Junkyard Mnemotechnics

Field Report 08.06.25

I was still in Korea when I thought to make it.

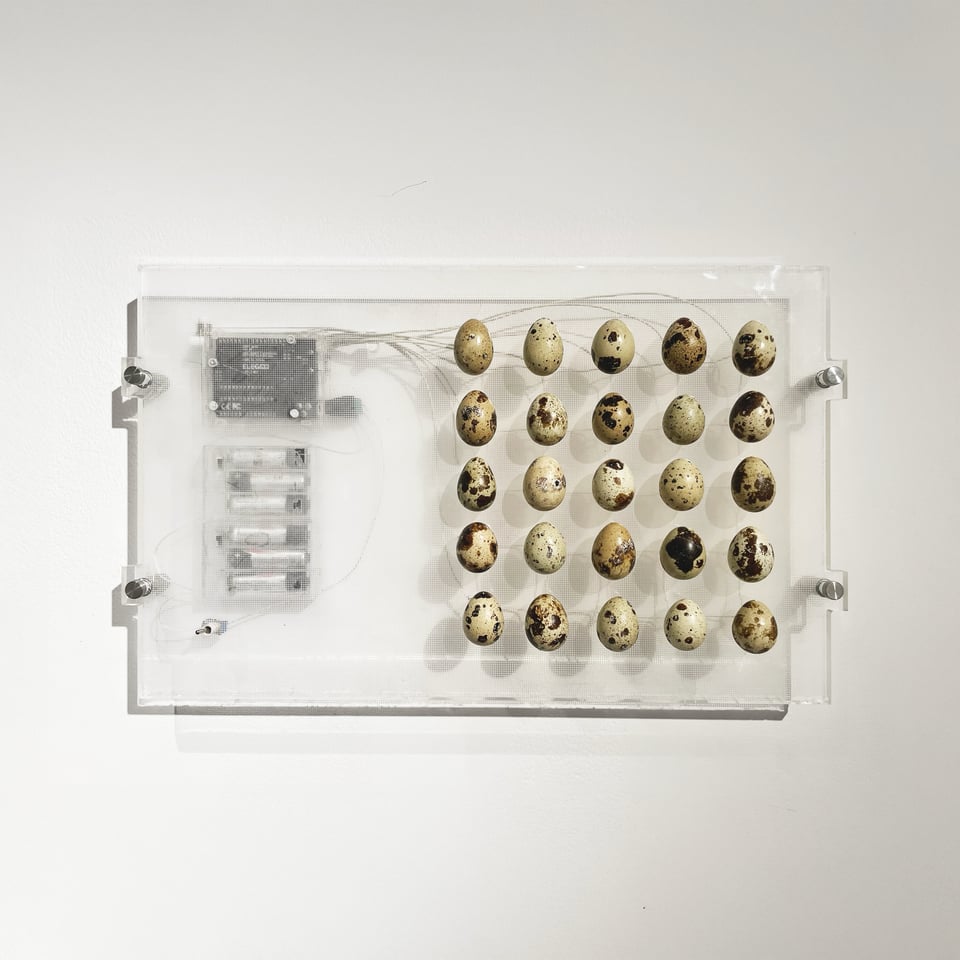

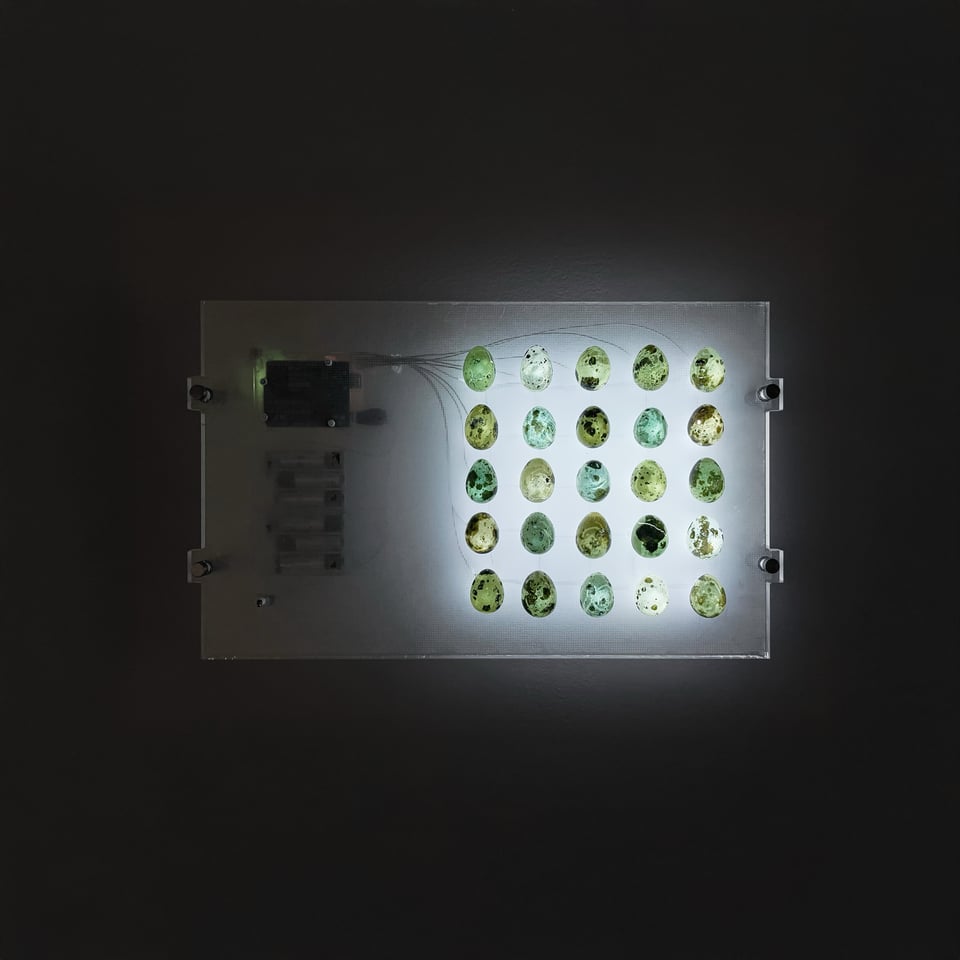

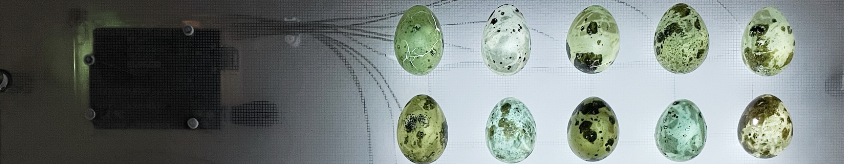

Thank You For Having Me is a light-based sculpture composed of a grid of 25 hollowed quail eggs, each housing an LED and mounted on a reclaimed plexiglass panel, salvaged from the interior of a vintage Apple computer monitor. The quail eggs are wired through an Arduino microcontroller and powered by a battery pack. There are multiple lighting modes: from a kind of uniform brightness to randomised fading/flickering.

It comes from a memory: while I was in Korea, I peeled quail eggs with a woman with whom I had trouble communicating. There was a language barrier.

It’s a container for memories then. Like butterflies pressed under glass but still buzzing, still emitting, at least artificially, electrically.

As an art-work, it calls for the appraisal of each egg not in isolation but in direct connection to a sinewy apparatus. Plugged in, or intrusively operated, cyborg-like. Body horror: the rescued computer monitor inners (ironically from Apple) string together the eggs, pulse light into them, force them into a hardware-thread of association. Like framed butterflies, Thank You For Having Me is the organic object denied decomposition.

Memory accumulates according to its own geometry. Mnemotechnics, inherited from Antiquity, is architectural. Memories aren’t dredged up from deep waters when you recollect them (despite anything Freud has written about the subject), but limbically constructed in the moment. The form of recollection dictates what exactly you recollect.

Tell me if this sounds familiar: your mind clings onto certain objects or trinkets and ascribes to them, for no particular reason, an annoying significance. Rooms remembered as organised in a certain way. Fetish objects. Have you seen a phrase or expression be run into the ground before? Ever roll a word around in your head until it turns into nothingness?

That’s not quite right though. When you repeat a word enough times it isn’t so much that the word stops making sense, but that the fragile mouth-sounds of language become sort of ridiculous. The medium overrides the message. Words become empty containers.

This is the context of my recollection. The quail eggs reference a personal experience of being invited into a loved one’s culture and home, where love was communicated wordlessly through the act of preparing and sharing food. A speculative technology more-or-less tender. It archives tenderness.

How susceptible are you to sinister intrusive thoughts? To pesky patterns that move through your memories in the way paranoia does?

When Marshall McLuhan turned east to look for androids (while anticipating the internet 30 years in advance), he hoped that the humans of the future (us) might find themselves more adaptable, more conceptually flexible about the spaces we inhabit.

The 3D visual spaces of memory bend to these associations of things with other things. Our relationships with certain objects, to each other. The internet provides the greatest possibility for contradiction - and with it our memories have become acoustic, multisensory, a memory is re-interpreted perpetually.

Interestingly, Thank You For Having Me can also be interpreted as a mirror to human ramifications upon nature. Quail eggs are made to speak, or at least made to absorb, and then shown to feel. Contaminated bodies - McLuhan, if you were wondering, is one of the largest influences on the work of David Cronenberg.

The politics of Thank You For Having Me are the politics of Mnemotechnical Machines in general. Machines that do more than conserve, that re-inject, artificially resurrect memories, that present the past. This is foreign to the west, where our histories are drawn with straight lines even when they aren’t (I’m talking about Hegel).

Find something new. Gandhi’s politics of memory was an all-encompassing permanent present, subject to constant re-interpretation. Gandhi’s envisioning of a new kind of world (the principal sympathy of the R.Y.F.F) is partisan; historical determinism is the basis for for both colonisation (industrialisation as an eventuality) and class.

The irreversible transformations that have taken place in society since modernity, especially changes in the sense of time and the nature of people’s relationships to objects, are mostly foregrounded for us in the work of east-asian scholars who face the strangest of its symptoms. Lisa Yoneyama’s attempt to wrap her head around Hiroshima, for example, is impossible, incoherent. The way she “brushes history against the grain” (Benjamin) is by hopelessly reckoning it with the present, using the present as a sort of vocabulary.

There are other fronts. Partisan guerrilla of the french-occupation Jacques Lusseyran lost his eyesight as a child:

I saw light and went on seeing it though I was blind. I said so, but for many years I think I did not say it very loud. Until I was nearly fourteen I remember calling the experience, which kept renewing itself inside me, “my secret,” and speaking of it only to my most intimate friends. I don’t know whether they believed me but they listened to me for they were friends. And what I told them had a greater value than merely being true, it had the value of being beautiful, a dream, an enchantment, almost like magic.

I could feel light rising, spreading, resting on objects, giving them form, then leaving them.

Jacques Lusseyran, 1953.

Thank You For Having Me stems from a material investigation into quail eggs as both an object of aesthetic interest and a vessel for memory. It references a place where love was communicated wordlessly through the act of preparing and sharing food. Each illuminated egg becomes a quiet container for such memories. I suggest a speculative technology that harbours hospitality.

Video below.

Kayt “Tech” Meraw is a cyberartist based in Montreal. Get in touch at techmeraw@gmail.com

Elliot Mann is a writer and researcher based in Paris. Reach him at elliot.l.mann@proton.me

Write, pitch, submit HERE

READING LIST

▪ Hiroshima Traces - Yonemaya

▪ Face aux verrous - Michaux

▪ The Global Village - McLuhan

▪ Of Grammatology - Derrida

▪ Cosmos - Gombrowicz