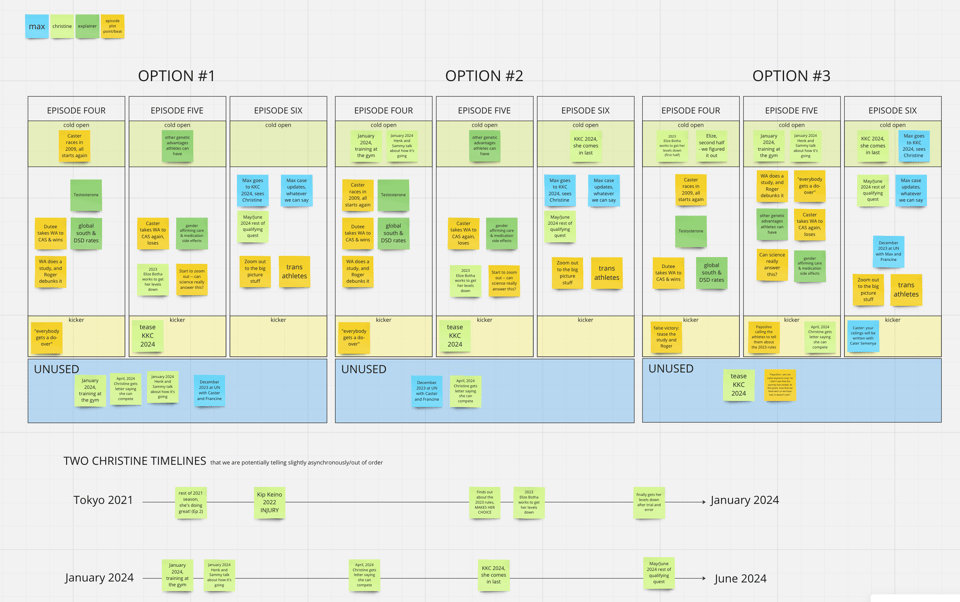

This series was, structurally, really hard to figure out. There is SO much history and stuff to potentially cover, and we only had six episodes. Plus, we were tracking two main threads: the modern athletes like Max and Christine, and the historical path that led us to this moment. Episodes four and five are where those two paths start to converge. But how do you pass that baton seamlessly? How do we not create timeline chaos by jumping around between different moments and eras?

This is the kind of thing that normally you’d solve by getting into a room together and deploying the whiteboard/post it notes. But our team was totally distributed, so we couldn’t do that. So instead, as we wrestled episodes four and five together, I built an online white board to work through the various options together.

We actually didn’t wind up, in the end, doing any of these options exactly. What you hear in the show is a different, fourth thing. But working through this as a group really did help figure out what to try.

ADDITIONAL MATERIAL

While I was in Namibia and Kenya I kept a running list of all the songs that the athletes were playing. I really love building playlists to commemorate reporting trips — little time capsules of what I heard, and enjoyed, on a trip. So here’s a playlist for you, full of songs that I heard and enjoyed.

On the show we talk a lot about so-called DSDs (differences of sex development). We didn’t have time to get into detail on specific diagnoses, and which ones fall under the various eras of regulation. But I wanted to make sure that resource was available so we had science journalist Joanna Thompson (herself an elite runner!) write us a handy guide to DSDs.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR: World Athletics, Unscripted

As you hear on the show, nobody from World Athletics was willing to speak with me on the record. Which meant that we had to do our best to represent their opinions accurately and fairly based on court documents, public press releases, off the record conversations with people close to World Athletics, and whatever else we could find.

It’s not unusual for World Athletics to decline interviews about this. They rarely speak with reporters on this topic, and certainly not with reporters they think are skeptical of their rules. Most of their communications are fairly buttoned up and on message. But there was one moment we found where a World Athletics representative spoke, off the cuff and live at an event. We were going to play some of this tape for you during the show, but we didn’t have space for it.

In 2019, Roger Pielke, Madeleine Pape, Andy Brown and Steve Maxwell did a presentation at a conference called “The Semenya case: What it means to athletes.” Their talk covered a lot of the same things we talk about on the show, and you can watch it online in two parts, here and here.

The thing that is different about this conference, however, is what happens at the end. When the panel opens up for the Q&A, a World Athletics lawyer named Frédérique Reynertz stood up and took the mic. She began with more of a comment, than a question:

Good evening. I have to say that I am biased to. I am the IAAF director of legal. My question — as you said it has to be a question rather than remarks — is that, so far, I think I haven't heard anything about what he actually means to athletes, tonight. I've, I've heard a lot about a very one sided position. And I wonder why the organizers have not invited a more diverse panel to be able to explain more, and give, more open, positions. I was sitting there with you throughout the entire week during the Semenya hearing, and I could spend at least 35 minutes, correcting inaccuracies and blatant lies that were exposed tonight. And I think it's a pity for the audience that, you haven't given them the opportunity to hear, conflicting views and maybe a more open way of presenting things.

The panel responds to this by saying that the IAAF was invited to be on the panel, and they declined. Reynertz says that that is untrue.

Roger Pielke then says “Let's have a discussion. If you're accusing us of lying, then let's. We have a few minutes. So let's hear your best one.”

Things devolve from there. Reynertz seems to argue that the rules are not actually racist because the first athlete who challenged them was Indian, not Black. Her and Pielke then get into a heated back and forth about whether the IAAF can release data for analysis or not. Reynertz at one point claims that Pielke’s reanalysis of the data was never published in a peer reviewed journal — he counters with the fact that it certainly was. The whole thing is tense. It starts at 25:30 here, if you want to watch it.

I’m struck by this particular footage because it really is one of the very, very few times where a IAAF representative is speaking seemingly off the cuff. Reynertz has her talking points written out (in fact, people who were there told me that she circulated a printout of them to the attendees of the conference, and the IAAF published them online here) but she’s also having to reply and respond to a more live debate. And, at least in my opinion, she doesn’t seem entirely prepared to do so.

We didn’t use this audio in the show, because we couldn’t quite find a place for it that didn’t require a whole bunch of setup.

CUTTING ROOM FLOOR: The Blade Runner

At one point in writing this series, I thought about including a section about the true origin story of my obsession with this story.

I didn’t follow the Caster Semenya story closely when broke in 2009. It wasn’t until 2012, when I was an intern at Scientific American, that I came across this question in the course of reporting a story about a completely different South African athlete accused of a very different kind of unfair advantage.

At the time, Oscar Pistorius was making headlines for being the “fastest man on no legs.” (He is now, unfortunately, probably more famous for being convicted of murdering his girlfriend in 2015.) Pistorius was born with a congenital issue called fibular hemimelia, and at 11 months old had to have both of his legs amputated about halfway between his knees and ankles. As a kid, Pistorius played rugby, but after a knee injury he turned to running. His specialized blade prostheses were not only eye catching, but very effective, and in 2007 he set a world record for disabled runners in the 400.

By 2007, Pistorius was running times that rivaled people with two full, fleshy, biological legs. And he decided that he didn’t want to race in the disabled category, if he could race able bodied people, and maybe win, he wanted to do it. And for a while, he was allowed. He started getting invited to races in Italy — one of our guests, bioethicist Sylvia Camporesi, actually joined the crowd to see him race.

But when Pistorius petitioned to run in the able bodied Olympics in Beijing, the IAAF said no. In fact, some people argued that he shouldn’t be allowed to run against able bodied athletes at all, because his prosthetic legs gave him an unfair advantage against able bodied runners. They argued that because his prosthetics are so light, he was able to swing his leg from back to front faster than someone with a heavier meat and bone leg, and thus have a faster turnover time than any able bodied athlete could achieve.

The thing is, that it’s really hard to prove that one person does or doesn’t have an unfair advantage. There are a lot of factors at play — in the science world you’d call this an n of one, where you just have on individual, rather than a large dataset or a big group you can analyze. When you just have one person, one datapoint, you can’t control for… anything. Height, weight, diet, genetics, training regimen, none of it. I wrote a story about this debate for Scientific American.

It was in researching this piece, that I came across Caster Semenya’s story again. Semenya and Pistorius have some things in common — they’re both South African, both track and field stars, and both accused of having an unfair advantage. But the coverage of the two couldn’t have been more different. Camporesi has written about the ways in which these two athletes were treated so differently:

Pistorius was a handsome white male athlete who had overcome many misfortunes, including congenital malformation of leg bones that led to amputation, and the early loss of his mother. He was portrayed as a role model for the disabled and an inspiration to many more, and it’s no surprise that CAS overruled the lower body, erring on the side of inclusivity.

Pistorius took the IAAF to court, that very same Court of Arbitration for Sport that you’ve heard about on this show, bringing his own experts to the arbitrators. And after a two day hearing CAS ruled in his favor, arguing that the IAAF could not exclude him from competition against able bodied runners.

The differences between these two cases also show up in the CAS hearings. In Oscar Pistorius’s case, CAS held the position that the IAAF has to prove, without a doubt, that Pistorius had an advantage. In other words, the assumption going in was that he did not, and it was up to the IAAF to prove that he did. But in Caster’s case, that did not seem to be the starting position. Camporesi has pointed out that in the Caster trial, the burden of proof was placed on Caster, not on IAAF. “In the end, CAS gave Pistorius permission to compete in the Olympics by shifting the burden of proof from the athlete to regulators, who where unable to show sufficient evidence of unfair advantage. No such dispensation was granted to Semenya, a black lesbian runner who pushed against Western ideas of the female norm. In her case, the burden of disproving unfair advantage remained with the athlete, setting her up for a worse outcome in court.”

This is one of the oddities of CAS. Because it’s not a true legal body, precedent doesn’t matter nearly as much as it does in a more traditional court. Each case is meant to be considered as a one-off, applying only to the specific athlete in question. When Caster lost the case, for example, they specifically noted that her case was only about her, not about the rules generally. “The arbitration here was only about athletics and it's about only, for the moment, Miss Semenya,” said Matthew Reeb, CAS Secretary, when announcing the ruling. “It may well be that when the DSD regulations of IAAF will be in force, that other athletes may want to challenge these rules because of their own specific biological profile.”

But of course in practice that’s not what happens — World Athletics uses the ruling as an endorsement of the rules writ large.

We, obviously, didn’t get into any of this on the show! There simply wasn’t time.

If you still want MORE of me talking about this, I’ve got you covered:

I joined It’s Been a Minute to talk about the Olympics.

I was on KQED Forum talking about the podcast, and taking live listener calls!

I’ve been making little social videos (lol send help) on Instagram and TikTok. If you’re wondering how fast (slow) I can run a 100, get thee to TikTok.

Next time on TESTED: The final episode! Christine and Max are some of the most recent female athletes in this century-long history to face tests, stigma, and restrictions. But they are unlikely to be the last. In this episode, we find out whether Christine qualifies for the Paris Olympics, as well as the fate of Max’s court case. And we explore the broader implications of the sex binary in sports. Is there a better way for sports to be categorized?