Bird of Passage: August 2024

I have a big project this month: I’m editing the text for the forthcoming new edition of the National Geographic guide to the birds of North America. This has me thinking about field guides, and I’ve realized that although my kid loves to flip through the various field guides on our bookshelves, I rarely actually use them anymore.

It didn’t used to be like this. The first field guide I ever used was a very basic “Birds of Ohio” book that had somehow ended up on my non-birder parents’ bookshelves when I was a kid. Whenever someone asks about my “spark bird,” the bird that first captured my interest, I tell them about the time a mystery bird that I’d never seen before showed up under the seed feeder my parents put out in winter, mixed in with the usual chickadees and sparrows. I paged through that book and determined that it was something called a Rufous-sided Towhee (now split into two species, the Eastern and Spotted towhees). I was hooked.

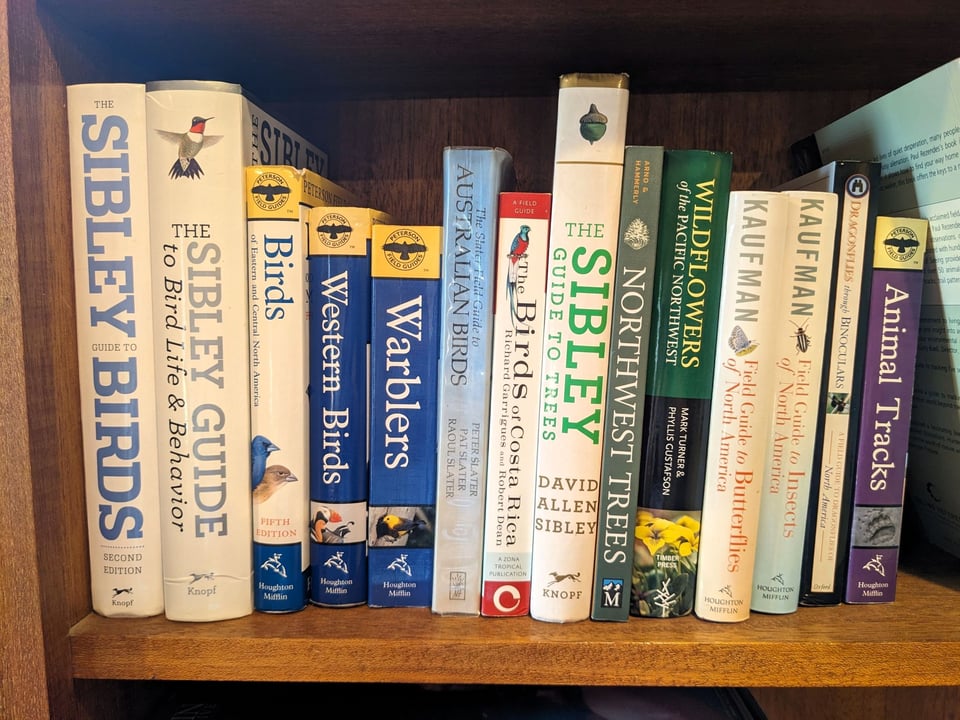

In college, I was introduced first to the Peterson guides, then the Sibley guides, and eventually added field guides to the birds of Costa Rica and Australia to my collection when I had the opportunity to travel to those places. Over time I acquired guides to butterflies, dragonflies, trees, wildflowers, and animal tracks as well. For a while — especially when I was working on my master’s degree in environmental education, living on a beautiful wilderness property in the woods of northern Wisconsin — they were all heavily used. Today, though, they mostly just look nice on my bookshelf.

I want to try to change this. Truly I remain a huge fan of old-fashioned paper books (I have never owned a Kindle or other e-reader device and never particularly want to). Yes, it’s not practical to carry my whole library of field guides on a lengthy hike, but I could start bringing along a couple of them, some of the time, and make a point of slowing down and trying to learn a little more about the life around me in real time. Okay, maybe not the bird books — I know the local birds well enough that I don’t need to consult a reference much, and when I do, I turn to the Merlin app — but, at least, the plant and insect books.

I started last month by carrying along my book on wildflowers of the Pacific Northwest when we went on a short family hike in the Umatilla National Forest. It was dry, the flush of spring wildflowers long past, but ocean spray and mock orange were still in bloom and we managed to successfully use the book to determine that the weedy yellow flowers along the path were St. John’s wort.

This hot, smoky summer can’t last forever, and maybe this fall will be my season of field guides. How often do you still carry a field guide in book form when you head out to spend time in nature?

Words About Birds

This year’s checklist supplement is out! For anyone not in the know, the American Ornithological Society maintains the official checklist of North American birds, and every year they issue an update based on the latest taxonomic research. The big news this year is the lumping of Hoary and Common Redpolls into one species. This has been coming for a long time; way back in 2017 I wrote a piece for Living Bird magazine about new advances in bird genomics in which I mentioned research showing that Hoary and Common Redpolls aren’t genetically distinct.

Earlier this year I wrote a story for Hakai Magazine about some research offering new insights into the life of the long-extinct Great Auk, and now there’s a new piece of Great Auk research out: Some folks in UK came up with new estimates of the mass of both adult Great Auks and their eggs. They argue that the body mass of Great Auks has been overestimated in the past, which has some implications for how this flightless bird would have propelled itself underwater.

Continuing with the extinct birds theme, a group of Smithsonian researchers have now analyzed DNA extracted from almost 50 Bachman’s Warbler specimens preserved in museums, representing birds from across the species’ range. This mysterious species was last reliably sighted in the 1960s, and the results of this study support the idea that its extinction was the result of a rapid decline following widespread habitat destruction.

Besides extinct birds, another fascination of mine is chickadee cognition. Some new research from the UK suggests that Blue Tits and Great Tits, European relatives of chickadees, are capable of what’s called “episodic memory” — they can consciously recall the details of specific events from their pasts. Unsurprisingly, they use this ability to remember their experiences with finding food in specific places and act accordingly.

Finally, just for fun: Enjoy some photos of really awkward-looking molting birds, courtesy of the Audubon Society. Birds typically molt and replace all of their feathers at least once a year, though the details vary a lot from species to species. For migratory birds in North America, this typically happens after they’re done breeding and before they head south. Birds that are in the middle of this process can look a little… unfortunate.

Book Recommendation of the Month

Halcyon Journey: In Search of the Belted Kingfisher by Marina Richie. This is a really lovely book by a woman who spent several years monitoring a kingfisher nest site near her home in Missoula, Montana. It’s packed with beautiful nature writing and lots of fascinating information about kingfishers, and in addition to helping me realize I’ve taken these amazing birds for granted, it also made me want to cultivate more time for my own close observations of nature where I live. Highly recommend!

Bonus: Check out my review of Kenn Kaufman’s new book, The Birds that Audubon Missed, for the Times Literary Supplement! Being asked to review this book for The London Times was a huge honor.

Upcoming Events + Miscellany

I was on an episode of the Atlas Obscura Podcast talking about the Pfeilstorch, the stork shot in Germany in 1822 with an African spear through its neck, which appears in my book!

I do also have some events coming up this fall and winter, both virtual and in person in California and Oregon — stay tuned.

-

How I learned birds: Every night, I'd read a few pages from whatever field guide held my attention at the time. I literally read field guides. I keep one in the car, but I've never actually carried one with me in the field.

Add a comment: