Who are we, and what might we become? What to read next.

Fiction and nonfiction asking the big questions.

Hallo, readers!

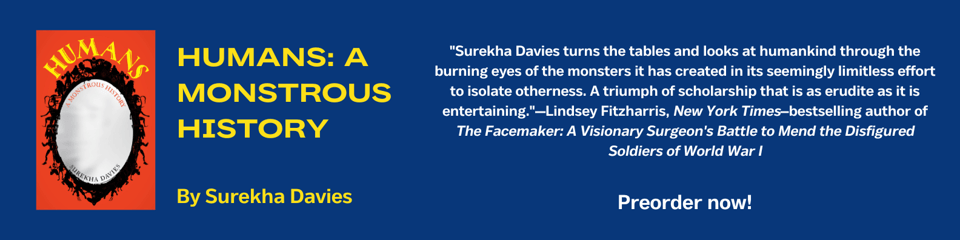

This newsletter comes to you from Paris, where I’m spending the week hoovering up some book and manuscript treasures to shovel into Humans, visiting museums in order to mull over my next book idea, and brainstorming with author and scholar buddies. I hope to share some Paris recommendations in future newsletters. Meanwhile, here’s what I’ve been reading.

Takes and recs: a novel set in the literary world

After a recent trip to Washington, D.C., I began reading Rebecca F. Kuang’s Yellowface. The novel is mostly set in D.C., a city I’ve long adored as an occasional stomping-ground, and where I used to live. I inhaled the book in a few days.

This is the story of a young white writer who steals a draft novel from her infinitely more successful frenemy, an Asian American, after witnessing her accidental death by pancake. From its devastatingly accurate capture of the feelings of a writer scrolling social media to its climax on the Exorcist steps in Georgetown, the book is a funny, unsettling, gorgeous romp through the mind and misadventures of an author whose life has become the farce of an episode of Frasier blended with the tension and duplicity of The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Yellowface poses questions that every writer asks: how is it that some people achieve success very quickly, while others languish in poverty and obscurity forever? How much do success and failure depend on factors besides the quality of someone’s prose or the power of their stories? On things they can’t change about who they are or where they’re from? On their less-than-fancy credentials or affiliations, data points that those with the power to ink book deals and movie options might weaponize against authors like they are plague diagnoses or felony convictions?

Perhaps most profoundly, Kuang invites writers to wonder: what kind of person will I choose to become at every step along my writing journey? And what stories will I tell myself about how and why I made those choices?

While there are villains aplenty in Yellowface, more than one of them has a legitimate grievance. The Hunger Games element of the literary world gives some of the villains a kernel of virtue around which to re-frame their villainy. The verdict? This is a delicious literary thriller with teeth.

Takes and recs: history of science

Human-animal hybrids, anyone?

Historians of eighteenth-century Europe have traditionally called this century the Age of Enlightenment. But as historian William Max Nelson IV shows in Enlightenment Biopolitics: A History of Race, Eugenics, and the Making of Citizens, French Enlightenment thought on rights, liberty, and equality emerged out of an underbelly of biopolitical assumptions that also gave rise to eugenicist ideas. I reviewed Enlightenment Biopolitics for Science, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Nelson carefully analyzes a wheelbarrow’s worth of unsettling eighteenth-century theories. The most jaw-dropping proposal was one from Abbé Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès. In the second half of the eighteenth century, the philosophe mused on the need to ease tensions between educated, politically active French citizens and their working-class compatriots engaged in manual labour, who lacked the education and opportunities to participate actively in the political sphere.

Sieyès suggested that humans be cross-bred with various apes and monkeys in order to create species of “anthropomorphic monkeys” to enslave, species with “fewer needs” whose members would “be less apt to excite human compassion.”

There’s a timely warning here. As I say in my review, “in a new age of proposals promising to reconfigure people by blending them with machines, scientists, policy-makers, and the public would do well to consider what lessons and warnings the intertwined histories of biopolitics and eugenics have to offer.”

Add a comment: