Happy Birthday, JAWS!

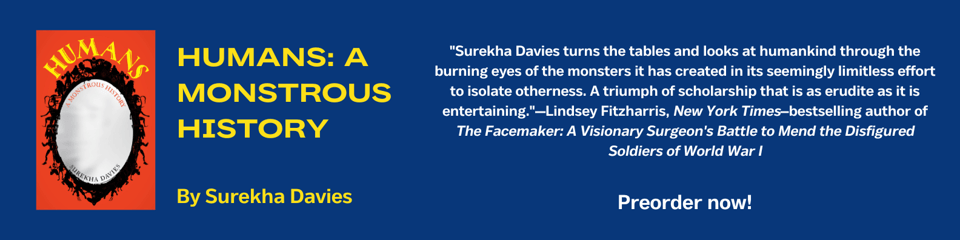

Thanks for reading my newsletter! You might also enjoy my new book, Humans: A Monstrous History, a history of humanity from antiquity to the present. I blend science, society, literature, and pop culture to show how and why people have invented monsters - category-breakers - to define the human in relation to everything from apes to space aliens. Videos, podcasts, book excerpts, and interviews are on my website.

Fifty years ago today, Jaws opened at the movies. With its suspenseful storyline, human drama, chillingly lifelike mechanical shark, and bone-chilling soundtrack, it’s a perfect thriller.

The storyline is classic disaster movie. There’s a deadly, mysterious, and then not-so-mysterious threat. The hero is an earnest professional (often a scientist, but in this case a neurotic police chief in a New England seaside town). The town’s politicians don’t take his warnings seriously, because to do so, they say, would hurt business (where have we heard this before?).

Most of the movie is about not seeing the shark, almost seeing the shark, or being frit out of our minds when we unexpectedly see the shark or its handiwork. The climax is A Big Fight Scene which ends in not saying - SPOILERZ!

Humans are puny creatures compared to a biblically proportioned shark or whale, and even punier compared to nature’s environmental giants, like hurricanes. In a 2017 documentary director Steven Spielberg described making Jaws as a nightmare. Art-making mimicked art.

Just as the story was a fight between nature and humanity by way of an apex predator proxy and three men on a boat, so was its making. There was much at stake for Spielberg professionally: this was his movie-directorial debut. Filming on the actual ocean - the logistics of willing light, tide, actors, and the hydraulics of lumbering fake sharks into a balletic drama rather than a TikTok misadventure of a Pamplona bull run in which the TikToker gets trampled - was its own Moby Dick.

(No, I have not seen such a TikTok. I made it up - the free association of an anarchic mind with “buy a tiny microphone and a selfie-tripod thing” on it. And no, I haven’t uploaded any TikToks yet but they’re swirling under the surface, like Bruce the shark and his two body doubles, but surely less horrible.)

I recently read Peter Benchley’s Jaws, the 1974 thriller behind the movie. I was amazed to find that there was even less shark in it. This is a tense book about human relationships in a disaffected suburban New England community that reminded me of the bored, dissolute characters in Donna Tartt’s A Secret History (a slow thriller set at a New England college).

We spend a lot of time in characters’ minds. Some story lines are completely absent from the movie (no spoilerz!). The movie’s shift of focus makes it a new story with different protagonists. Given the limits and possibilities of the screen and how hard it ended up being to get the mechanical sharks to do things - hence how infrequently we see The Shark, which is part of what makes the movie - the shift created an accidental goldmine for the studio and a breakthrough for Spielberg.

When I think about the movie now it is (of course) through the lens of monsters and monster-making. What do our sea monsters tell us about ourselves?

First we need to ask what our views of the sea reveal about ourselves. I recently watched Ocean, the latest David Attenborough-hosted documentary. I’m a long-time fan of sea monsters by which I mean wondrous creatures that grow my brain by revealing how multifarious and ingenious life is on earth. Not since March of the Penguins have I seen nature on a big screen, so this promised to be an absolute treat.

And it was. I’d forgotten to pack a notebook, so I pencilled notes in the gloom on the back pages of the book in my bag.

Excepting active volcanoes, the deep sea is perhaps the most hostile, most alien environment on earth for humans. In Attenborough’s words, it’s “dark, threatening and out of sight.”

But ocean depths also teem with life, just not life as we know it on land. As a few minutes of this documentary or a thrum through issues of National Geographic reveals, the ocean is full of monsters: creatures with tentacles, overly large heads, and their own light sources. Everything looks impossibly gorgeous or downright creepy.

As I show in Humans: A Monstrous History, monster stories define the parameters of the normal. They also often define normal anthropocentrically, and sometimes even in relation to the single individual doing the observing, inventing monsters by framing themselves as the only norm.

Our fascination with deep sea life of the sort that people run across halfway regularly (giant squid, not merpeople) stems partly from how inhospitable their home is to the likes of us. How different must they be to thrive there?

Since classical antiquity, extreme environments have been places deemed to produce monsters. Today, we simply place them at the edges of the universe, at the geographical limits of our instruments and sensory experience.

Despite the seabed’s relative inaccessibility, humanity has managed to depopulate large swathes of it. OCEAN contains apocalyptic footage from sea-bottom trawlers. These underwater tractors are such blunt instruments that the crews operating them throw away up to three-quarters of their catch. The seabed during trawling looks like a war-zone; afterwards, like a haunted, post-nuclear wastescape.

But we don’t have to do this. Prohibit fishing in swathes of the ocean, and they teem with fish pretty quickly. Those fish swim out of these no-take zones to regions where fishing is permitted. It seems both miraculous and obvious: in protected waters many more fish live long enough to spawn multiple times (if they are that sort of species), their habitats remain intact (more to eat and places to hide), and younglings have time grow larger.

The nature vs. humans undercurrent of everything from Jaws to climate-change denialism is a false binary. The question we should be asking is: What does abundance for all, for humans and the more-than-human world, really require?

The answer is simple. Us doing no harm. Just that. But no less.

More from me on strange and wondrous marine life

I wrote for Aeon Magazine about what black holes have in common with sea monsters back in the Plague Years.

And here’s a previous, whale issue of this newsletter about some marine things I visited in Edinburgh (Scotland) and New Bedford (MA, USA) and a great whale thriller-historical novel.

More sharks, oceans, and disaster movies

It’s the Week of Sharks on the Radio Lab podcast! I talked about sea monsters with one of their researchers, and was credited in the show notes for the first episode. Will a clip from our interview appear somewhere in the series? I haven’t noticed one yet - fingers crossed! - but if not, I know what to do with that mini-mike and selfie-stick.

For a cautionary tale of what happens when there aren’t enough guardrails around a billionaire’s ego (guardrails that include universal healthcare and free college tuition, so that fewer people are trapped working for megalomaniacs), watch the documentary of the OceanGate disaster, just out on Netflix. One dude’s ego-trip to do for underwater exploration what the owner of Space X was doing for space exploration (at time of writing, exploding vehicles) killed five people, including himself, and made life and work a nightmare for his staff. Left in his wake are bereaved families and shell-shocked former employees.

And if I’ve whetted your appetite for (reassuringly fictional) disaster movies, my fave is Dante’s Peak, the movie in which Pierce Brosnan and Linda Hamilton were born to star (fight me! :-) ). The threat here is a volcano, a portal to that other most inhabitable zone on earth: its magmatic core. Brosnan plays the scientist who turns out to have been right all along. The scenery is gorgeous. And, like Jaws, once you’ve watched it once, the captivating earworm of a soundtrack will be able to frit you out of your mind forever.

What else to read and watch

Nothing to do with sharks, but everything to do with how people tell stories about the parameters of the normal is historian of medicine Brandy Schillace’s The Intermediaries: A Weimar Story, a fast-paced, immersive, sometimes harrowing account of the research institute that performed some of the world’s first gender-affirming surgeries - in Berlin, in the years before the Nazis came to power - and the lives of people in and around it. That iconic book-burning imagery from 1933? That was of the library of the Institute of Sexual Science, founded by Magnus Hirschfeld. On Thursday June 26, at 7pm ET, Brandy Schillace will be talking live to Eric Garcia about the book on the amazing YouTube bookclub show, The Peculiar Book Club. Tune in live, or inhale the recording or the podcast afterwards!

ICYMI

I published an op-ed in the LA Times last weekend, about the history of monstrifying peoples for political purposes, and the monstrifying stories being told in the US today. More essays, interviews, and excerpts are here.

If you’ve read Humans: A Monstrous History, I’d love it if you would consider rating and reviewing it on Amazon, Goodreads, or Storygraph. Reviews can be as short as you like; even a word or a sentence. A higher number of reviews really helps with discoverability in a world of algorithms!

Add a comment: