Soldering irons and oscilloscopes: my brush with actual science

First, a news flash: On Thursday July 31 at 1pm US Eastern Time / 7pm Central European Time I’ll be on The Colin McEnroe Show, a live public radio show about culture, history, and science with an appetite for stuff that’s “eclectic, esoteric, eccentric.” Each hour-long episode typically hosts three guests in turn; I don’t yet know when in the episode I’ll be on. You can listen to the show live! There will be a podcast released afterwards, so you can subscribe to the show for free wherever you get your podcasts to receive it.

My brush with actual science - and what is history of science?

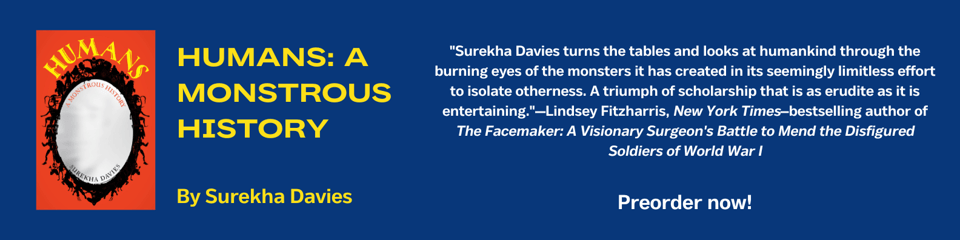

I’ve been preparing for an interview for a film and TV podcast by re-watching formative episodes of Star Trek. The origins of my latest book, Humans: A Monstrous History, lie in a youth spent watching Too Much Star Trek – if there is such a thing. When I began my BA at the University of Cambridge, I was planning to major in theoretical physics. It was all Captain Picard’s doing, helped along by Carl Sagan’s Cosmos. Who wouldn’t want to boldly go to distant star systems in the USS Enterprise, meet aliens, or travel at the speed of light, go back in time, and meet themselves?

But undergrad science didn’t feel like Star Trek. Physics lab sessions began with a trek on my little legs down a narrow country path lined with overgrown hedges and stinging things to reach the fabled Cavendish labs. There I duelled, with my bare hands, a workbench strewn with new-to-me and (frankly) low-tech instruments like soldering irons and oscilloscopes, followed assignment manuals ghost-written by sphinxes, and cajoled the passive-aggressive, eyebrow-raising lab assistants (ancient-to-me people a.k.a. grad students) for clues, all to run weekly experiments over an interminable four – and later eight – hours. These riddle-pocked quests never worked. And that wasn’t even the worst thing.

There were no starships. No nebulas. No ALIENS.

The quantum mechanics course was the last straw. There was no getting around it: there would be no warp drive in my lifetime. Cue mid-life crisis!

I wasn’t the only one in a mess like this. Multiple survivors of the Natural Sciences tripos, as Cambridge degrees are termed, ran away from one or other science that wasn’t what they had imagined. (The tripos is so named because candidates used to sit a verbal disputation exam on a three-legged stool – a tripod or tripos – designed for both alertness and accidents.) Many dreamers and “I hate labs” folx fled to history and philosophy of science.

My second-choice science career had already lost out in middle school. Too many Jacques Cousteau documentaries and a love of the Jaws movie (which I wrote about in a recent newsletter) meant the point of biology was to say, “Where’s the shark cage?”, not to cut up slimy things at another instrument-strewn work bench, this time bearing microscopes and scalpels.

Luckily the escape from physics to history and philosophy of science was a seamless option within my natural sciences degree. I became a historian of science who focused on European voyages of exploration across the Atlantic Ocean and European-Indigenous American encounters.

I was clearly attracted to anything that might give me the “strange and wondrous” fix that Star Trek provided. (Realizing how much of the history of discovery was about slavery, warfare, and dispossession would come later.) At the same time, what I chose to study was about as far away from the history of physics as you could possibly get. (If I never see a soldering iron or an oscilloscope again it will be too soon.)

Indeed, my interests as a historian of science were so “not what people think of as science” that when I began scoping out a PhD topic, I fell off the map of what then counted as history of science. Instead, I followed less typical sources like Renaissance explorers’ journals and map illustrations, and the questions they prompted me to ask, without any regard for what a “normal” history of science topic was supposed to be like.

Despite getting an M.Phil. in HPS from Cambridge I didn’t do my PhD in a history of science department in the end, but in an interdisciplinary Renaissance studies department at the University of London that let me hold off choosing a discipline. History of science seemed uninterested in the history of anthropology (broadly defined) of the period before the university discipline emerged in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Renaissance travel writing wasn’t a historical source type that was trendy in history of science the way it was in literature departments. History of science in the Anglophone world didn’t admit that Iberia had serious science in the sixteenth century, when Spain and Portugal had “big science” funded by the state and were hubs for fields like cartography and navigation. And the discipline wasn’t particularly interested in visual sources. All this has changed for the better although, IMO, those assumptions persist even though they are less pervasive.

I spent years thinking, “oh, I guess I’m actually a cultural historian, not a historian of science.” But by the time I’d finished the first draft of my first book, Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters, I realized that well, actually, I did have opinions about the history of science, and had things to say to people who called themselves historians of science.

By the time I wrote my latest book, Humans: A Monstrous History, I entirely owned history of science as the umbrella description for what I do: I just define the tent as WAAAAAY bigger than boundary-policers do.

Humans: A Monstrous History is a history of categories. Categories emerge when people draw lines in the sand and say, “here’s A Thing, here’s Another Thing, and anything lying on or across the boundary I just made up is weird stuff that doesn’t fit.” Dear reader, that “weird stuff” is the monsters. They are the category-breakers that show that the world is far more wondrous, malleable, interconnected, and full of possibilities than worldviews that declare that beings in the world are mean little shapes that are separate from one another would have us believe.

Podcast episodes: history of science, guys who sucked, and everything in between

If you’d like to learn more about Humans: A Monstrous History and my boomerang-style relationship with history of science, do check out the latest episode of the HPS Podcast, developed by the History and Philosophy of Science Program at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

Here are some more podcasts with interviews with me that will air soon – subscribe to the shows for free wherever you get your podcasts to make sure you’re notified when they drop:

This Guy Sucked is “for haters, by historians.” It’s a light-hearted and often hilarious podcast that only began this spring but already has a cult following. In each episode historian Dr. Claire Aubin chats with a guest about why a famous(ish) dead person sucked. Exactly how and why these folks sucked (or why the way they are remembered sucks) tells us something about them, their era, and why people tell sucky stories about the past. The historians interviewed here reveal more complete – and more interesting – ways to understand those people, their times, and our own time.

Not Just The Tudors is a wide-ranging history podcast with in-depth author interviews. It’s about far more than the Tudors – come here everything from Aztecs to Mughal India – but if you’re into British history or the history of the period 1400-1700 or so, there’s a lot here that’s right in your favourite nerd-out zone.

Add a comment: