If The United States Is Conscious, Then Why Not An LLM?

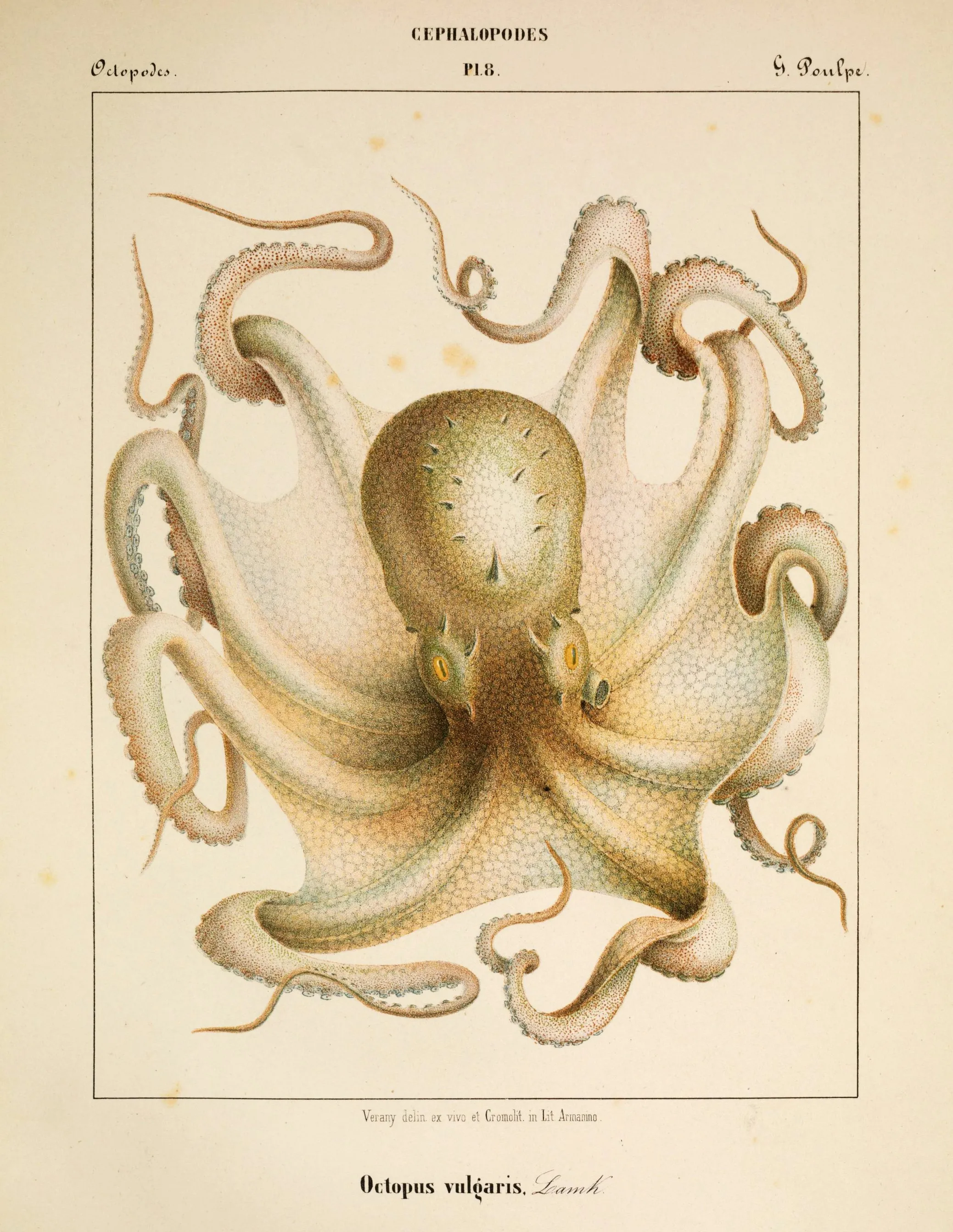

One of Jean Baptiste Vérany’s chromolithographs of cephalopods

I recently realized I may be one of the only people on Earth to hold this philosophical position: LLMs have no conscious understanding, but they may have phenomenal consciousness. That may sound like a contradiction, but I mean something subtly different by each use of “conscious.”

In the former case, I’m referring to “natural language understanding” as defined in Bender and Koller’s “Climbing towards NLU” — a mapping from speech utterances to communicative intents, aided by a shared “standing meaning” for utterances. For instance, if I talk about “walking my dog,” you understand what a dog is (because you’ve built a mental model of “dog” by interacting with them in the world and noticing that other English speakers refer to them as “dogs”), and you understand what my dog is (because you’ve read me talking about it before), and you understand why I’m telling you about walking my dog (whether that’s to explain why I was late to a meeting or, in this case, as a hypothetical example).

Large language models by definition cannot have this form of understanding, because they are traditionally trained on text and only text. They can learn word2vec-style associations between words — that a queen is the female equivalent of a king, or that Rooibos is the name of Russell’s dog — which, at the scale of “everything ever written,” enables LLMs to fake a comprehensive world model. However, though an LLM can “understand” a dog as a bundle of trained associations with other terms, it has no way to connect this to a “real” dog, and it has no way to connect the associated terms with their referents, and so on. In the context of the original “Climbing towards NLU” paper, that is the definition of a stochastic parrot — a system that can convincingly mimic having a mental model of the world, by producing coherent English language responses, that nevertheless has no grounded understanding in the real world and so cannot have communicative intents.

Bender and Koller fully admit in the paper that training on multimodal data, like video, might be enough to give an LLM at least some sense of grounded understanding.

Bender and Koller explore this via the “octopus test,” imagining an intelligent octopus listening in to the conversations between Alice and Bob. Given enough time and data, the octopus could convincingly stand in for Bob — but, having no experience of the landlubbing world, it’ll be out of its depth (literally) if something novel and unexpected occurs. That the LLM-as-octopus can imitate but not innovate is also the argument of a different set of authors in “Transmission Versus Truth, Imitation Versus Innovation: What Children Can Do That Large Language and Language-and-Vision Models Cannot (Yet)”. This distinction is the root of the “Gopnikist” position, that LLMs are cultural and social technologies and not thinking machines, which I roughly consider my own position.

In the latter case, I’m referring to “phenomenal consciousness” — the “What Is It Like To Be A Bat?”-ness of experience, that there is something it is like to experience reality from a particular viewpoint. When I see a red door, there’s some difficult-to-define sense that I know I’m seeing the color red, which I can introspect about if necessary.

Large language models may exhibit phenomenal consciousness in this sense. Consider my all-time-favorite philosophical paper, Eric Schwitzgebel’s “If Materialism Is True, the United States is Probably Conscious”. It argues for the proposition in the title — that if strict materialism is true, then the United States may be and in fact probably is phenomenally conscious in the above sense, that there is “something it is like” to be the United States. If the United States is conscious, then why not an LLM?

The argument runs roughly as follows. The only organism we’re confident is conscious is human brains. But if materialism is true, human brains are “just” interlinked neurons. Is there any good reason to think that swapping out the underlying material or making them slower or more distributed in space would make the organism “less conscious”? You may intuitively think so, but via a series of science-fictional thought experiments, Schwitzgebel argues that it’s actually more likely that you end up with something you would still call conscious.

This paper is also reprinted in Schwitzgebel’s The Weirdness of the World, which was one of my favorite books of 2024.

Notice that these two definitions are orthogonal. Hypothetically, a system could have conscious understanding and intent without any phenomenal experience — a p-zombie. On the other hand, we could imagine a system that has phenomenal consciousness with no grounding in the real world, no communicative intents, and no natural-language understanding. I’m one of the few people who would argue an LLM might belong in the latter camp.

Although we could hypothetically imagine a p-zombie, I’ve always been less than convinced that it could really exist. I suspect a sufficiently complex information-processing system inherently has phenomenal consciousness, along the lines of Integrated Information Theory, though that theory defines consciousness as sufficiently complex information processing.

Robin Sloan once asked the memorable question, “Are language models in hell?”. His answer plays on this distinction between understanding and phenomenal consciousness, so I suspect he might actually agree with my statement above.