The Craft behind HUMANS: A Monstrous History

In which I expand on last week's presentation at the American Historical Association Annual Meeting, and ask readers what they'd like me to write about in the coming year.

Happy New Year, readers!

I spent last week at the American Historical Association Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, PA, USA. I had co-organized two roundtables, The Historian as Storyteller, with Tamara J. Walker (Barnard College, Columbia University). The roundtable abstracts and some anticipatory thoughts were in my last newsletter (in your Inbox or on my Substack).

Below is an expanded version of my presentation. My assignment: to talk about how writerly techniques and thoughtful structuring of a text could help craft accessible yet thought-provoking narratives.

I focused on four topics: categories of analysis, content choice, structure, and ethics.

Attending to the craft of storytelling helps to illuminate stories, arguments, and forms of evidence that transcend academic orthodoxies of period, geography, field, and discipline in ways that enrich both general and academic readers.

Reader assignment: I’d love to know what you’d like to read from me this year! This newsletter ends with some questions about that.

My AHA presentation

(Expanded version of a presentation delivered on Saturday January 7.)

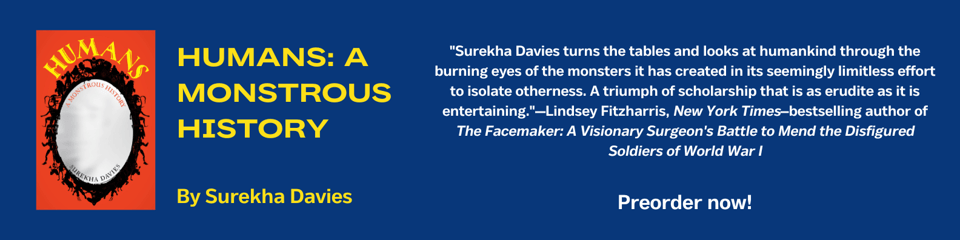

I’m going to introduce Humans: A Monstrous History, my current book project (full manuscript under review), and then talk about how I engage four elements of storycraft: categories of analysis, narrative structure, content choice, and ethics.

The elevator pitch

Humans: A Monstrous History tells a transregional history from antiquity to the present, a history of people’s attempts to understand themselves and the world through who and what they thought broke the category of the human. It reveals how people have categorized beings in and beyond the world, perceived otherness, and sought to control those who challenged social orders.

Through this narrative I show how today’s troubling divisions and urgent questions about nature, society, and technology are built on age-old anxieties, now called by other names. The result is a history of humanity through monsters and monster-making: ideas, theories, and actions people took around what they saw to be category-disrupting beings and communities.

Ideas about ecology, the human-animal boundary, race, gender, bodies, faith, the supernatural, machines, and extra-terrestrials have long rested on a foundation of monsters.

By imagining and identifying monsters, people created ways of thinking that persist today far beyond the realms in which the word “monster” appears. At stake in fears about monsters is our own humanity.

Persistent questions include: how can we identify monsters? Under what conditions might we become monsters, too? If a human becomes a monster, could they ever change back? And can those we identify as monstrous ever turn normal?

Putting monsters at the centre of a history of humanity reveals previously unnoticed aspects of how deep fears about boundaries between types of people/beings have shaped, and continue to shape, how people live in the world. My examples range from giants to robots, from witches to zombies, and from arenas ranging from politics to music.

Categories of analysis

The monster is a category of analysis, so categories are the central subject of Humans!

What do I mean by monster?

There are no monsters, and all of them are real.

I trace monster-making and category-breakers – beings called, in their own time, monsters, creoles, hybrids, barbarians, shapeshifters, aliens, and so on. No category stays the same over time – not religion, science, or empire – and not monsters.

Monsters are portals from central, urgent, originary questions in one field of inquiry to those in another.

Monsters are the work of the imagination. The term is a catch-all for positive, negative, and neutral concepts with which people refer to someone or something that falls outside the categories of their classification systems.

Humans uses examples of monsters and monster-making as lenses to refract into view hidden assumptions about beings that exist in the universe. People think with real and imagined monsters in order to define the parameters of the human.

The field of Monster Studies goes back decades in the study of culture, particularly in European literature, Film Studies, and related fields, but also in premodern art history, history of science, and the history of religion, among others.

When I started thinking about this book idea it was a history of monsters in European culture from antiquity to Frankenstein. Over time, however, it became apparent that the most original and most valuable version of this book that I could write would go from antiquity to the present, to include examples of monster-making from around the world, and to get outside of not only European studies but also Monster Studies.

What I mean by that is…. Monsters are not necessarily universal. If your ontological schema is a continuum, there would be no monsters.

More inclusive, continuum-based ways of engaging the world – of not seeing fixed boundaries between beings or being able to cope (hostility or without meltdowns) with beings who change from one type to another – might offer lessons for the present and the future.

Thus, Humans speaks back to rigid classification systems that police boundaries and turn individuals and groups into problematic outsiders. The book does this by attending not only to contexts where monsters were seen as threats or errors, but also to places and times in which category volatility or category continuity were seen as just part of how things were.

I engage but also step beyond today’s Western categories of monster. Humans is as much a book about observing, interpreting, and organizing beings in the world (visible and invisible) as it is about “monsters” (whatever they are).

Structure

Humans has an unusual structure for a trade-list book covering several millennia. Rather than a single chronological arc running from the start to the end of the book, each chapter runs from early examples up to the present day.

The overarching structure is not chronological but ontological. Nine chapters start with the earth, then examine how cultures have thought about boundaries between human and animal (or the lack thereof), then move to forms of categorizing humanity, and then on to beings beyond the visible realm, then machines, and finally extra-terrestrials.

Even within chapters, the first order of structuring is not necessarily chronological. Rather, I follow the lead of various monster mysteries that build narrative tension (no spoilers; you’ll have to wait a while for more!).

Content choice

This book contains two interwoven narratives. One narrative charts the origins and trajectories of Afro-Eurasian monster-making traditions carried in ocean-faring ships sailing under European flags and their entanglement with cultures and monster-making practices around the world.

The other narrative introduces readers to category-breakers in Africa, Asia, the Americas, and the Pacific world. This interweaving reveals something about the deep structures of the present.

Global international organizations of the past century were often built on foundations of ancient European world-views, insofar as those with the most power at the table were often Western imperial nations.

Some chapters hew more closely to the history of monsters in the West. Others tell broader stories that offer tools with which to address global problems created by Western monster-making. In that sense, this book is an alternative history of the West, one braided with a transregional philosophical essay on monster-making.

Popular literature on monsters is often all about weirdness. It tends to gaslight thought processes. The moment someone says “monster”, people usually think imaginary or superstition. They are then less likely to think of terms like science, knowledge, or classification.

This is where Humans steps in to expand the conversation, drawing on decades of scholarship in monster studies, history of science, and cultural history.

Ethics

What are the ethics of writing a book about three thousand years of human history when one doesn’t read all the world’s languages? Should I even be writing a book of this scope? But if not, then no one can ever write it, because no one will ever have all the languages, or all the expertise across millennia, whatever one means by “all”.

Bookstores contain plenty of general-interest books covering millennia and ranging around the world. Some are even written by people with deep historical training. Yet, to adapt the words of a 2022 movie title, no one is a specialist of “everything, everywhere, all at once”.

If I don’t write the truths that I have learned, and continue to learn, about the past, the present, and the future by thinking with monsters, I would be leaving (monster-shaped) gaps in the conversation.

Worse, I’d be leaving the field of big, broad books to writers who may have far fewer qualms than I do about writing expansive histories, who may not be looking to get outside of Western categories of analysis, and – certainly – to those who just don’t know as much as I do about why monsters matter.

So my answer to the “should I even be doing this?” question is this: as long as I am transparent about my methods and sources, as long as I am reading scholarship in a wide array of fields, periods, geographies, and scholarly traditions, by a diverse range of authors, and consulting as wide an array of sources as possible, I can bring myriad times, places, and forms of evidence together to tell new, illuminating stories that speak to my ethical and intellectual commitments.

There is a saying, “write what you know”. By proposing the category of the monster as a theme or a lens as significant as politics, economics, gender, empire, or faith, I’m doing exactly that.

Questions for my readers

Do you love reading – or writing – history books aimed at the general reader? Are there books whose unusual structure or organization help them to tell new stories that keep you glued to the page? I’d love to hear about them.

Do narrative history books ever re-tread their chronology multiple times – that is to say, have each chapter go back to the beginning and treat the period again, as opposed to, say, concentrating on a different theme per chapter but moving through time only once? Do feel free to put thoughts and suggestions in the comments.

Next week I’ll return to my usual newsletter format, with book, art, music, and film notes alongside musings on what I’m writing, doing, and thinking. Over the coming weeks, you can expect thoughts on maps, monsters, habits for creative people, and my favourite books on the art, craft, and science of writing.

I’ll also write about how I navigated a zig-zagging path of opportunities and limits in my quest to make a living as a researcher and writer. If you have any requests for advice or for topics on which you’d like to hear from me, I’m all ears!

Add a comment: