Bird of Passage: July 2024

Have you been enjoying this newsletter? I’d really love to grow my subscriber base, so please consider forwarding it to a friend who you think would like it too!

As I write this, I’ve just returned from this summer’s big adventure with my family, a ten-day road trip to the San Juan Islands and North Cascades National Park. Last year’s big adventure was partially scuttled when my kid came down with conjunctivitis, so this was the first time we’d been tent camping in two years. Taking a six-year-old camping, it turns out, is much different from taking a four-year-old camping.

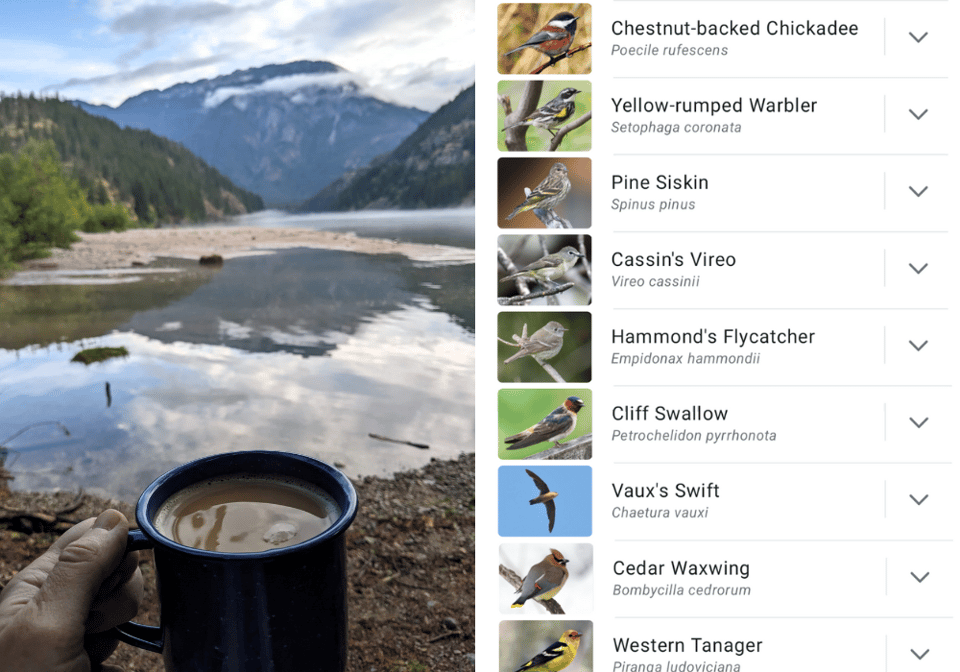

For one thing, he’s way more interested in nature now than he was two years ago. He declared our campsite on the shore of Diablo Lake to be “paradise” and said he never wanted to leave. He was thrilled when a Bald Eagle landed on the lakeshore one evening, and listened intently as I pointed out how the local Chestnut-backed Chickadees were different from the Black-capped Chickadees we see at home. He’s even getting really into plant ID; I bought a guide to the trees of the Northwest at a visitor center, and he surprised me by teaching himself how to use the identification key at the beginning of the book.

Even before this trip, my son had declared that he wanted to spend his life “helping Earth,” and regularly made signs with messages like “Stop Destroying Habitat” that he’d ask me to post in our front window. I swear I haven’t pushed any of this on him, though clearly he’s absorbed a lot of these ideas by being around me and hearing me talk about my own interests. Am I delighted by my budding naturalist? Yes. But sometimes it gives me pause.

A lifetime ago in 2019, I wrote an essay for High Country News about the first time we took him camping. “By encouraging him to cultivate [a connection to nature],” I wrote, “am I only setting him up for a painful future? He’ll live to see the unfolding climate crisis diminish our planet’s living beauty in ways that will be permanent and painful. I’m afraid that by teaching him to love streams full of salmon and woods full of songbirds, I’m betraying him, dooming him to a bitter, grieving adulthood when the streams are empty and the woods are silent.”

But to love something or someone is, pretty much by definition, to make ourselves vulnerable to the possibility of pain if we lose that something or someone. And the last thing I want is to protect my son from pain by teaching him not to love. So we walk in the woods, we talk about how to tell a sword fern from a maidenhair fern and a chickadee from a junco, and I hope that when he grows up, he isn’t too angry with me when he fully realizes the state of the world he’s going to inherit.

Words About Birds

Wanted: Information on 126 “lost” birds. The American Bird Conservancy, BirdLife International, and the nonprofit Re:wild worked together to assemble this list of species that have not been observed in the wild in at least a decade but that have not (yet) been formally declared extinct. Three North American birds, the Eskimo Curlew, Bachman’s Warbler, and Ivory-billed Woodpecker, are included on the list. (Side note: all three are probably already extinct.) The researchers behind the project hope it will spur more people to come forward with sightings of the listed species and ultimately spur conservation efforts.

Wildfire season has definitely started here in the Northwest, and some new research has shed a bit of new light on how wildfire smoke affects birds. Bird banders in the San Francisco area captured fewer birds during periods of “acute” smoke (heavy wildfire smoke over a few days) but more birds during summers with “chronic” smoke (a high number of smoky days across the whole season), suggesting that birds left the area when it was extra smoky but also just generally moved around more during chronically smoky summers. Worryingly, birds experiencing chronic smoke exposure also tended to lose wight over the course of a season.

I enjoyed this story from the Audubon Society on efforts to reduce the use of rat poison in cities. The rodenticides used today don’t kill rats instantly, and hawks and owls that catch and eat rats that have ingested the poison can be severely affected by the toxins used; Flaco, the famous escaped Eurasian Eagle-Owl that roamed New York City for a year, was likely killed by rodenticides. Cities, states, and conservation groups around the country are working to curb the use of these poisons and promote other (potentially more effective!) means of controlling rat populations in their place.

Birds have weird respiratory systems (at least, by mammal standards) in which air passes through a series of air sacs in a one-directional loop as they breathe. Scientists are still making new discoveries about this air sac system—and apparently, air sacs that extend into the wings of some birds actually help them fly! As I understand it, in bird species that soar, air sacs between the wing muscles can inflate to help lengthen and strengthen crucial parts of their wing anatomy and make soaring easier. (Birds that don’t soar don’t have these air sacs.) Birds’ adaptations for flight will never cease to amaze me!

Finally, just for fun: Apparently a bird with the delightful name of Newton’s thunder bird, which resembled a flightless, six-foot-tall goose, lumbered through Australia’s wetlands in search of fruit and leaves 50,000 years ago. The first fossils of this bird were unearthed in 1913, but more recent findings have filled in a lot of details about what it looked like and how it lived. Its closest living relatives today are the equally delightfully-named screamers, a trio of odd South American birds that look like a cross between a goose and a chicken.

Book Recommendation of the Month

The Last of Its Kind by Gísli Pálsson. Reading this book on our trip probably contributed to the heavy thoughts above. It details the experiences of two English naturalists who traveled to Iceland in 1858 hoping to study Great Auks, only to discover that hunters had apparently already killed every last one of them. It was the first time anyone had realized that humans could cause a species to become extinct, and one of the men, Alfred Newton, went on to become an early advocate for bird conservation.

Upcoming Events + Miscellany

I’ll be at the joint conference of the Association of Field Ornithologists, Society of Canadian Ornithologists, and Wilson Ornithological Society in Peoria, Illinois, from July 29 to August 1—not speaking, just helping out (I do some part-time work for the WOS) and attending talks. Please say hi if you happen to be there!

-

I've recently started subscribing to your newsletter and thoroughly enjoy it. Thank you!

I was touched by the July edition and your concerns about immersing your son in a natural world that he will likely see severely diminished over his lifetime. While I'm 62 now, let me offer a perspective from my inner little boy (who is alive and well). I, too, have seen wild places I've loved as a child transform from natural Edens to wreckage. The only thing that would make me sadder would be not having known them in their natural state. In my opinion, your son will be eternally grateful to you for sharing your natural world with him, no matter how ephemeral it is, and he'll be a richer person for it. This is just one man's (and father's) opinion, but keep doing what you're doing, mom!

With respect, Jim Lechner.

Add a comment: