Walter Ralegh's headless monsters and annotation as thinking

On writing and picturing as forms of thinking and knowledge-making, with examples of Renaissance mapmakers and publishers demonstrating exactly this in the curious case of the headless men and the Amazons of Guiana.

Thanks for reading my free newsletter! If you’d like to support my work, buying or gifting HUMANS: A MONSTROUS HISTORY would be wonderful. Excellent free ways to support me include: borrowing HUMANS from your library or recommending they buy it; reviewing the book on, say, Goodreads, Amazon, or Storygraph (the links take you to the Humans review pages); adding it to your wish list or TBR list; or telling friends, family, colleagues, or students about it.

Hallo everyone!

Last week an article in Scientific American had me cheering: “Writing in Your Books Is Good for Your Brain - Here’s Why.” Videos of immaculately annotated books and their annotators have been taking off on social media. Reporter Brianne Kane observes that this trend has people wondering whether writing in books is a bad habit or a helpful one.

For my fellow annotators, there’s good news: annotating helps people understand and remember what they read.

The practice of annotating books is as old as books, scrolls, and tablets. Medieval marginalia are famous for depicting pointing hands or manicules (little hands) and (sometimes rude) scenes of monks, knights, princesses, and monsters, a topic for a future newsletter.

When handwriting, ownership, and other clues allow scholars to identify a specific person as the annotator, their marginalia help piece together how they read and made sense of the world through their reading.

I used to be a curator at The British Library, one of those places with reading rooms into which you’re not allowed to carry anything more alarming than a pencil.

No pens! No correction fluid! And definitely no highlighters!

So imagine the horror and excitement of sitting in the Biblioteca Marciana in Venice, a magnificent Renaissance library a mere javelin’s throw from the Basilica San Marco, with centuries-old manuscripts on my desk, when the director offered me an egg.

It was the week after Easter, years ago. The director had a twinkle in their eye. And they gave everyone in the reading room a chocolate Easter egg wrapped in shiny paper.

The safest thing to do was clearly to EAT THE EGG, right there in front of the manuscripts. For this former curator who still twitches at the sight of anything stronger than a pencil in a library, this felt both wicked and awesome. Once a curator, always a curator, right?

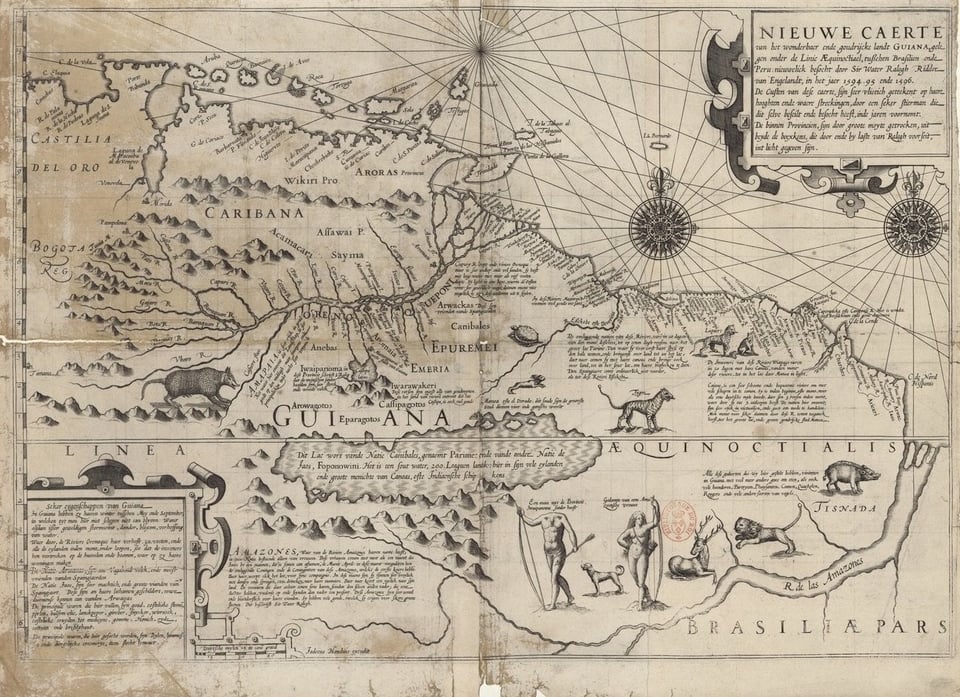

Back to Writing In Things. One of the in-house famous items in the British Library Map Library is a battered (not by me) exemplar of Amsterdam mapmaker Jodocus Hondius the Elder’s map of Guiana circa 1599. The centre sports an ordinary-looking dog and deer, an elegant Amazon posing with her gigantic bow, and a chap with his face in his chest allegedly from the province of Ewaipanoma.

The best image I have of the whole map is of the one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (zoom in online here):

The British Library’s example contains manuscript annotations in a seventeenth-century Dutch hand. Here’s a detail:

To the right of the Amazon is the curt “thus Ralegh” (“sic[u]t Ralegh”) in Latin. Below the headless figure is an annotation in Dutch: “This I think it fabricated because no Dutchman ever saw it.”1

(I received this image years ago and the lower inscription is cropped, alas, but you can get a sense of the bottom line of the longer inscription here.)

A lot is striking here. First, there’s the avowed reason behind this reader’s skepticism: none of his countryfolk had encountered an Ewaipanoma. There wasn’t anything intrinsically incredible about headless people at the distant reaches of the earth where the climate was extremely harsh - in, for example, equatorial Amazonia.

Climatological thinking was common at a time when people thought human bodies and minds were not fixed, but squishy. As I wrote in my new book, Humans: A Monstrous History, and in a short essay published last week in Pasts Imperfect, this was a tradition stretching back to classical antiquity.

The other half of the story is less hilarious. The Dutch annotator seems to have known that no Dutch travel accounts had described a headless tribe in the Amazon. Sir Walter Ralegh had first proclaimed their existence in his The Discoverie of the Large, Rich and Bewtifvl Empyre of Guiana (London, 1596). The annotator of the British Library’s copy of Hondius’s map of Guiana considered their own countryfolk reliable purely because they were their own countryfolk - a bit of parochial prejudice, all too widespread in the world today and that continues to shape knee-jerk reactions to the testimony of people framed as outsiders.

Around 1598 the earliest surviving images of Guiana’s Amazons and Ewaipanoma appeared on two of Hondius the Elder’s maps and on the title-page of a Dutch edition of Ralegh’s Discoverie from the Amsterdam printing-house of one Cornelis Claesz. These works and more feature in the Guiana chapter (chapter 6, ‘The epistemology of wonder: Amazons, headless men and mapping Guiana’) of my first book, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters.

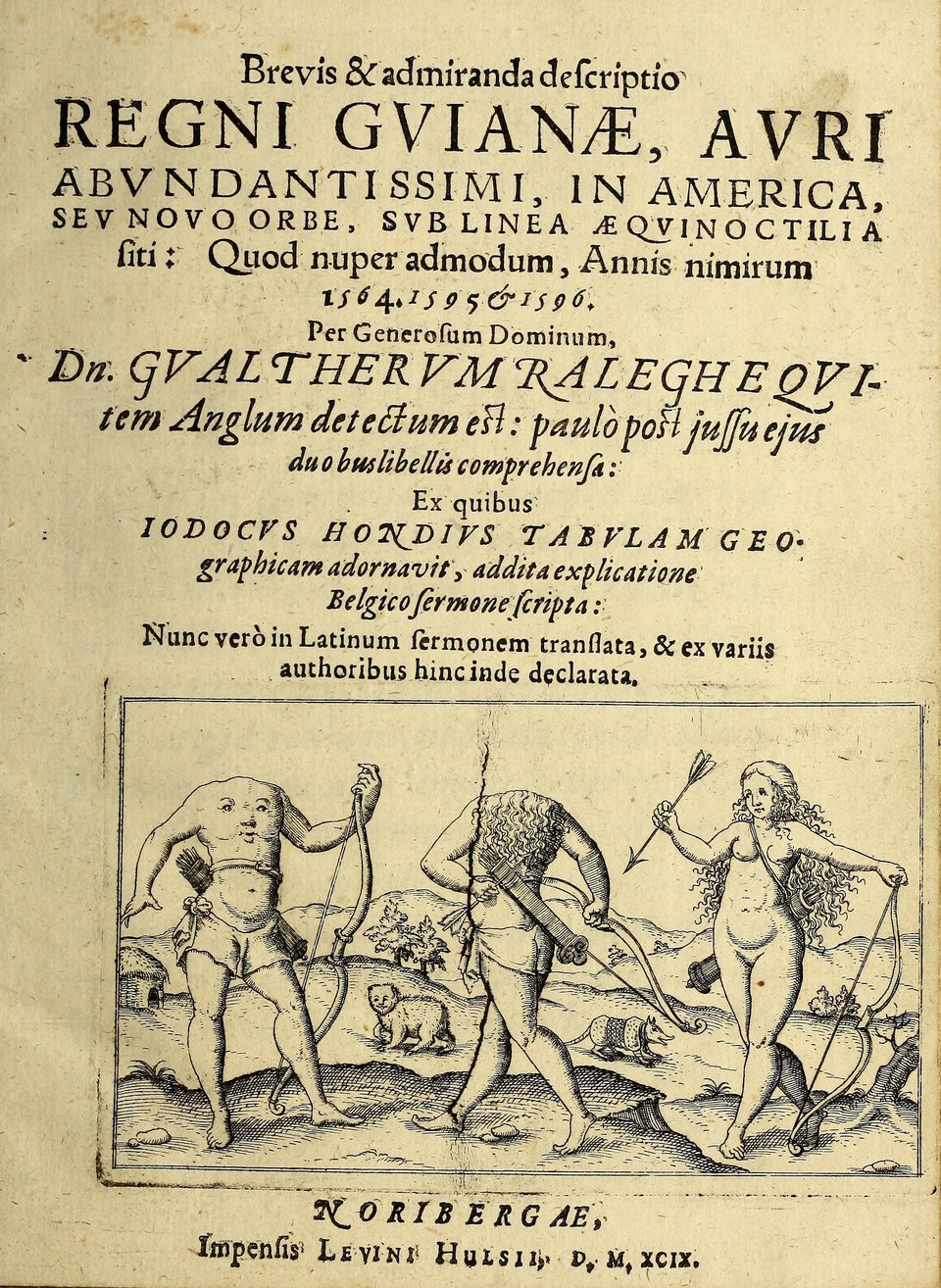

Let’s zoom forwards to the striking and heavily abridged Latin and German spinoffs of Ralegh’s Discoverie of Guiana that tumbled off the presses of the Nuremberg publisher Levinus Hulsius in 1599.

This pamphlet includes notes on the province of Ewaipanoma and observes that Ralegh had described a tribe of headless people who supposedly lived there. Hulsius cites a map by Jodocus Hondius the Elder as the source for this information. He describes the province’s people in the manner of Ralegh’s text, but adds a moral judgement absent in Ralegh’s text:

“…a race of men, without a neck or heads, bearing eyes and the remaining parts of their face in their chest, who nevertheless are otherwise strong, loathsome, and barbarous men.”2

The most eyebrow-raising extrapolation, however, is visual. Check out the book’s title-page:

The Ewaipanoma and the Amazon at left and right are similar enough to the figures on Hondius’s and Claesz’s maps and travel narratives to have been inspired by them.

The person at the centre is a hybrid of the Ewaipanoma and the Amazon. Pictured from behind, they sport a magnificent head of hair: an imagined mirror image of the Amazon’s flowing tresses.

And yet the hybrid has no head.

Enter the headless Ewaipanoma.

Could these three figures be related?

In his Discoverie of Guiana Ralegh wrote that (like their classical counterparts) Guiana’s Amazons were a tribe of women without men, who spent a month every year with the men of a nearby tribe. The Amazons apparently kept any girl children who sprang from their liaisons and gave away the boys. For a seventeenth-century viewer peering it would appear that it was with the headless Ewaipanoma that the Amazons conceived their children.

By suggesting that folks with heads and folks without could have children together, the designer of Hulsius’s title-page challenged assumptions about the boundary between monstrous and regular nations. The standardized features of all three figures, like their elegant postures, domesticate the extraordinary.

This sense is reinforced by a fold-out plate inside the volume and makes the wondrous Ewaipanoma seem more plausible.

The plate faces the start of Chapter VI, which begins with a brief description of the Ewaipanoma, typeset in italics. This is followed by several paragraphs in a smaller, regular font. These comprise excerpts from ancient and medieval authorities like Pliny the Elder and Isidore of Seville who described headless people: seemingly corroborating evidence.

Each chapter of Hulsius’s digest of Ralegh’s Discoverie of Guiana unfolds this way: some text summarizing an aspect of Ralegh’s narrative followed by excerpts from earlier, authoritative writers on the general theme. This is how the Amazons appear in Hulsius’s Ralegh spinoff, too.

The structure of this pamphlet invites readers to make up their own minds about Ralegh’s tales. At the same time, the visual imagery designed for it makes the alleged monstrous peoples of Guiana more believable.

For Hulsius, the Ewaipanoma lay just within the limits of credibility. He packaged his pamphlet to argue that case. As I discuss at length in Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human, early modern ethnographic credibility was a moving target. And the practice of reading, note-taking, thinking, drawing, and writing can generate unexpected solutions to mysteries that are (for the reader) too difficult to test empirically.

One reason I love buying hard-copy books is to be able to hand-write in them, a practice that helps me to understand what I read. Another reason is the SHINY, SHINY hit of holding a new physical object in my hands. The best time to start reading a book, even for a few minutes, is the moment I first hold it. It makes a book’s contents and their promise memorable - handy when they later become exactly what I need to be reading for a task at hand.

And it means I’m often recommending books I’m a couple of chapters through because I capitalized on the SHINY, SHINY moment and imprinted them onto my brain.

What happens when you don’t annotate books, or take handwritten notes elsewhere, or take notes in any form? You’ll have far less of a sense of what your brain can do, and what’s even in your brain.

In the words of educational psychologist Maryanne Wolf, who Keane quotes in Scientific American, reading deeply enables us to “go beyond the wisdom of the author to discover our own”, and the practice of annotating facilitates deep reading.

The Nuremberg printer Hulsius may have gotten things wrong, but his process was sound.

The way I think about it, each human brain is an enchanted treasure chest containing an entire galaxy. No one knows the full extent of what’s in there because there’s so much in there, and because it keeps multiplying in response to the world around it and its own thoughts and deeds.

What’s in your brain and what it shares with your consciousness depends on what you ask it, what time of day it is, and even your mood (Coffee! Fatigue! Fear! Optimism! Microbiome!). The brain is the ultimate other dimension of science fiction. And each of us has a unique one: a Schrödinger’s brain.

(By what’s ‘in’ a brain I’m referring to all the facts, insights, words, pictures, sounds, and feelings that a brain may have, turn into thoughts, and potentially share with the world.)

A couple of years ago a nasty billionaire wondered on a social media app I no longer use why anyone bothered writing, much less reading, books. According to him, a book could be summarized in a handful of sentences, and that was all anyone ever needed. I don’t remember whether this spurt of nonsense was part of a larger screed about how people should just feed copyrighted work into plagiarism-ecocide machines (my newsletter on them is here) and prompt them to provide summaries in bullet-points or not, but you get the picture.

If this were true, reading the back cover of a book should provide no fewer insights or transformative effects than reading the actual book, a statement that all of us reading these words know is patently untrue.

Spend time reading a book and you’ll have thoughts and feelings you didn’t have when reading the back cover summary. Spend time reading a book - whether it’s a few pages or the whole thing - and your brain will start having thoughts of its own sparked not just by the facts or story on the page but also by how those things activated your own memories, knowledge, values, assumptions, needs, goals, and temperament.

No two people would summarize a book the same way. Heck, the same person, years apart, reading a book for with different goals and experiences, would summarize a book differently.

This difference is even greater when it comes to annotations. The notes I make in the margins of books today are shaped by why I’m writing in those books at this moment - the questions I may have brought to the table.

Spend time reading and reading changes you. Make words, pictures, or dance moves to flesh out your thoughts as you read, and those changes are greater - and you make something unique.

Every time I write this newsletter I’m struck by what my brain does. It’s always something I didn’t entirely plan when I started writing. I thought this newsletter was going to be about medieval and Renaissance annotated books, my favourite manuscript annotation of all time, and the neuroscience of learning. What my brain added from its treasure chest was the science fiction analogy, the comparison between writing as an active mode of thinking by making and doing (via handwritten words, keyboard, voice notes, picturing, dancing), the story of my visit to the Biblioteca Marciana, and the exhortation to value each one of our brains.

It’s also striking how I might sit down to start a newsletter issue feeling a bit apprehensive - what if everyone HATES this issue?! - and yet get over that feeling. Once my fingers have been moving for a few minutes, the galactic treasure chest condescends to open and to issue something that feels new to me, and the stage-fright is over. I’m too busy rummaging in the chest before I become too tired to prop it open with my feet while dangling down to reach the gems.

New writing

A new essay is out in the world, and you can access it for free: “Ancient Typology and Monstrosity in the Shaping of Racial Hierarchies”, Pasts Imperfect, September 25, 2025.

ICYMI, "“Resistance is futile.” Why Star Trek: TNG’s Borg Collective Is the Perfect Monster for Our Time" in Reactor Magazine, Sept 24, 2025.

Upcoming event

Sat Oct 18, 9-11am ET / 2-4pm UK. Monster Lab - online; get tickets here.

Related newsletters

Interested in more newsletters on writing and making things? I wrote one that blends music, lemurs, and managing the creative brain. Another is about how so-called gen AI is the antithesis of qualitative research and history writing.

Feel free to share these and other newsletters with your friends, relatives, students, or colleagues - and to let me know how they respond!

“sic[u]t ralegh”; “Dit meen ick, is versiert mits noyt gene hollander gevonden.” Transcribed, translated and in Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge University Press, 2016), at pp. 197-203. ↩

Levinus Hulsius, Descriptio regni Guianae … (Nuremberg, 1599), Cap. VI, 11. For a longer quotation, the original Latin, and a much longer discussion, check out my Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 209-214. Digitized versions of the John Carter Brown Library’s copies of Hulsius’s pamphlets are available on archive.org. The quoted page in the Latin version is here. ↩

Add a comment: