Thoughts on Government Lawyers and Responsive Government

Notes on law, governance, and other matters from Samuel Bagenstos.

Welcome to my newsletter. If you don’t know me, I’m a professor at the University of Michigan, with appointments at the Law School and the Ford School of Public Policy. I just got back from serving nearly four years in the Biden Administration. From Inauguration Day, 2021, until June 2022, I was General Counsel to the Office of Management and Budget. From June 2022 until mid-December 2024, I was General Counsel to the Department of Health and Human Services. I’m thinking of this newsletter as a place where I’ll offer quick responses when moved by things I read, and set down initial thoughts on various topics—thoughts that might crystallize into more sustained scholarly or public writing.

Today, I’m moved to post some thoughts on lawyering within the government—and, in particular, on the relationship between government lawyers and responsive government. My provocation is this post by Jennifer Pahlka. Pahlka is one of the interesting thinkers associated with the ideas that travel under the heading of “abundance” or “liberalism that builds.” I highly recommend her book about the difficulties of implementing government programs in an effective, responsive way. I’m about 85 percent on board with the “abundance” folks. I think they represent an intellectual-political movement that both is very important and has some significant flaws and limitations that need to be addressed. In some of my writing over the next few years, I’d like to deepen a few of the arguments of the movement while offering a (mostly friendly) critique of some of its important aspects.

Pahlka’s book identifies a number of reasons why implementation of government programs is too slow and unresponsive to the needs of the people (and even to the desires of the policymakers who designed the programs). But one pretty consistent theme is that those who try to implement novel, flexible, or fast-moving policies within the government find themselves constrained by unduly restrictive interpretations of law. Pahlka sounded that theme in a post she published a week ago. (That was my last day on the job at HHS, so I didn’t see the post until today.) The following paragraph, which I’ve bolded to make clear it’s her words not mine, crystallizes the point:

Take the issue of respect for the law. Put aside the headline grabbing issues for a second and live in the mundane world of implementation in government. If you’ve spent the past ten years trying to make, say, better online services for veterans, or clearer ways to understand your Medicare benefits, or even better ways to support warfighters, you’ve sat in countless -– and I mean countless — meetings where you’ve been told that something you were trying to do was illegal. Was it? Now, instead of launching your new web form or doing the user research your team needed to do, you spend weeks researching why you are now branded as dangerously lawless, only to find that either a) it was absolutely not illegal but 25 years ago someone wrote a memo that has since been interpreted as advising against this thing, b) no one had heard of the thing you were trying to do (the cloud, user research, A/B testing) and didn’t understand what you were talking about so had simply asserted it was illegal out of fear, c) there was an actual provision in law somewhere that did seem to address this and interpreting it required understanding both the actual intent of the law and the operational mechanics of the thing you were trying to do, which actually matched up pretty well or d) (and this one is uncommon) that the basic, common sense thing you were trying to do was actually illegal, which was clearly the result of a misunderstanding by policymakers or the people who draft legislation and policy on their behalf, and if they understood how their words had been operationalized, they’d be horrified.

Now, for the last four years I’ve been an agency general counsel. So it’s been my job to advise those who make and implement policy and tell them what the law says. And I definitely recognize the set of dynamics Pahlka describes in that excerpt, though it’s very much contrary to the way I tried to do my job (and to get my staff of around 800 professionals to do theirs). I thought it might be useful to lay out how I think agency counsel should approach the task of advising those who make and implement policy, and then to share some observations about why the dynamics Pahlka describe persist—and why they persist despite the desire of folks like me and many of my staff to make it possible for government to be nimble and responsive. None of this is particularly a critique of Pahlka’s post or of the broader abundance-build movement—though, as I said, I hope to develop some friendly critiques of that movement in future writing. My aim today is just to deepen and contextualize Pahlka’s points about law.

How Government Lawyers Should Approach Their Advisory Role

When I was going through my confirmation process for the position of HHS General Counsel, a lot of the Senators seemed to think of the job as being something like an internal police officer or district attorney focused on rooting out lawbreaking within the agency. They wanted me, above all else, to commit to making sure that HHS would follow the law—and to stopping those within the agency who wanted to violate it.

I was happy to make that commitment. In our constitutional system, the Executive Branch must operate in accordance with law. Article II requires the President to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed”—language that requires the President, and the Executive Branch he heads, to comply with and carry out the laws Congress adopted pursuant to its constitutional power.

But it’s not just legal formalism. Respect for democracy requires that executive officials comply with the statutes adopted by the people’s representatives. Even if I think some of those statutes are misguided or even deeply flawed—and believe me, I do!—democracy means that someone in my old job doesn’t get to decide whether they will be implemented. (If I thought carrying out the relevant laws was affirmatively immoral, rather than just in service of misguided policy, I wouldn’t take a job that required me to do so; there are plenty of jobs in the government I probably wouldn’t take for that reason.)

So I was happy to commit to ensure that my agency did not take action for which it lacked legal authority. But that turns out to be a very small part of the job of an agency general counsel—at least in a well-functioning agency. Sometimes policymakers want to take actions that are flatly inconsistent with legal requirements—that is, actions for which no lawyer could craft a professionally respectable defense. In those instances, the role of the agency general counsel is to tell the client they can’t do the thing they want to do, and to work to identify a lawful pathway for the client to achieve as much of what they’re trying to achieve as possible.

But most government officials who make and implement policy in well-run agencies have at least a general understanding of their legal authorities. They may want to read those authorities aggressively, but they tend not to simply disregard those authorities. They also understand their place in our democracy. As a result, most of the time there is at least a professionally respectable argument that what the agency client is trying to do is lawful.

As an agency GC, I sometimes found these arguments overwhelmingly persuasive. Other times, less so. But I did not believe that it was my job to require my agency clients to conform to the interpretation of law that I personally found to be the “best.” If I were a judge, that would be my job. But the President didn’t appoint me to be a judge. He appointed me to help him and his other appointees carry out his policy agenda. If I imposed my own views of fairly arguable legal questions to interfere with that agenda, I would be overstepping my place in a democratic, constitutional order.

Of course, even though I wasn’t a judge, I had to care a lot about how real-live judges would react to the actions my agency clients sought to take. We may have professionally respectable arguments for the lawfulness of our actions, but if a judge is going to reject those arguments and nullify those actions, maybe we should change our plans and use our limited resources on other projects.

In a world in which the Fifth Circuit exists, this was an ever-present danger for the Biden Administration—particularly in an agency like HHS whose work was highly ideologically coded. So although I very rarely had to tell a client that they had no authority to take the action they wanted to take, I constantly had to advise about litigation risk. We’d try to run down questions like these: How likely is it that someone will sue over this action? In what forum will they sue—and, in particular, can they maneuver themselves into the courtrooms of the judges who have demonstrated hostility to our initiatives? How likely is it that we can prevail in that litigation on procedural grounds (such as arguing that the plaintiff lacks standing, there’s no final agency action to challenge, or the action is committed by law to agency discretion)? If the litigation reaches the merits, how likely is it that we will prevail? And what’s the consequence—to this program, to related programs, or to the government as a whole—if we lose? (We also had to advise about other legal and legal-adjacent risks, like oversight risk—the risk that Congress, GAO, an IG, or another oversight body will say that the action was unlawful or wasteful—and precedential risk—the risk that taking this action today will constrain the agency from doing what it wants in the future, perhaps because a court will step in at that point. But I’ll focus here on litigation risk.)

My staff and I tried to give as informed answers to these questions as we could in the time we had available. (More on the “time available” point below.) And we left it to the relevant policymakers to decide whether the benefits of moving ahead with their proposed action would be worth the risk. Who were the relevant policymakers? That, to me, depended significantly on the extent of the consequences if we ultimately lost in litigation. If the only consequence was that the proposed action would be nullified, and the HHS component seeking to take that action would be back to square one, then I would often think it sufficient for the head of that component to make the decision. But if the issue was a high-profile one, or the consequence of a loss in court would be a ruling that constrained other HHS components—or other parts of the government—from taking important actions they might want to take, I would elevate the question to a higher level in the Department or even an interagency discussion.

The crucial point, though, is that merely identifying a litigation risk did not mean that I was telling my policy clients they couldn’t do what they wanted to do. We do, in fact, live in a world in which the Fifth Circuit exists. So in every case there’s a non-zero chance that a Department of Health and Human Services pursuing left-of-center policies will be subject to—and lose—litigation. We could not govern—we could not deliver what the President had promised the American people—if we refrained from doing everything the Fifth Circuit might enjoin. But even a very high risk that we would lose in litigation, with significant consequences for government programs beyond the one at issue, was not a basis for me to tell a policymaker no. Instead, I just wanted to be sure that the right policymakers, at the right level of government to take account of all of the relevant interests for the Department or the Executive Branch, were making an eyes-open decision that whatever benefit we would get from undertaking the proposed action was worth the risk.

Now, perhaps Pahlka or others would say that even this approach is too much process—it’s slowing down decisions, making it harder to respond nimbly to developing issues, etc. But we did try to be attentive to concerns about speed. When crises required immediate action—various flare-ups in the COVID pandemic or other infectious disease outbreaks, the need to construct a mechanism in real time to ensure that providers got paid when the Optum-Change cyberattack shut down a large chunk of the country’s health care reimbursement system, and many others—we relied on the good judgment and long experience of the staff of the Office of the General Counsel to provide our advice close to instantly. And more generally, I tried to apply a risk analysis to OGC’s own processes—because government inaction in the face of serious problems itself poses risks, I wanted to be sure that our advice came at a time that enabled the policymakers to be responsive to the particular problems at issue. And I tried to be sure that we were not effectively vetoing clients’ proposed actions by posing successive rounds of “just asking questions.” (I’m sure I was more successful at these efforts sometimes than others, and that people may disagree regarding how successful I ever was!)

And, with all respect to my friend and colleague Nick Bagley, process isn’t just a “fetish” of lawyers. It plays an important role in developing and implementing good policy. Defending this point, and identifying ways of thinking about what are the right kinds of process—and how extensive and intrusive it should be for various kinds of decisions—is part of what I want to do in future writing about the abundance-build movement. Here, though, I’ll just make a few points about why it makes sense to ensure that policymakers at the relevant level are fully informed about litigation risks before they decide what actions to take—even if providing the relevant information adds process. Resources within the government are limited. And even absent legal issues, good policymaking and implementation can take a lot of those resources. If, after a huge investment of staff time, a court sets a new policy aside, that is an enormous opportunity cost. And if the court goes further and makes it harder to adopt other good policies in the future, that’s an even bigger cost imposed on effective governance. As appropriate in light of the cost and urgency of a proposed action, policymakers should take time to think about the chances these consequences will ensue—and whether their proposed actions are in fact likely to generate benefits that are worth those risks. (I doubt Nick would disagree with that general principle, though there is obviously lots of room to argue about how to apply it.)

So Why Does Pahlka’s Story Resonate?

As I said above, I definitely recognize the dynamics Pahlka describes. I would say that people outside of general counsel’s offices in most agencies would describe their GC as frequently telling them they can’t do what they want. And people might say that about the office I led at HHS, notwithstanding that I worked pretty hard to make clear that we were almost never saying no; we were just trying to ensure that policy officials made their decisions with their eyes open about the relevant risks. Why do people in government consistently see the law—or the interpreters of the law within the government—as standing in the way of effective, nimble, responsive governance?

Part of the answer is what I call the “What we say/What they hear” problem. When I was HHS General Counsel, I would from time to time get a call from the head of some agency component, who said some version of “I want to do X, and OGC is telling me I can’t!” If the issue was sufficiently high profile, I would typically already know about the controversy and be able to explain that we weren’t saying they couldn’t do X; we were just saying they needed to weigh the risks, and potentially give real consideration to steps that we had identified to mitigate the risks. Sometimes, those steps were as straightforwad as providing an additional paragraph or so of explanation in the preamble to a regulation, as a means of fighting off an arbitrary-and-capricious challenge under the Administrative Procedure Act. If I were king of the world, I might well say that demanding that sort of additional explanation is a needless tax on governance that courts could not require. But in the world we do live in, I often thought adding a little text to a rule’s preamble was worthwhile if it could dissuade a court from scuttling a regulation that’s taken years of calendar time and thousands of hours of staff time to formulate. But the people who ran the policy process, understandably, often didn’t like people like me coming in and telling them to mess with the product of all that painstaking work. So they heard our suggestions about mitigating risk as objections to the product they had produced.

If the issue had a lower profile, so the outreach from the component head was the first time I heard about it, I’d reach out to the subject-matter experts on my team and find out what was going on. The overwhelming majority of the time, I saw that my team in fact wasn’t saying no; they were merely giving the client advice about the litigation risk of a proposed action and steps that could mitigate that risk. Or at least I could see that that’s what they meant to be communicating. But everyone’s so busy in the government, and the issues have such urgency, that communications often were a bit clipped. And so I could see how the client interpreted my staff as just saying no to the proposed action. The problem was compounded when, as happens when people are busy, my team didn’t fully explain what made the original proposal so risky, and the client accordingly didn’t fully address my team’s concern, and my team responded by flagging the concern anew. Repeated remands for more work sure can seem like a veto. To address these problems, I had to work to make sure my office more fully explained the nature of its concerns, gave more detailed (and hopefully immediately actionable) advice about how to mitigate risk, and made explicit that whether to take on a particular litigation risk was for the policymakers rather than for the General Counsel’s office.

And it’s also true that I sometimes did see lawyers taking the place of judges and telling agency clients that certain proposed actions would be unlawful, despite perfectly reasonable legal arguments to the contrary. My observation is that, throughout the Executive Branch, this sort of peremptory advice comes most commonly from attorneys who work in procurement law, appropriations law, and ethics. (A lot of the examples Pahlka focuses on involve procurement.) I can speculate why that is: Given the thickness of procurement-law rules, and the high likelihood that some potential bidder will be upset by any choice an agency makes in that area, lawyers who work on procurement must see avoidance of litigation risks as the overwhelming imperative. (And their clients probably do, too, because the client can’t put a new initiative in place if the Court of Federal Claims has enjoined the contract that is the vehicle for carrying out that initiative.) Appropriations and ethics law, by contrast, usually don’t present much risk of litigation—but they are areas in which oversight entities like GAO, the Office of Government Ethics, and the Office of Special Counsel can make very splashy public findings that embarrass the agency. Lawyers in these fields may understand their primary professional goal as avoiding that sort of embarrassment—for their agencies and themselves. And of course one can never underestimate the temptation of any given public official to acquire more decisionmaking power within their agency. If lawyers are empowered to say no to their policy clients even in the face of reasonable arguments for legality, they take on more prominence within the decisionmaking process of their agency. Consciously or unconsciously, that may lead many government lawyers to expand the zone in which they advise that a policy is unlawful, rather than that it merely poses litigation risk.

Some of the more interesting dynamics, though, come from outside of general counsel’s offices. I often found that it was my clients—the officials who had responsibility for making and implementing policy—who raised legal objections to particular proposed actions. Often, they persisted in those objections even once my office provided an analysis demonstrating that there were perfectly reasonable arguments that the proposed actions were lawful. They were often facing pressure—from outside stakeholders, Members of Congress, or higher-level officials within the Administration—to take certain actions that, for policy reasons or mere inertia, they preferred not to take. But rather than own up to those non-legal reasons, they wanted to be able to shut down the pressure by telling the outsiders that it would be unlawful to do what they were being asked to do. My sense is that this dynamic explains a very large fraction of the cases described by Pahlka in the paragraph I quote above.

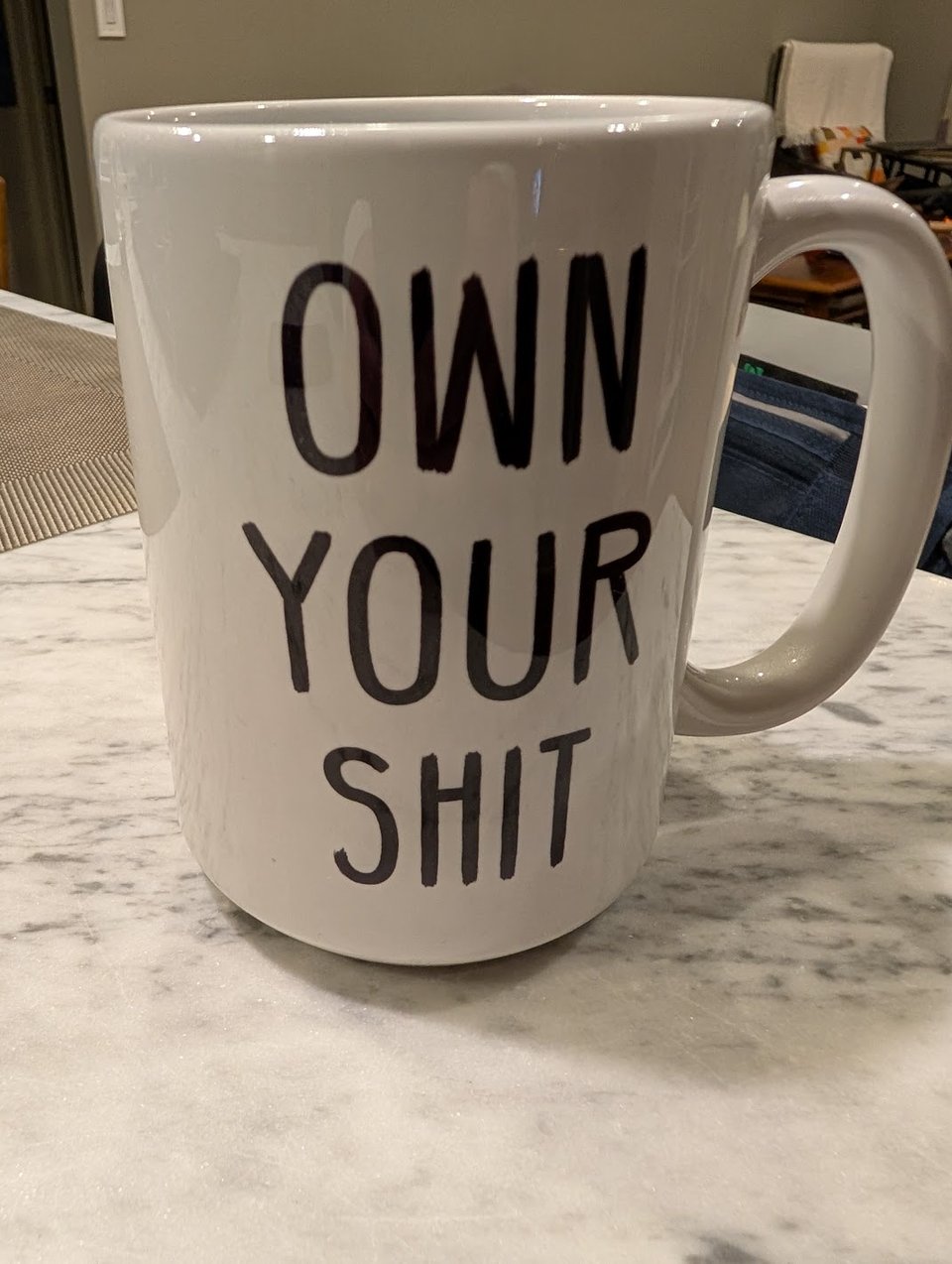

My response was always to tell the client that they had to take responsibility for their policy choices rather than say that they had no legal authority. They could talk about litigation risks if they wanted, but they could not say that they lacked legal authority. (I crystallized this principle as a basic rule of my office, “The Bagenstos Doctrine: Own your shit.”) But it was always a struggle to get folks to stop pointing to the law as a reason they couldn’t do what they didn’t want to do.

So how do we fix these dynamics? Contra Pahlka, I’m skeptical that an outside entity like DOGE, armed with AI tools to cut through legalistic chaff, will make much headway here. I think the answer is effective public management—both effective management of agency counsel offices, and effective management of the policy and implementation side of agencies. And it means very substantial reform of procurement rules—and of the process for challenging procurement decisions. Those, by the way, are key lessons I take from Pahlka’s impressive book. How to make it work? That’s something I may write about in the future. But I’m at nearly 4,000 words already, so maybe I should stop for now.