Who does what?

Hello, and welcome to the 29th edition of the Dispatch. Tim, Lara and I are working on the first Polycrisis essay for 2025; identifying the themes and issues we’ll be looking at this year. That process inevitably means picking which ones we hope to avoid.

The overarching questions for the year are all tied to the Trump presidency. The chaos and Knightian uncertainty coming from the US isn’t an excuse to look away. But a core focus for The Polycrisis project has been centring Global South countries, as strategically and economically powerful actors in the world, as well as moral ones. This Dispatch highlights a few of the comments at Davos this week from different European and African leaders; plus some new resources on critical minerals. Look out for our first big newsletter essay of 2025 in the next week.

- Kate

***

South Africa has its first G20 presidency this year; the first ever by an African country. Brazil is hosting the COP and BRICS. The “Financing for Development” conference takes place in June and the Pope is calling for a debt Jubilee in 2025. The actions of Europe and China will likely be as significant for “the rest” as the US. China is not stopping its manufacturing of electric vehicles, solar panels, batteries or AI – but it is also not particularly interested in ramping up concessional or grant-based financing other countries to buy its products, regardless of the fantasies of a new green Marshall Plan. What will Europe do, amid its political-economic paralysis?

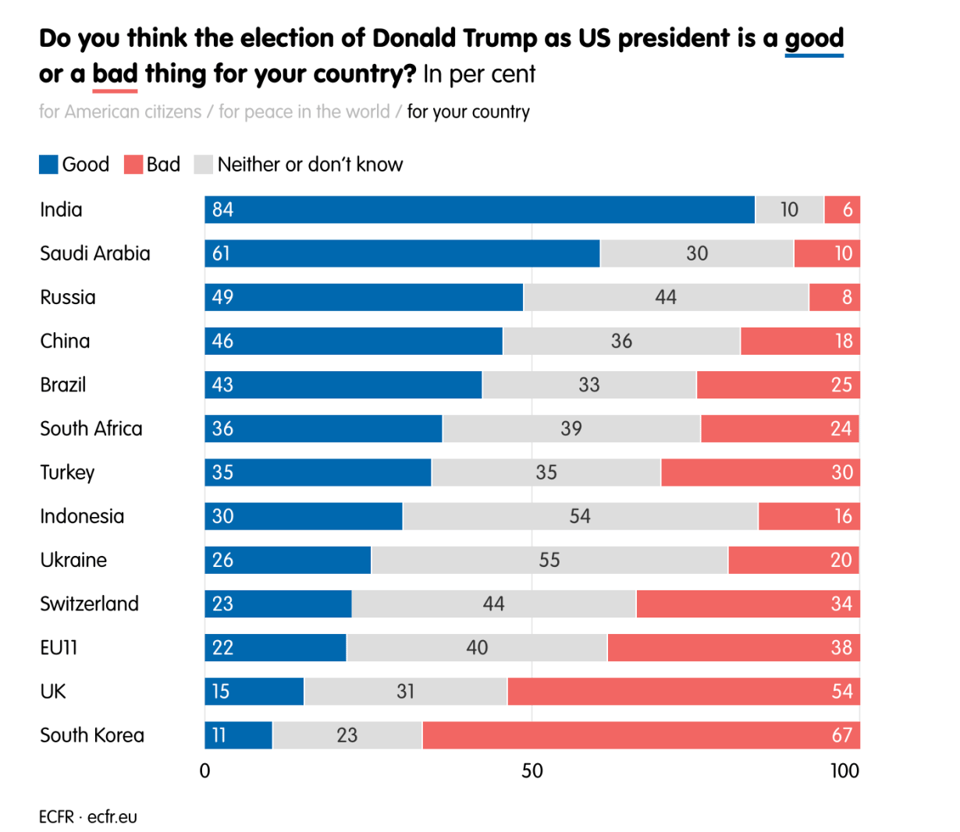

The European Council on Foreign Relations published a large international survey on perceptions of the US under Trump:

“In short, Trump’s return is lamented by America’s long-time allies but almost nobody else.”

“But the survey reveals that many in the world regard the EU as a player equal to the US and China—a strength European leaders should draw on as they enter the turbulent new presidential term.”

***

Davos taking place the same week that Trump takes office was ironic timing for the hopes and the hypocrisies of globalisation as the US is frantically trying to dismantle the world order it largely created (at least, the parts it hadn’t already dismantled over administrations from both parties).

Ursula von der Leyen spoke ruefully of the hubris of 25 years ago: “25 years ago, the era of hyper-globalisation was nearing its peak… some of us even thought it was the ‘end of history’.” Then she warned against Chinese overcapacity and talked of being “ready to negotiate” with the US. Her solutions to the fragmentation and difficulties besetting Europe were just as pedestrian and predictable: deregulation and capital market union.

Friedrich Merz, the likely next German chancellor, spoke against immigration in a Davos set piece interview, referring to “500,000 within the last four years who came to Germany without any control” under family reunification rules. “This has to be stopped immediately to get rid of this big problem with migration.”

He spoke against Bürgergeld, the German welfare scheme. For more Hartz reforms deregulating labour markets. For closer ties with Italy’s far-right prime minister and great replacement adherent, Giorgia Meloni: “I don’t understand the reservations towards her. She is very pro-European, very clear on positions towards Ukraine and Russia, and very pro the EU rules based order. Why don’t we talk with her, more than we did in the past?”

This left Spanish PM Pedro Sánchez to gesture in the direction of something dynamic and non-reactionary: that Europe should be much more vigilant against the dangers of social media. Arguing that social media affects democracy and is a kind of public good, he called for user identification requirements; algorithm transparency; and accountability for tech CEOs whose platforms foster disinformation.

South African president Cyril Ramaphosa’s speech centred on the theme of cooperation and collaboration, as the first African host of the G20 this year. He spoke of climate change but anchored it firmly in the question of equity. His speech focused on concrete international financing channels such as making Special Drawing Rights available to developing countries, and better disaster financing, and new international financial sources such as taxation. G20 framework on green industrial minerals and critical minerals - "particularly close to the source of extraction”.

“We will use this G20 to champion the use of critical minerals – through a programme of green industrialisation – as an engine for growth and development in Africa and the rest of the Global South.”

***

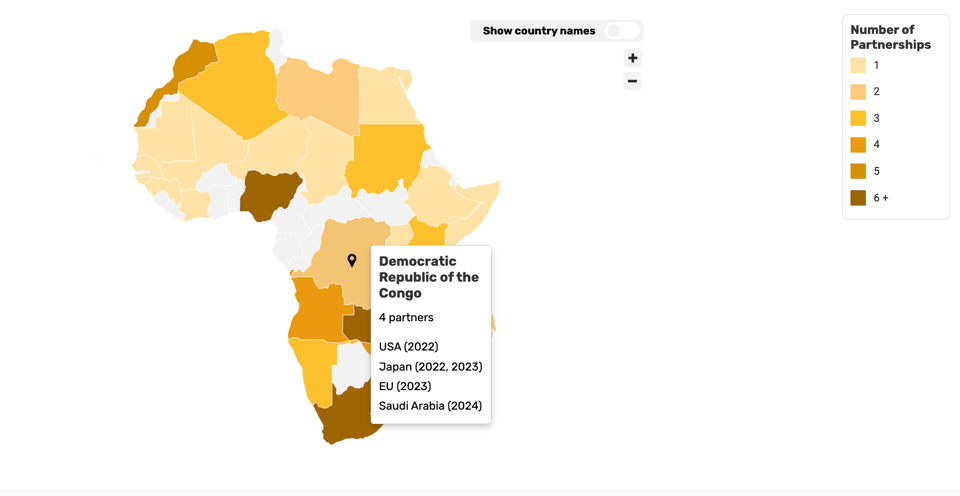

That will be a big undertaking. Two new resources have been published in the past week attempting to catalogue what is known about international critical minerals projects – but the gaps are just as notable as what they show. Opacity is rife; a big African Policy Research Institute project mapping African countries’ agreements outside of the continent stresses that it’s a very incomplete picture.

Technology transfer will be vital if African countries are to benefit from critical minerals resources as hoped. The only countries with significant agreements in African countries that were mentioned for tech transfer are decidedly not western: Saudi Arabia, Japan, and Indonesia. A vast repository of Global South country policies and stakeholders created by Columbia University doesn’t paint a much more optimistic picture; few examples of tech transfer appear (although it mentions that the UK, too, has included it in some agreements). It suggests that the African Group of 44 proposal on technology transfer be adopted by the WTO, as the TRIPS regime is inadequate, and that international organizations make tech transfer a condition of financing.

That is all for this very, very long week. We are skipping the Dispatch next week in order to focus on the essay - please make sure you are subscribed here.

*Under the international trade regime, the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), to which all Phase 2 countries are parties, aims to protect and enforce intellectual property rights as a way to promote technological innovation, dissemination, and transfer. While developing country governments could, in theory, use TRIPS flexibilities such as compulsory licensing to expand access to green technologies such as those relevant to decarbonising critical minerals value chains,65 it is unclear whether the limited tools provided under the Agreement would be most effective for that purpose.66 WTO reform and further negotiations on issues of relevance to developing countries, such as those proposed by the African Group of 44 countries to the WTO Working Group on Trade and Transfer of Technology (WGTTT), may be necessary to develop appropriate mechanisms for technology transfers under the trade regime.67

Add a comment: