Hadestown, Woody Guthrie, and the hoping machine

How a Broadway musical continues the legacy of one of America's most beloved folksingers.

How do you keep your head up and hope alive when faced with environmental disaster, a growing gap between the haves and have-nots, and a global rise in political scapegoating, nationalism, and extremism?

These questions aren’t just plaguing me & everybody else panicking in your Instagram stories. They’re the same questions that troubled Oklahoman folk singer, writer, and labor organizer Woody Guthrie. You may know him as the songwriter behind “This Land Is Your Land”, which most American kids learn in school as a kind of national campfire singalong.1 You may also know him as the originator of the phrase “This machine kills fascists,” which Guthrie - who wrote songs for U.S. soldiers during WWII, as a member of the Merchant Marines and the Army - painted on his guitar, and which isn’t generally mentioned to the six-year olds during singalong hour.

In 1943, Guthrie wrote & doodled a list of “New Year’s Rulin’s” to get himself shipshape before the birth of his son Pete. Some of my favorites:

Wash teeth if any

Read lots good books

Don’t get lonesome

Stay glad

Help win war - beat fascism

Keep hoping machine running

I’ve been listening to, thinking about, and singing a lot of folk music this past year, including Guthrie’s songs. As author Charlie Jane Anders writes in her Feb 12th newsletter, “In some ways, I can often get more inspired by stories of resistance and resilience when they aren't quite so closely related to the situation we're in right now. … It sounds counterintuitive, but learning something about the history of ship-making or ancient funeral practices can be better for my fighting spirit than yet another resistance newsletter.” In my case, that’s meant learning about the folk movement’s part in U.S. counterculture from the 1930s-60s, and learning a lot of great songs along the way.

So in this inaugural edition of Roll for History, let’s talk about Woody Guthrie, his influence on the folk-mythology musical Hadestown, and the hoping machine.

Hadestown (2019) retells the Greek tragedy of a miracle-working musician, Orpheus, who descends to the underworld after his wife Eurydice’s death. His music’s so beautiful that it convinces the King and Queen of the Dead to let Eurydice go home with him—on one condition. Orpheus must walk all the way back to the land of the living with Eurydice at his back, and he must never look behind him to make sure she’s still following.

Of course, it’s a tragedy. Orpheus turns around.

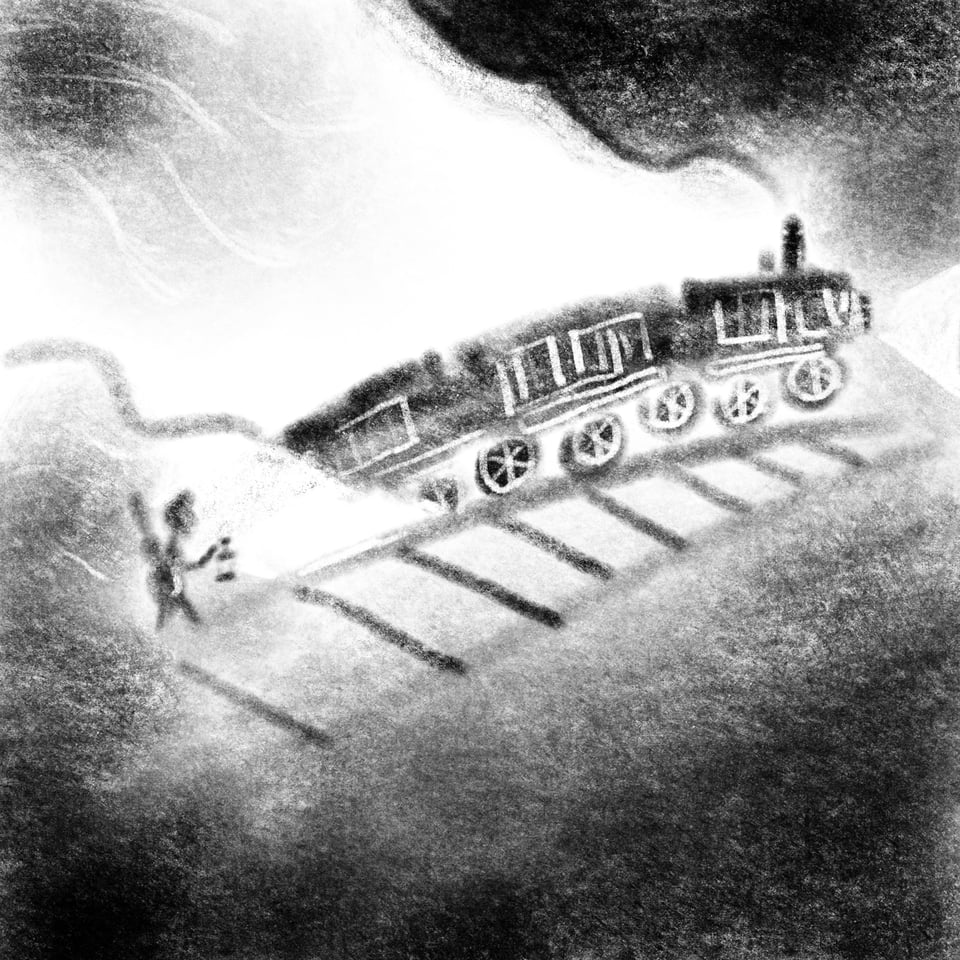

The musical takes these bones and casts them in a setting like the Great Depression (1929-1933): Orpheus is a poor boy with a guitar, Eurydice is a hungry young woman in need of work, and Hades is the boss of a company town whose workers are employed in the construction of a never-finished wall.

The same threads which motivated Guthrie’s work run through the lines of Hadestown. “So Long, It’s Been Good ta Know Ya” (Guthrie) describes the Dust Bowl as not just bad weather, but cataclysmic—the end of the known world. The storm “dusted us over, an’ it covered us under / Blocked out the traffic an’ blocked out the sun”. Young lovers say their goodbyes instead of planning marriage, and the town preacher warns his parishioners this may be their last chance for salvation.

Eurydice’s complaints, in “Any Way the Wind Blows”, strike a similar chord for our modern climate:

Weather ain’t the way it was before

Ain’t no spring or fall at all anymore

It’s either blazing hot or freezing cold

Any way the wind blows

This imbalance in the seasons, we’re told, comes from the lost love between Hades & Persephone. Hades is “king of oil and coal” whose “loneliness moves in him, crude and black”. The more he misses her, the tighter he clings, and more she loathes him. The “oceans rise and overflow.” Summer and winter lose their balance.

Of course, while Hades’s dominion over oil & coal speaks to the fossil fuels contributing to global warming (and his mythological association with wealth), it also echoes the company towns that sprung up around coal towns of the 1930s.2 The chorus are credited as the Workers and spend the second act building the walls and industry of Hadestown.

Walls being the key word here. At the end of Act I, Hades rallies the Workers to his cause with the ominous “Why We Build the Wall” (written in 2006, believe it or not). Its lyrics take the form of a call-and-response, and you don’t need me to tell you why it resonates:

What do we have that they should want?

We have a wall to work upon!

We have work and they have none

And our work is never done

My children, my children

And the war is never won

The enemy is poverty

And the wall keeps out the enemy

And we build the wall to keep us free

That's why we build the wall

We build the wall to keep us free

“It’s a love story,” Anaïs Mitchell, the songwriter of Hadestown, says. “But politics really is romantic.” Mitchell is a folk musician, and Hadestown was a concept album performed in folk venues long before it was a Broadway show. Like Guthrie, Seeger, Baez, Dylan - all the folkies who came before her, whose music has been in my ears for months - Mitchell doesn’t shy away from making a point.

I get what she means by the romance. The day-to-day reality of politics - voting when it feels hopeless, writing letters to your representatives, watching people stir up hate for clicks and votes - is an endless slog. You fix something once, and it breaks again.

But Orpheus isn’t a romantic hero just because he’s a great musician. His gift is the gift of fantasy, of hope: to “make you see how the world could be, in spite of the way that it is.”

I saw Hadestown in London while feeling pretty hopeless. I’d booked a vacation after a hard summer and felt like my tightly-held years-long dream - living in the UK, teaching the arts - was crumbling around me. That I’d been a fool to try.

When Orpheus cracks open the wall around Hadestown, the first thing that happens after he finds Eurydice is that Hades laughs in his face, tells him to get out, and orders his workers to beat the shit out of the poor kid. The Fates (a powerhouse trio of terrifying women) don’t literally kick him while he’s down, but they do ask him why he bothers trying - nothing changes.

Lying on the ground, bruised and bloodied, Orpheus ignores them. Instead, he asks the workers - who just beat the shit out of him! - if they agree. If it’s true.

When they stop and listen, he follows it up with another question: Who’s telling you that nothing changes? Why do they want you to think it’s true?

By the end of the song, they’re threatening to bring down the walls they’ve spent their whole afterlives building.

In the audience, I felt some of my own walls start to crumble. For the first time in months, hoping didn’t feel like a foolish thing.

Guthrie’s songs don’t flinch from the realities of the Great Depression, but they’re never without hope. Even “This Land Is Your Land” answers one of the verses cut from school recitals - where the singer sees a long line of hungry people at the relief office and asks “Is this land still made for you and me?” - with a resounding Yes.

“I hate a song that makes you think that you are not any good,” Guthrie wrote. “[…] I am out to fight those songs to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood. I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world and that if it has hit you pretty hard and knocked you for a dozen loops, no matter what color, what size you are, how you are built, I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself and in your work. And the songs that I sing are made up for the most part by all sorts of folks just about like you.”3

When you walk into Hadestown, there’s a good chance you know the story already. Myths get invented and reinvented and passed between cultures, the same way that folk music does. (I got into Guthrie through contemporary indie musician Mitski’s cover of Pete Seeger’s “Coyote, My Little Brother”.) Starting with a common understanding of the story lets you play with the beats. It lets you identify the ways that moments in history resonate with each other — today and the 1930’s and ancient Greece.

In Hadestown, the hoping machine isn’t just a metaphor. Music doesn’t just make people feel better: Orpheus’s song produces flowers from thin air, levitates him, and sets the seasons to rights by reigniting the love of the gods. “If It’s True,” his song to the workers, threatens to bring down the walls of Hadestown by uniting the people who were — a second ago! — building that wall and kicking him for daring to cross it.

Which is to say, Hadestown tells us that our music and art can wake up our senses to the world. Orpheus convinces Eurydice that life can be more than just survival; he wakes the workers up to their power and tries to lead them out of Hadestown; he wakes Hades up to the fact that he and Orpheus are both just men in love; and he insists that hope in hard times is a necessity, not a luxury. The fact that Orpheus ultimately fails isn’t the point. The point is that he tries. That we can believe it might work out this time.

Hope, in Guthrie’s music and in Hadestown, isn’t only a feeling: it’s a choice to stand up when you get knocked down. Hope is connecting with your neighbors. It’s washing your teeth (if any) and staying glad. It’s hearing the voice that tells you nothing changes, and deciding to try anyway.

Side Quest

A few things I do to keep my hoping machine running:

Play tabletop roleplaying games with my dear friends. (Currently playing Monster of the Week and Vampire: The Masquerade - where my character’s inspired by “what if Woody Guthrie got turned into a vampire” - but I’m also excited to try Yazeba’s Bed & Breakfast soon.)

Ordering books from the library instead of letting them languish in my Storygraph/Goodreads/equivalent forever (most recent read was August C. Clarke’s Metal From Heaven, which is very relevant to this essay)

Not using social media to keep up with the news. No, seriously. Can’t do anything ‘bout anything if I’m tired and exhausted from panicking all the time.

Learning to identify birds by their song (and embracing my own New Year’s Rulin’, which is to read the Wikipedia article about any new bird I see. One of my new favorite things is reading how Wikipedia editors try to describe birdsong. Great horned owl calls can include “a growling krrooo-ooo note pair, a laughing whar, whah, wha-a-a-a-ah, a high-pitched ank, ank, ank; a weak, soft erk, erk, a cat-like meee-owwwwww, a hawk-like note of ke-yah, ke-yah, and a nighthawk-like peent.”)

What about you?

“This Land Is Your Land” was recently played at the Trump inauguration. I’m not sure that Guthrie, who penned the song “Old Man Trump” critcizing Fred Trump for refusing to rent to Black tenants, would have chosen to perform at the occasion himself. ↩

Or entire counties, such as - famously - Harlan County, Kentucky. ↩

Bound for Glory, 1943. ↩