UK development strategy; Hurricane Beryl; Jamaica

Hello! It is the TENTH edition of our dark-mode weekly email.

First, a reminder that our book club for this month is “Planetary Mine” by Martin Aberdola. You can join the Discord server where meetups are being arranged in various cities, and also nominate your preferred times for the zoom call on July 29, 30th or 31st.

We've had emails about our Kenya IMF debt crisis pieces (both the dispatch and the longer Phenomenal World essay) from people in many countries. It hit a nerve given the Great Global Austerity shift and dollar debt crisis which goes so under-reported in transatlantic media. Some of the feedback is further down. And thanks to Beirut-based Sifr magazine for translating it into Arabic! We couldn’t agree with their masthead more: "economic journalism as a political act contrary to the mainstream and its vulgar economics, an additional voice with the exploited against the exploiter".

This week, in the wake of the elections, we wonder whether the new UK government will make a decent effort on aid, debt and development, or whether diplomacy and defense matters will be tied to development. Then we look more closely at Jamaica – which we touched on last week for its relative success in implementing a strict IMF program – but also austerity, and catastrophe bonds and other “parametric insurance” instruments that are meant to protect vulnerable countries from devastation wrought by storms like Hurricane Beryl.

Next week we’re taking a break, because most of Europe is and neither of us are there but it’s frustating and we’re jealous. Back with edition #11 round late July.

Global boiling, again

With hot oceans, we are very worried about the Atlantic hurricane season. Thirty named storms are predicted (with a plus/minus of 5, depending on how El Niño–Southern Oscillation goes). Hurricane Beryl damaged the Grenadines and Jamaica, killing at least 10 people; parts of Mexico, and it is now bringing deadly storm surges and tornadoes to Texas and Louisiana. Cyclone season in the Atlantic begins on June 1, but a Category 5 event has never been recorded so early in the year. This hurricane was unique, and was intensified by climate change, according to the Climameter science consortium. Meanwhile, intense heat waves are affecting many parts of Europe, the Americas, the Middle East, and South Asia (Wikipedia has a list of 2024 heat waves but we’re pretty sure it’s not exhaustive).

The new UK government

Now that one G7 country is led by a party which was key to effecting a G7 debt jubilee in the mid-2000s, what can we expect it to do about the debt crisis now affecting over 60 developing countries? 2024 is the costliest debt service payment year this century..

Alan Beattie beat us to some of the things we were planning to write about this, asking, “can Labour restore the big aid budgets and the credibility in international development they had under Blair and Brown?” High on the list for many in the development sector is restoring the allocation of overseas development aid (ODA) to 0.7 percent of GNI after the Conservatives cut it to 0.5 percent, but Beattie suggests that credible development aid is more worthwhile than simply targeting a quantum, which will just lead the government to cynically relabelling of other finance flows.

David Lammy is now the UK foreign secretary, but only late last year his predecessor David Cameron set out a new strategy for the FCDO in a 155-page white paper. The Cameron white paper advocates for rapid responses when emergencies hit, as this is more evidently impactful than traditional foreign aid.

Will Lammy build on that approach? In a speech in May he strongly advocated for diplomacy, development and defence to “work together in unison”; disappointing to those who would like to see a UK development stance free of more pragmatic matters (Alan Beattie discusses the implications of re-merging). The new government’s initial response to Hurricane Beryl was to send half a million pounds worth of tents and buckets for people in Grenada and St Vincent and the Grenadines.

On climate diplomacy and climate finance; Carbon Brief has assembled a to-do list for the new government – and it’s rather big. Meeting its own climate finance target, helping the fraught negotiations on the NCQG (the successor target to the international $100 billion per year goal); and aligning its ETS with Europe’s are just a few.

What Jamaica tells us about the IMF

We mentioned Jamaica in both the Dispatch and the full PW-Polycrisis essay on Kenya. Something we found interesting about the Kenya story was how the negotiations between the IMF and the government of the country played out. A plan that includes replacing a chunk of 6%-ish debt for 10%-ish debt (as Kenya did this year) and harsh austerity, instead of seeking some debt restructuring, seems terrible.

But perhaps the most interesting point of the Brookings paper we flagged should have been that only a handful of countries have ever successfully implemented massive debt-to-GDP cuts without social and political upheaval. The story of Jamaica’s efforts to build multi-stakeholder consensus over several decades sounds – at least, from far away in time and geography – inspiring. The fact that all this political and social hard work was then used to implement a dramatic austerity program? Not so great.

A reader, the economist Ndongo Sylla, pointed this out to us, and referred to a powerful letter that Peter Doyle wrote to the FT earlier this year after a column riffing on the same research:

That striking deviation from best practice resulted in annual average GDP growth per capita for Jamaica over that period of just 0.3 per cent, compared with 4 per cent for its best peers. That implies that had Jamaica applied the same policy discipline it took to sustain 7 per cent primary surpluses over 30 years to following the policy frameworks of its best peers — including primary deficits of 0.3 per cent — its GDP per capita would have been of the order of three times higher than it was in 2019.

[...]

So while one cannot but be awestruck at the sustained commitment displayed by Jamaican governments over three decades to meet their creditors’ debt repayment demands, the resultant stagnation means that this is emphatically not an example for the world to emulate, or for Jamaica to continue — as required under its latest IMF programme.

Resilient returns versus resilient countries

What the Jamaican government did get from the international community, in addition to a punishing austerity program that may have left its economy a third the size of its potential, is a form of hurricane insurance courtesy of “catastrophe bonds” organized by the World Bank. A new $150m cat bond was issued with the Bank’s assistance just a few months ago. In theory, these bonds pay out the insured party – in this case, Jamaica – when the specified catastrophe occurs.

So Jamaica should be able to address its millions of dollars worth of damage to crops and infrastructure from Hurricane Beryl, right? Not from the cat bond – because the air pressure from Hurricane Beryl reportedly didn’t reach the threshold level specified in the contract.

These sorts of bonds are usually based on parametric insurance, which means they pay out in the event of an event that meets the specifications in the bond contract – it is not related to the actual damage that occurs. Parametric insurance has been characterised as an innovation that will help climate-vulnerable nations like Jamaica – see this from the UN, for example, or this Sustainable Markets Initiative taskforce. Parametric insurance products are also a key element of the Global Shield initiative, a partnership between northern and southern governments and the re-insurance industry – particularly popular with Germany. So it’s unsurprising the World Bank, which has been an enthusiastic supporter of complex financial innovations like pandemic bonds, is supporting such instruments.

For countries, the argument is that parametric means payouts will be fast. The flipside is that they may pay nothing, even when devastating damages and losses from the insured event are suffered – or the “triggers” (which can be defined over several hundred pages). And worse, the intricacy of the triggers mans that payouts can still be too slow. A devastating drought in Malawi in 2017, for example, only paid out a fraction of the total possible amount, nine months after the drought was declared and when 6.5 people were going hungry due to the drought.

The possibility that a cat bond or other parametric insurance instrument pays out nothing …. when the insured event causes damage is a feature, not a bug, of parametric insurance.

A report published by African Policy Research notes that insurance in general for develop countries’ resilience to climate change-driven damage is problematic and “best suited to operate as complementary measures within a wider suite of measures that include a well-resourced LDF (ideally funded from contributions based on historic emissions), sovereign debt relief and more effective social protection systems.

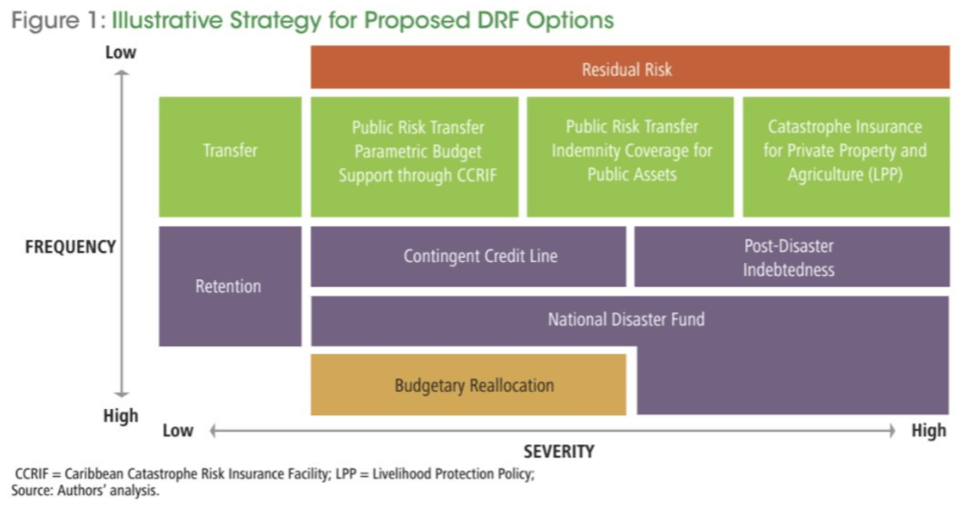

In the absence of most of those provisions, for most countries, even expensive and limited insurance might be appealing. Jamaica’s government in fact has multiple sovereign insurance arrangements, as this schematic from the finance minister, via Artemis.bm, shows:

The vagaries of insurance arrangements can be almost existential for small climate-vulnerable countries, but not for the investors who take the other side of the cat bond gamble. If a hurricane, for example, does meet the parametric triggers then they can lose some or all of their initial investment; but for most, such bonds are only a tiny part of their portfolio. If no event meets the payout triggers, they can get returns as high as 20 percent!

The bonds are popular for being “perfectly uncorrelated to other financial market factors, Schroer’s thoughts; although with compounding climate crises that seems over-confident.

Did you read this far? Did you like it? Please feel free to email us Tim (asahay@gmail.com) and Kate (kate@katemackenzie.net)

Add a comment: