A bear called Paddington: who gets to be human?

I’ve been re-reading the Paddington Bear books. If you’ve never encountered this bear, or have only done so via the movies, rest assured that the books are a fun, lyrical read for even folx who are double digits years old.

The action begins on a platform in Paddington Station in London. The year, we imagine, is 1958, when the book first appeared. Mr and Mrs Brown await the train on which their daughter is returning from boarding-school. The Browns are about to have an alien encounter with a bear in “a funny kind of hat,” a “small, furry object … sitting on some kind of suitcase.”1.

The creature begins as an “it” with a neck wearing a label, a being from afar judging by the suitcase emblazoned with: “WANTED ON VOYAGE.” Up close, they appear to be “a very unusual kind of bear.”

The moment of first contact is as genteel as it is surprising. Bear raises hat and greets humans in English, enquiring whether the humans need help. Humans learn that the bear hails from “Darkest Peru” and stowed away on a ship because his guardian, Aunt Lucy, “had to go into a home for retired bears.” The bear had just made a marmalade-fuelled trip to England hiding in a lifeboat, fulfilling Aunt Lucy’s fondly-held dream that he “emigrate when [he] was old enough.”

Almost seventy years after the book was published, the Brown family’s instinctive recognition of the bear’s, well, humanity, is as appealing as it is dissonant in an era in which refugees, new arrivals, and people who look different from a made-up norm are routinely monstrified and dehumanized. The bear wore a now-famous label: “PLEASE LOOK AFTER THIS BEAR. THANK YOU.” The words galvanized into action Mrs Brown, who couldn’t bear (sorry) the thought of abandoning someone with “nowhere to go” in London. Surely the bear would be “such company” for the children, who would “never forgive us if they knew you’d left him here.” She insists that Mr Brown get the label off the bear’s neck, for fear that it “makes him look like a parcel” - like an object rather than a person.

Despite Mr Brown’s misgivings about what the law might say, he asks the bear if he would like to go home with the family, to which the answer is an enthusiastic yes. The rest is history: the bear the Browns name Paddington (since his existing name is, as he put it, “only a Peruvian one which no one can understand”) goes home with the Browns, there to live a happy and zany life of discovery and misadventure as he muddles through the weird little world of suburban London.

Animal-centred children’s stories are fundamentally utopian. From The Wind in the Willows to The Muppet Show, beings in various shapes, colours, and sizes have no difficulty recognizing one another’s personhood. The Paddington stories evoke joy and wonder at someone who messes up the supposed boundaries between categories. Unlike stories in which the main characters are equally imaginative (talking animals; muppets), the Paddington books keep us in the space of the uncanny by having only one monstrous character.

Paddington broke all the category boundaries, starting with the biological (between human and bear). He challenged cultural boundaries: he was more British that the British when he emigrated from Peru, thus messing up the distinction between citizen and foreigner. He transcended political boundaries: as a stowaway, he had no legal right to live in the UK, yet there he was and still is, an icon of London. He was a young bear - an orphan - yet had the gravitas of a grownup. Despite Paddington’s category-breaking (monstrous) characteristics, the arc of the books reveals a bear who stepped off the boat as an inalienable element in the fabric of British society. Paddington’s creator, Michael Bond, framed Paddington’s peculiarities as wonders to be celebrated, not censured.

In 1964, several books into the series, Paddington Marches On ends with a birthday party for Paddington. Halfway through, Mr Brown announces that Paddington had received a telegram. Aunt Lucy would soon be turning a hundred, and the warden at the “Home for Retired Bears” thought she would appreciate marking the occasion with her family. (Fyi: bears have two birthdays a year.) Mr Brown had already made enquiries about travel, and had been promised a ship’s cabin for Paddington “at special bear rates,” with a steward who knew Paddington’s likes and needs. After three years, it looks as if the Brown family will finally be shot of their unexpected houseguest.

But the family is far from happy. When Mr Brown attempts to look on the bright side of a house sans bear - “no more marmalade stains on the walls” - the housekeeper Mrs Bird insists that “I shall leave them on. I’m not having them washed off for anyone.” Mr Gruber, Paddington’s antique shop-owning friend, recognizes that it’s only right that they help Paddington return, for Aunt Lucy’s sake: without her foresight and guardianship, “we should never had met him.” Mr Brown voices everyone’s fears: if Paddington decided to remain in Peru post-birthday, they “can’t really stand in his way.” Yet Paddington was now so much a part of their family that “it was almost impossible to picture life without him.”2

When the end of series seems imminent and the pages are wet with tears, Paddington, who had gone upstairs to pack, returns with his suitcase. The family is baffled that that’s all he plans to take: most of his possessions are still in his room. Paddington explains: “I’m only taking my most important things.” “I thought I’d leave the rest here for safety.”

He’s planning on returning to London!

Paddington is both unlike and like a British human person, his pratfalls highlighting tacit knowledge and arbitrary conventions (all the better for tripping up newcomers) while he carries around emergency marmalade sandwiches (yes, this is a thing). He’s also unlike and like a person from somewhere else, be that a visitor, immigrant, refugee, or orphan. In the real world he is of course nothing like any of them - he’s a stuffed bear living the saccharine life of a children’s story character. But he makes us think about how people are treated in the here and now. And he makes us think about how people were treated when Bond wrote the Paddington books, in the early years after the Second World War, when the UK and other countries in Europe invited people from their (former) colonies and from neighbouring countries to work and even to emigrate. These newcomers were essential to address labor shortages, and to rebuild cities destroyed during the Second World War.

Paddington has been derided as a model immigrant: how convenient that he turned up speaking English and willing to live the life of a curiosity - a pet. In a surreal collision of the real world and the world of story, when the producers of the latest Paddington movie requested a replica passport for Paddington-the-movie-character, the (real) UK Home Office provided Paddington with an official passport - hardly the welcome that the average refugee receives. (The special observations bit says “Bear.”)

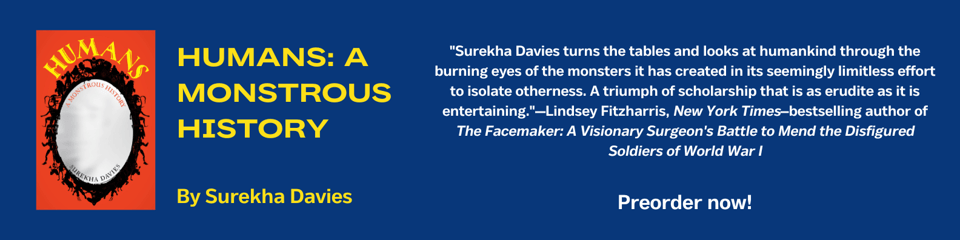

This stunt echoes an even weirder one from 2017, when Saudi Arabia granted honorary citizenship to an android named Sophia, the brainchild of Hanson Robotics, a Hong Kong-based company, an episode I discuss in my forthcoming Humans: A Monstrous History. One might say that Sophie is another sort of model immigrant, one that, like Paddington, is not even real, and thus a character to whom a country might safely extend citizenship without actually recognizing the humanity of the people near and far who labour so that others can have more wealth and power.

While many who support Brexit and people who demonize refugees and immigrants want ethnically homogenous nations, the imaginative space of the Paddington Bear books, about a person at once different and yet quintessentially British, as someone who expands the horizons of possibility for everyone around him, reveals an alternative, cosmopolitan, utopian ideal for Britishness.

That, then, is a way to both have the birthday cake and eat it. And it involves humanizing, not monstrifying, those who reveal to us different ways of being human - and of being ourselves.

Humans: A Monstrous History is available for preorder. Please consider preordering or asking your library to order it. You can also support my work for free by spreading the word! Just check out this newsletter for suggestions.

Live and virtual book talks

Thank you everyone who attend my virtual book talk for the Harvard Renaissance Seminar in Halloween week! I so appreciated your enthusiasm and thoughtful questions. I thank the organizers for the opportunity to do one of my favourite things: to talk about monsters and monster-making. More talks are happening! They include:

New York City: January Jan 3-6, 2025 (American Historical Association conference).

Virtual: Mon Feb 24, 12 noon ET, John Carter Brown Library.

Washington, DC: Tuesday March 4, 7pm, Politics & Prose Bookstore, Connecticut Ave.

Pasadena, CA: Friday March 7, 11:45-1pm (followed by lunch), Huntington Library

Pasadena, CA: Friday March 7, an evening book event (details tbc).

Palo Alto, CA: March 10, 4:30pm (ish), Stanford University.

Berkeley, CA: March 14, 4:30pm (ish), UC Berkeley.

Boston, MA: March 20-22, 2025 (Renaissance Society of America and Shakespeare Association of America joint conference).

Middletown, CT: March 25, 4:30pm, Wesleyan University.

Northampton or Amherst, MA: March 27, early evening, Five Colleges Renaissance Seminar.

New York City: April 7, 6pm-ish, New York University.

New York City: April 9, 6:15-ish, Columbia University.

Philadelphia, PA: Thursday April 17, Science History Institute.

YouTube livestream: Thursday April 24, 7pm ET, The Peculiar Book Club.

London, UK: Sunday April 27, The British Library.

London, UK: Monday April 28, King’s College London.

Add a comment: