Basement adventures showed me why ChatGPT can only ever be garbage.

Hallo readers,

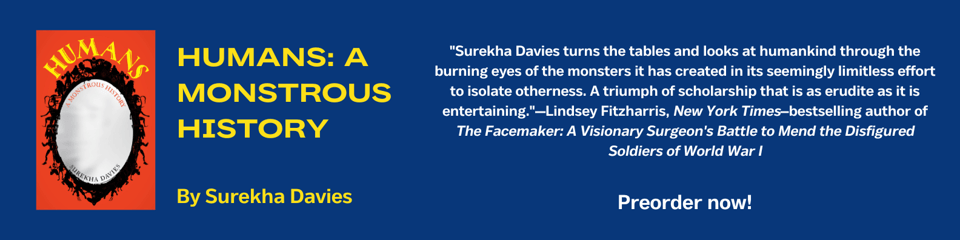

First, a news flash: Join me for a virtual book launch for HUMANS: A MONSTROUS HISTORY (published Feb 4) on Weds Feb 19th, 12:30pm EST / 5:30pm GMT! Click here for more info and to register for the event.

Speakers: Leah Redmond Chang, Ricardo Padrón, Caroline Dodds Pennock, Tamara J. Walker, and me.

Host: the Society for Renaissance Studies! (Thank you, SRS!)

For more events - virtual and in person - visit my book tour page at this link.

Pre-order HUMANS: A MONSTROUS HISTORY today! Click here for buying links.

Insights from (making myself go to) the basement

I began my PhD in 2002, at the start of the digital era of research: of digital cameras, remote storage devices you could put in your pocket, and most definitely laptops, although not smart phones. I was an early adopter of research tech though not of the recreational internet and its rabbit-holes, which seemed boring for the longest time. But it was always obvious that computers and software were just some tools among many.

My direct experience of historical sources and repositories would reveal things that I’d never figure out if I only used intermediaries. And the process of sitting with the sources - even in digitized form (if faithful and complete) and certainly with original artefacts - was what would help me say something new.

During the first four years of the PhD I worked half-time as a Curator in the The British Library Map Library.1 I was investigating images and descriptions of peoples of the Americas in European cartography, travel writing, and geographical works between 1492 and about 1650.

I wanted to understand how and why mapmakers devised and placed on their maps distinctive images and descriptions of peoples and societies in the Americas - images like Brazilian cannibals, Patagonian giants, and Mexican cities - and what that told us about the European experience of encountering (directly or on paper) peoples in what they called the New World.

The first order of business: see All The Maps. I searched The British Library map catalogue, then quaintly lodged in a CD-Rom. There were maybe 1,500 separate maps and atlases that covered the world, North or South America, or large swathes of the Americas, like Brazil, between the late fifteenth and the mid-seventeenth centuries. These maps would be my core body of evidence. To this I’d add maps and atlases that the BL didn’t have but that I could access via other key map libraries.

I didn’t want to order 1,500 things up to the Maps Reading Room, at the ordering limit of 15 items a day, only to send 90% of them back in seconds when they didn’t contain relevant stuff. I guessed that the Map Library staff would want to fetch those maps even less than I wanted to order them. So I negotiated clearance to go to the storage basement myself.

The British Library is four stories high above ground, but EIGHT stories deep below ground. There are four double-height basement levels. The Maps basement is in the deepest level. The basements are temperature-controlled on the cold side, for preservation reasons, although they aren’t as cold as the Folger Shakespeare Library basement (pre-2024 renovation) that a friend once called a meat locker.

Before anyone would let me down to the British Library basements, I had to declare that I could climb eight flights of stairs in five minutes. In other words, if there was an emergency drill, I’d be able to haul my ass out of Hades at speed.

Declaration complete, I headed to the library’s bowels for most of the day, a couple of days a week, for a month. I took with me the day’s printout of shelfmarks - sequences of items I was going to check that day. Most of the maps are stored in large, flat trays. I’d pull open a tray, take out its contents, stick them on a flat surface, and check whether they had writing or pictures of note. If they did, I recorded their shelfmarks. I’d order the items up to the reading room later, to study them.

Books and atlases are stored in what’s known as mobile shelving units: bookcases on runners, tightly crammed together. There’s a large wheel on the end of each bookcase. Turning the wheel moves the bookcase, which then bumps against the next bookcase; keep turning and multiple bookcases move out of the way. Thus batches of bookcases share a single walking space. By turning wheels, you can move a pair of bookcases apart to make a space wide enough to enter.

Does this sound dangerous yet? Because it kind of was. Drilled into me was the importance of taking in a kick-stool if I entered a shelving corridor. That would prevent shelves from closing in on me if someone turned a wheel without first checking to see whether anyone was in among the bookcases and I was too petrified to yell.

This experience was memorable, and not just because of the risk of being pancaked. Handling hundreds of maps in order to find the ones that contained content about peoples of the Americas had several advantages over depending on other sources - existing books and library catalogues - to tell me which ones they were.

First, almost no one in the 2000s seemed to think that images on sixteenth-century maps could be anything other than “decoration”, “propaganda” or, at best, evidence of nothing more than “copying” - another soul-crushing word that flattens human choices and decision-making, framing it as mindless. I can’t tell you how many curators, map dealers, map collectors, and map scholars said when they heard about my project, “oh, there isn’t anything to work on here, that’s just decoration”, or something similar.2

Had they done the work? Had they checked?! Nope. So why would I assume that the maps illustrated in existing books constituted the sum total of the maps that might be relevant for my research project?

In some ways, it was handy that I was working on world maps and maps of the Americas from the age of exploration. Many of these printed and manuscript maps and atlases were gorgeously illustrated, spectacular artefacts. There were many reproductions in large-format, encyclopedic tomes and in coffee-table books. But people who reproduced illustrated maps in their books because they contained what they thought of as “pretty pictures” that just made them more valuable weren’t necessarily interested in the writing on the maps. Sometimes I’d consult flashy map books that contained reproductions of maps but left out the map borders because they contained text, not illustrations. Yet that writing was a gold mine for me.

In the case of the famous-in-map-circles atlas by the sixteenth-century French cartographer Guillaume Le Testu, a magnificent volume housed in the Château de Vincennes on the outskirts of Paris, I read everything I could get my hands on. One of the former heads of the BL Map Library, Helen Wallis, had ordered black-and-white photographs of what appeared to be the whole atlas many years previously. I silently thanked her as I scanned the photos and zoomed in on my computer screen. And then I noticed a throwaway comment in an article. It mentioned that the atlas had text pages. What text pages?

There were no text pages in the photographs of the atlas. No other piece of writing about the atlas illustrated or even mentioned a text page. But it seemed as if there must be parts of the atlas that I had never seen reproduced anywhere.3

I went to Paris.

To cut a long story short (one with another basement), it turned out that each map in this incredible atlas had A PAGE OF TEXT to go with it.

As you can now tell, the only way I was going to know whether a map or atlas was going to be relevant for my project was by seeing it myself, or by requesting photography of the complete item. Stuff other people had gathered for their own purposes could only ever be a preliminary body of examples.

What about the British Library library catalogue? Hey, look, some of the catalogue entries say “ill.”, short for “illustration/s”. Hooray! I can just call those ones up and see if the images are relevant, right? I don’t need to go basement spelunking or ask nicely for all the maps to be brought to me, right?

Not so fast. Library catalogues, especially in a gigantic library like The British Library, are shapeshifters and multi-headed hydra. The BL has more than 150 million items, collected over centuries, assembled partly from earlier libraries bought or donated centuries ago. Such libraries are wonderful things…. But they don’t and can’t have entirely consistent catalogue records across their holdings.

Many of the British Library catalogue records in the 2000s had been written decades previously, perhaps even in the nineteenth century or earlier. When the computer catalogue came into being around 1975, the contents of a bunch of old printed and card catalogues were thrown on there with little editing.4

Dozens of different people would have catalogued those maps. They would have made different judgment calls about whether or not a map contained illustrations worthy of being immortalized with the word “ill.” And cataloguing conventions change over time.

There was no consistent rationale - there was no single mind - that had made judgment calls when recording the presence of illustrations. The basement would be full of maps that had illustrations, but that didn’t have “ill.” in the catalogue entry.

And I was also interested in textual descriptions on maps - sentences, paragraphs, commentary about the Americas. These were not something that catalogue records noted consistently. Here was another reason why I couldn’t assume that the trace of the thing that interested me could be mined from materials created for unrelated purposes.

I steadily compiled a short-list of British Library maps (and maps elsewhere) containing images or descriptions of peoples of the Americas. Along the way, I built a FileMaker database in which I kept track of the maps.

The fields were simple: title, author, date; a drop-down menu for region of production (French, Spanish, Portuguese, Netherlandish, Germanic, English; other); a drop-down menu to keep track of common motifs (giants, cannibalism, cities…); a check-box for printed or manuscript; a field where I listed books and articles that discussed the map; and some free-text fields.

I planned to attach a thumbnail of each map to each record. But once I’d seen each map, completed my database entry, taken quick notes, and transcribed captions and text blocks, the two hundred or so items were so clear in my brain that reading the author, title, and date was enough for me to remember which map it was.

Once I’d done this, it was easy to search for, say, all the Spanish maps that contained image of cannibals, sort them in ascending date order, and then analyze them in chronological order. I could quickly get a sense of how many among the 200 maps had a particular kind of imagery. The first draft of any chapter almost wrote itself.

I revised and re-wrote chapters MANY times. I consulted a lot of materials that weren’t maps, compared books and prints to the maps, and only then figured out what the maps meant. There were lots of rabbit-holes, many of them with cool treasure at the end (if you stepped carefully around the thistles along the way).

What does this archeology of a library, and of a grad student’s brain, reveal? How researchers do research. This is the anatomy of a research process. It’s how anyone interested in learning more about something, or in solving a historical mystery, has to think and make choices.

Scholars describe their rationale so that others can see how they got to their findings. Academic publications include sections where authors describe their source base and their rationale for how they approached it.

Historians often provide a sense of what doesn’t survive - maps that disappeared with the Lisbon earthquake of 1755, for example. What survives of the past isn’t a representative sample of what existed. Unlike a controlled scientific experiment in which (to an extent) a scientist might generate a representative, tightly-controlled snapshot of whatever they’re trying to examine, what survives of the past isn’t representative, and can’t be controlled. And so the kinds of stories we can uncover, the ways in which we have to think and work with and around the traces of these stories, and how we write up our findings, has to show that.

It is those acts of studying, analyzing, deciding, and selecting what is and isn’t relevant to the question that turns a mountain of amorphous material into a robust historical explanation. It is that process of showing where you found different pieces of your source material that allows peers and readers to judge whether or not there’s a good match between the questions you’re asking, the sources you examined, and the ways in which you examined them.

Fast-forward to the present, to the apocalyptical world of LLM-based generative AI.

If you ask gen AI to give you a draft, or “inspiration” (seriously?), or content, this is not what you get. Something without a brain scrabbled around and found stuff that looks like content but isn’t, because it wasn’t chosen, analyzed, and written by a person. Frankenstein’s monster copy-paste jobs from a bunch of different places? That’s not a summary. That’s word salad.

We abandon the body and what it learns by being in the world - the physical world - at our peril. By touching, looking, listening, smelling, and even tasting (undergrad geology and grownup gastronautery), we don’t just gather “data”, that soulless word that flattens everything that can’t be described in numbers. If we think about and feel what we experience by moving about in the world, if we mull and compare what resonates to our own knowledge and memories, if we analyze it using the perspectives and sensibilities gained from education and life experience, then what we have to say will be unique.

That’s what it takes to make something meaningful that doesn’t yet exist in the world. No one walks in the world in your shoes. No one can contribute precisely what you can figure out and say in just those words that are your voice. Those are things that the mysterious connection between your brain, memories, and the world might bring into being.

By “no one” I don’t just mean any other person. I also mean no one as in certainly not the ecocide-plagiarism machines popularly called generative AI, digital vultures bloated on stolen books which they churn together and vomit out in imitations of words from actual thinking, feeling brains. Yet AI boosters earnestly insist that taking all the colours in the paintbox, mixing them together, and throwing them on a canvas creates art, not mud-coloured dreck.

What a long newsletter - and I’m just clearing my throat! There’s a chapter on machines in my forthcoming HUMANS: A MONSTROUS HISTORY so I’ll stop here for now.

Many folks have preordered HUMANS: thank you so much! The press is very pleased with the early interest (code: more publicity and marketing support for the book). I deeply appreciate all the ways in which folks have been supporting the book: preordering for themselves and as gifts; asking libraries to order the book; sharing photos of the book on social media; re-sharing my BlueSky posts about the book; agreeing to host book talks….

Thank you.

It’s thrilling that the book is already in the hands of many North American readers! Some preordered copies arrived a week ago - and the book’s North American official release date is February 4th! The official UK release is now March 4th. And you can already order it online or in person from anywhere that books are sold, anywhere in the world!

UK PhD funding competitions never awarded me a studentship - not even when I had completed four years half-time and published articles in academic journals. Go figure. ↩

If you’re feeling discouraged, know that the dissertation story ending was a happy one: I got a PhD and then turned it into a damned good book: Renaissance Ethnography and the Invention of the Human: New Worlds, Maps and Monsters (Cambridge University Press, 2016). If you fancy a maps, monsters, and exploration nerd-out, click here for buying links. ↩

In the years since that Jurassic era, a published facsimile of the atlas appeared. You can even consult digital images on the Bibliothèque Nationale de France’s Gallica website. ↩

OK, not thrown exactly. But nobody went and re-catalogued the millions of items to 1970s standards. That would have taken way too long. ↩

Add a comment: