#1 : On Grokking

Prologue: What is this thing?

Some of you know that I have been doing a strange thing called a learning marathon the last few months. I might have talked your ear off about the nerdy (but cool) things that I am learning. Some of you have been on this learning marathon journey with me. (Hi! 👋)

Officially this is one my experiments/prototypes/outcomes from the learning marathon - inspired by my buddy Steph. An experiment in connecting with the people I know, in a way that feels strange, and somewhat formal. It is also a personal challenge for me to articulate my thoughts in a digestible format that might be interesting, amusing and maybe even useful for others.

Officially I set out to understand and explore the climate crisis, game design and implications for my design practice. And I have learned about those things - but I've also taken detours into other unexpected and fascinating topics. This newsletter is my in-flight synthesis - my way of making sense of things and sharing as I go along. Each piece will be an exploration of a theme or idea that I have been obsessing about. Or not. I'm going to make up the rules as I go along. 🙃

So onward.

On Grokking

What on earth is grokking?

Grok: To understand something so thoroughly as to become one with it.

Grokking is a neologism i.e. a made-up word ( aren’t all words made up 🤔) from Robert Heinlein’s 1961 book Stranger in a Strange Land.

Grokking is the thing that lets a musician pick up an instrument they have never played before - a pianist strumming a guitar - to play around, experiment and ‘grok’ how to play it without someone teaching them. Or how if you are a gamer, the patterns and reflexes you learn from other games help you grok the rules or the problem space and quickly orient yourselves.

Its a form of pattern recognition. A level of understanding that doesn’t live entirely in the cognitive, intellectual realm. In both the examples above, the body seems to be involved too. Reflexes or muscle memory that seem to work without conscious effort.

Image: Alto’s Adventure

Image: Alto’s Adventure

Muscles don’t have memory. What we mean when we say muscle memory is that the autonomous nervous system is kicking in. So to grok something is not just learning it in a cognitive way or to react to it in an instinctive, ‘reflex’ way but it is a level of understanding that is somehow both.

Daniel Kahneman talks about System 1 and System 2 in his book Thinking Fast and Slow. Simply put - There is an automatic, fast, heuristic system and a slower cognitive system. Let’s try and expand on that idea a little bit.

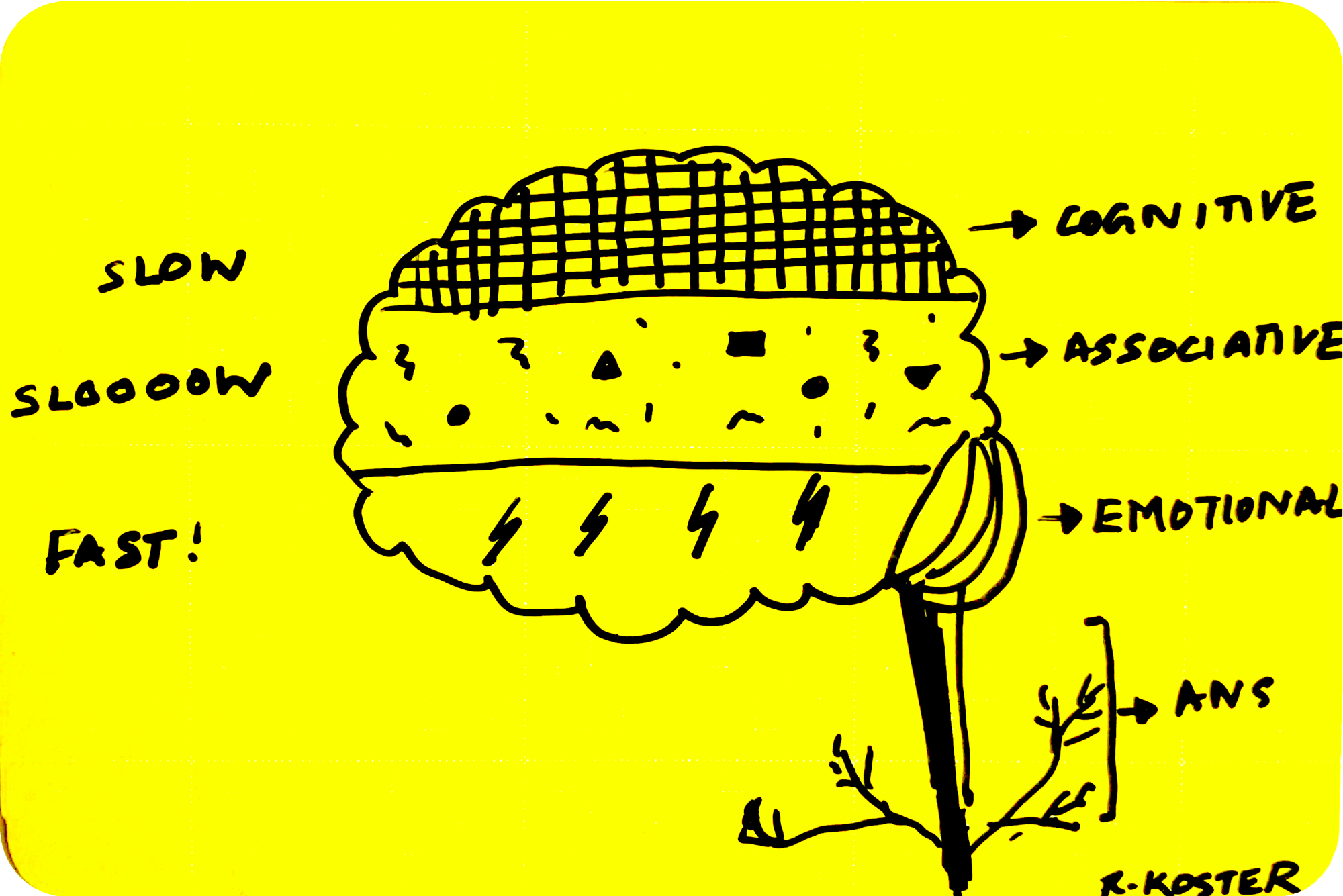

Here is an entirely biologically inaccurate layer-cake diagram of the brain inspired by Raph Koster’s model in the Theory of Fun for Game Design.

On the top is your cognitive, intellectual layer. This system is slow, logical and deliberate. This is the bit we measure during IQ tests. The middle layer is the integrative, associative part that isn’t directly accessible but is working to chunk down reality and make sense of it. Eventually turning into common sense. This bit might sound like Kahneman’s System 1 but is not - according to Koster, it is a much slower system than the cognitive layer. Finally the third layer, is the emotional brain and the autonomic nervous system (ANS). Lets call it muscle memory even though we are talking mainly about the ANS here. 'Muscles' themselves are just responding to the brain and nerves but muscle memory is an evocative concept nonetheless and one we are all familiar with.

Muscle memory (ANS) has been long thought to be a dumb system. Put your hand on something hot and you pull it back before the signals reach your brain - what it probably really means is that it hasn’t reached certain bits of your brain, likely the slow cognitive bits. So you think that you didn’t use your brain but you probably did.

We are learning that reflexes are a lot more intelligent than we gave them credit for. The ANS is constantly monitoring cues from the environment and is responsible for regulating how the body prepares to deal with any threats i.e. our stress response. As Dr.Porges says - this information is not processed by the brain on a cognitive level but on a neuro-biological level.

So the same learning system and feedback loops involved in grokking games or musical instruments is involved in building and storing instincts and ‘muscle memory' about stress and danger.

This is fascinating to me for many reasons. Like most people I’ve grown up with old associations of these words - learning happens in the brain, emotions happen in the heart (we know its not the heart but we imagine it to be some mushy dismissible part of the brain), instincts are things that are come out of the box - things you are born with.

But these new definitions are more freeing and feel more true to my lived experience. There is more of a cohesiveness in the way that the brain and body interact. (At least there is meant to be unless your brain is in denial about the stress signals your body is sending - which happens to individuals suffering from past trauma.) Learning happens in the brain and body. Emotions live primarily in your body. Instincts are just patterns you learn over time.

Games and Grokking

Games are a really interesting lens to explore some of these - learning, emotions, instincts, patterns and interactive systems.

The brain is constantly trying to problem solve. When you put a situation or problem in front of the brain, it tries to solve it. What games do really well is that they modularise problems and present slightly different variations of the problem space to the player (think different starting setups of a game of Catan or different levels of a video game) With the variations getting progressively harder as the player gets more familiar with the game. By allowing the player to practice repeatedly the game accelerates the grokking process. The result being an understanding that goes beyond the cognitive.

When do we need to go beyond learning? When is grokking useful and even necessary? Is it when we want the learned instincts to be experienced by the whole self - mind and body?

I don’t have answers but what the learning marathon process is teaching me is that it’s ok to sit with the questions. Some magical things can happen when I do.

Thank you for reading until the end. Hit reply to send me any feedback or chat further about any of this, or about nothing at all.

Notes & Credits 1. See Raph Koster's book on game design for more on grokking 2. Thanks to Matt McStravick for introducing me to polyvagal theory and Body Keeps The Score. 3. Kahneman talks about cognitive biases and Raph Koster and Stephen Porges' models of the brains are more neuroscience-based (how the brain and nerves actually work). They are related but not directly comparable. I put them together to see how they related purely out of curiosity.