Semiotics of Self-Starvation

News from the Front 22.06.25

Inventing Anorexia

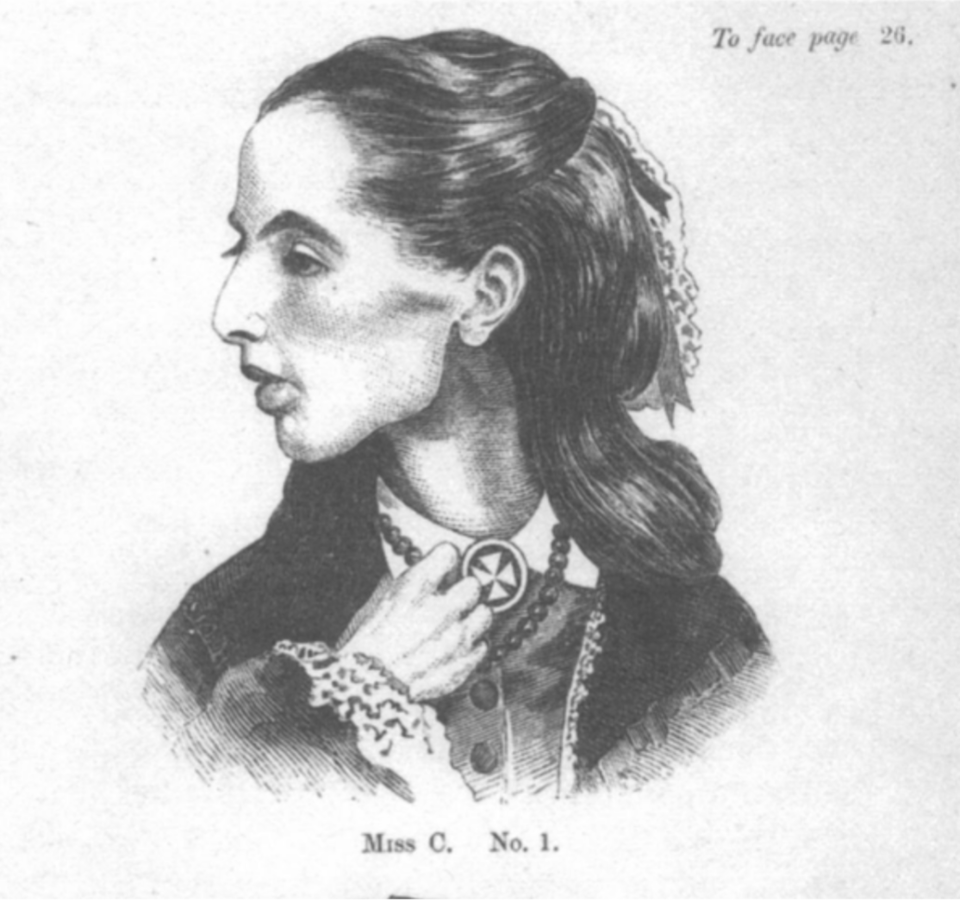

In 1873, the British physician William Withey Gull and the French neuropsychiatrist Ernest-Charles Lasègue both independently published early descriptions of what is now known as anorexia nervosa. Neither defined the disorder in terms of body image or fear of weight gain, though both physicians noted that patients seemed unbothered by their apparent emaciation. Instead, Gull emphasized starvation itself as the disease—not its cause—and sought its reversal through feeding. Lasègue, more attuned to hysteria, suggested psychological distress as a motivating factor. But in both accounts, anorexia was framed through surface symptoms and observable behaviours.

This form of nosology — defining mental illness by visible signs — remains a central tenet of modern psychiatry. Unlike other branches of medicine, where a pathogen can be located and named, psychiatric diagnosis is retroactive: clinicians extrapolate invisible “disorders” from observable symptoms, then use those same symptoms to prove the disorder exists. Symptoms are catalogued, then reified into diagnoses. The disorder becomes the name we give a pattern of behaviour—a “shape to fill in lack,” as William Faulkner put it. The classification becomes circular, a tautology legitimated by institutional repetition.

Contemporary psychiatric literature often preserves this logic. As psychoanalyst Tilmann Habermas once noted, anorexia is “clearly different” from other forms of thinness, because it meets the DSM’s criteria. Yet these criteria are themselves drawn from prior examples. The category becomes self-reinforcing: a person is anorexic because they fit the definition, and the definition is affirmed by their example.

Scientific observation, even when seemingly objective, is always theory-laden: what we look for determines what we see. In psychiatry, where no thermometer or lab test confirms a diagnosis, the assumption that all self-starvers are alike may say more about our frameworks than about the patients themselves. Whether Gull’s dragnet or Habermas’s sieve, the medical category of anorexia tends to naturalize its own assumptions. For Gull, any two patients emaciated by their own hand were alike simply because he defined the individual distinguishing factors as non-essential to the nature of the disease. For Habermas, two anorexics were alike simply because he defined anorexics by their alikeness. Two tautologies facing down 120 years in the history of force-feeding.

The Disease Model

The disease model dominates contemporary research on eating disorders, especially in biological psychiatry, where the disorder is typically framed as a neurochemical malfunction rooted in genetic vulnerabilities. Within this framework, scientific inquiry often narrows to identifying molecular “risk factors” or heritable traits — serotonin transporter genes, dopamine receptor densities, polymorphisms linked to appetite regulation. These are often little more than genetic footnotes that might, with enough funding, justify another round of grant proposals.

This is more or less par for the course with any clinicians or researchers working under the “disease model” of eating disorders – the idea that the “eating disorder” is a discrete, neurobiological entity that afflicts the sufferer’s passive psyche. It’s like a metaphorical pathogen: something foreign lodges into the psyche and requires “healing” that can only occur through the intervention of a secondary, external party (a medical authority, your loving parents, Jesus). The disease model tends to be framed as a means of “reducing stigma” via portraying the disorder as something that is morally exculpated on the grounds that it was not freely chosen – something foreign has invaded the body, so the cure must be an external intervention to get it out. The real violence of this model lies in its ability to remove bodily autonomy from a patient by casting them as helpless hosts to an invading force, curable only through the domain claims of psychiatry.

Ignoring the fact that health and illness are moralised anyway, what this model cannot account for is that “disordered eating” is often an entirely rational response to continuous and overwhelming moral demands to monitor and control bodies and appetites via food intake. As with any behaviour, there are as many ways to “have an eating disorder” as there are “disordered eaters”. There are other ways to decode the behaviour beyond a pathological entity invading the brain. As such, it’s often a means of disidentifying with, or escaping marginalisation via bodily decreation.

Aliens & Anorexia

Into this thicket enters Chris Kraus’s Aliens & Anorexia, a text somewhat anomalous in the canon of eating disorder/anorexia literature. Prior to the what is known as the “biological turn” of psychiatry in the late 20th century, anorexia was primarily reduced to quasi-religious or psychoanalytic readings in which the sufferer was either cast from or bestowed with God’s grace, was the product of a pathological family dynamic, or was a simple aspirant to fashionable thinness.

But Kraus is determined to pry anorexia from the death grip of psychoanalysis or therapeutic cliché. A&A is a non-linear, vignette-driven text that asks: what is the content of the act of not-eating? Anorexia is the shape — but what is the lack it fills? Lasègue framed it as feminine pathology; Gull dismissed psychological explanations altogether. Kraus offers a third approach: a reclamation of anorexia from the “psychoanalytic girl-ghetto of poor self-esteem.” A&A functions best as an attempt to re-code anorexia politically.

Kraus draws parallels between anorexia, alien abduction, and spiritual longing. She distinguishes between those who fear alien abduction, seeing aliens as“hostile and sadistically dispassionate invaders”— and those who seek it, longing for escape from political and self-alienation. She invokes Simone Weil’s Gravity & Grace, wartime notebooks and chronicles of her “will to wait for God”, and her own film by the same name, in which a group of New Zealand “lunatics” await alien contact — a metaphor for transcending alienation.

Two central points emerge. First, the alien becomes a figure for alterity and transcendence. Self-starvation, like seeking alien contact, is not necessarily about food or even the body — it’s a gesture toward another way of being, a means of decoding social alienation and reaching for something beyond it. Anorexia, in this reading, isn’t pathology so much as an attempt to reach a non-alienated state.

Second, Kraus explores the abduction narrative as a structure of power and violation. Returning to the contingent of people who fear abduction, the alien depicted in the narrative is curious about his (“invariably, the Alien is male”) human subject’s body. He alone is the custodian of precious knowledge that he may choose to bestow upon his captive which he dispenses in cryptic, partial terms. He shares his knowledge only verbally; the sexual encounter is an auxiliary humiliation: “It’s a little bit like playing s/m, without any of the pleasure.” The alien abduction is narrativised in a five-act structure as “a shameful and terrible ordeal.” For those who fear abduction, the alien is a stand-in for a patriarchal figure.

Here, then, is the text’s thesis: the “lack” that anorexia gives shape to is the condition of alienation itself. The Alien—both literal and metaphorical—embodies the Foucauldian nexus of power and knowledge that constructs this disjunction. For Kraus, to refuse to eat is to reject the social conditions that produce alienation: the psychiatric ward, the workplace, suburban New Zealand. Anorexia, in her framing, is not merely a clinical category but a radical gesture — a de-coding of one's intolerable environment and a re-coding in search of another kind of enlightenment.

At this point we must also contend with the alien qua abductor – an alien encounter need not present an opening, it can also function as a trap. The alien, Kraus writes, “gratifies and torments… with a partial explanation.” He bestows cryptic knowledge that is never fully intelligible — another authority figure cloaked in mystery, another patriarch dispensing meaning on his own terms. He is not liberation but continuity: the same old power structure in an extraterrestrial register.

Secondly, and more interestingly, the alien-as-abductor also tells us that for Kraus, alien-ness may serve a narrative purpose even upon return to earth. The alien abduction is not itself a recovered memory, but is like one: a placeholder for unspeakable experience. The abduction is the empty scaffolding of a story that may be filled with the content one will not, or cannot, gaze upon bare. A story about aliens is a story about something that cannot be spoken.

Medical Touch

Is it any wonder, then, the archetypal alien abduction is structured like a rape? It may not be the case that every purported alien abduction survivor is sublimating a past sexual trauma, but an alien abduction narrative may be the rare site where the connection between medical touch and rape may be made explicit. The alien possesses the doctor’s dispassionate gaze and clinical curiosity about the subject’s body; he gains access to the body in a kind of haunted house, a spaceship–lab–clinic equipped with gleaming instruments meant to render the body transparent.

Most sex-ed today aimed at children today includes a unit on sexual abuse. Draw a square around your “personal zone.” Tell a trusted adult if someone tries to touch you in a way you’re not comfortable with. Read this material more closely and you will notice that these warnings are invariably caveated, perhaps most explicitly to account for the medical encounter and the parent. No one should touch you here or here without your permission, except.

Medical sexual abuse is defined out of the child’s vocabulary. Medical touch is “salubrious” by definition. If a doctor touched you and it made you uncomfortable, you were mistaken. What happened to you wasn’t what you experienced – it was something else. You are telling the wrong kind of story.

The medical encounter is considered to be of a different character to other acts of physical touch. It is not meant to be decoded with the same Rosetta stone as rape. The trick is that, in reality, most rape is not actually meant to be decoded with the same Rosetta stone as Rape, capital-R: Rape. Proper. Someone who does not consider a medical encounter definitionally capable of involving rape does not really think a parent or a priest or a baseball coach can do it, either. The trick is that Rape is often a threat, but rape is rarely a reality. It is horrible in the abstract and unthinkable in the concrete. Its mundanity is matched by its conceptual elision.

Alien(ation)

The first problem with Aliens & Anorexia is that for all Kraus’s efforts to read self-starvation as a creative act, she cannot fully escape the logic of self-abnegation. Her reading leans heavily on a religious-cum-clinical logic that jars with her broader political ambitions.

Kraus is (rightly) sharply critical of psychoanalytic and quasi-feminist accounts of anorexia, which all more or less reduce the anorexic to a narcissistic, perfectionist, white girl at odds with her parents. “It is female psychotherapists and recovering anorexics,” she writes, “who really lead the pack in nailing down the anorexic girl as a simpering solipsistic dog.” But all these frameworks — whether psychoanalytic, glandular, genetic, or biopsychosocial — share a refusal to take the anorexic’s stated desires seriously. The point is that what these explanations have in common is a general disinterest in any expressed desires of the self-starver, rendered a kind of unreachable shadow figure trapped behind the clinical construction of the anorexic. If not-eating is to be cured by medicine, it must first be translated into its terms.

“So long as anorexia is read exclusively in relation to the subject’s feelings towards her own body, it can never be conceived of as an active, ontological state.” Kraus is repelled by the cynicism she sees in contemporary food systems — food as overpriced commodity, as imperial detritus — and suggests that not-eating can be a rejection of this cynicism. Food smells like “bills and coins and plastic”, a forcible intrusion of economic alienation in what is proffered as sustenance.

“Cynicism travels through the food chain. To stop eating is to temporarily withdraw from it. Without love it is impossible to eat.”

The heart of the text lies in the suggestion that anorexia promises escape — not the escape of death but of political liberation. Anorexia is a “state of heightened consciousness” and “an active stance: the rejection of the cynicism this culture hands us through its food, the creation of an involuted body.” This is the content Kraus offers to fill the gap of the clinical entity anorexia: it is, or at least it can be, a political act. It is an effort to reject the morally intolerable, a kind of political over-coding that cannot be contained by the prescribed drumbeat of meal-snack-meal.

Yet even this formulation struggles to fully escape the allure of martyrdom. Kraus turns to the Christian-mystic philosopher Simone Weil, who also stopped eating — not out of masochism or any apparent body-hatred, but because she wanted to “really see.” Her first experiences in decreation came through factory work, and it was this political-economic alienation — instantiated in the starved bodies of Europe’s Jews, the battle scars of resistance fighters, the dispossessed the world over — that she recreated when she ceased to eat.

Kraus hovers somewhere between rejecting psychoanalytic models and reinscribing them. Her vision of anorexia as a political act is powerful, but still rooted in a politics of the body — a kind of sacred suffering in which alienation is internalized and aestheticized. Inasmuch as food is political, so too is rejecting it. But it is still a politics articulated on the terrain of the body, a politics of whittling down the wretched flesh overrun by signifiers and suffering.

The second problem with A&A follows directly from this construction. Kraus despairs to her partner: “The global food supply — Hearst Castle — postmodern architecture with all that glass mixed in cupolas and porches — Korean salad bars, forty different flavors of identically tasteless food — it’s everything you want, except now you don’t want any of it!” This contemporary nightmare of transnational commerce is contrasted, a page later, to an anecdote from a trip in Bourgogne: a farm, Kraus’s partner "speaking fast Parisian French,” an old woman offering the couple a taste of the creamy cheese she makes all by herself, and Kraus: “And this was food.”

But what exactly is the difference between Kraus’ claim and the cottagecore gastronomic fascism of any French countryside worshipping celebrity chef? If salvation lies in French handmade cheeses, one could skip Kraus’ critique and go straight to Michael Pollan. A&A seeks to transform starvation into a kind of alienation turned inside out, a spiritual hunger misread as bodily. But this framework is naïve if its political imaginary believes alienation is to be cured with artisanal cheesemaking in pastoral Europe.

Still, the idea of a psycho-politics of identification outside the self has some teeth. Lisa Downing, writing on necrophilia, describes it as a site where identification and desire blur. In 19th-century Paris, the corpses of girls in the morgue were objects of fascination—sexual, aesthetic, philosophical. Kraus’s anorexic occupies a similar space: desiring not to be desirable, but to collapse the distinction altogether. “Among people who reject the mystical state,” she writes, “the only yardstick left for measuring the will-to-decreate is sadomasochism.”

Anorexia & Gender

Gender is not incidental to Kraus’s reading of anorexia. “Because it’s mostly girls who do it, anorexia is linked irrevocably with narcissism,” she writes. The anorexic girl is presumed to suffer from a failure of femininity—too attached to appearances, too detached from reality. But Kraus asks: what if the girl’s refusal is not narcissistic, but epistemological? What if she simply refuses to be known in the ways psychiatry demands?

In this sense, anorexia may be understood as what Gayle Salamon terms a “corporeal counter-narrative”: a bodily assertion that resists legibility. Kraus’s anorexic is not just rejecting food, but rejecting the conceptual apparatuses that make her hunger illegible—diagnosis, gender norms, recovery narratives. Her refusal may be a kind of “opacity,” in Édouard Glissant’s sense: a refusal to become transparent to institutional understanding.

Psychoanalytic and feminist critiques have long grappled with the feminisation of pathology. Hysteria, melancholia, anorexia—these are categories that have historically conflated womanhood with unknowability, with bodily excess or refusal. Yet even critical engagements with anorexia often reinforce the association between feminine subjectivity and pathological embodiment. Kraus’s intervention is to ask whether this alignment might itself be a site of resistance.

Still, Kraus’s analysis struggles to escape the logic it critiques. Her invocation of Simone Weil, who starved to death at 34 in solidarity with the oppressed, risks reinscribing a theology of suffering. Weil’s anorexia is understood as political but remains tied to the body as sacrificial terrain. Kraus attempts to recode not-eating as a form of knowledge, but cannot fully detach it from the logic of self-abnegation.

Anorexia, in A&A, is a state of heightened consciousness, a politics of refusal, a metaphysics of the body. But this remains a fragile politic — vulnerable to being co-opted by the same systems it resists. As Kraus admits, the alienation of capitalist food systems cannot simply be cured with creamy cheese in rural France. To imagine that pastoral authenticity can resolve structural alienation is, at best, wishful thinking and politically naive; at worst, class romanticism.

Don’t you want to be more beautiful?

Anorexia’s relationship to beauty has never been simple. Medical photography has long documented emaciated bodies, yet the same images, in other contexts, provoke outrage or voyeuristic fascination. ‘Pro-ana’ is a fetish object for its detractors, a sewer rat prowling the underbelly of the information age: a social body instantiated into a starving teenage body and coming inside your house to steal away your chubby-cheeked babies and turn them into bratty scrawny strangers. From time to time some public health official or another will propose to run pictures of emaciated anorexics on billboards, or in educational TV shows, to warn the impressionable public against the danger of the disease.

The public, for their part, generally find such images both titillating and scandalous — or perhaps titillating because they are scandalous.

The implicit claim here is that anorexia is not just dangerous, but ugly. Indeed, the promise of most ‘eating disorder treatment centres’ remains along the lines of We will make you more beautiful. Don’t you want to be more beautiful? As one recovery testimonial puts it, “My boobs are fuller … My husband thinks I’m sexy.” This is for the same reason that before-and-afters depicting recovery can’t show fat recovered anorexics: their existence threatens the conceptual linkage between health and beauty upon which the anorexia clinician’s career rests. A girl must be thin. But she must have flesh, too — at the very least enough to reproduce. Anorexia thus describes a pathology in which “refeminizing” the emaciated body becomes synonymous with saving the patient’s life. In this framing, the physician transforms anorexia into a condition that is both caused and cured by vanity.

Kraus, in Aliens & Anorexia, also probes alienation, but with less clarity. Suffering debilitating flareups of Crohn’s disease, she develops a worsening fear of food; rummaging through a friend’s kitchen, she reads the labels not just for trigger ingredients but as the provenance documents for her next meal. She is bothered by the distances these foods have travelled, by the number of hands and machines that have touched them. The unknown here is the food; the efforts to make transparent aim at it. Food is the conduit to pain. Pain maps the contours of the body, social and individual.

In Kraus’ film Gravity & Grace, the aliens never come; instead, a curator urges an artist to distinguish “mere debris of capitalism” from something “more heartfelt.” Read: decode, but then recode. Read: food. Read: eat. Or don’t.

Part of the difficulty here is that the association between women and mysticism is not usually a very interesting one. Women’s nature is chaotic, unknowable, illogical; women have access to some occult higher knowledge: these are not new ideas. In the sixteenth century, fasting teenage girls were paraded about in European medical literature as evidence that women were medical aberrations and wonders of nature (prodiges de la nature). Andre Breton said that women (referring to Frida Kahlo) had a greater connection to surrealism because of this purported mystical connection to nature. The rhetorical construction of nature as the non-agentic terrain upon which man articulates his dominance has long been linked to analogous claims over women’s bodies.

The notion of womanhood-as-alienation is a necessary component of any epistemology of anorexia, but where A&A simultaneously traffics in the notion of womanhood-as-alien, it does little besides unify two unproductive schools of ambivalently feminist thought. A&A comes to feel like intellectual edging.

Although there is plenty to dislike in what might euphemistically be called the ‘trauma narrative,’ one upshot of the psychotherapeutic turn is that trauma is generally considered to be a kind of chronic affliction. Anorexia, on the other hand, has been thoroughly relegated to the realm of the curable, which by corollary means that if you still have it you must not be trying very hard to get rid of it. Anorexia has two accepted trajectories: death or recovery. Anorexia has no future. If you intend to live with it, you are mad and probably socially dangerous. So why bother re-coding it at all?

I’m uninterested in recovery narratives as a genre, and I don’t think starvation is intrinsically any more meaningful than non-starvation. But it’s no less meaningful, either. There is content to the act. It can be known and named; it is quite often itself a means of knowing and naming—or not-knowing and re-naming, as the case may be.

Fiona Mant is a writer based in Montreal. You can reach her at fionacmant@gmail.com

Write, pitch, submit HERE

READING LIST

▪ Aliens & Anorexia - Kraus

▪ As I Lay Dying - Faulkner

▪ Mind Fixers - Harrington

▪ Psychiatric Hegemony - Cohen

▪ Fasting Girls - Brumberg

▪ Desiring the Dead - Downing