Steve travels #32: Hello, Helioplex!

The moment I heard about the Helioplex, not far from Tashkent, it was at the very top of a very short “must-see” list. A monument to Soviet hubris, a fascinating piece of modernist architecture, or an absolutely unique piece of engineering history, it was so far up my alley it was going to need help turning around.

You know how if you get a parabolic mirror on a sunny day, you can cook meat at its focal point? Take that concept and make it gigantic. The helioplex takes a few hundred large mirrors to bounce sunlight onto a gigantic dish composed of thousands of smaller mirrors, to produce a concentrated beam of solar energy you wouldn’t want to stand anywhere near.

You might be thinking, “oh, a solar power plant”. But no. The helioplex does not produce electricity, but heat, at over 3000ºC, for a variety of industrial purposes. Producing novel materials, testing the resilience of ceramics and other materials under extreme conditions, the possibilities seemed endless to the Soviets who finished building it in 1987. Three years later their Union collapsed and the Institute of Solar Physics began a long slide into disrepair.

My sparse information on visiting it suggested it was open weekdays for visits. It’s over an hour by (very cheap) taxi but as I catch my first glimpse, I’m beyond excited. It’s so cool! The Soviets sure had their periods of dreary functional architecture, gigantic slabs of concrete built on the cheap, but this is their other extreme: it’s artistic, futuristic, a gleaming beacon of optimism and ambition perched on a hill overlooking the town of Parkent, surrounded by the tiny village they named “solar” in its honour. The only comparable complex in the world is the Odeillo solar furnace in France - perhaps ironically a drab “function over form” affair of very similar scale.

I stride purposely towards the front gate and am met with a warm handshake from a man acting like I’m the last guest to the party. He ushers me into the main Institute building, which is undergoing noisy renovations, and towards a tour group standing around a scale model of the complex, receiving an enthusiastic lesson from two guides.

It’s a great plan, with just two drawbacks. First, it’s in Russian. Second, this is just a random group of tourists, but a class of international students who have come to Tashkent to learn Russian. Their teacher asks, “Do you speak Russian?” and is quick with her follow-up, “Why not?”

I don’t know how to answer that one, so I say, “I speak French?”, to which a young French woman immediately comes over and offers to be my interpreter. This mostly consists of her chiming in once every few minutes with a muttered translation like “3000 degrees” or “it doesn’t work”. The person I mistook for a second guide is actually another teacher, translating “hard Russian” into “easy Russian”. Her gestural translation of the word “earthquake” doesn’t even need words - I can catch that one just fine.

Outside we get the standard demonstration of a small-scale solar cooker, instantly setting fire to a piece of wood. They ask if anyone has some food to cook, and I offer a piece of bread. Five minutes later, it’s warm bread. Things only really get cooking when a stereotypical mad scientist arrives, complete with lab coat and dark glasses. He leads us to a much bigger concentrator, several metres across. He slowly swivels one of the large flat mirrors to face the concentrator. Then he raises a bar of metal to the sweet spot, and within half a minute, there are sparks flying and a glowing red hole is burnt into it.

The teacher is actually very nice, and keeps taking me aside to explain things - it’s her third time taking students here, and she knows the place pretty well. She used to teach a course in Russia, but with visa difficulties, it has been more practical to move the class to Tashkent.

Next up, the scientist puts a ceramic brick in the firing line, and it’s truly impressive seeing a hole immediately melted into the side, staying glowing hot for a minute afterwards.

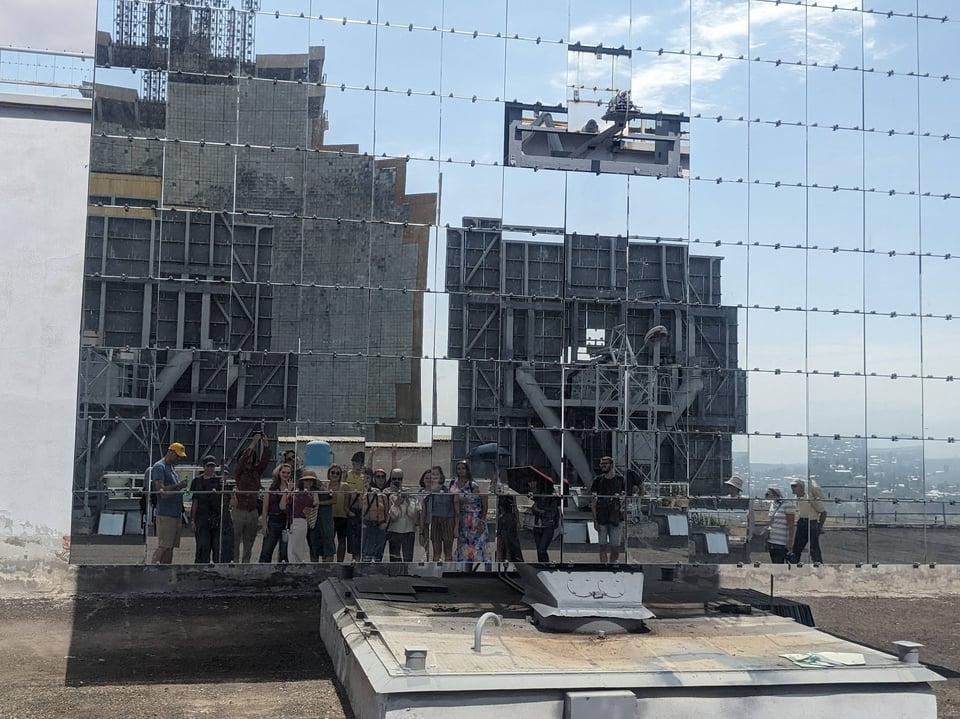

But I just can’t take my eyes off the big mama next door, its huge, gleaming curved surface unlike almost anything I have seen before. It stands with its back to the sun, ready to receive the reflected light from an array of individually positioned mirrors, but it has clearly seen better days.

It looks like the top section is missing all its mirrors, but I can’t get a clear answer on whether it is still functional at all, or not.

Finally, we go inside, to climb up to a viewing platform at the very top. Inside, it is a huge assembly of interlocking steel trusses, beautiful in its own way, and well frequented by a local pigeon population. This structure is also being renovated in some way, and there are workers and equipment all about, although nothing much is happening right now.

We climb the stairs to the first landing, and pass in front of the elevator. The doors are wide open, and there is nothing stopping you falling straight down the shaft. No signs, either. “That’s weird”, I say. We climb to the second landing, and it’s the same thing. That’s not good. Third landing, and my stomach is really turning. There are four more levels to go. I can’t do this any more.

I’m usually able to push through a fear of heights when the fear is unjustified, and the structure itself is safe. But this is hitting a nerve - it’s completely unsafe, and we weren’t given so much as a warning. I turn to descend, gripping the hand rails tightly, and find I’m not the only one. The French girl reveals she nearly fell into it - she thought it was some kind of store room, and nearly stepped in to take a closer look, only catching herself just in time. We regroup on the ground floor and they celebrate the joy of being alive by quizzing each other on Russian verbs.

That concludes the tour, and the group zooms off, leaving me to wander back down the road and grab a few more photos. I’m so chuffed by the experience - it’s everything I hoped for, plus a bit I didn’t.