Sputnik or steampunk

And other metaphors for China-US competition in 2025.

Welcome to the 49th Dispatch, after a short hiatus (we missed last week). Our BRICS essay came out yesterday, just in time for the bloc’s summit in Brasilia. Most anglosphere media coverage has focused on disunity within the group (which is often the case) and the absence of Xi Jinping (which is unprecedented, and remains a mystery at pixel time).

The focus on disunity is understandable. BRICS has a catchy name and some attention-grabbing aspirations relating to currency, but it isn’t anything like a security alliance or trade bloc, and members’ views differ on critical questions (that way it’s not so different to other coalitions).

We really like hearing from readers. You can email us (Tim, Kate) and follow us on Bluesky (Kate, Tim, Polycrisis account) and join our Discord. And please, forward this to anyone you think might enjoy it!

BRICS

Our argument is that BRICS is important in terms of the remaking of the material world, more than finance or diplomacy:

“While the West sees BRICS as an anti-western bloc quixotically dedollarizing, the bloc is now held together less by repulsion to an old order than by attraction to the remaking of the material basis of a new sovereignty in a new era of globalization.”

Carnegie Endowment published a compendium of views from an expert in each of the existing, new and aspiring member countries. “Technology transfer” or variations on that theme were mentioned by almost every respondent. A lot of this is about China’s IP and know-how - eg UAE using its oil wealth to develop renewable technology and transition mineral processing. But there are also collaborations on transition resources and markets, such as Brazil and India on bio aviation fuel.

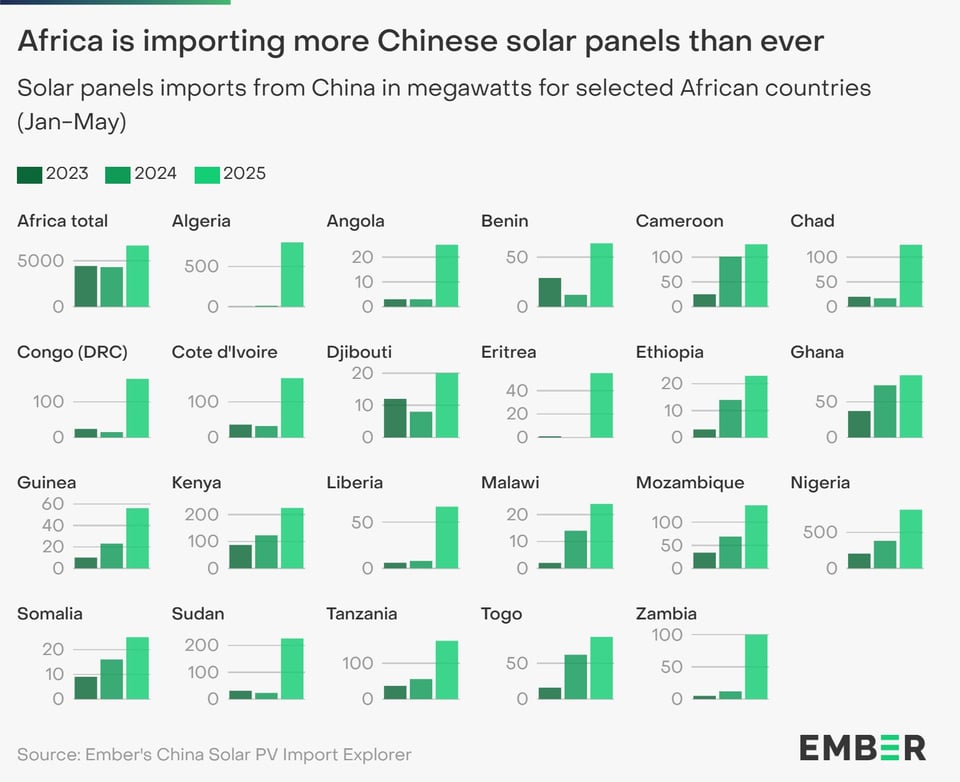

Then there are the straight-up imports of cheap solar panels:

Sputnik moments

In writing about BRICS, what we kept coming back to was this: China’s various high-tech accomplishments, many of which date back to the Made in China 2025 industrial policy launched a decade ago, are emerging at the same time as the US has become an unpredictable, unreliable actor in world affairs. And the US is now cutting back public science and medical research funding, driving out international students and scholars, and abandoning what progress it has made in clean energy technology.

China’s high tech industries, meanwhile, have benefited from decades of industrial policy, including the Made in China 2025 effort. One of the most interesting things I read in writing this piece was a Chinafile article asking half a dozen China experts, from China and the US, what they thought would be the next “Sputnik moment”: biotechnology; an Nvidia chip rival; cheap and appealing EVs; nuclear reactors. The picture of entire ecosystems of new technologies was compelling - like sub-sections of Kyle Chan’s “overlapping ecosystems”.

Adam Tooze calls it the “second China shock” but we thought “reverse China shock” could describe it better. From the essay:

If the first was when China was incorporated into Western and East Asian supply chains, the second runs in reverse: the West, particularly in Europe and particularly around EVs, is looking to be incorporated into theirs. For the first time in two centuries, the West is no longer the leader in future technology, but the follower. It’s in this context that American allies in Europe and East Asia are now beginning to break away from an aggressively transactional US that is trailing in lead technologies.

Our essay nominated three “Sputnik moments” (derived from a conversation with Helen Thompson in May) —- Deepseek; the successful retrieval of material from the dark side of the moon, and the more diffuse EV moment.

However, it is not a Sputnik moment if the US looks the other way. Alan Beattie wrote that the Trump administration is squandering the lead it once had. The US was the home of the lithium ion phosphate battery used in many EVs — a product that it’s now ceding to China by reversing tax credits for the vehicles.

The Sputnik satellite fired up US enthusiasm for scientific advance: 12 years later, an American walked on the moon. If Trump and the current Congress had been in charge back then, they would presumably have decided to let the Soviets do space exploration and concentrated instead on building jumbo jets and big cars with fins.

This image of a US clinging to clunky, outdated (and polluting) machinery is pervasive. Liam Denning described US energy policy as a commitment to Steampunk:

This offshoot of science fiction imagines a retro-futurist world where industrial steam power remains the cutting edge; think Jules Verne, zeppelins and Babbage machines. The description is all the more apt because the GOP appears to imagine that 19th-century energy sources will underpin US dominance of 21st century fields like artificial intelligence. Far from fostering leadership, it will hamstring America’s efforts.

As that excerpt highlights, it’s incoherent —- the opposite of the ecosystems outlined by Kyle Chan. In the Chinafile piece mentioned above, Lizzie C. Lee talks about small modular nuclear reactors being deployed in China specifically to power AI. And China’s Grid Energy Research Institute says a record 500GW of renewables will be installed this year to meet growing demands of AI. Meanwhile in the US, aluminium smelters are in a losing battle with tech companies for electrical power supply contracts.

It’s not about the dollar system

The BRICS-dollar-replacement narrative is an endless source of “well, actually” opportunities for anyone with a bit of interest in the financial system. It’s true that BRICS countries do want to reduce their proportion of dollar denominated trade for both sovereignty and financial reasons. But simply replacing the US currency’s international role is unrealistic; the bricolage system has evolved with the dollar. Digital currencies are a different story: stablecoins tied to the US currency could increase dollar dominance, but China been building stablecoin capacity in Hong Kong, along with its own digital yuan.

…………………………….

Other things to read on de-dollarization:

Also in Phenomenal World, Karthik Sankaran has an excellent essay on how the current administration’s seemingly contradictory plans for the dollar, and how they might drive a more multi-polar economy.

Our 2024 essay, New World Order?, looks at the swaps, IMF facilities and safety nets that make up the international financial system.

A 2022 monograph by Tufts researchers Zongyuan Zoe Liu and Mihaela Papa called “Can the BRICS de-dollarize?” identifies two different pathways - “reform” and “go-it-alone”.

We shall return, next week!

Add a comment: