The climate finance COP

Hello and welcome to the 23rd edition of the Dispatch. Tim is heading off to Brazil for the G20 and a holiday, and the excellent Lara Merling is going to be a regular contributor for the next little while. We met Lara via her old gig at Boston University’s Global Development Policy Center, but it takes a full bio to account for the breadth and depth of her expertise. Most recently she wrote the brilliant “Greenwashing” Structural Adjustment for Phenomenal World, about the IMF.

This week we tackle the extremely fraught topic of climate finance; about which much has been written over the years, and very little resolved. Plus a bit of Tim’s new report and some links on the US election. As usual, please contact us here: Kate and Tim or the group address. Or find us on Bluesky

- Kate

This year’s UN climate summit is about finance. It might seem hard to believe that any of the COPs have not been entirely about finance – the whole premise of the negotiations, surely, is who pays? But agendas have also been filled by matters such as reporting on emissions reduction measures, target-setting procedures, and multilateral carbon offset markets.

The COP taking place now in Baku, Azerbaijan, is the one where countries are expected to agree on a new target for how much money needs to flow from developed to developing countries, to enable them to cut emissions and adapt. The current goal is $100 billion per year between 2020 and 2025, which was enshrined in the Paris Agreement in 2015. Developed countries missed this target in 2020 and 2021 but claim to have met it in 2022.

“Climate finance” was defined as separate and additional to the 0.7% gross national income target for official development assistance (ODA) that wealthy countries have agreed to at the OECD (that promise, too, is broken).

Source: Natural Resources Defense Council

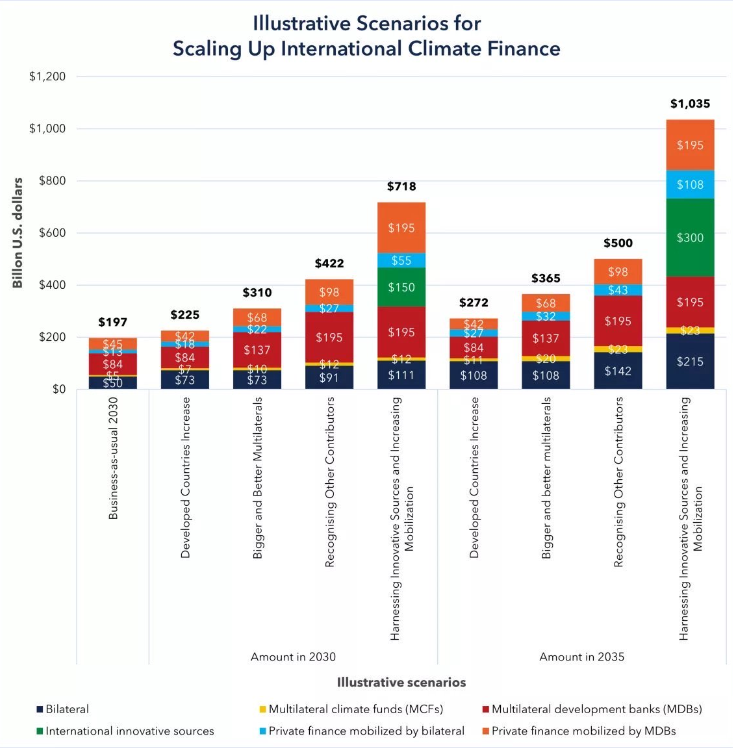

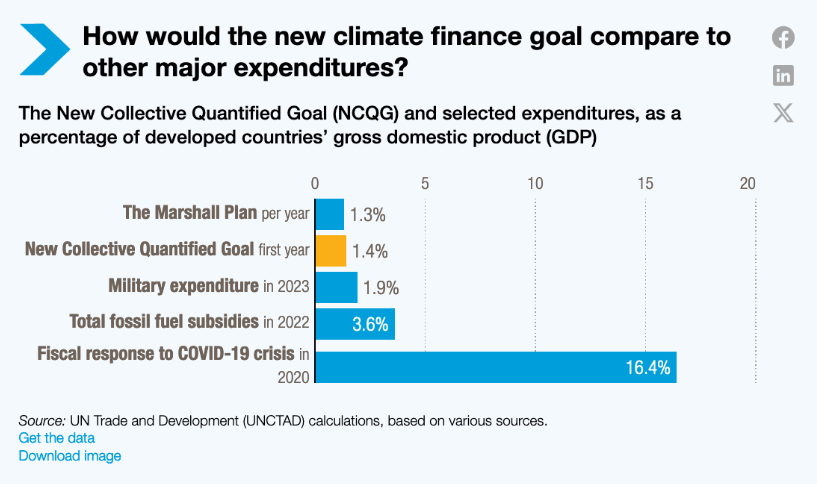

UNCTAD estimates that to live up to the commitments made in the Paris Agreement, developing countries require around $1.1 trillion in support in 2025, with that amount gradually rising to $1.8 trillion by 2030. This is in line with the submissions from developing countries in terms of the size of a new target and is not far from the Independent High-Level Expert Group’s estimate of $1.3 trillion.

These numbers might seem high, but it is comparable as a share of GDP to the Marshall Plan, and lower than what developed countries spend on their militaries or fossil fuel subsidies:

Reaching an agreement on the size of the goal is the first step – agreeing on what can be counted toward the goal, and how the finance is delivered, is just as important. This includes clarifications on whether market rate loans, or any type of loans, can really be claimed as financial support, as well as what type of projects are really climate investments.

In the UNFCCC agreements, the type or modality of finance has not been specified. This matters a lot: grants, or concessional loans? Multilateral development banks? As Oxfam pointed out, most of what is counted toward 2022’s climate finance total came in the form of debt, estimating the “true value” of public, grant-based climate finance as more like $28 billion that year.

Meeting the climate finance target and ensuring developing countries can afford their climate and development plans means commitments made at the COP must also be reflected in reforms of the international financial architecture, where developing countries are currently trapped in cycles of debt and underinvestment, and are estimated to be spending over $400 billion servicing debts to foreign creditors in 2024 alone.

We’ve all argued for several years that climate finance has to be considered in the context of global financial architecture to be meaningful. That’s a view that began to become mainstream around 2022, as climate disasters grew, fossil fuel prices shot up, and a wave of debt distress took hold in the majority of developing countries. The IMF and the World Bank began to take a more active interest in the COPs, and in turn, by 2022 the COP cover decision text referenced multilateral banks and international financial institutions (such as the IMF). It was not too soon: the diffuse world of climate finance couldn’t address the squeeze on balance of payments, and it was increasingly obvious that climate change – both mitigation and adaptation – couldn’t be separated from development. The proliferation of climate-related tweaks and initiatives in the international financial architecture – outside of the UNFCCC – are too numerous to list here, but they include: a new IMF facility; outside efforts to rechannel the Special Drawing Rights that were issued by the IMF in 2021; (less helpfully!) the IMF’s climate strategy; climate-debt swaps of dubious benefit; climate-debt clauses.

But it’s reform at the MDBs that have become the focus of much of the attempts to address climate finance at the scale that is required. A thinktank, Recourse, shows in this new report that multilateral development banks have some questionable practices when it comes to what they are including in their climate portfolios; airports and gas infrastructure projects among them.

This gets to another conflict within climate finance: adaptation versus mitigation. Because mitigation measures can be projects that lead to revenue flows (renewable energy facilities, for example) they can fit somewhat easily into debt-financing or more “innovative” financing methods such as securitizing MDB loans. The “additionality” qualifier these days is mostly to protect against wealthy countries from double-counting their development and climate finance contributions but, conversely, an early feature of the finance track in the UNFCCC negotiations was suspicion from wealthy countries that climate finance was merely a cover story for more development finance. As Gareth Bryant and Sophie Weber write in their 2023 book, Climate Finance, opposition to “adaptation finance” was strong:

“As an arena for climate governance, adaptation was resisted or sidelined through the early stages of the UNFCCC process (Schipper 2006). This started to change throughout the mid-2000s, with recognition that future climate impacts were inevitable and some were beginning to be felt; this shift emerged with advocacy about vulnerability in developing countries, including by the Alliance of Small Island States. Nonetheless, the first steps towards funding adaptation activities were taken in 1995, when the Global Environment Facility (GEF), the financial mechanism for the UNFCCC housed within the World Bank, was drawn upon to fund adaptation planning.”

This led to a concerted effort to get developed countries to commit to a minimum adaptation component – which had some success in 2022.

Who pays and who receives?

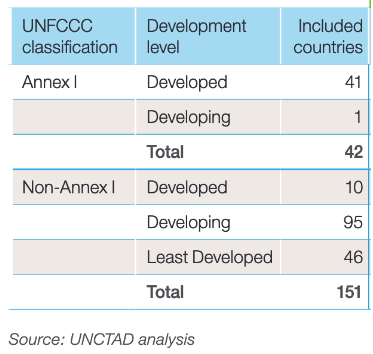

The main point of contention in the finance negotiations is which countries should be a part of the contributor pool, and which countries should be eligible to receive support. Wealthy countries argue that existing classifications don’t accurately reflect countries’ current position – not so subtly hinting at China. The G77 and China argue this issue has already been settled by Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, which specifies that “developed” countries are responsible for providing financial support for “developing” countries.

Within the UNFCCC, countries are divided into two main categories: Annex I, comprising industrialized countries considered responsible for the bulk of historical emissions, and non-Annex I. These are based on the UN designations of development status. In what’s also an indictment of the dominant economic model of the last three decades – only 10 countries have climbed up the income ladder since 1992:

Those 10 that have ascended are Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Israel, South Korea, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, San Marino, and Serbia – none of which are close to the controversies around who should be included in the contributor or the recipient pool. Even China, where a lot has changed since 1992, is still classified as a developing country by the UN. While it could be argued that the classification isn’t accurate, the COP is not a venue where that designation can be debated.

Rising emissions in China and other large emerging economies, along with the significant per capita emissions and robust financial status of some Gulf States, are critical points. Aware of the optics, Chinese officials have highlighted their financial support for climate efforts in developing countries, and Gulf Cooperation Council climate finance funds are proliferating, to more scepticism. Wealthy nations can seize on these shifts as illustrating why the pool of contributing countries should be enlarged. Without leading by example and delivering on their own obligations, though, the optics for wealthy countries looking to hold others accountable are not great.

The “IRA-in-reverse” global climate moment

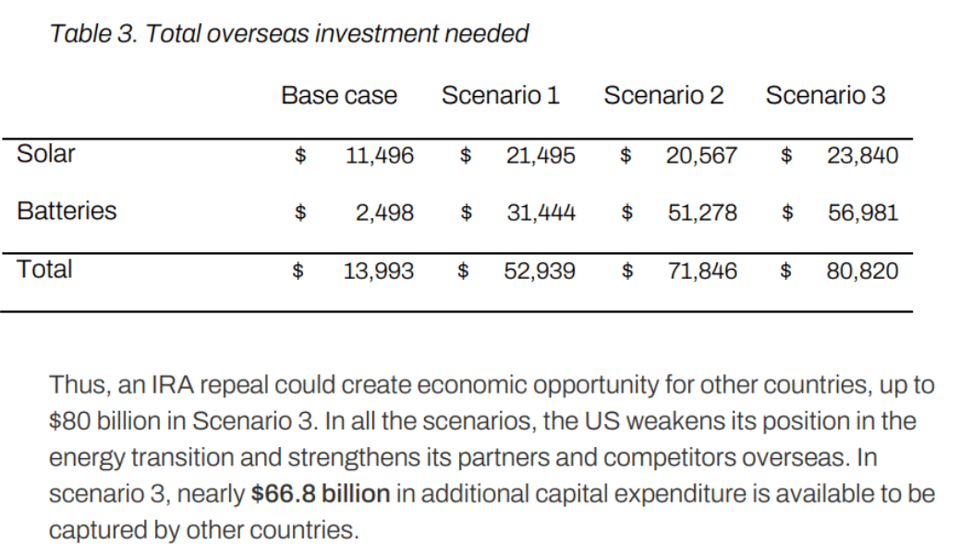

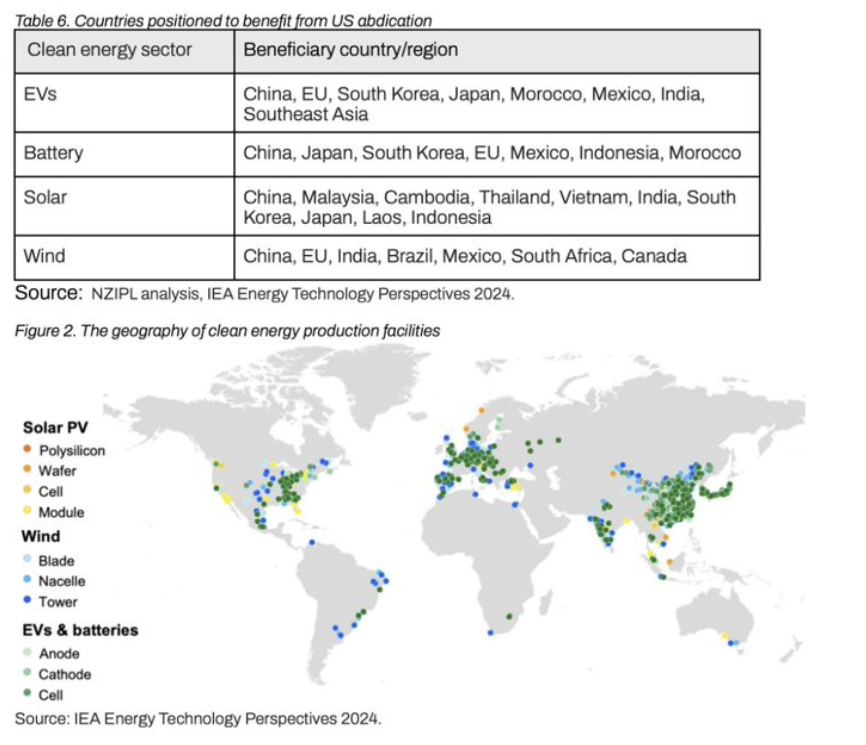

A Trumpist repeal of the climate portions of IRA, BIL, CHIPS would harm the US. Think of it as the opposite of the global reaction after IRA passed: creating tens of billions of dollars in opportunities for other countries while the US itself, inevitably, remains a source of demand for clean goods. Tim and Bentley Allan, his co-director at the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab at Johns Hopkins, analysed three different scenarios of rollbacks of the IRA. They find repeals of incentives hurts production of ‘make in America’ green goods while their demand by Americans continues to outstrip supply. They write: “At this point, the climate transition is inevitable, and we're merely going to empower Europe, China, Japan, South Korea, and the other countries that have put their economies all-in on the energy transition. A Trump Presidency with Republican-controlled House will only delay and create problems for the energy transition. It can't prevent it, and therefore it can only harm the American public in both the short term and in the long term.”

What we are reading; Aftershocks of the US election

US Exit Right by Gabe Winant; possibly the most acerbic take of all:

At each juncture, the Democrats have attempted restoration: to manage the crisis, carry out the bailout, stitch things back together, and try to get back to normal… And it is against this politics of containment that Trump’s obscenity comes to feel like a liberation for so many.

Democrats Need to Clean House Now, Before They Screw Up Again by Kat Abughazaleh

When you choose to be ineffective, it’s no wonder many stayed home, while others who voted for Biden defected to Trump. And to not have run on a platform of real change—and, for that matter, in direct opposition of the current, wildly unpopular president—is shameful.

After Trump, let’s fight neofascism together by Arun Kundnani

“Neo-fascism’s electoral successes are grounded organically in both the recent domination and failure of neoliberal culture.

“The Left, on the other hand, has to start from scratch. Decades of neoliberalism have buried the collective values that animated the mass movements of a century ago.

Thanks for reading! That is all from us this week - we will return next week.

Add a comment: