Durang's Hornpipe

Copying tunes into my notebook is becoming one of my favorite things to do. As a general rule, old time fiddlers learn tunes by ear. Part of that is because you can’t get all of the nuance of a tune into written form, but I think mostly its just that people learn to play music from other people primarily by listening. If watching and asking questions are an option, those can be a huge help, obviously.

Really strong musicians are consistent in their playing. They have a well developed sense of how a piece of music - an old time tune, a symphony, whatever - is supposed to sound, down to really fine details. Some of that is about memorization, but a good deal of it is understanding the particulars of how music is supposed to sound.

For example, a couple of years ago I discovered the album “Reparations” by Jake Blount through some Spotify playlist. What I noticed was the feel of the rhythm played by the fiddler, Tatiana Hargreaves. She has this incredible shuffle, loose and easy and yet also metronomic. I’ve since discovered this is a hall mark of old-time fiddling that seems to come from its roots as dance music.

Anyways, Durang’s Hornpipe, it turns out, was not written by it’s namesake, John Durang (1768-1822). He was one of the first native-born Americans to become known as dancer, and was particularly well known for dancing the hornpipe, a traditional dance performed solo. He took violin lessons in the 1790’s from a German immigrant by the name of Hoffmaster (or maybe Hoffmeister?), who wrote the tune for him. It has been a staple of American folk dance pretty much ever since.

Durang was also responsible for making famous the “Sailor’s Hornpipe” - a tune known today through it’s association with the cartoon strip Popeye. Additionally, he was a skilled circus performer and stage actor, and perhaps the first American to perform in blackface, as Friday in a stage production of Robinson Crusoe. He grew up speaking German in Pennsylvania Dutch (which should really be “Deutsch,” as in “Deutschland”) country, and, at 17, joined the Old American Company, the first professional theater troupe in the United States. He apparently performed before George Washington a couple of times.

When I think of “old-time” music, the old-time I think of is, roughly, the period of American history between the Civil War and the Great Depression. The introduction of radio stations in the mid-1920’s and the rise of the modern recording industry (both made possible by the invention of the electric microphone) brings that era to a close, as it radically changes how music is transmitted. But also, I tend to think of the Roosevelt administration and World War II as a major turning point in American history. After the war, you have the rise of bluegrass and modern country music. Hence, the older tradition is “old-time.”

An older fiddle player I met at a fiddle camp once told me that, as a young man, he and his friends sought out fiddle players born prior to 1920. Those were people who had learned to play before radio became popular, who had first-hand experience of the tradition as it was transmitted from player to player. In Appalachia, the region most people associate with old-time music, this sort of tradition was pretty much strictly by ear, as many musicians did not read notation. But in the Midwest, musical literacy was pretty common, as church congregations sang from hymn books, and many households had pianos. And there are a good deal of tune books from the mid-19th century that one can find in dusty archives even now, such as Cole’s 1000 fiddle tunes.

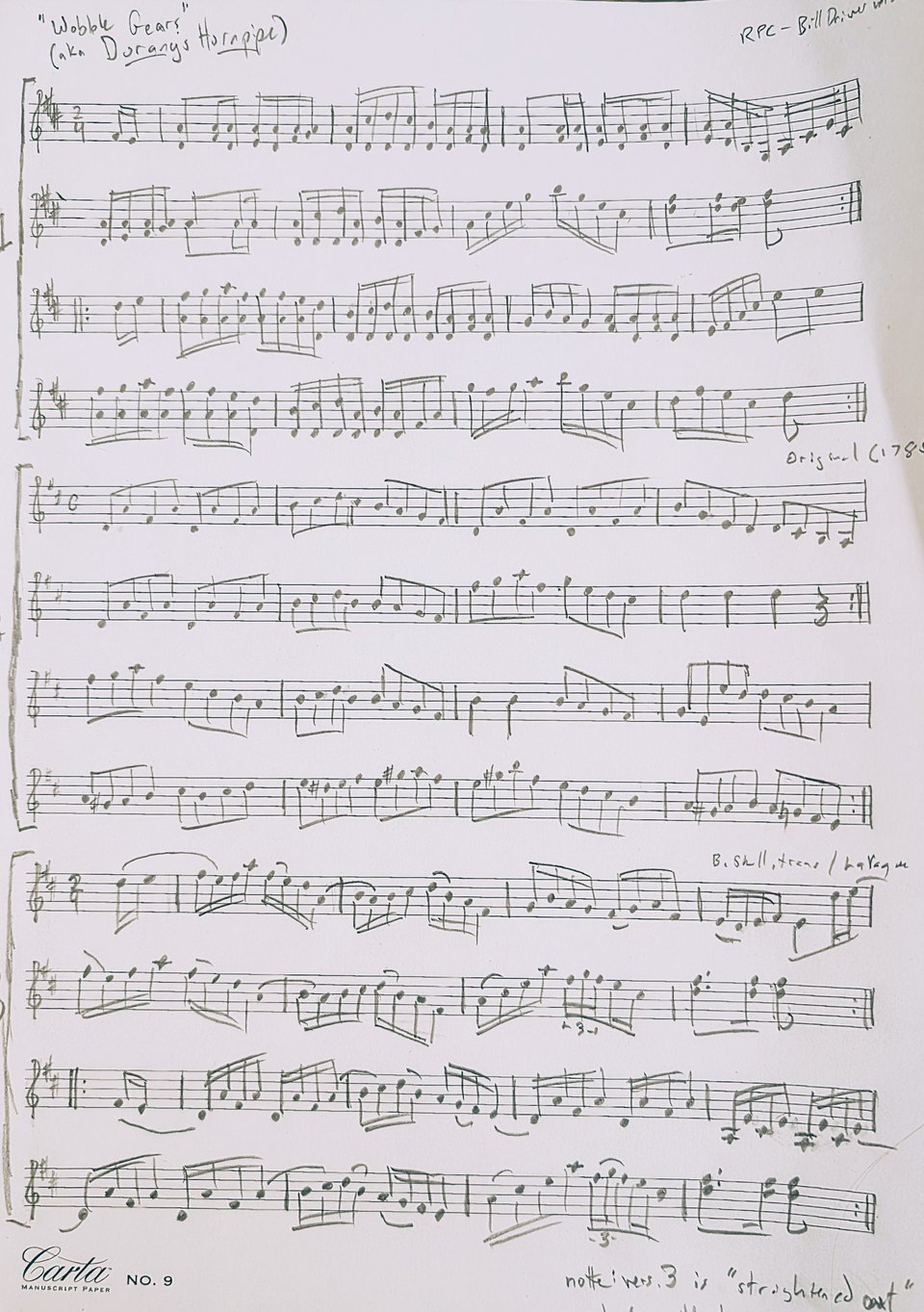

As I was playing around with the three versions I had written into my notebook, I realized that none of them would quite work for me. I’ll need to put something else together before I can really learn “Durang’s Hornpipe,” and I’ve been going through various recordings trying to piece that together. This, I’ve found, is a particular kind of trick in old-time music – you can play a tune differently near every time once you really know it. Add a flourish here, an accent there – if you know how it’s supposed to sound, you can really play around with it. I’m still just memorizing tunes, getting the patterns under my fingers, and I can get totally thrown off if I miss a note.

You can’t really capture tunes on paper, but writing them down has been useful to me. And I think it’s part of the tradition. In the classic Pennsylvania tune compilation “Dance to the Fiddle, March to the Fife,” Samuel Bayard notates numerous versions of tunes side by side. And that’s just one collection, taken from one part of the country. Durang’s Hornpipe is in there (at least I’m pretty sure it’s in there). You’ll find other versions elsewhere. How does one know it’s “Durang’s” and not some other tune? I suppose such is the stuff of many a late night discussion around the campfire.

Add a comment: